International Economic Conditions

Members noted that growth of Australia’s major trading partners had eased a little in the early months of 2015, but was forecast to remain close to its long-run average in 2015 and 2016. Minor revisions to the outlook largely reflected weaker growth in China in the March quarter, which had also been reflected in lower bulk commodity prices and hence a slightly lower terms of trade than previously forecast by staff. Monetary conditions remained very accommodative across the globe and low oil prices were also supporting growth of Australia’s trading partners. Core inflation rates were below central banks’ targets in many economies.

Economic growth in China had eased further in the March quarter across a broad range of indicators. The Chinese property market had continued to be a source of weakness in the economy and represented a key source of uncertainty for the outlook, both through the effects on demand for industrial products and on the finances of local governments that relied on land sales to fund infrastructure projects. Members noted that residential property prices had continued to fall, albeit at a more gradual pace, and sales were lower than in the previous year. Chinese demand for steel had eased and had been accompanied by a fall in Chinese iron ore production and relatively flat imports of iron ore, although Australian iron ore exports to China continued to grow. Members noted that the authorities had introduced several measures to address the overhang of housing supply, while the People’s Bank of China (PBC) had lowered the reserve requirement ratio for banks.

Although the prices of iron ore, thermal coal and oil prices had rebounded somewhat from recent lows, members observed that the slowing in the growth of Chinese demand for steel had contributed to declines in the prices of bulk commodities since the start of 2015. As a result, the terms of trade had declined and were expected to continue doing so as lower spot prices gradually fed their way into contract prices for commodities, including liquefied natural gas (LNG). Notwithstanding this, members noted that the forecast terms of trade were considerably higher than they had been prior to the mid 2000s.

Growth in the US economy had moderated in the March quarter, largely reflecting the temporary effects of disruptions related to severe weather and industrial action in West Coast ports. Over the same period, conditions in the labour market had continued to improve. Non-farm payrolls employment had continued to grow strongly over the past six months and the unemployment rate had declined further. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had indicated that it was likely to begin the process of normalising interest rates in the second half of the year as long as economic conditions continued to evolve as expected.

Growth in the Japanese economy looked to have been modest in the March quarter and there were signs that tight labour market conditions were generating stronger wage growth. In the rest of east Asia, growth of both exports and domestic activity appeared to have slowed a little in the March quarter. Economic activity in the euro area had continued to recover gradually over past few months.

Domestic Economic Conditions

Members observed that the forces underpinning developments in the domestic economy were much as they had been for some time. The available data suggested that growth in the domestic economy had continued at a pace a bit below average in the March quarter. Members noted that growth was expected to continue at a similar pace over the coming year before picking up gradually to an above-average pace over the course of 2016/17.

Household consumption growth had picked up late in 2014 and recent indicators were consistent with expectations that consumption would continue to rise gradually, supported by very low interest rates, relatively strong population growth and a gradual decline in the saving ratio. Members noted that if households respond to very low interest rates and higher asset prices to a similar degree as they had in the period prior to the global financial crisis, expected outcomes would include a lower saving ratio and higher consumption growth than embodied in the forecasts. Alternatively, if households were less inclined to bring forward their consumption than had been factored into the forecasts, perhaps to limit the increase in their leverage, consumption growth would be likely to be weaker and the saving ratio higher than forecast.

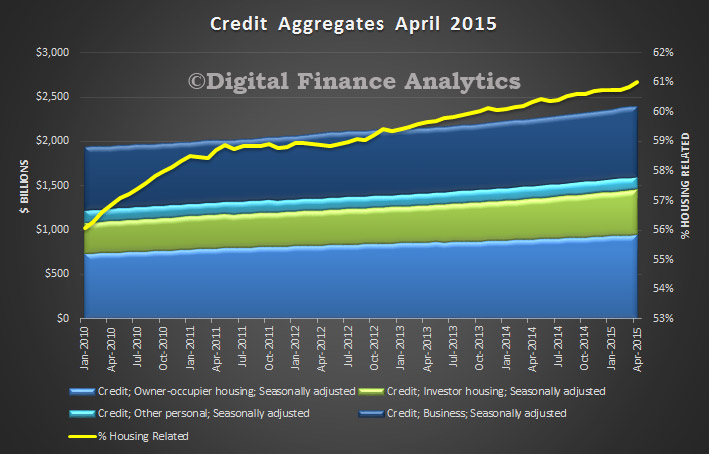

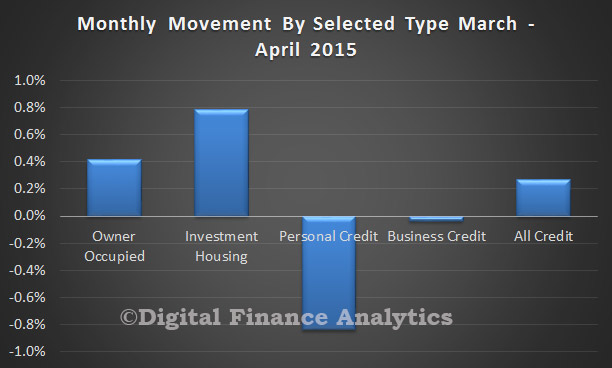

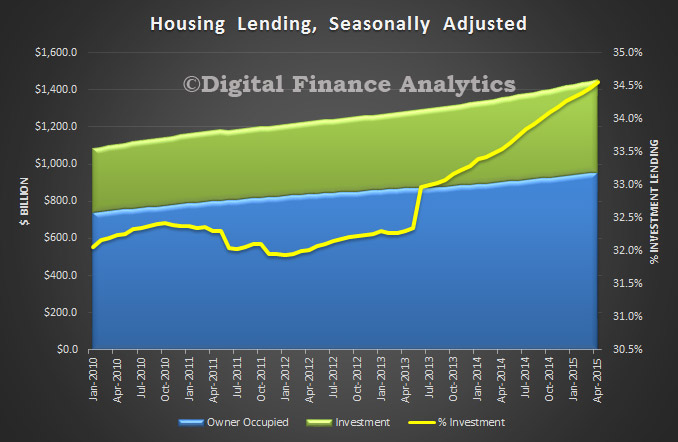

Conditions in the established housing market had remained strong in Sydney and Melbourne. However, across the rest of the country, which accounts for around 60 per cent of Australia’s dwelling stock, housing price growth had declined. The available data suggested that dwelling investment had grown strongly in the March quarter, supported by low interest rates and above-average population growth. Forward-looking indicators, including residential building and loan approvals, suggested that dwelling investment would continue to grow strongly in the next few quarters. Members noted that growth of housing credit for both owner-occupiers and investors had remained relatively stable in recent months, with overall credit growth broadly in line with longer-term income growth.

Survey data had suggested that business conditions in the non-mining sector were around average and that business credit had picked up of late. However, forward-looking measures of business confidence had remained a little below average and non-residential building approvals had also been running at a relatively low level. Members noted that non-mining business investment was expected to recover later than had been thought at the time the forecasts for the February Statement on Monetary Policy had been prepared. This reassessment was consistent with the weak reading on investment intentions for 2015/16 from the December quarter ABS capital expenditure survey as well as business liaison by the Bank, which had suggested for some time that businesses would commit to increasing investment only after observing a durable improvement in the growth of demand. Members noted that exchange rate developments were also likely to remain important for investment decisions. Uncertainty about both the timing and speed of the recovery in non-mining business investment remained key risks to the forecasts. Mining investment was still expected to decline sharply, but the speed of that decline continued to be uncertain.

Resource export volumes had grown strongly in the March quarter, in part reflecting the absence of substantial weather-related disruptions across the country. Resource exports were expected to continue making a strong contribution to growth as new production, particularly of LNG, came on line over 2015. Members noted that the capacity to maintain production plans in the face of lower commodity prices had been enhanced by further cost-cutting by producers, and that this had been assisted by the decline in the price of oil (an input into production) over the past year.

Fiscal consolidation by the federal and state governments was expected to contribute to subdued growth of domestic demand over the forecast period. Members noted that the Commonwealth Budget, which would be announced the following week, would provide important information for updating these forecasts.

The most recent labour force data indicated that employment growth had been increasing over the past six months or more, to be a little above the rate of population growth. Members noted that the revised labour force data also indicated that the unemployment rate had been stable through most of this period at about 6¼ per cent, and observed that the extended period of slow wage growth may help to reconcile these data with the below-trend growth in the economy over 2014. Forward-looking indicators of labour demand had continued to point to modest growth of employment over coming months.

Members noted that the delayed pick-up in GDP growth in the revised outlook meant that the unemployment rate was forecast to rise further, before starting to decline gradually towards the end of the forecast period. Wage growth was not expected to increase from current low levels for some time. Members discussed the possibility that employment growth could grow fast enough such that the unemployment rate did not increase, especially if there was ongoing moderation in wage growth.

Inflation in the March quarter had been broadly as expected. CPI inflation had slowed over the past year, reflecting the large falls in fuel prices and repeal of the carbon price. Underlying inflation had remained around ½–¾ per cent in the quarter and 2¼–2½ per cent over the past year. Domestic inflationary pressures – as indicated by non-tradables inflation – had remained below average, consistent with the extended period of slower wage growth. Inflation in consumer prices related to housing was marginally above its historical average, driven by inflation in new dwelling costs reflecting the strength of the housing market. Tradables inflation (excluding volatile items and tobacco) had picked up in response to the depreciation of the Australian dollar over the past year or so.

Members noted that the inflation forecast had been revised down slightly since February, reflecting the expectation that growth of economic activity would remain below trend for a little longer than previously forecast. Domestic labour cost pressures were expected to remain well contained and underlying inflation was expected to remain consistent with the inflation target over the forecast period. Headline inflation was forecast to remain below 2 per cent in year-ended terms through to mid 2015, before picking up to be consistent with the inflation target thereafter.

Financial Markets

The Board’s discussion of financial markets commenced with the unusual trading in the Australian dollar in the period immediately prior to the announcement of the Board’s decisions in February, March and April. Members were briefed on the Australian Securities and Investment Commission’s preliminary finding, which had been announced the previous day, that each of those moves in the Australian dollar had been a result of ‘normal market operations in an environment of lower liquidity immediately ahead of the RBA announcement’.

Members observed that financial markets continued to focus on the situation in Greece and monetary policy developments in the major economies.

Negotiations between the Greek Government and its official sector creditors remained at an impasse. Greece appeared to have sufficient funds to meet its scheduled payments in May only after the introduction of further stopgap measures. The next Eurogroup meeting was scheduled for 11 May and at least partial agreement would be needed on Greece’s reform agenda before further assistance funds were released. Overall, Greek banks’ reliance on emergency liquidity assistance had increased significantly recently and total Eurosystem lending to Greek banks now exceeded one-quarter of their total liabilities.

Members noted that the apparent deadlock in Greece had had little impact on broader financial markets until recently, when spreads on the debt of other euro area periphery countries – including Portugal and Spain – had increased as concerns surrounding Greek finances continued to rise.

In contrast, yields on German and other highly rated European sovereign debt fell to new lows in April following the continued expansion of the European Central Bank’s balance sheet, with the 10-year Bund yield declining to 8 basis points. In recent days, however, there had been a marked retracement, with 10 year yields rising by more than 30 basis points in Germany and the United States.

In the United States, market pricing continued to suggest that the first increase in the US policy rate could be closer to the end of the year, and the subsequent pace of policy tightening could be slower than that envisaged by members of the FOMC as published in mid March.

In China, the PBC had taken steps to boost liquidity by reducing the reserve requirement ratio. This step had partly sought to offset the reduction in liquidity resulting from sales of foreign reserves by the PBC in recent months. Equity prices had continued to record particularly large rises in mainland China, leading to prices more than doubling since mid 2014. Members noted that the rally in the Chinese share market had coincided with rapid growth in retail financial investments funded by debt, which raised concerns about the sustainability of the rise in share prices and the potential effects of any decline.

The appreciation of the US dollar since mid 2014 had continued its modest reversal over the past month, resulting in a depreciation of the US dollar against most currencies. Reflecting that, together with recent domestic data, the Australian dollar had appreciated by 3 per cent against the US dollar and by 2½ per cent on a trade-weighted basis over the past month. Nevertheless, compared with its level in mid 2014, the Australian dollar remained around 17 per cent lower against the US dollar and around 10 per cent lower on a trade-weighted basis. In contrast, the Chinese renminbi had been little changed against the US dollar over the past month and in trade-weighted terms remained around 12 per cent above its level in mid 2014.

Members noted that equity prices in the major developed economy markets had risen during April, with the exception of Europe, where equity prices fell a little after large rises earlier in the year. In Australia, equity prices also recorded a small decline in April, although the resources sector had outperformed, with energy sector share prices rising following an increase in the oil price.

Corporate bond issuance by Australian entities remained robust in both domestic and international markets amid favourable pricing conditions. In the money market, pricing on money market instruments pointed to around an 80 per cent chance of a reduction in the cash rate target at the present meeting.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

Members assessed that the outlook for global economic growth had been revised only marginally lower in the near term and would continue to be supported by stimulatory monetary policies and the low price of oil. They noted that growth appeared to have slowed in China and that the weakness in the Chinese property market continued to represent a significant risk both for Chinese growth and demand for construction-related commodities. Lower growth in the demand for commodities had contributed to the lower prices of Australia’s key commodity exports since the beginning of the year. As a result, Australia’s terms of trade were expected to decline a little more than was forecast three months ago.

In their discussion of the appropriate course for monetary policy, members noted the revised staff forecasts for the domestic economy. Although the recent flow of data had been generally positive, there had also been indications that future capital spending in both the mining and non-mining sectors would be weaker than expected. Overall, compared with the previous set of forecasts, growth was now expected to take longer to strengthen and the unemployment rate was likely to remain elevated for longer. This change, and generally subdued growth of domestic costs, including wages, implied that inflation was expected to be slightly lower than in earlier forecasts though still consistent with the target. On the face of it, this meant that it would be appropriate to consider an easing of monetary policy.

Members also discussed the potential risk that low levels of interest rates could foster imbalances in the housing market. While concerned about the very strong pace of growth of housing prices in Sydney, and observing that conditions in Melbourne were strong, members saw much more muted trends in other capital cities. As at previous meetings, they acknowledged the risks that could accompany a sustained increase in leverage from already high levels, should that occur, and that the expansionary effects of lower interest rates could be less than in the past. On the data available for this meeting, however, it did not appear that the growth of housing credit, either for investment or owner-occupancy purposes, had been increasing over recent months. The Bank would continue to work with other regulators to assess and contain the risks arising from the housing market.

More broadly, members noted that the low levels of interest rates were helping to support demand in the face of a number of persistent headwinds and that a further reduction in the cash rate would provide some additional support to economic activity by reinforcing recent encouraging trends in household demand. In turn, this would support non-mining business investment insofar as demand conditions were the main factor constraining these decisions. Such outcomes would be expected ultimately to lead to stronger labour market conditions. Members also noted that further depreciation of the exchange rate seemed to be both likely and necessary, particularly given the significant declines in key commodity prices, and that such an outcome would help to achieve more balanced growth in the economy and assist with the transition to a lower terms of trade.

Members discussed the timing of any interest rate adjustment. They could see cases both for moving at this meeting or at the subsequent meeting. The latter course would bring the advantage of additional information on the economy, including details of the forthcoming Commonwealth Budget. On the other hand, with the revised staff forecasts scheduled to be released a few days after the meeting, members acknowledged that the challenges of communication might be more effectively met with a reduction in the cash rate at this meeting.

On balance, taking all these factors into account, the Board decided that the best course was to ease monetary policy further at this meeting. Members agreed that, as at the time of the reduction in the cash rate in February, the statement communicating the decision would not contain any guidance on the future path of monetary policy. Members did not see this as limiting the Board’s scope for any action that might be appropriate at future meetings.

The Decision

The Board decided to lower the cash rate by 25 basis points to 2.0 per cent, effective 6 May.