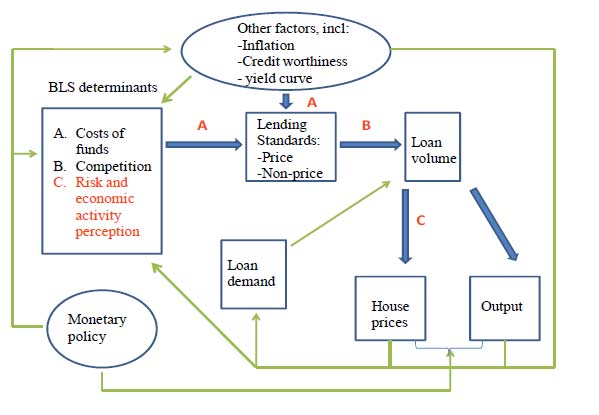

Falling interest rates imposed on the Australian economy by the RBA have, so far at least, not been successful in driving the desired economic outcomes. Inflation is very low, alongside wage growth, household debt is sky-high, the dollar remains high, business investment is subdued, yet asset prices are inflated. Why might this be?

The phenomenon of national boom and bust cycles within countries is well known. The boom phase is associated with rising asset prices, easier access to finance, loose risk settings, and increased leverage. This may last for many years. But at some time, the worm will turn, leading to changed risk perceptions, a fall (often sudden) in asset prices and deleverage.

However, recent analysis has shown than national financial cycles are partly subsumed by global financial cycles. These cycles are driven by the policy settings of large countries, like the USA and China, in the context of global financial markets. We see the longer for lower interest rate settings leading to global players searching for yield. As a result, the price of risk falls. These forces collide with the local economies. So will central banks in smaller, open economies be able to make local monetary adjustments successfully when monetary policy transmission mechanism is affected by global risk factors and that these factors may move in the opposite direction to conventional monetary policy moves?

However, recent analysis has shown than national financial cycles are partly subsumed by global financial cycles. These cycles are driven by the policy settings of large countries, like the USA and China, in the context of global financial markets. We see the longer for lower interest rate settings leading to global players searching for yield. As a result, the price of risk falls. These forces collide with the local economies. So will central banks in smaller, open economies be able to make local monetary adjustments successfully when monetary policy transmission mechanism is affected by global risk factors and that these factors may move in the opposite direction to conventional monetary policy moves?

A timely Bank of Canada working paper “The Global Financial Cycle, Monetary Policies and Macroprudential Regulations in Small, Open Economies“, looks at this issue and draws some important conclusions.

Specifically, for small open economies, like Canada, and Australia, while there are large costs associated with financial crises, they suggest that the central banks’ leaning against the effects of the global financial cycle would typically be too costly. Central banks cannot rely on a combination of conventional and unconventional monetary policies alone to offset the effects of financial crises. Some form of micro- and macroprudential policies are also required to lower both the likelihood and severity of a crisis.

Here is their non-technical summary:

This paper offers an overview of the implications of the global financial cycle for conventional and unconventional monetary policies and macroprudential policy in small, open economies (SOEs) such as Canada. We start by reviewing the recent evidence on financial cycles. An important new finding is that national financial cycles may have been partly subsumed into a global financial cycle. The global financial cycle is driven, in part, by monetary policy decisions in the United States. Low-for-long U.S. policy rates cause global financial intermediaries to search for yield, which in turn leads to a decline in the cross-section of international risk premia. Risk premia form an important part of conventional and unconventional monetary policy transmission mechanisms in both large and small economies.

Next, we review the available policy actions that could be undertaken by SOE central banks and regulatory authorities to limit the effects of the global financial cycle. We show that conventional monetary policy actions in both large and small economies are affected by movements in global risk premia. The paper also examines the effectiveness of unconventional monetary policies originating in SOEs that are not coordinated with those in large countries.

If unconventional policies undertaken during financial crises are not completely effective in restoring output or inflation to their target levels, the question then arises as to whether central banks can use more aggressive conventional monetary actions to lean against the buildup of debt associated with the boom phase of the global financial cycle. We highlight new work that evaluates the potential for central banks to lean against the winds of the global financial cycle. This new work shows that the cost of leaning is quite high relative to the benefits of lowering the likelihood of either entering a house price correction episode or of triggering a new financial crisis.

We then assess to what extent macroprudential policy tools could be an alternative to curb increased risk-taking behaviour during the boom phase of the cycle. In large economies, a number of macroprudential policies are designed to break the chain that links asset allocation decisions by financial intermediaries with the resultant declines in risk premia. Such policies are likely to be less effective in SOEs, as global premia will likely not change in the face of portfolio switches by small institutions or by a relatively small number of households. At the end of the paper, we use our framework to provide suggestions for macroprudential policy reforms to improve the effectiveness of the current toolkit in SOEs.

They conclude:

New research illustrates the importance of accounting for the impact of the global financial cycle on both conventional and unconventional monetary policies as well as on macroprudential policies in small, open economies. The global financial cycle, driven in part by U.S. monetary policy decisions, affects the asset and liability allocation decisions of financial intermediaries and investors worldwide. Changes in these allocations cause time variation in global risk premia, which affects the domestic monetary policy transmission mechanism in SOEs. It also affects the conduct of macroprudential policies.

While the global financial cycle complicates the implementation of conventional and unconventional monetary policies, it does not imply that these policies are ineffective. The research does point out that the monetary policy transmission mechanism is affected by global risk factors and that these factors may move in the opposite direction to conventional monetary policy moves. This suggests that monetary policy may have to be more aggressive in the future, given the future lower level of the neutral rate. Unconventional policies may become much more conventional.

The buildup of debt during the boom phase of the global financial cycle raises the likelihood of a subsequent financial crisis. New research shows that the central banks can lean against the growth of the debt stock by keeping policy rates higher than warranted by current conditions. This is effective in lowering the likelihood of either a large house price correction or of a financial crisis over the long run. However, these effects are not large enough to overcome the negative consequences for borrowers who face a higher cost of debt. Thus the basic message of Svensson remains: In general, monetary policy should clean, not lean.

However, the costs of risk-taking behaviour induced by accommodative monetary policy should not be discussed in isolation from its benefits. The easing of monetary policy was needed to foster macroeconomic stability prior to and during the crisis, and premature removal of monetary stimulus to alleviate risk-taking behaviour could fall short of having a significant impact on the financial imbalance, hinder the recovery that it helped generate, or, under low capital or liquidity levels, even lead to a credit crunch. In addition, low interest rates may have direct positive effects on financial stability. For example, higher profit margins and lower delinquency and default rates may decrease risk aversion and raise prices of legacy assets or collateral assets, leading to healthier balance sheet.

Thus, central banks cannot rely on a combination of conventional and unconventional monetary policies alone to offset the effects of financial crises. Clearly, some form of micro- and macroprudential policies are also required to lower both the likelihood and severity of a crisis. The research surrounding the global financial cycle suggests that macroprudential policies in SOEs need to be coordinated carefully across borders and within the country itself. While capital controls may potentially diminish the impact of global financial cycles, the additional cost that they impose is likely too large. Discussions on potential use of capital controls should also be mindful of the limited evidence of their effectiveness, the absence of adequate cost-benefit analysis in the literature, their potential spillovers (i.e., the potential to divert capital flows to other countries), as well as the limited data available to assess their impact on developed-country capital markets.

Note: Bank of Canada staff working papers provide a forum for staff to publish work-in-progress research independently from the Bank’s Governing Council. This research may support or challenge prevailing policy orthodoxy. Therefore, the views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and may differ from official Bank of Canada views. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank.

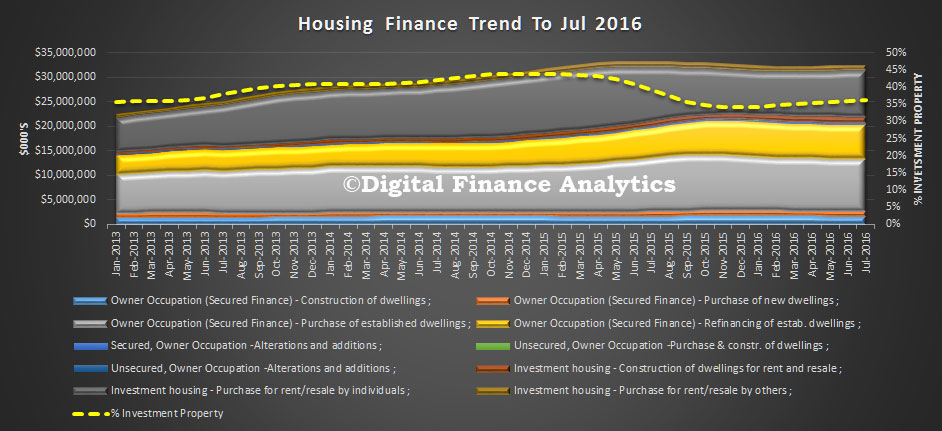

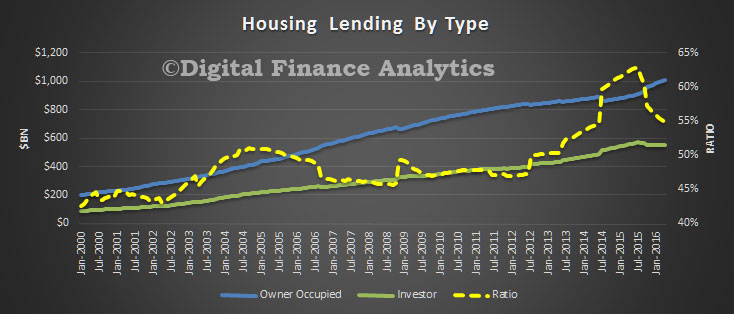

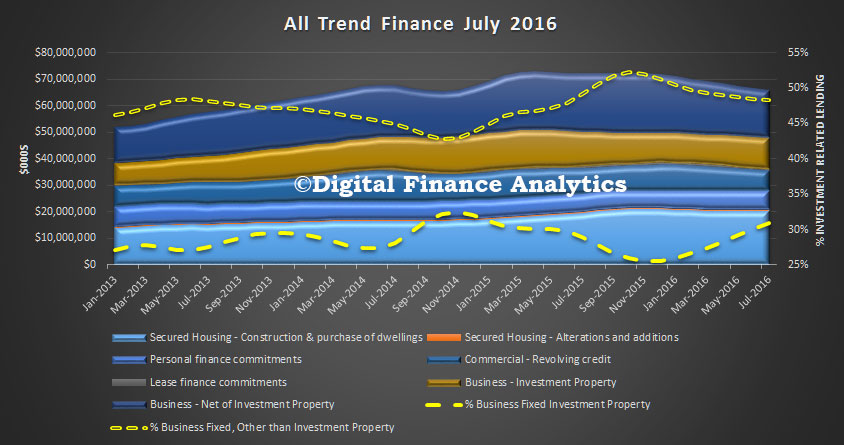

Finally, for completeness, here is the housing data, once again showing the ongoing rise in the proportion of investment housing lending, up 1.1% or $127m on last month, and up from 35.9% to 36.1% of total flows.

Finally, for completeness, here is the housing data, once again showing the ongoing rise in the proportion of investment housing lending, up 1.1% or $127m on last month, and up from 35.9% to 36.1% of total flows.