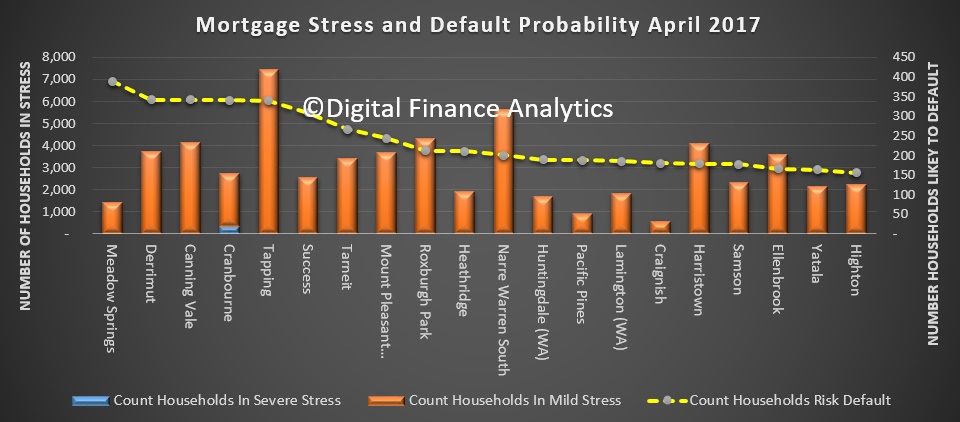

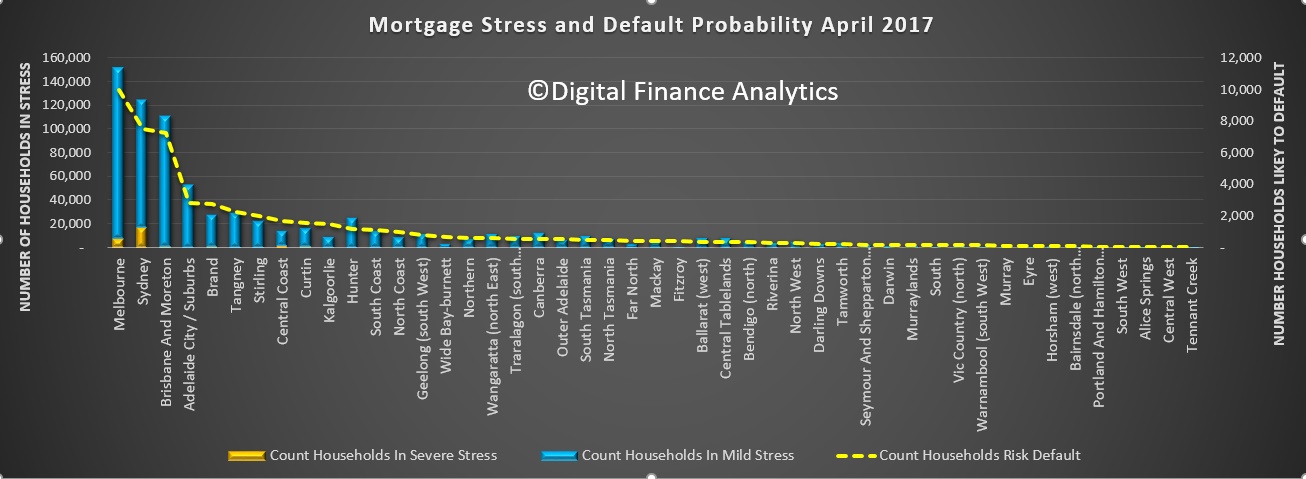

Today using our latest mortgage stress and probability of default data, we explore the top ten highest risk post codes across the country. Specifically, we look at where we expect the largest number of mortgage defaults to occur over the next few months.

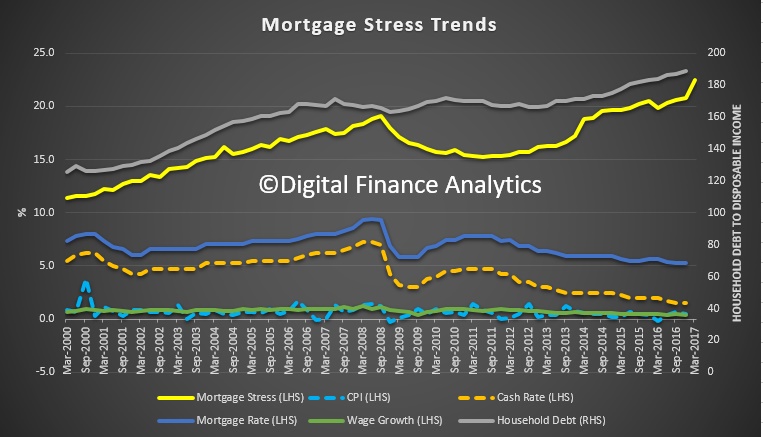

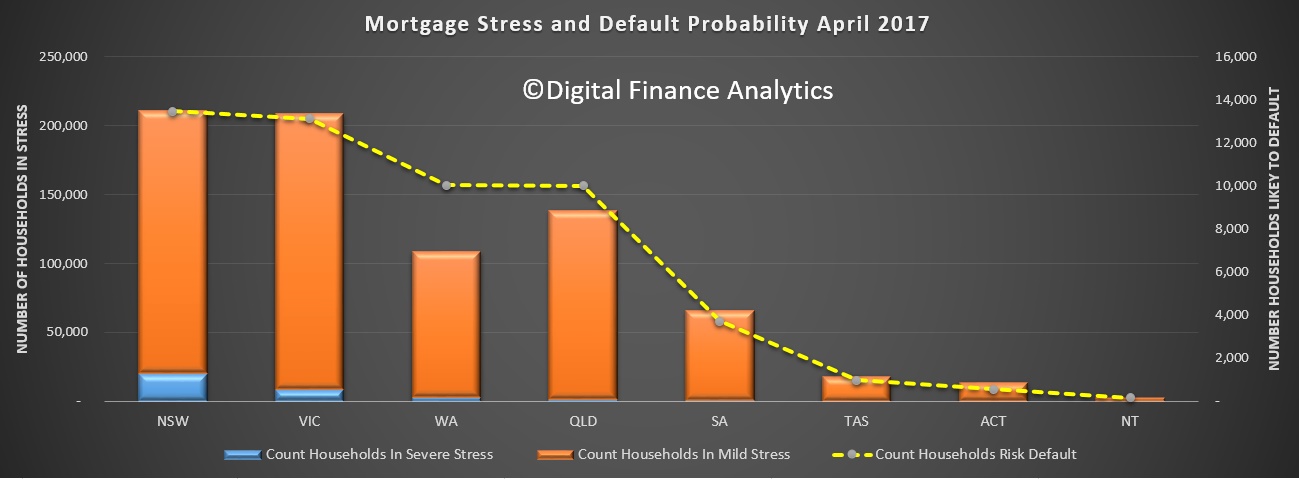

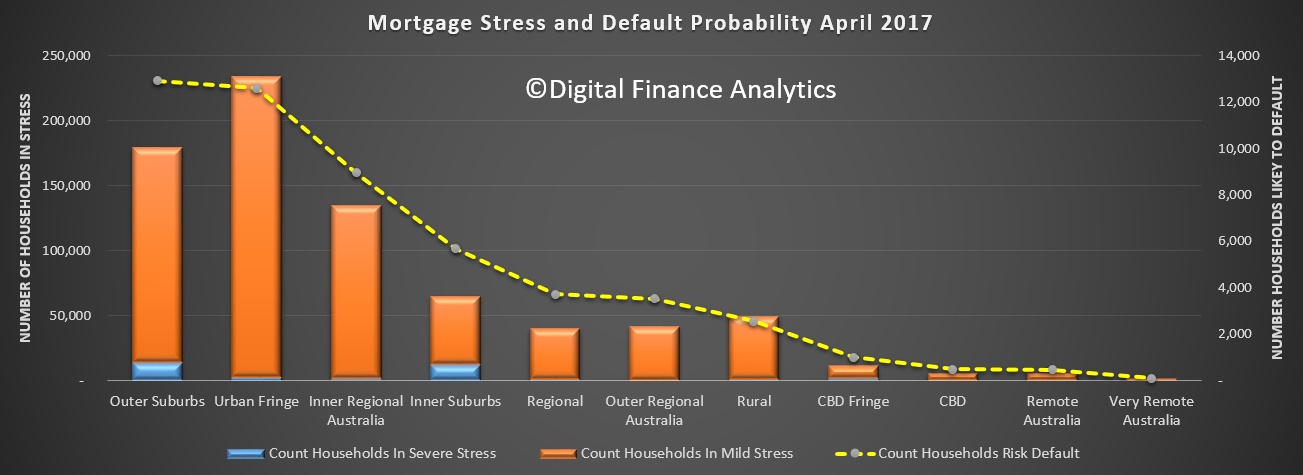

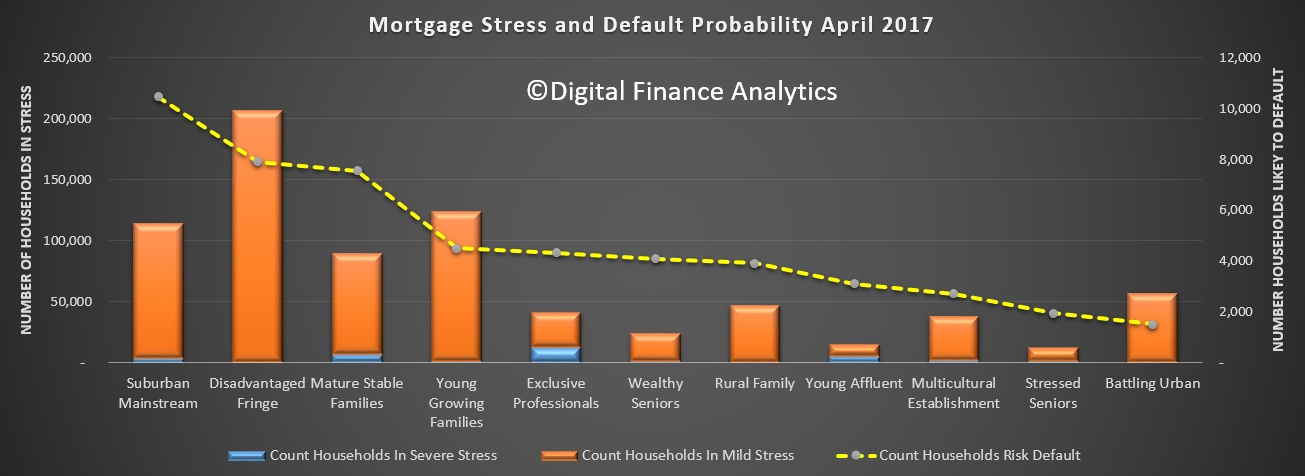

We explore the latest mortgage stress and default modelling, using data to the end of April 2017. We have already highlighted that overall mortgage stress is rising, with more than 767,000 households in stress compared with last month’s 669,000. This equates to 23.4% of households, up from 21.8% last month. 32,000 of these are in severe stress. We also estimate that nearly 52,000 households risk default in the next 12 months.

But now we look at individual post codes, and explore the top ten based on the number of households we expect to default. This is calculated using our 52,000 household sample with economic overlays for employment, inflation, interest rates and costs of living.

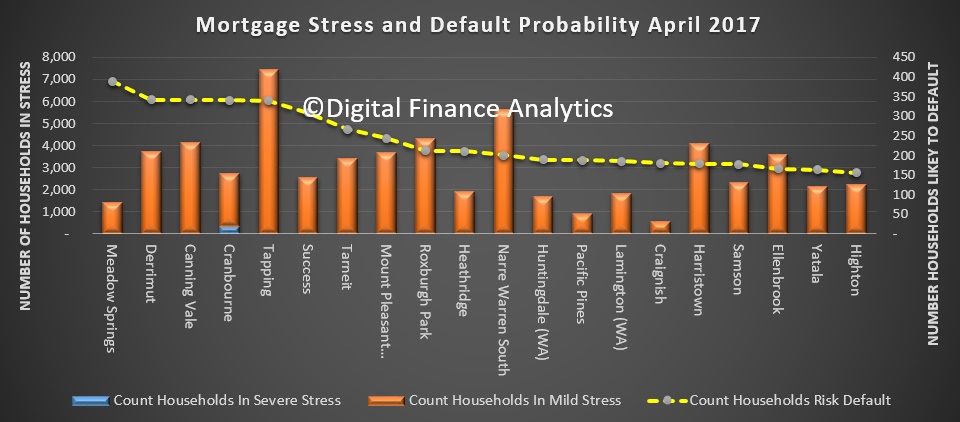

Note the labels in the chart above are only examples of locations within the postcodes.

Note the labels in the chart above are only examples of locations within the postcodes.

As a general observation, many of the worst hit post codes are areas containing large numbers of newer property in the outer urban ring. Households here have large mortgages and limited income growth relative to house prices. But there are some important differences in terms of recent house price movements across the post codes.

We will count down the top 10, from 10th down to the highest risk postcode. So stay with us to the end!

The tenth highest risk post code in Australia is 6027 in Western Australia. This is the city of Joondalup and includes places like Ocean Reef and Edgewater. It is about 25 kilometres north of Perth. It’s a fast growing area with lots of young families, lots of new homes and large mortgages relative to income. The average house price is $510,000, down from $570,000 in 2014. We estimate there are more than 1,900 households in mortgage stress in the area, and 211 are likely to default in the next few months.

In ninth spot is Victorian post code 3064. This includes Craigieburn, Mickleham and Roxburgh Park. This area is about 25 kilometres north from Melbourne. The average house price is $438,000, up from $330,000 in 2014. Again it is a fast growing area, with more than 60% of households holding a mortgage. The average age here is 30 years. We estimate there are 4,320 households in mortgage stress, and 212 are likely to default in the next few months.

Next at number eight is 4740 in Queensland. This includes Mackay and the surround areas, including Alexandra, Beaconsfield, Richmond and Slade Point. This area is more than 800 kilometres north of Brisbane, and is the gateway to the Bowen Basin coal mining reserves of Central Queensland. The average house price is $240,000 compared with $400,000 in 2014. We estimate there are more than 3,600 households in mortgage stress in the region, and 244 are likely to default in the next few months.

We go back to Victoria for the seventh placed postcode which is 3029, Hoppers Crossing. This is a suburb of Melbourne about 23 kilometres’ south-west of the CBD and has grown to become a substantial residential area, with about half of properties there mortgaged. The average age is around 35. The average house price is $440,000 compared with $340,000 in 2014. We estimate there to be more than 3,400 households in mortgage stress, and we expect 266 households to default in the next few months.

In sixth place in Western Australia, is 6164, the city of Cockburn. It is about 8 kilometres south of Fremantle and about 24 kilometres south of Perth’s central business district. It includes areas like Jandakot, South Lake and Success. Around 40% of homes in the region are mortgaged and the average age is 31 years. Average house prices are around $730,000 about the same as in 2014. More than 2,530 households are in mortgage stress here, and the estimated number of defaults in the next few months is 308.

Next, counting down to number five, is another WA location, 6065, the city of Wanneroo which is around 25 kilometres north of Perth on the rail corridor. Again a fast growing suburb, the city has had the largest population expansion out of any other local government area in greater Perth. The average house price is $425,000 compared with $480,000 in 2014. Nearly half of households here have a mortgage, and more than 7,400 are in mortgage stress. We estimate that 339 households are likely to default in the next few months.

In fourth spot is Cranborne in Victoria, 3977. It is a suburb in the outer south east of Melbourne, 43 kilometres from the central business district. Its local government area is the City of Casey which is one of Victoria’s most populous regions, with a population of well over a quarter of a million. The average house price is $425,000 compared with $330,000 in 2014. In 3977, close to half of all homes are mortgaged, and we estimate 2,750 households are in mortgage stress, including 344 in severe stress. We estimate around 340 households will default in the next few months.

So down to the top three. The third most risky postcode according to our analysis is Victorian post code 3030 which is the region around Derrimut and Werribee. Werribee is a suburb of Geelong and is about 29 kilometres south west of Melbourne. The median house price is $405,000, well above its 2014 level of $310,000. Here 3,730 households are in mortgage stress, and 342 are likely to default in the next few months.

In second place is another Western Australian post code, 6155, Canning Vale and Willetton. It’s a large southern suburb of Perth, 20 kilometres from the CBD. The population has been growing quickly with significant new builds, and 60% of households have a mortgage. The average house price is around $560,000, down from $610,000 in 2014. The average age is 32 years. We estimate there are 4,150 households in mortgage stress and 342 households risk default in the next few months.

So finally, in top spot, at number one, is another Western Australian postcode 6210, Mandurah. This also includes suburbs such as Meadow Springs and Dudley Park. Mandurah is a southwest coast suburb, 65 kilometres from Perth. The average home price is around $300,000 and has fallen from $340,000 since 2014. Here there are 1,430 households in mortgage stress but we estimate 388 are at risk of default in the next few months.

As a final aside, in twenty second place, is the highest risk postcode in New South Wales, 2155, Kellyville, which is 36 kilometres north-west of the Sydney central business district in The Hills Shire. The average house price here is $1.1 million, compared with $860,000 in 2014. We estimate there are 1,240 households in mild stress and we estimate 151 households risk default in the next few months.

So that completes our analysis of the current most risky postcodes. We will update our modelling next month, so check back to see how the trends develop. But in summary households in Western Australia are most exposed in the current environment, especially with house prices there falling.