The latest Financial Stability Review from the RBA has a different tone to it, compared with previous edition, because whereas they have previously played up the “cushion” some households have by paying their mortgages ahead, now they say one third of households have no buffer and are exposed to potential interest rate rises. What has changed is not the underlying data, but how it is being presented. Here are some key extracts.

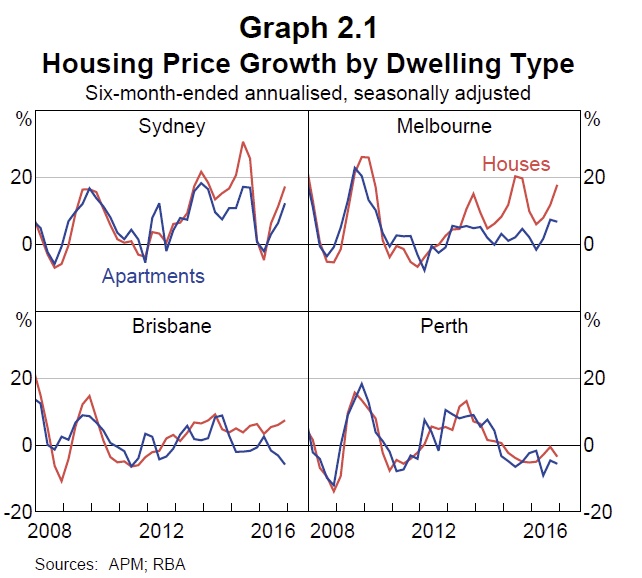

In Australia, vulnerabilities related to household debt and the housing market more generally have increased, though the nature of the risks differs across the country. Household indebtedness has continued to rise and some riskier types of borrowing, such as interest-only lending, remain prevalent. Investor activity and housing price growth have picked up strongly in Sydney and Melbourne. A large pipeline of new supply is weighing on apartment prices and rents in Brisbane, while housing market conditions remain weak in Perth.

Nonetheless, indicators of household financial stress currently remain contained and low interest rates are supporting households’ ability to service their debt and build repayment buffers.

The Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) has been monitoring and evaluating the risks to household balance sheets, focusing in particular on interest-only and high loan-to‑valuation lending, investor credit growth and lending standards. In an environment of heightened risks, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has recently taken additional supervisory measures to reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission has also announced further steps to ensure that interest-only loans are appropriate for borrowers’ circumstances and that remediation can be provided to borrowers who suffer financial distress as a consequence of past poor lending practices. The CFR will continue to monitor developments carefully and consider further measures if necessary.

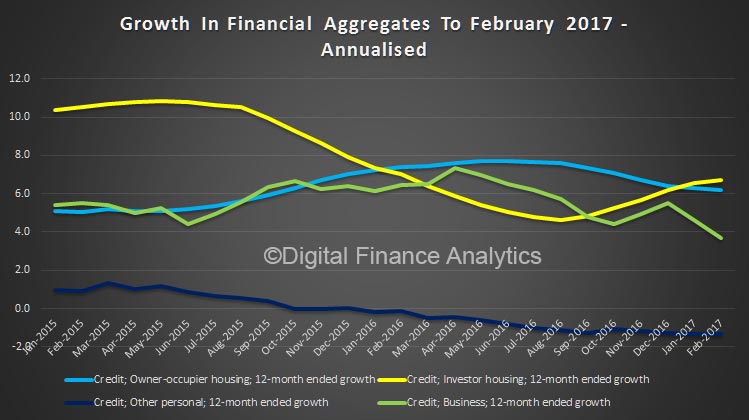

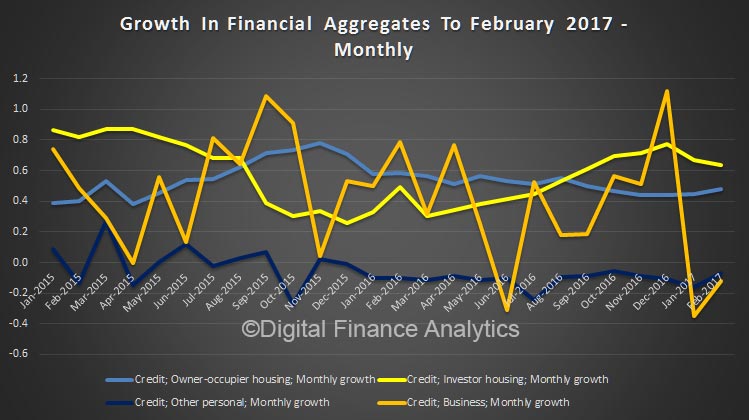

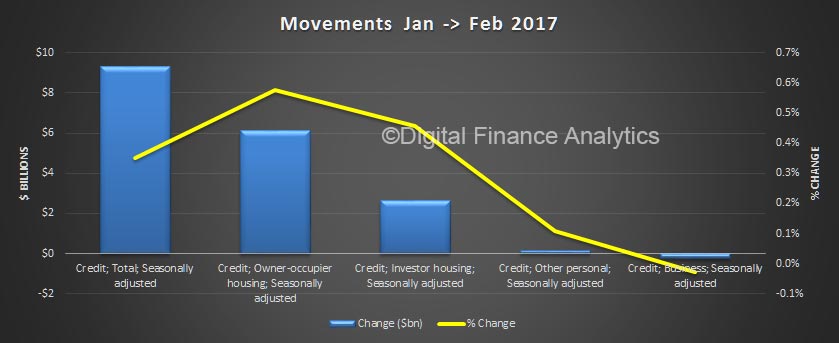

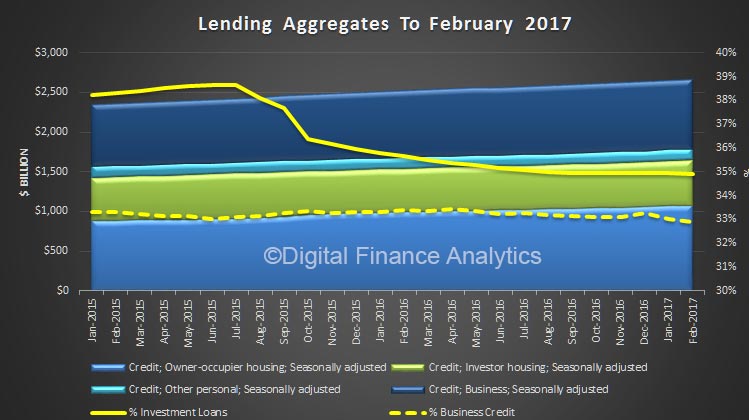

Investor credit has also risen noticeably over the past six months, with investor demand particularly strong in Sydney and Melbourne (Graph 2.3).

Overall household indebtedness has increased while income growth has remained weak. Some types of higher-risk mortgage lending, such as IO loans, also remain prevalent and have increased of late.

The risks associated with strong investor credit growth and increased household indebtedness are primarily macroeconomic in nature rather than direct risks to the stability of financial institutions. Indeed, some evidence suggests that investor housing debt has historically performed better than owner-occupier housing debt in Australia, though this has not been tested in a severe downturn. Rather, the concern is that investors are likely to contribute to the amplification of the cycles in borrowing and housing prices, generating additional risks to the future health of the economy. Periods of rapidly rising prices can create the expectation of further price rises, drawing more households into the market, increasing the willingness to pay more for a given property, and leading to an overall increase in household indebtedness. While it is not possible to know what level of overall household indebtedness is sustainable, a highly indebted household sector is likely to be more sensitive to declines in income and wealth and may respond by reducing consumption sharply.

A further risk during periods of strong price growth is that it may be accompanied by an increase in construction that could result in a future overhang of supply for some types of properties or in some locations. In this environment, as well as amplifying the upswing for such properties, any subsequent downswing is likely to be larger and more likely to see prices and rents fall if the vacancy rate rises. This poses risks to the whole housing market and household sector, not just to the recent investors.

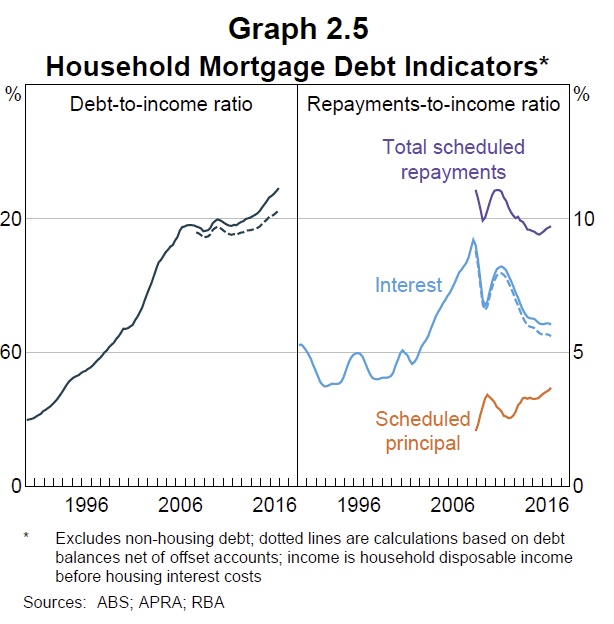

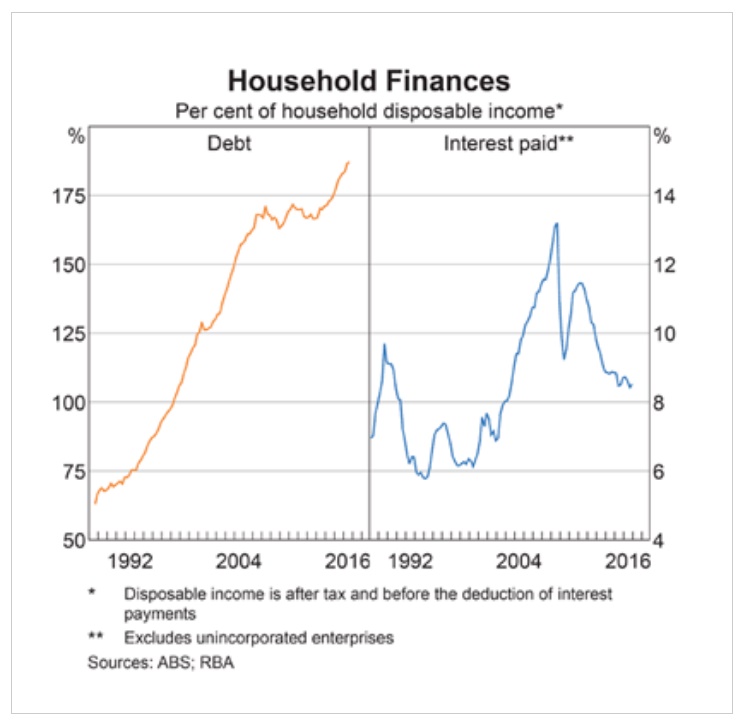

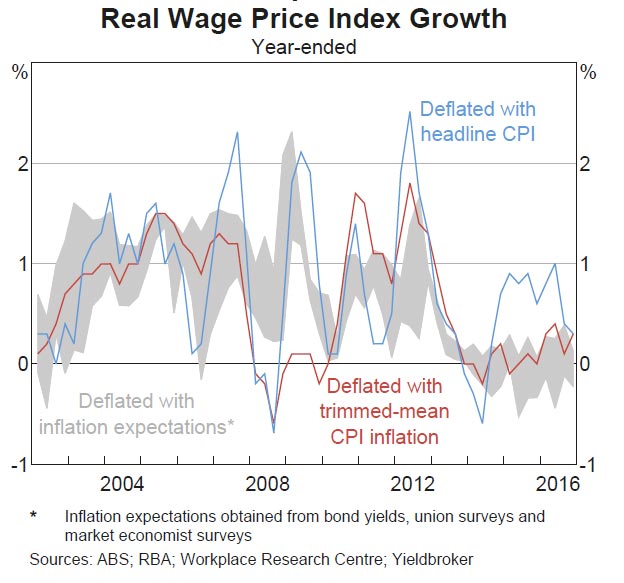

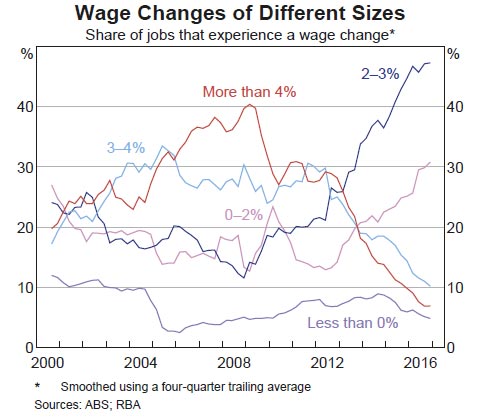

While the financial position of households has been fairly resilient, vulnerabilities persist for some highly indebted households, especially those located in the resource-rich states. Household indebtedness (as measured by the ratio of debt to disposable income) has increased further, primarily due to rising levels of housing debt, although weak income growth is also contributing. Rising indebtedness can make households more vulnerable to potential income declines and higher interest rates. This is of most concern for households that have very high levels of debt.

Low interest rates are helping to offset the cost of servicing larger amounts of debt and hence total mortgage servicing costs remain around their recent lows (Graph 2.5). In this regard, lenders have tightened mortgage serviceability assessments in recent years to include larger interest rate buffers, which should provide some protection against the potential effects of higher interest rates.

Prepayments on mortgages increase the resilience of household balance sheets. Aggregate mortgage buffers – balances in offset accounts and redraw facilities – are high, at around 17 per cent of outstanding loan balances or around 2½ years of scheduled repayments at current interest rates. However, these aggregate figures mask significant variation across borrowers, with available data suggesting that around one-third of borrowers have either no accrued buffer or a buffer of less than one month’s repayments. Those with minimal buffers tend to have newer mortgages, or to be lower-income or lower-wealth households.

Interest-only (IO) loans account for a sizeable and growing share of total housing credit in Australia, now representing around 23 per cent of owner‑occupier lending and 64 per cent of investor lending (Graph B1). IO lending has the potential to increase households’ vulnerability in part due to the higher average level of indebtedness over the life of an IO loan compared with a regular principal-and-interest (P&I) loan.

For some time regulators have highlighted the potential risks associated with IO compared with P&I loans. Because IO loans allow borrowers to remain more indebted for longer, there may be greater credit risks associated with such loans. When loan balances stay high, there is an increased risk of borrowers falling into negative equity should housing prices decline.

Another risk is that borrowers may find it difficult to service higher required payments at the end of the IO period, which increases the chance of default. For example, repayments on a $400 000 loan with a 4 per cent interest rate and a five-year IO period would typically increase by around 60 per cent at the end of the IO period. While some borrowers may have planned to refinance into another IO loan at the end of the IO period, this may be difficult if circumstances have changed.

Borrowers who anticipate future price rises can use IO loans to maintain a higher level of leverage for a given servicing payment, thereby magnifying their returns from rising housing prices but also magnifying any losses. More generally, at an aggregate level this behaviour could induce a more pronounced cycle in housing prices than would otherwise occur, amplifying the size of any subsequent downswing in housing prices.