As a young bank analyst learning the trade in the early 1990’s, understanding credit and capital was the primary focus. Discussions with seasoned bank credit officers provided much insight and learnings.

In credit, I learnt that security/collateral is ‘makeweight’ and one should only lend on ability to service and repay from cash flow. Hence the old mortgage lending rule of thumb; lend no more than 3x gross income unless it’s a doctor, then maybe stretch it to 4x. On this basis, a loan is generally repaid within 10 years, ceteris paribus – a suitable outcome for both lender and borrower.

In the UK, this is embedded in regulation. The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) ensure that mortgage lenders do not extend more than 15% of their total number of new residential mortgages at loan to income (LTI) ratios at to or greater than 4.5x.

Understanding the borrower’s capacity to service as time moves on is paramount. Many bank bad debts are caused by future changes in borrower circumstances. Accordingly, a bank’s corporate loan book is generally reviewed annually.

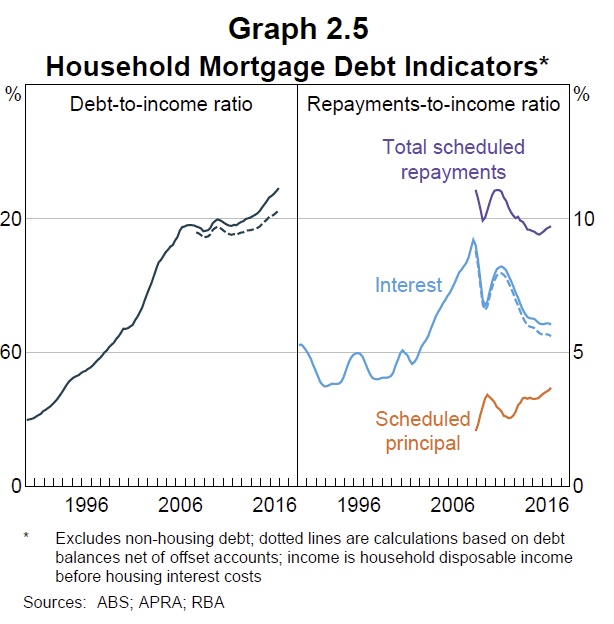

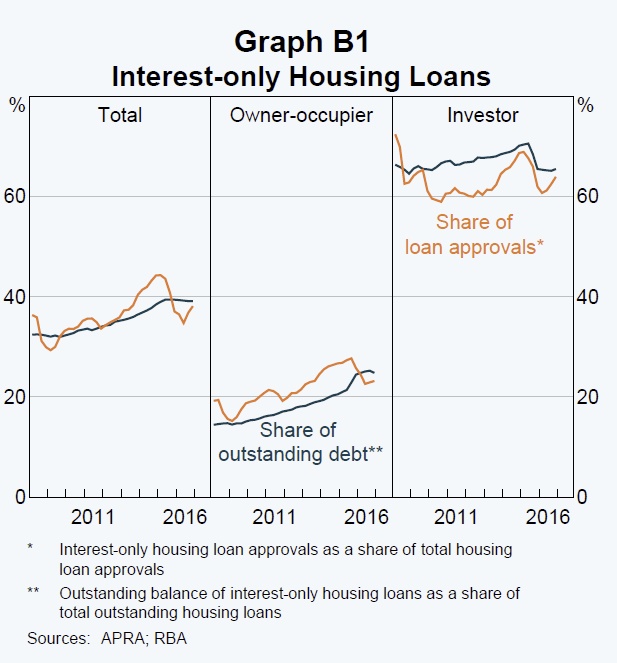

However, mortgages don’t have the same level of scrutiny, yet the amount borrowed could be higher and the lender more exposed. Take the eventual transition from “interest only” to “principal & interest”; where does the borrower find the additional 40% repayment obligation?

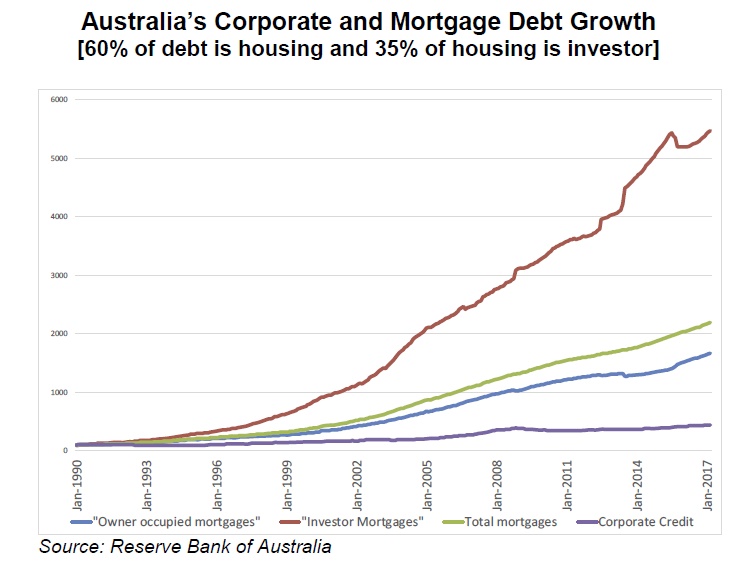

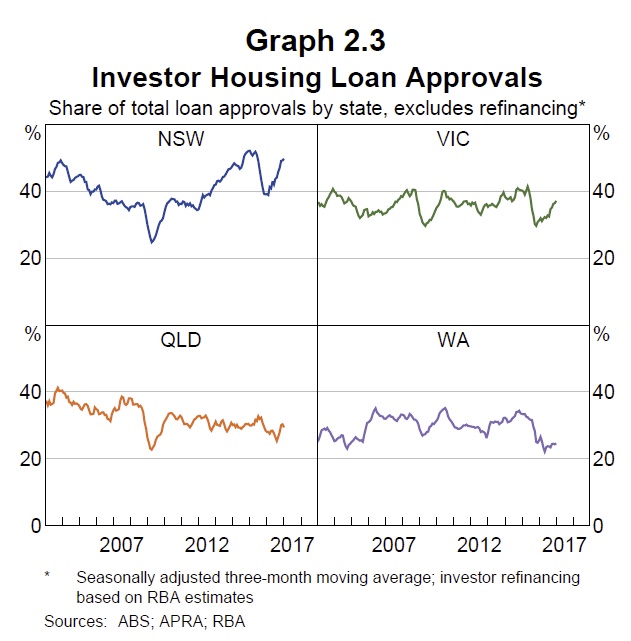

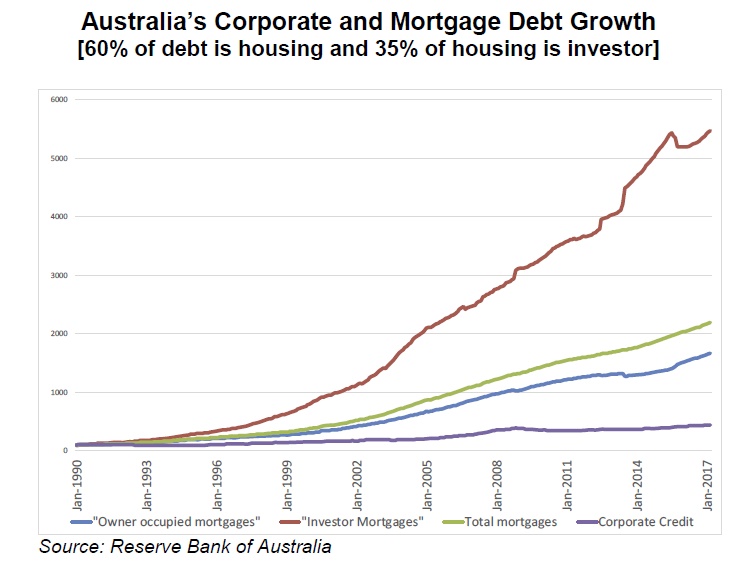

The Australian credit system now looks over exposed to one asset class – the residential home. A function of both very low mortgage credit risk weights and the disintermediation of corporate debt.

Given the dynamics of the Australian housing market over the last three to five years; low interest rates, proliferation of interest only products coupled with low income and employment growth, the embedded risks in the mortgage system have increased materially.

Given the dynamics of the Australian housing market over the last three to five years; low interest rates, proliferation of interest only products coupled with low income and employment growth, the embedded risks in the mortgage system have increased materially.

When one scrutinises the typical bank earnings release (some 250 pages of information), the loan to income ratio is not mentioned or disclosed, yet it is one of the most important credit metrics for an analyst/investor to

understand.

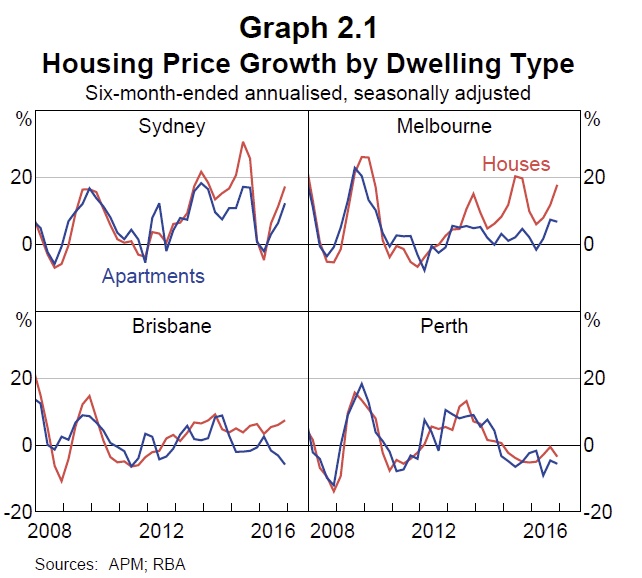

We suspect the old 3x gross income rule has been fundamentally breached. Data from the RBA, HILDA, APRA and the major banks, plus our own proprietary sources confirm this. Indeed, we believe gross incomes could have been capitalised to well over 6x, which would partly explain the rapid increase in Melbourne and Sydney house prices.

What is the difference between 3x and 6x? At least 15 years in repayment terms, assuming no material change in income and the level of interest rates. However, the Australian cash rate has never been lower than its current 1.50%, and the rest of the developed world is beginning to move rates up.

A recent conversation with a high-end Sydney mortgage broker was a revealing insight to practices “if we included private school fees and child care costs, there would be no borrow”. Expenses are quite simply fudged. Gone is, the historical rational reliance on gross income and 3x that as the maximum mortgage lend. The banks appear to have weakened underwriting standards to pursue the asset backed lend – sustaining credit fuelled house prices.

Then consider the mortgage broker revenue model. An upfront payment of ~65bps and a trail of ~16bps – this makes large interest only mortgages very lucrative.

As exuberance towards the Australian home grew to now irrational levels, the old credit rules of thumb appears to have been left by the wayside. Banks talk about mortgage account numbers, but not values. Banks talk about LVRs, but not LTIs. Banks talk about averages, but not distributions. And Banks talk about loss rates of a mere 2bps, but fail to capture a full credit cycle.

We draw from the paper “Stabilising and Healing the Irish Banking System: Policy Lessons” Dirk Schoenmaker, Duisenberg School of Finance 12 January 2015. The Minsky ‘financial instability’ hypothesis captures the typical credit cycle quite well; five stages from the emerging boom to the eventual bust … human behaviour the primary driver:

1. Credit expansion: characterised by rising asset prices;

2. Euphoria: characterised by overtrading;

3. Distress: characterised by unexpected failures;

4. Discredit: characterised by liquidation; and

5. Panic: characterised by the desire for cash

Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis highlights the procyclicality of the financial system; risk is under-estimated in good times, and overestimated in bad times. Moreover, the more debt is built up in the upswing, the more severe is the deleveraging in the downswing. Thus, the importance of equity capital for banks. Financial fragility builds over time as information about counterparties decays; the loan to income ratio underwriting discipline is lost. A crisis may arise when a (possibly immaterial) shock causes lenders to suddenly have incentives to produce information, what is the loan to income ratio?

Could the current action in the Federal Court of Australia, Australian Securities and Investment Commission vs. Westpac Banking Corporation, be that seemingly small shock that causes lenders and investors to request more information and adjust future mortgage sizes? The marginal buyer is then less financially equipped to pay more. ASIC simply has to establish that Westpac breached provisions of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 that require a lender to assess whether a loan would be ‘unsuitable’ for the consumer (sections 128, 131 and 133). While the Act does not define, what constitutes an ‘unsuitable’ loan, section 131(2) expressly provides that a loan must be assessed as ‘unsuitable’ if the consumer will be, or is likely to be unable to meet their payment obligations either at all, or only with substantial hardship (section 131(2)(a)).

Or, could it be the Regulators and Central Bankers eventual understanding of the embedded risk in the Australian mortgage system that will cause them to respond with further control and restriction? Credit fuels a bubble, and its ultimate rationing and eventual withdrawal deflates it. In Ireland, it is postulated by Schoenmaker that “‘Groupthink’ among bankers, supervisors and central bankers may explain that the dangers of the strong build-up of house prices were not appreciated” – The euphoria stage, where capital misallocation exacerbates the fervour.

This is where we are today

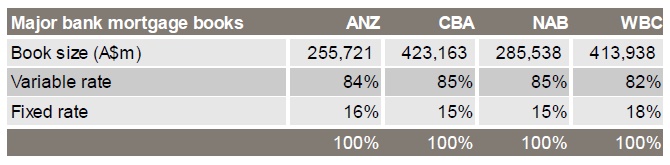

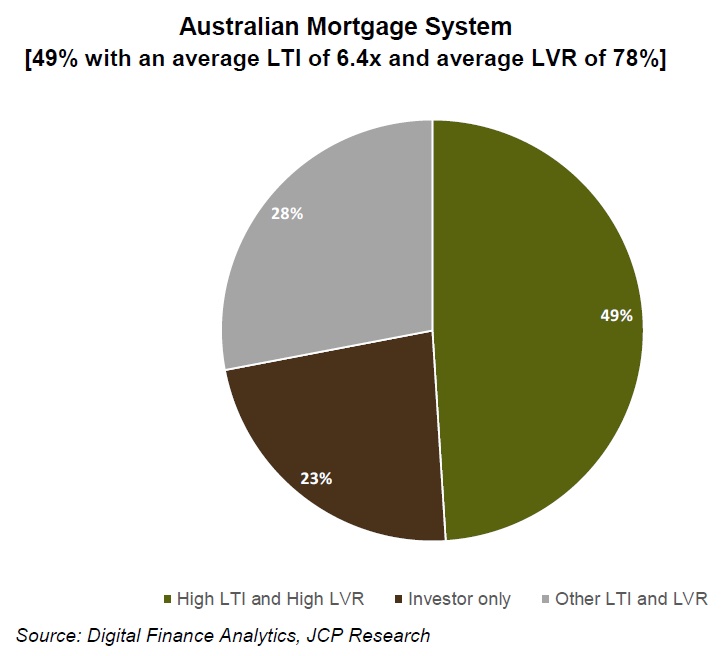

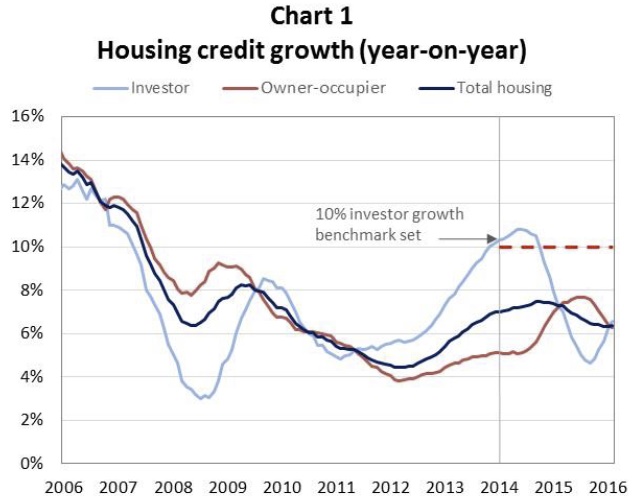

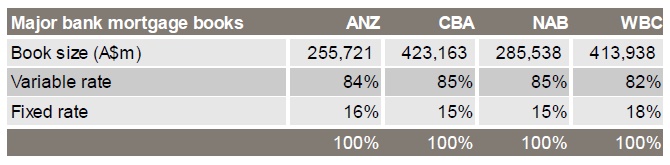

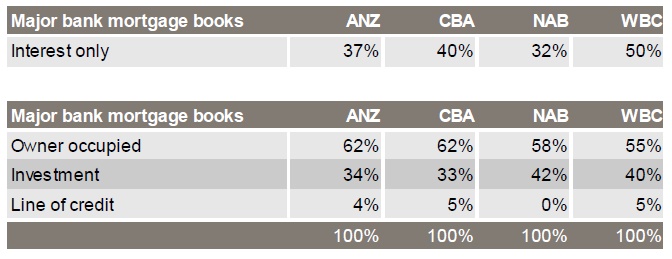

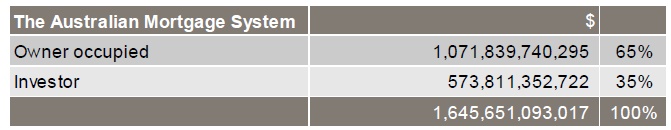

Post the global financial crisis of 2007/08, most economies de-levered. However, in Australia we kept on going on, 6% cagr owner occupied mortgage growth and 8% cagr investor mortgage growth. Interest only loans were ~30% of mortgage credit in 2012, today they’re ~42% and well above investor credit: Westpac is especially concerning at 50%.

Proprietary data

Proprietary data

Collecting quality information is central to our research process. We have assembled a range of data from APRA, the RBA, the ABS, HILDA, the major banks and Digital Finance Analytics.

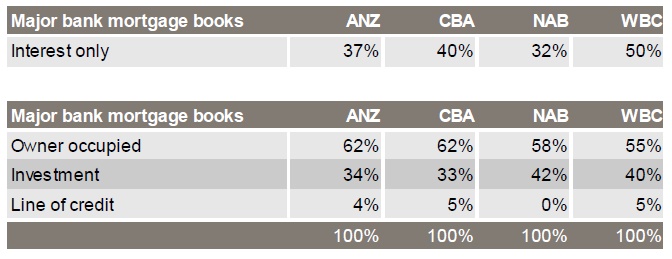

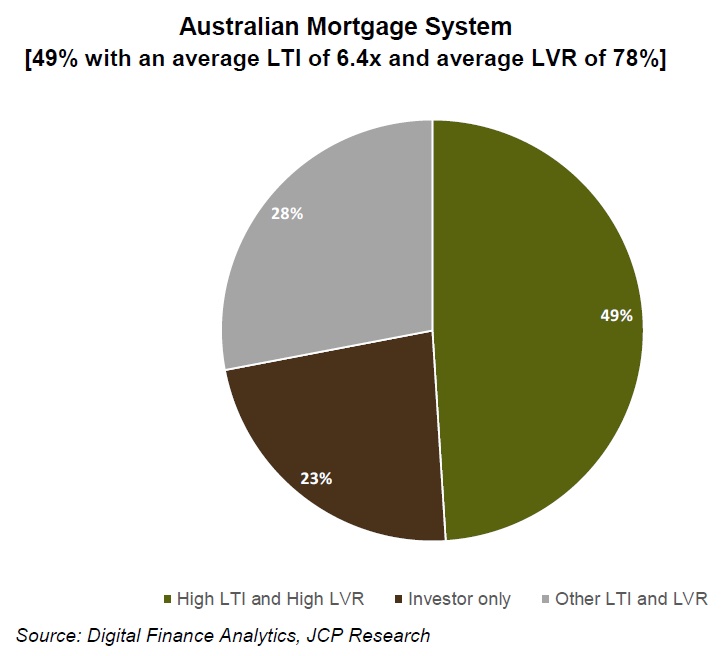

We then ran a query which broke down the mortgage system, by value, on two metrics – Loan to Income (“LTI”) and Loan to Value (“LVR”). Both metrics are dynamic, in that they pick up current income and current collateral values. By value is an important distinction as most of the Banks’ publish data averages, and distributions by number.

There are enough very low mortgage accounts which distort the averages. It is not uncommon for a borrower to essentially fully pay the mortgage but keep the account open with a nominal outstanding amount as a “rainy day” facility.

The findings

- 49% of credit outstanding is held by households

with: Current LTI ratio > 4.0x; the average LTI is 6.4x

- Current LVR > 50%; the average LVR is 78%

- These households represent 70% of owner occupied credit.

At first glance this was somewhat of a surprising outcome. But when put into the context of very low interest rates, the proliferation of interest only mortgages and the rapid appreciation of house prices in Sydney and Melbourne, it makes more sense.

At first glance this was somewhat of a surprising outcome. But when put into the context of very low interest rates, the proliferation of interest only mortgages and the rapid appreciation of house prices in Sydney and Melbourne, it makes more sense.

Older loans (7+ years) started much smaller, are more likely paired with houses that have risen substantially, and more likely to be amortising (not interest only).

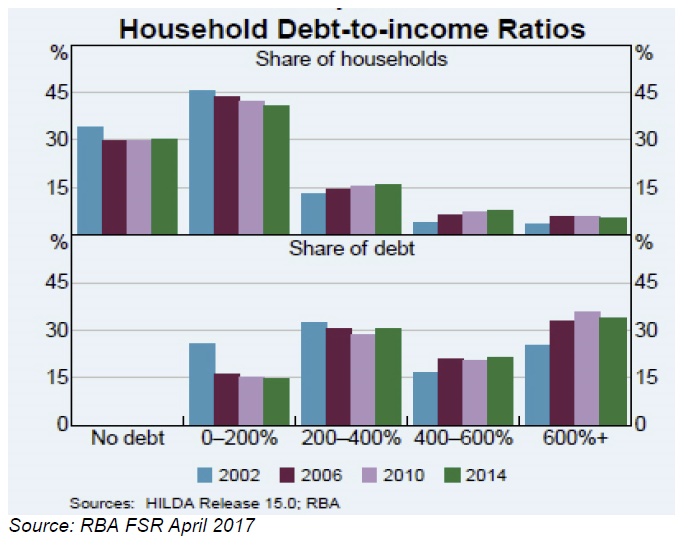

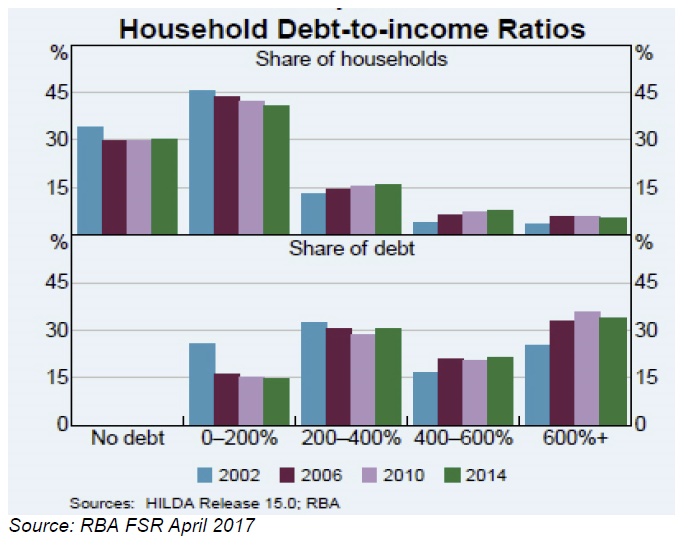

These results are corroborated with the RBA’s recent Financial Stability Review analysis of the 2014 HILDA data (shown below). More than 50% of debt was held by household, with a 4.0x or larger LTI, regardless of LVR. Our analysis suggests the level has increased a further 5-10% since 2014.

We identified three specific cohorts that appear to pose the most risk:

We identified three specific cohorts that appear to pose the most risk:

- Professional Households

- Young Pretenders with stretched budgets

- Young Families

Almost one third of the High LTI / High LVR exposure is held by high income households with an average of $250k in gross income. Despite being less than 2% of all households they represent 17% of the mortgage book, with an average mortgage outstanding of $1.6m. In addition, almost half have an investment property loan also.

Younger households last into the property market always suffer; amongst these we identify two groups with high LTI’s and high LVR’s; the “Young Pretenders” and “Young Families”. Bank lending behaviour has put these groups at risk also.

The “Young Pretenders” with an average income of $110k and a mortgage outstanding of $810k are burdened with an eye-watering average LTI of 7.4x. Despite being less than 0.5% of households, they represent 2.5% of the mortgage book.

The “Young Families” with high LTI and high LVR appear slightly better placed, with $80k in gross income vs. $420k mortgage outstanding. Clearly less leverage, and only 4.1% of the book, but with question marks surrounding treatment of expenses in home loan applications, and generally high costs of living faced by this cohort, actual stress may be very high.

Interest only could be Australia’s sub-prime. Interest only loans proliferate throughout the mortgage book, across cohorts and circumstances. Only one trend emerges; interest only households tend to have lower incomes and higher amounts of credit outstanding and tend to use interest only to borrow more. With caps on interest only loans, only time will tell if such households can afford the mortgages they have.

Buffers are sometimes touted as the offset to systematic stress in the mortgage book. However, our analysis shows the buffers primarily reside with the low risk cohort. That is 60% of the buffers (five months) are with the low risk households with low LTI’s and/or low LVR’s, this cohort represent only 30% of the debt. The borrowers who need the buffers don’t have them.

Needless to say, the system looks vulnerable. The old LTI ratio has left the banking lexicon, exposing a risk that we may have over capitalised incomes and hence over extended credit into certain cohorts.

The long virtuous housing wealth cycle could easily transition to a vicious cycle. Smaller mortgages to deleveraging, flat to decreasing house prices and exuberant to melancholic animal spirits will likely expose much bad lending behaviour.

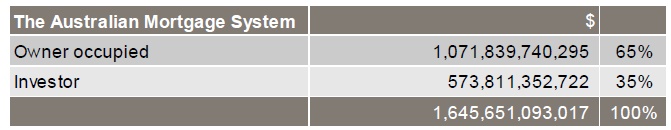

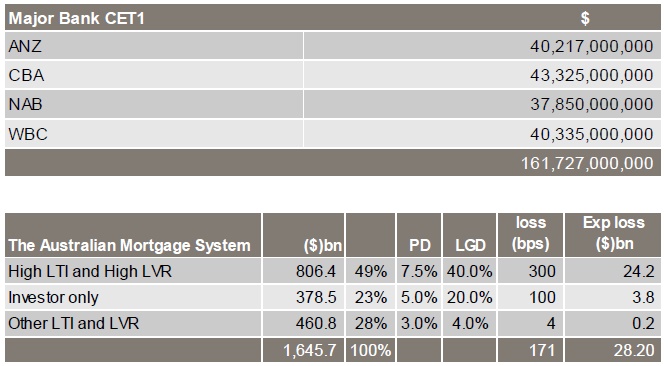

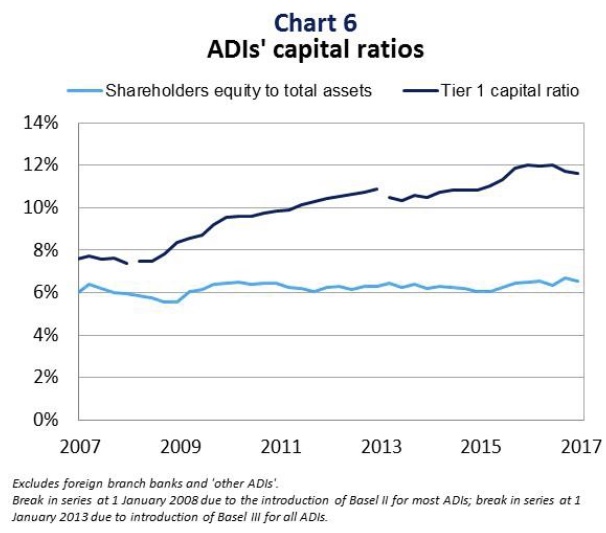

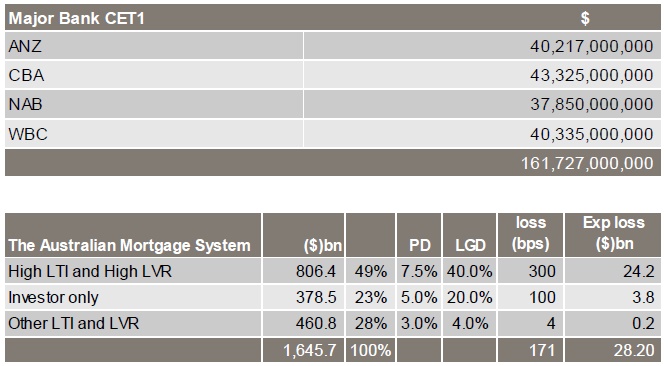

If we breakdown the system by our cohorts and apply a sensible Probability of Default (PD) and Loss Given Default (LGD) to each, 20% of bank equity capital is at risk (refer tables below). If we apply the Irish scenario to the high-risk cohort; 20% impairment rate with 50% provision cover, then 50% of bank equity capital is destroyed.

Ten years on, the Irish mortgage system remains weighed down with 25% non-performing loan ratios, as banks balance antiquated personal insolvency laws, politics and hope for economic recovery and write backs. Caught in the middle of the Anglo-Saxon system of easy credit provision and the Roman system of strong creditor’s rights.

Probability of default (PD) – the likelihood of a default over a time horizon. It provides an estimate of the likelihood their a borrower will be unable to meet its debt obligations.

Loss given default (LGD) – is the share of an asset that is lost if a borrower defaults.

20% of Equity Capital at Risk

The Australian mortgage system, February 2017.

Latest reported major bank core equity positions and forecast losses given likely PDs and LGDs.

Latest reported major bank core equity positions and forecast losses given likely PDs and LGDs.

PDs and LGDs formulated based on APRA tables and JCP judgement.

In summary, we see significant risk in Australian commercial bank lending books. The risk in a banks book is a function of recent lending behaviour, especially in a market with low rates, high interest-only shares, and quickly growing prices.

In summary, we see significant risk in Australian commercial bank lending books. The risk in a banks book is a function of recent lending behaviour, especially in a market with low rates, high interest-only shares, and quickly growing prices.

Reproduced with permission.