We review the latest data from the RBA, APRA and ABS, plus higher mortgage delinquencies and new bill to clamp down on cash transactions. A lot to talk about!

Full show on the war on cash: https://youtu.be/770M2s6ZD8Y

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

We review the latest data from the RBA, APRA and ABS, plus higher mortgage delinquencies and new bill to clamp down on cash transactions. A lot to talk about!

Full show on the war on cash: https://youtu.be/770M2s6ZD8Y

We review the latest data from the RBA, APRA and ABS, plus higher mortgage delinquencies and the new bill to clamp down on cash transactions. A lot to talk about!

Full show on the war on cash: https://youtu.be/770M2s6ZD8Y

The number of Westpac mortgage customers impacted by an error in 2017 has blown out to 40,000 customers despite initial estimates of less than half that number, via InvestorDaily.

In 2017, Westpac announced that an expected 13,000 owner-occupier customers had been charged excess interest due to what they called a manual “mortgage processing error”.

The bank has now disclosed that the full number of consumers impacted by this error has been pushed up to 40,000, with the total remediation cost increasing with it.

The processing error impacted those with interest-only loans and happened due to the bank not switching the mortgage holders to principal and interest mortgages at the end of their interest-only period.

Due to the error, Westpac consumers paid extra interest as their principal did not decrease, despite the interest-only term expiring.

Westpac’s general manager of home ownership, Will Ranken, said the bank identified the error back in 2017 outlining the issue, following which the bank conducted a full review.

“Customers who were not ahead of repayments paid excess interest when their home loan did not switch to principal and interest at the correct time had to be remediated.

“Many of these customers have already been refunded, and we are working hard to complete this remediation program,” he said.

Mr Rankin said the bank was refunding the excess interest already paid and providing a lump sum to make up for future interest payments on the principal loan amount that had not been reduced.

“Our approach is to ensure no customer pays more interest over the original loan term as a result of this error,” he said.

The manual process that resulted in the error has now been switched over to an automated one, confirmed Mr Rankin.

“We apologise to customers impacted and want to assure our customers that we have since introduced an automated switching process to prevent this error occurring again,” he said.

The bank did not confirm when all customers would be fully remediated but did confirm that affected customers do not need to do anything to get the refund.

We look at today’s APRA announcement and their changes to mortgage lending practice guidelines. What are the implications?

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has announced that it will proceed with proposed changes to its guidance on the serviceability assessments that authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) perform on residential mortgage applications.

In a letter to ADIs issued today, APRA confirmed its updated guidance on residential mortgage lending will no longer expect them to assess home loan applications using a minimum interest rate of at least 7 per cent. Common industry practice has been to use a rate of 7.25 per cent.

Instead, ADIs will be able to review and set their own minimum interest rate floor for use in serviceability assessments and utilise a revised interest rate buffer of at least 2.5 per cent over the loan’s interest rate.

APRA received 26 submissions after commencing a consultation in May on proposed amendments to Prudential Practice Guide APG 223 Residential Mortgage Lending (APG 223). The majority of submissions supported the direction of APRA’s proposals, although some respondents requested that APRA provide new or additional guidance on how floor rates should be set and applied.

Having considered the submissions, Chair Wayne Byres said APRA believes its amendments are appropriately calibrated.

In the prevailing environment, a serviceability floor of more than seven per cent is higher than necessary for ADIs to maintain sound lending standards. Additionally, the widespread use of differential pricing for different types of loans has challenged the merit of a uniform interest rate floor across all mortgage products,” Mr Byres said.

“However, with many risk factors remaining in place, such as high household debt, and subdued income growth, it is important that ADIs actively consider their portfolio mix and risk appetite in setting their own serviceability floors. Furthermore, they should regularly review these to ensure their approach to loan serviceability remains appropriate.”

APRA originally introduced the serviceability guidance in December 2014 as part of a package of measures designed to reinforce residential lending standards.

Mr Byres said: “The changes being finalised today are not intended to signal any lessening in the importance APRA places on the maintenance of sound lending standards. This updated guidance provides ADIs with greater flexibility to set their own serviceability floors, while maintaining a measure of prudence through the application of an appropriate buffer that reflects the inherent uncertainty in credit assessments.”

The new guidance takes effect immediately.

Copies of the letter and the updated APG 223 are available on the APRA website here.

The RBA’s Jonathan Kearns, Head of Financial Stability Department spoke to the Property Council. He said that the share of banks’ housing loans in arrears is now back around the level reached in 2010, the highest it has been for many years. But arrears are still well below the level reached in the early 1990s recession. But… we are NOT in recession….??? He concludes that housing arrears have risen but by no means to a level that poses a risk to financial stability. But as he says, mortgage arrears can be associated with significant personal trauma for borrowers.

I want to address an important issue for the property industry – the rising rate of housing loan arrears (Graph 1). Why is it that an increasing share of housing borrowers are behind in their mortgage repayments? Mortgage arrears can be associated with significant personal trauma for borrowers. They also point to a rising risk to the financial system as housing loans are 40 per cent of banks’ assets. If the value of the property backing the loan exceeds the value of the loan then arrears won’t have a big impact on banks’ profits or capital. But with falling housing prices the potential for banks to experience losses increases. So, on several fronts, this is an important issue.

There are many reasons why borrowers fall into arrears, almost all of which involve a fall in income or rise in expenses – or both. Some borrowers experience personal misfortune, such as ill health or a relationship breakdown, which is unrelated to economic conditions or the quality of their loan. And even in good times, some people become unemployed. So there will always be some borrowers who fall into arrears.

However, it is weak economic conditions that drive cyclical upswings in arrears. In particular, borrowers can struggle to make their payments if their income falls. Weak conditions in housing markets make it hard for borrowers to get out of arrears by selling their property. Conversely, large increases in interest rates, say to slow an overheating economy, can also contribute to rising arrears.

Banks’ lending standards also play a role in arrears. And it is important to note that economic conditions and lending standards interact. Poorer quality loans might continue to perform well in good economic conditions, and only fall into arrears with an economic downturn. In contrast, good quality loans will be more resilient in a downturn.

Because of the interaction between the various drivers of arrears, we often cannot point to a single cause of rising arrears. Today I want to discuss the ways in which economic conditions and lending standards are pushing arrears rates higher.

But first, it’s worth pausing to compare some benchmarks for the level of arrears. The share of banks’ housing loans in arrears is now back around the level reached in 2010, the highest it has been for many years. But arrears are still well below the level reached in the early 1990s recession.[1]

While the increase in arrears and its level is notable, the rate of arrears in Australia is still relatively low internationally, and in an absolute sense. The available data indicate that arrears are lower in Australia than in many other advanced economies (Graph 2). Indeed, another way to look at the arrears rate in Australia is to note that over 99 per cent of housing loans are on, or ahead of, schedule. Making loans involves risk, and banks are used to managing this risk. If the arrears rate was persistently very low, that would suggest that lenders were being too cautious in lending. In that world, some people who could almost certainly repay a loan would struggle to get one.

So what drives arrears? Income is a major determinant of whether borrowers can meet their repayments. Strong employment growth for a number of years now has seen the unemployment rate decline. On the surface, this makes it surprising that rates of arrears have been rising. But the relationship between unemployment, income and arrears isn’t straightforward.

One factor at play is that, while the unemployment rate has declined nationally, this hasn’t been the case everywhere. What we can see across Australia is there is a clear pattern of more loans going into arrears in locations where the unemployment rate is higher (Graph 3). Notably the unemployment rate has increased and income growth slowed in Western Australia and parts of Queensland with the end of the mining boom. These areas have seen larger increases in arrears. In Western Australia the arrears rate is now around double the rate in the rest of the country. But the flow of loans into arrears in these regions is more than would be suggested by the unemployment rate alone.

Indeed, rising unemployment in some areas can’t be the whole story. As I said, the national unemployment rate has declined in recent years. So, when it comes to arrears, falling unemployment in some regions has not compensated for rising unemployment in others. One explanation is that it can matter who becomes unemployed and who gains a job. People aged in their thirties and forties are more likely to have a mortgage, particularly if they have good employment prospects. So, if more of them become unemployed, arrears rates will rise. Conversely, if it is older or younger workers who get a job, but don’t have a mortgage, or second income earners in households already comfortably making their repayments, this won’t lead to a decline in arrears rates.

The length of unemployment can also influence arrears. Around two-thirds of borrowers have accumulated buffers of prepayments of their mortgage, and some others have other assets outside of their property. Households with financial buffers can withstand some period of unemployment, but if that extends too long and depletes their savings, they risk falling into arrears.

There are several other reasons why focusing on unemployment doesn’t tell the full story. It isn’t that all borrowers either receive income or don’t. Often borrowers may lose some of their income, say because of reduced work hours, a smaller bonus or because tenants move out of their investment property. When they don’t have a large income or savings buffer, even small income falls or an unexpected increase in expenditure can put borrowers into arrears. Indeed in Western Australia where arrears have increased most, rental property vacancy rates have been high, reducing the income of landlords.

The rate of growth of income can play a role too. When nominal income is rising strongly, over time, mortgage payments take up a declining share of a borrower’s income. As their mortgage ages and their income rises, borrowers are better placed to withstand a fall in their income or rise in expenses. Over the past five years, nominal income growth has been around half its longer-run average.[2] So, rising income hasn’t been able to compensate for other factors that might cause households to struggle to make their mortgage repayments.

Another recent feature of arrears is that, on average, mortgages are staying in arrears for longer. There are several possible explanations for this. Mortgages can leave arrears because the lender takes possession of the property and sells it. However, the number of repossessed mortgaged properties is very small and if anything has risen slightly, so this can’t explain longer loan arrears.

Alternatively, borrowers can leave arrears by selling their property and repaying the loan.[3] In a strong housing market it is easy for borrowers struggling to make repayments, or already in arrears, to sell their property. In a strong housing market, it doesn’t take long to sell a property at an attractive price. The owner is also likely to have had several years of price growth, increasing their equity. So if they sell they are better placed to pay off their mortgage and still have some of their savings.

But nationally prices have fallen 8 per cent from their peak, auction clearance rates and volumes have declined, and properties are taking longer to sell. In this environment, borrowers who fall into arrears find it harder to sell their property and repay their loan (Graph 4). Indeed, across the country, we see there is a strong relationship between recent housing price growth and the rate at which borrowers are leaving arrears. In those locations where housing price growth has been weaker, a smaller share of borrowers transition out of arrears.

The weaker housing market has also seen housing credit growth slow. Because loans tend to take some time to go into arrears, this has the effect of reducing the number of new loans that have repayments on schedule, and so increases the overall arrears rate. But our estimates suggest that slower credit growth accounts for less than one-tenth of the increase in the arrears rate since early 2016.

Another driver of arrears can be changes in interest rates. In the period before the GFC, arrears rates were rising despite strong economic conditions, in part because of large increases in mortgage interest rates. However, in recent years, interest rates on outstanding mortgages have been declining and so average mortgage interest rates have not contributed to the generalised increase in arrears.

Lending standards are also an important driver of arrears rates. Weaker lending standards mean that borrowers can get larger loans and more borrowers get loans with potentially riskier characteristics, such as interest only periods. For a borrower, the larger their required loan repayments relative to their available income, the slower they will be able to build up a buffer, and so the more likely they are to fall into arrears if their income falls or expenses rise. With weaker lending standards, more loans will be made to borrowers who are likely to experience difficulty repaying their loan, say because their income is less stable. For these reasons, weaker lending standards can lead to higher rates of arrears.

In Australia there has been a significant tightening of housing lending standards by the regulators of banks and other lenders, in earnest from around 2014. Regulators took these actions amid concerns that strong housing market conditions and strong competition by lenders had seen lending standards erode. The actions taken by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) included that banks apply more stringent interest rate buffers to maximum loan size calculations, increase their scrutiny of borrowers’ income and expenses, and reduce their share of lending with high loan-to-valuation ratios (LVRs). Complementing this, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) increased their focus on lenders’ compliance with responsible lending obligations, particularly in the area of interest-only lending.[4] These actions were designed to ensure that lenders only extend as much debt to borrowers as they will be able to repay, including a buffer.

Tighter lending standards should lead to lower arrears but this can take time to show up. Typically borrowers’ financial pressures build over time and so average arrears rates increase with time since loan origination, that is with ‘loan seasoning’.[5] For example, a three-year old loan is four times more likely to go into arrears than a one-year old loan. Another challenge of assessing the impact of lending standards on arrears is that different cohorts of loans experience common macroeconomic conditions at different times in their seasoning. If there is a sharp increase in unemployment in a given year, the cohort of loans originated one year earlier experience this with only 12 months of seasoning, while the cohort originated three years earlier experience it with 36 months of seasoning. This suggests that more recent loans would likely have a larger increase in arrears in response to rising unemployment.

Using the Reserve Bank’s Securitisation Dataset we find evidence consistent with more recent cohorts of loans having lower arrears rates than earlier cohorts. Specifically, those loans originated in the past few years have an arrears rate that is up to one-quarter of a percentage point lower than loans originated prior to 2014 (controlling for seasoning and common time effects such as the state of the economy) (Graph 5).[6] The lower arrears rates for more recent loans suggests these tighter lending standards have been effective.

However, in other ways, measures taken to improve lending standards may actually temporarily increase arrears rates. One measure addressed the large and increasing share of loans that were interest only, meaning the borrower was not required to make regular principal payments and so the loan size did not necessarily decline over time. In 2017, APRA imposed a 30 per cent benchmark for the maximum share of lenders’ new loans that could be interest only. That benchmark has since been removed. But, recognising the greater risk of interest-only lending, banks continue to charge higher interest rates for these loans and more carefully scrutinise their suitability for borrowers. As a result, some borrowers who may have anticipated being able to roll over an interest-only period are finding they cannot. Some are then facing temporary difficulty servicing the higher principal and interest (P&I) payments at the end of the interest-only period. However, most borrowers in this position get their repayments back on track within a year.

Tighter lending standards have made it more difficult for some borrowers to refinance their loan. In general, a borrower who, say, experienced a decline in their income may be able to reduce their repayments by refinancing with a loan that is at a lower interest rate or has a longer term and so lower repayments. But borrowers who are financially stretched are more likely to be constrained by tighter borrowing restrictions. If they can’t refinance and struggle to make their existing repayments, they are more likely to fall into arrears.

There have also been some reports that banks have been displaying greater forbearance, that is, allowing loans to stay in arrears for longer. Supposedly, this is in response to a recognition of, and attention on, some past poor lending decisions. However, it seems unlikely that this could explain a significant part of the increase in aggregate arrears. In an environment of falling housing prices, allowing a borrower to remain in arrears for longer would increase the loss that the borrower, and so the lender, is exposed to. This wouldn’t seem to be operating in the best interests of the borrower, or for that matter even the lender.

Summing up, housing arrears have risen but by no means to a level that poses a risk to financial stability. Several factors have been interacting to drive the rise in housing arrears. Economic conditions are undoubtedly part of the story. Weak income growth, housing price falls and rising unemployment in some areas have all contributed. But they have not acted alone, interacting with earlier weaker lending standards, and the more recent tightening in lending standards. To the extent that we can point to drivers of the rise in arrears, while the economic outlook remains reasonable and household income growth is expected to pick up, the influence of at least some other drivers may not reverse course sharply in the near future, and so the arrears rate could continue to edge higher for a bit longer. But with overall strong lending standards, so long as unemployment remains low, arrears rates should not rise to levels that pose a risk to the financial system or cause great harm to the household sector.

The founder and the executive team of online mortgage marketplace HashChing have all left the company, with a new interim CEO taking the helm, via The Adviser.

The founder and CEO of HashChing, Mandeep Sodhi, along with the key members of the executive team – including chief operating officer Siobhan Hayden and chief technology officer Vajira Amarasekera – all left the company at the end of May.

The fintech, which was officially launched by friends Atul Narang and Mandeep Sodhi in 2015 (before Mr Narang left the company in 2017), is an online platform that has pre-negotiated home loan deals that a consumer can access via a mortgage broker.

It had been increasingly looking at new ways to fund its growth and was recently looking to raise funds via a crowdfunding exercise, following its failure to raise $5 million last year via the same means.

In 2018, the mortgage marketplace also sought financial assistance from Jobs for NSW in the form of a $700,000 loan to create new jobs and allow the company to invest in the resources required to continue “expanding rapidly”.

While the company appeared to be operating as usual last month (when it announced it was introducing a deposit-free home loan product), HashChing has since seen a mass exodus of its entire leadership team.

None of the former members of the executive team were available to comment about the reasons for their departure – but out-of-office emails show that Mr Sodhi and Ms Hayden both ceased working at Hashching on 21 May 2019.

Future vision for the platform

A new interim CEO, Arun Maharaj, has now stepped in to head up HashChing and take it through a new “growth stage”.

HashChing will now focus on becoming a “one-stop digital platform” for all intermediated financial services, as part of a revamped strategy under the new executive leadership.

It is also now looking to a new product strategy to expand the platform’s business into brokering small-to-medium enterprise (SME) lending.

Sapien Ventures, together with the company’s second-largest institutional investor, Heworth Capital, will provide funding for the business at it expands to generate “convincing traction figures”, before going to the wider market for fresh growth capital later this year.

HashChing’s largest venture investor, Victor Jiang of Sapien Ventures, commented on the platform’s new strategy: “In the aftermath of the banking royal commission, the need to support the financing of SMEs through non-traditional channels has increased significantly. Coupled with the proliferation and increasing market adoption of fintech platform businesses, we believe that the time is now ripe for HashChing to enter into SME and commercial lending.”

“Through its online rating and ranking algorithms that help connect its customer with the most qualified financial service provider, HashChing has the potential to become the ultimate destination of choice for a range of intermediated financial services. In other words, the ‘Uberization’ of everything from personal mortgages, through to financial advice and SME lending,” he said.

Noting the departure of the original executive team, Mr Jiang commented: “As a board, we are very grateful for their tremendous contributions in getting the business to this point. Now with new capabilities, we look forward to seeing the business reach a new level of growth and expansion, as it is set to capitalise on a range of differentiated market opportunities.”

The new CEO, Mr Maharaj, added: “It’s time for a proven marketplace platform like HashChing to diversify its offerings and to think beyond the previous boundaries,” he said.

“This is an opportunity to evolve an emerging business like HashChing during its next phase of growth, to transition and position the platform into a global enterprise with multiple revenue streams.

“The scalability of such platforms are limitless, as has been demonstrated numerous times globally. I am thrilled to be taking on this challenge at this time and am excited to be part of this growth journey,” he said.

Mr Maharaj was formerly the CEO of stockbroker and wealth management firm BBY, before its collapse in May 2015 when 10 group companies were placed into external administration.

The number of mature age Australians carrying mortgage debt into retirement is soaring.

And on average each mature age Australian with a mortgage debt owes much more relative to their income than 25 years ago.

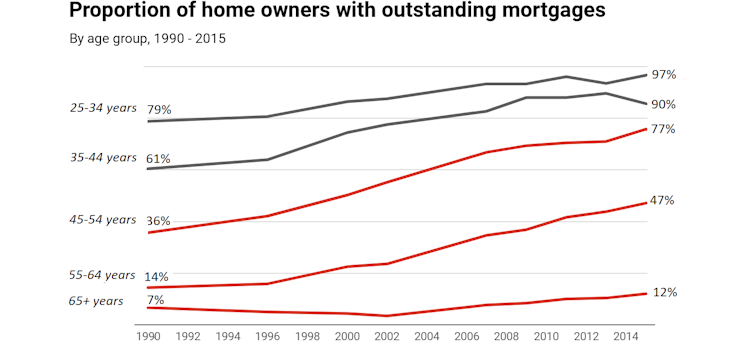

Microdata from the Bureau of Statistics survey of income and housing shows an increase in the proportion of homeowners owing money on mortgages across every home-owning age group between 1990 and 2015. The sharpest increase is among homeowners approaching retirement.

For home owners aged 55 to 64 years, the proportion owing money on mortgages has tripled from 14% to 47%.

Among home owners aged 45 to 54 years, it has doubled.

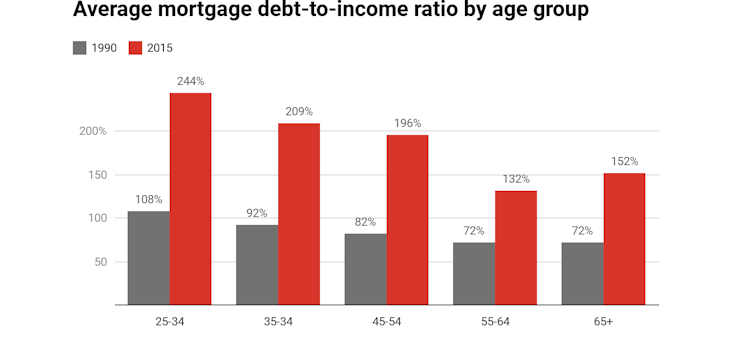

Meanwhile, the average mortgage debt-to-income ratio among those with mortgages has pretty much doubled across every home-owning age group.

In the 45-54 age group the mortgage debt-to-income ratio has blown out from 82% to 169%.

For those aged 55-64 it has blown out from 72% to 132%.

The soaring rates of mortgage indebtedness among older Australians have been driven by three distinct factors.

First, property prices have surged ahead of incomes.

Since 1970 the national dwelling price to income ratio has doubled.

Despite weaker property prices, the ratio remains historically high. This means households have to borrow more to buy a home. It also delays the transition into home ownership, potentially shortening the the remaining working life available to repay the loan.

Second, today’s home owners frequently use flexible mortgage products to draw down on their housing equity as needed for other purposes. During the first decade of this century, one in five home owners aged 45-64 years increased their mortgage debt even though they did not move house.

Third, older home owners appear to be taking on bigger mortgages or delaying paying them off in the knowledge that they can work longer than their parents did, or draw down their superannuation account balances.

For mortgage holders aged 55-64 years, there is evidence to suggest that larger debts prolong working lives.

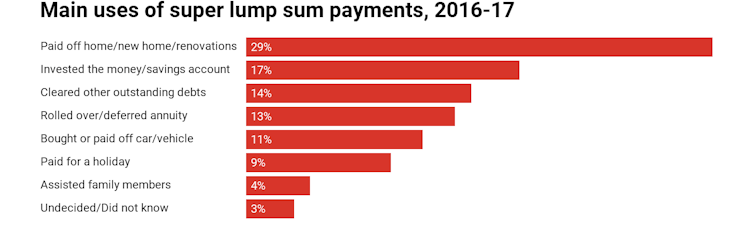

In 2017 around 29% of lump sum superannuation withdrawals were used to pay down mortgages or purchase new homes or pay for home improvements, up from 25% four years earlier.

In the Netherlands, where a mandatory occupational pension scheme along the lines of Australia’s super scheme has been in place for much longer, over one-half of home owners aged 65 and over are still paying off mortgages.

Internationally, studies have found that indebtedness adds to psychological distress. The impacts on wellbeing are more profound for older debtors, without the ability to recover from financial shocks.

Debt-free home ownership in old age used to be known as the fourth pillar of the retirement incomes system because of its role in reducing poverty in old age. It allowed the Australian government to set the age pension at relatively low levels.

Growing indebtedness will increase after-housing-cost poverty among older Australians and create pressure to boost the age pension.

Mortgage debt burdens late in working life will also expose home owners to unwelcome risks, as health or employment shocks can ruin plans to pay off their mortgages.

During the first decade of this century, around half a million Australians aged 50 years and over lost their homes.

Those losing home ownership are often forced to rely on rental housing assistance. Moreover, as older tenants they are unlikely to ever leave housing assistance. This will put pressure on the government to boost spending on housing assistance, which is likely to further boost demand for housing assistance.

Super and government housing assistance could become the safety nets that allow retirees to escape their mortgages.

It wasn’t the intended purpose of superannuation, and wasn’t the intended purpose of housing assistance. It is a development that ought to be front and centre of the inquiry into the retirement incomes system announced by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg.

It is a change we’ll have to come to grips with.

Authors: Rachel Ong ViforJ, Professor of Economics, School of Economics, Finance and Property, Curtin University; Gavin Wood, Emeritus Professor of Housing and Housing Studies, RMIT University

Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North discuss the latest trends in mortgage lending. Have the taps been loosened, and what are the implications?

The number of home loan applications received by the major bank in the week following the federal election hit a six-month high, according to CEO Matt Comyn, via The Adviser.

Following his address to the Trans-Tasman Business Circle, CEO of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) Matt Comyn revealed that the bank experienced a surge in home loan applications via both the proprietary and broker channel following the Coalition government’s election victory.

“I think, in particular at the moment, quite rightly, there is a strong interest in property,” Mr Comyn said.

“We did have the strongest week in applications that we have seen in more than six months. It did feel – certainly from a demand perspective – there is quite a shift in sentiment.”

The election outcome signalled the defeat of the Labor opposition’s proposed changes to negative gearing and the capital gains tax, which some observers feared would further dampen sentiment in the housing market.

Expectations of a rate cut from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) also heightened following the election, after governor Philip Lowe conceded that the central bank would “consider the case for a rate cut” in June.

Mr Comyn said the bank has revised its monetary policy forecast and now expects an imminent rate cut from the RBA; however, Mr Comyn downplayed its contribution to lifting market sentiment.

“It has an effect but there are other things that have a higher impact,” Mr Comyn added.

“Fiscal stimulus, cuts to taxes, and increases in sentiment tend to have a much bigger transmission effect to the broader economy.”

Further, commenting on the fall in home values, Mr Comyn said that the correction is an overall positive for the broader economy.

“It’s painful for anyone who owns a house and sees the value of their asset or any asset reduce, but I do think it’s a good thing,” he said.

“It’s in the interests of long-term financial stability.”

During his address, Mr Comyn unveiled a new “green mortgage” initiative, designed to reward “energy-efficient” mortgage holders.

Mr Comyn said CBA plans to pass on the benefits of continued demand for green bonds from investors, by offering $500 cashbacks to mortgage holders who have solar panels installed in their homes.

Commenting on the announcement, Daniel Huggins, CBA’s executive general manager, home buying, said: “We are always looking for innovative ways to support our customers, which is why we are launching this new initiative.”

He added: “We understand many of our home loan customers could reduce their energy volume and usage and pay less or become net positive for energy by investing in energy efficient devices.”

Mr Huggins said the bank is in the process of introducing other initiatives to encourage home owners to make “greener choices”.

“We want to support more of our customers who wish to install small scale renewables by reducing their installation costs and payback periods,” Mr Huggins added.

CBA stated that the green mortgage initiative will be formally launched in the coming weeks.