An appallingly perfect storm is brewing for the federal budget:

- a government with much more income than expected

- a federal election due within months

- a government well behind in the polls

With the election all but announced for May, next Monday’s Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) will be the effective start of the campaign.

The latest figures put the government’s budget position about A$10 billion better than was expected when it was delivered last May.

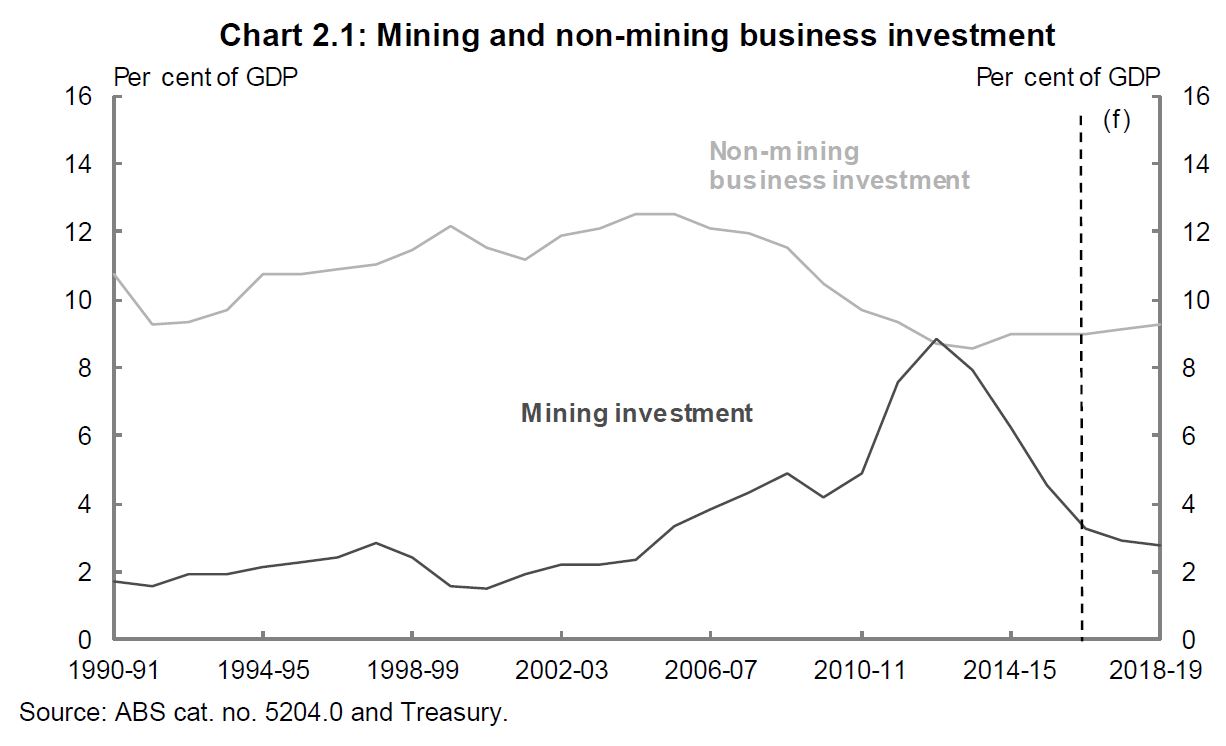

The budget has been gifted much higher revenues from corporate income taxes, almost entirely driven by mining companies selling more than they expected (at higher prices than they expected) to China.

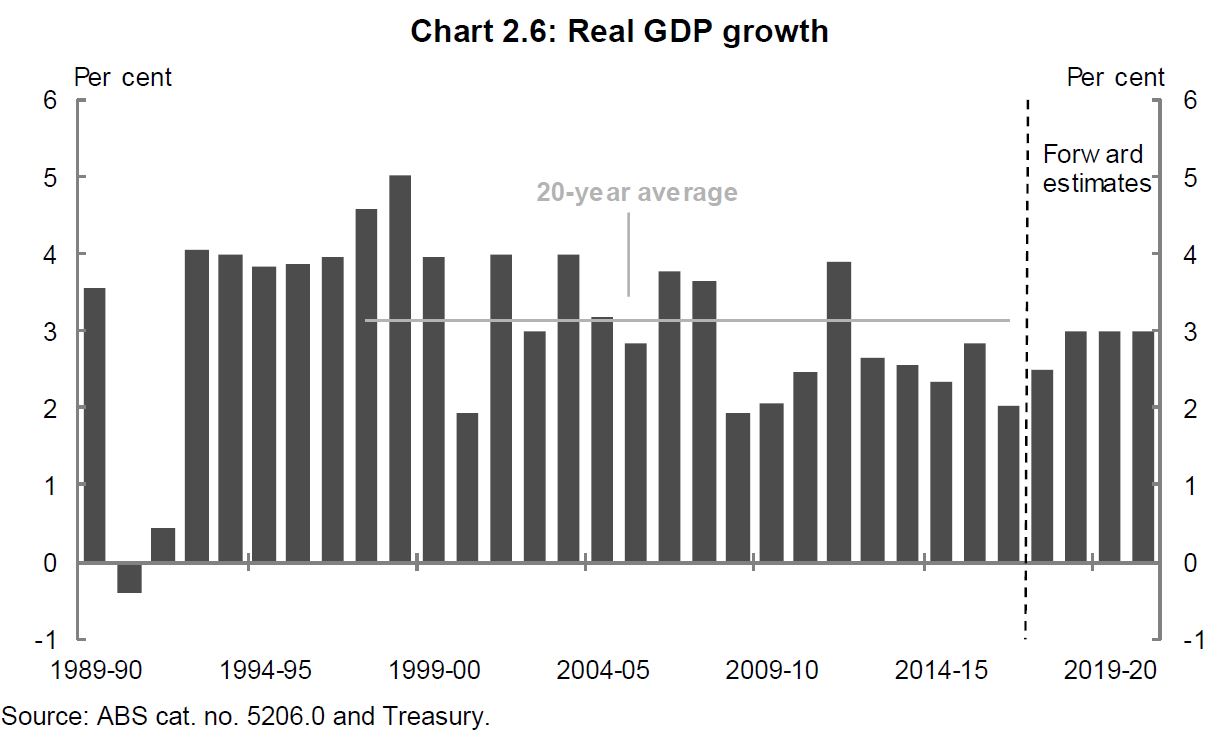

A stronger than expected domestic economy has also helped, producing small upside surprises in various other taxes and cutting the need for government spending.

In the past six months the stars have aligned to hand the government a virtual war chest with which to fight the election.

A full MYEFO, then an election budget

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has laid out the timetable.

MYEFO is due on Monday December 17 and an early Budget will be handed down on Tuesday April 2, days before the government is expected to call the May election.

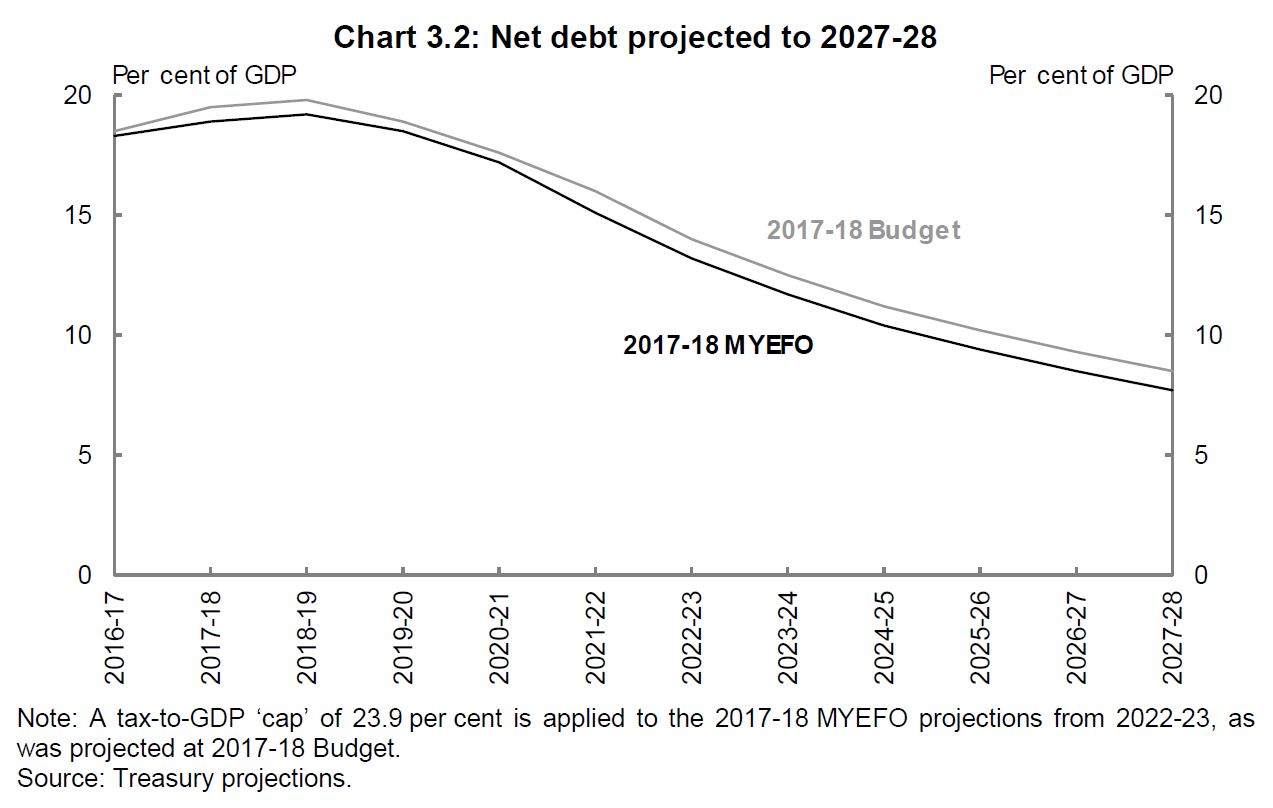

In announcing it, he promised to deliver a budget surplus in 2019/20.

This tells us two things, firstly, that he has zero interest in bringing that surplus forecast forward to the current financial year, 2018-19; and second, that that surplus is unlikely to be materially different from what Morrison previously forecast (as treasurer) in May.

That will give him room to make some very expensive announcements.

With as much as (or more than) an extra A$10 billion per year to play with, Morrison’s ministers will be rubbing their hands together working out how to get the most electoral bang for the bucks.

Endangering the budget long term

This does not bode well for government finances beyond the next few years.

Highly targeted spending measures aimed at improving election prospects are rarely the best use of public funds.

New spending commitments in the just past few months are set to cost the budget just under A$500 million this year, rising to almost A$1.5 billion next year.

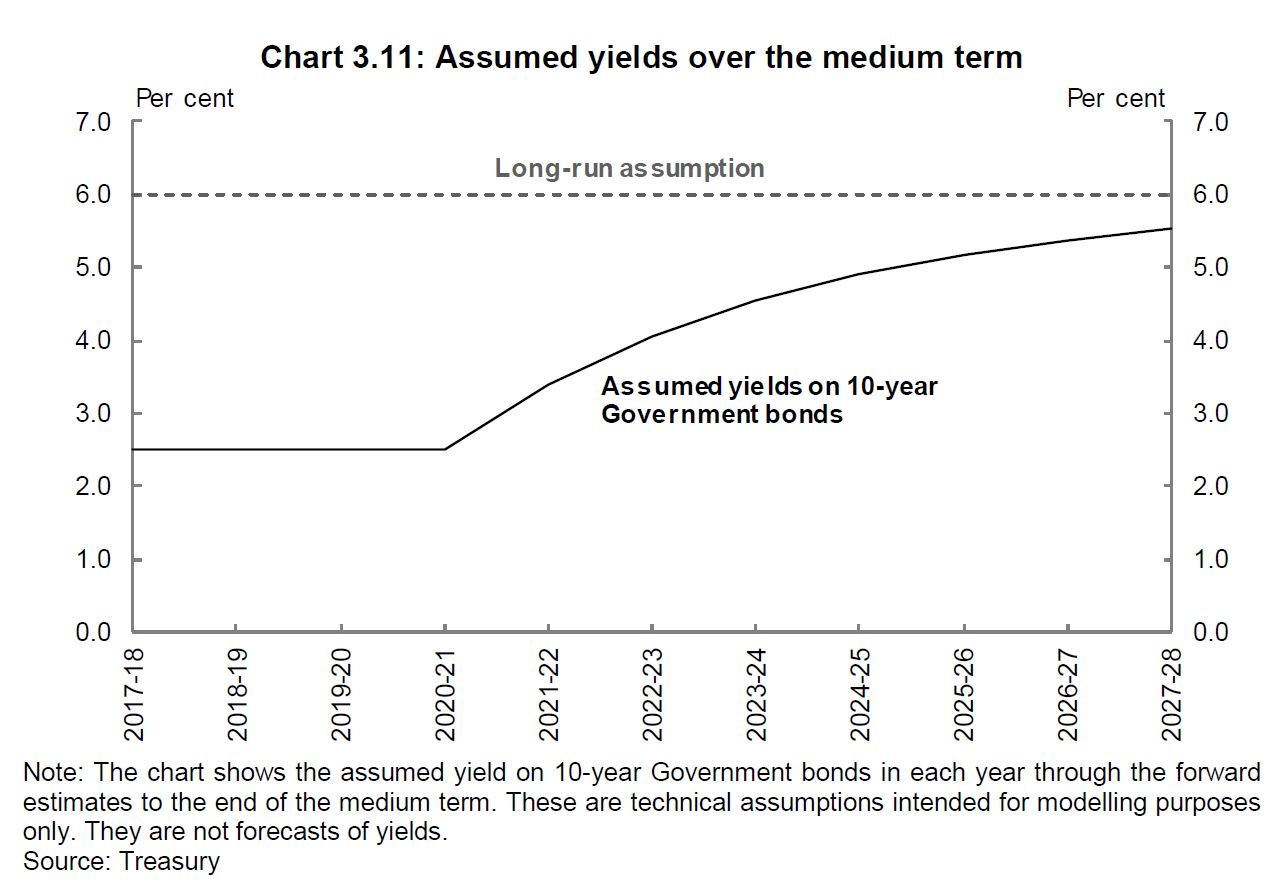

Spending all or most of the extra money that’s pouring into the Treasury coffers risks creating a budget black hole if the sources of that revenue prove to be temporary.

A slowdown in Australia or a drop in China’s demand for raw materials could take a big chunk out of the budget.

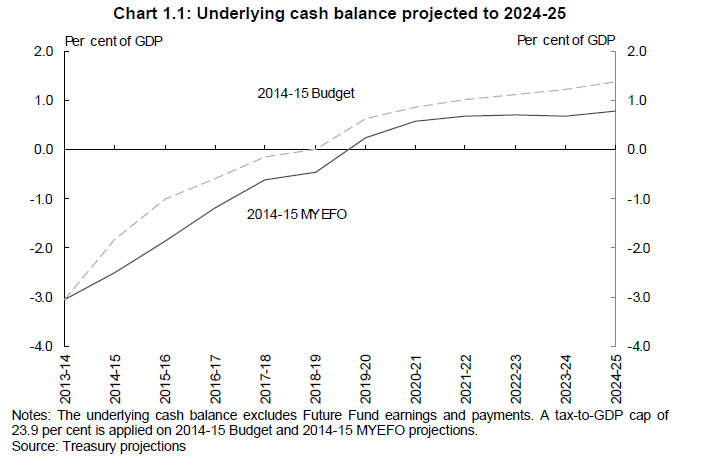

The damage to the government’s finances after the global financial crisis was only partly the result of spending aimed at averting a recession.

We now know a big part of the surge in revenues in the years before the crisis were temporary.

The increased spending and repeated lower taxes they funded were permanent, creating a structural budget deficit that has taken a decade to repair.

As mentioned, the latest upside surprises on revenue are largely due to strong commodity prices and a rising tax take from mining companies.

They might vanish as quickly as they appeared.

Commodity prices are notoriously volatile and almost entirely dependent on what is happening in China.

Problem: China

Perversely, China is buying more of our commodities because it has upped spending on infrastructure to boost a slowing economy under threat of trade war.

The boost in infrastructure spending won’t last.

Eventually we will see a shift in the drivers of Chinese growth towards domestic consumption and business investment and away from metal-intensive infrastructure spending.

It will curtail the growth of our exports and weaken our corporate income tax take.

Dark clouds are forming at home as well.

Problem: Australia

Bank profitability has stopped growing, and the indications from the Hayne Royal Commission are that bank profits will be challenged over the next few years as remediation costs rise and lending slows.

And then there is housing.

While not a direct source of revenue for the federal government, the fall in house prices could start to bite into economic activity as early as next year.

While consumers have so far looked past the lower house values, that is likely to change in 2019 if prices continue to fall.

It’d be wise to hang on to the extra billions

The best economic approach would be for this government to save money and leave it for the next government to use them prudently as needed.

It’s certainly not going to happen.

Centre right governments tend to characterise unexpected bumps in revenue as belonging to the citizenry and to be given back.

They usually do it in the form of income tax cuts. We should prepare for substantial fresh income tax cuts, from as soon as July 1, 2019.

Control of the Treasury is one of the most important weapons available to a political party contesting an election.

Having a prime minister who spent several years as treasurer only enhances the weapon.

The government’s timeline for MYEFO and the April budget suggests they fully intend to use it.

Author: Warren Hogan , Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney