More than two in five prospective home buyers have admitted to not understanding Lenders Mortgage Insurance (LMI), according to new data.

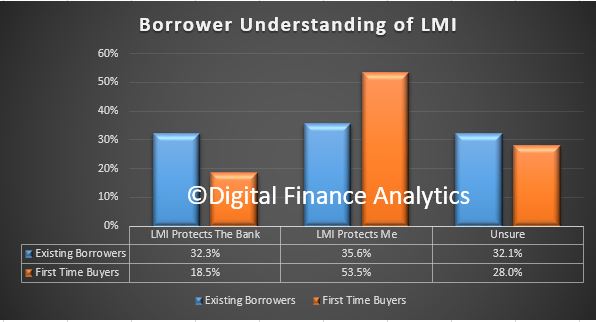

This chimes with our research on the topic of LMI from our own surveys. In fact the confusion varies by type of buyer, and who is protected. First Time Buyers are a particular concern. See our previous post “Is Lenders Mortgage Insurance a Good Thing“.

Mortgage Choice and CoreData’s new Evolving Great Australian Dream 2018 whitepaper found 42.1% of respondents said they were not sure what LMI was, yet a third (32%) said they would need to pay it in order to get into the property market.

“Our data found that a majority of home buyers are in the dark when it comes to Lenders Mortgage Insurance and what it entails,” Mortgage Choice Chief Executive Officer Susan Mitchell said.

“According to our survey, only 32.1% of prospective buyers accurately stated that LMI is designed to protect the lender if a borrower can’t repay their mortgage.

“Another 8.2% of respondents thought LMI protected the borrower, while 17.6% believed it protected both the borrower and the lender,” said Ms Mitchell.

The research found that 44.8% of women did not to understand what LMI was, compared to 37.35% of men.

Buyers aged 29 and under (47.3%) were the most likely not to know what LMI was, while the 50 to 59 age group (40.75) had the highest proportion of buyers who knew what LMI was.

On a state by state comparison, Victoria (46%) had the highest proportion of buyers who did not know what LMI was, followed by Queensland (40%) and Western Australia (39.6%). NSW buyers topped the states when it came to correctly defining LMI at 34.6%.

Ms Mitchell said it was concerning that such a large proportion of Australians had either a limited or no understanding of LMI and that mortgage brokers can play an educational role for borrowers.

“For many first home buyers, LMI is likely to be a cost they have to pay to get into the property market, particularly if they do not have a deposit that is at least 20% of the purchase price,” she said.

“The reality is that saving for a home deposit is a major challenge for first home buyers and this has been the result of strong price growth over the last few years.

“According to CoreLogic, the median dwelling value in Australia is $554,605, and for a first home buyer to avoid LMI, they would need to save $110,921 for a 20% deposit and they would still need to have additional funds to cover costs such as legal fees and stamp duty.

“That is quite large sum to save and it only increases if a buyer is looking in cities such as Sydney and Melbourne.

“While LMI on the surface seems like a fee to be avoided, it does have the benefit of helping a buyer purchase a home with a smaller deposit, thereby allowing them to get onto the property ladder sooner rather than later.

“A buyer can choose to delay their property purchase to save a sufficient deposit, but the reality is property prices have risen consistently and the longer they delay, the more likely they are to miss an opportunity.

“Ultimately, in the long run, LMI is a fairly small expense in the overall cost of purchasing a home.”

Ms Mitchell said first home buyers could avoid LMI altogether if they were able to receive some sort of financial boost or a have a guarantor on their loan.

“First home buyers can avoid LMI by having a parent or family member go guarantor on their home loan, which then allows them to purchase without a 20% deposit” she said.

“In the case of the latter, it is important to note that lenders may require that any monetary gift must be held in an account for at least three months before home loan approval. Also, a lender may still require a borrower to demonstrate that they have 5% genuine savings.”

Ms Mitchell said it was important for first home buyers to have a good understanding of the purchase process.

“If you’re a first home buyer, you should speak to a mortgage broker who can guide you through the process of purchasing a property, from getting the best rate as part of the home loan application, through to settlement.

“They can explain the various options and costs involved, including LMI, thereby ensuring that you can confidently achieve your goal of home ownership,” concluded Ms Mitchell.

“As property prices continue to relax there has never been a better time for first home buyers to purchase. Therefore, it’s essential they have a clear understanding of LMI so that they know how it affects their ability to get into the market.”