The Official Cash Rate (OCR) has been reduced to 1.5 percent. They signalled risks from China and Australia, and that lower mortgage rates might help household finances and housing.

The Monetary Policy Committee decided a lower OCR is necessary to support the outlook for employment and inflation consistent with its policy remit.

Global economic growth has slowed since mid-2018, easing demand for New Zealand’s goods and services. This lower global growth has prompted foreign central banks to ease their monetary policy stances, supporting growth prospects.

However, there is uncertainty about the global economic outlook. Trade concerns remain, while some other indicators suggest trading-partner growth is stabilising.

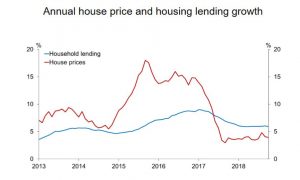

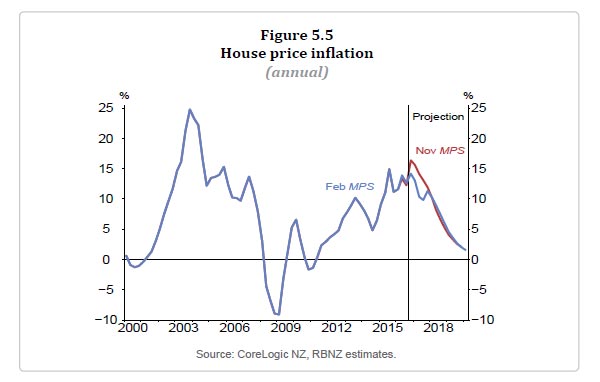

Domestic growth slowed from the second half of 2018. Reduced population growth through lower net immigration, and continuing house price softness in some areas, has tempered the growth in household spending. Ongoing low business sentiment, tighter profit margins, and competition for resources has restrained investment.

Employment is near its maximum sustainable level. However, the outlook for employment growth is more subdued and capacity pressure is expected to ease slightly in 2019. Consequently, inflationary pressure is projected to rise only slowly.

Given this employment and inflation outlook, a lower OCR now is most consistent with achieving our objectives and provides a more balanced outlook for interest rates.

Summary record of meeting – May 2019 Statement

The Monetary Policy Committee agreed on the economic projections outlined in the May 2019 Statement in order to provide a sound basis on which to form its OCR decision.

The Committee noted that inflation is currently slightly below the mid-point of the inflation target, and that employment is broadly at the targeted maximum sustainable level. However, the members agreed that given the recent weaker domestic spending, and projected ongoing growth and employment headwinds, there was a need for further monetary stimulus to meet its objectives.

The Committee agreed that the risks to achieving its consumer price inflation and maximum sustainable employment objectives were broadly balanced around the projection. Possible alternative outcomes were noted on the upside and downside.

A key downside risk relating to the growth projections was a larger than anticipated slowdown in global economic growth, particularly in China and Australia, New Zealand’s largest trading partners. The Committee agreed that the projections adequately captured the observed global slowdown and its impact on domestic employment and inflation.

The Committee noted that additional stimulus from central banks had underpinned growth and reduced the likelihood of a more-pronounced slowdown. With some indicators of global growth improving in recent months, a faster recovery in global growth was possible. However, on balance, the Committee was more concerned about a continued slowdown rather than a faster recovery.

The Committee discussed other potential risks to domestic spending. The members acknowledged the importance of additional spending from households, businesses, and the government, to meet their inflation and employment targets. However, they noted several important uncertainties.

The Committee noted upside and downside risks to the investment outlook. Capacity pressure could see investment increase faster than assumed. On the downside, if sentiment remained low as profitability remains squeezed, investment might not increase as anticipated over the medium term. It was also noted that firms’ ability to invest is constrained by the current competition for resources.

A potential source of additional demand discussed by the Committee included government spending being higher than currently projected, in view of the current strength of the Crown balance sheet. This view was balanced by the impact of any increase in government investment being delayed, for example due to timing of the implementation of new initiatives and current capacity constraints in the construction sector. The implications for monetary policy remain to be seen.

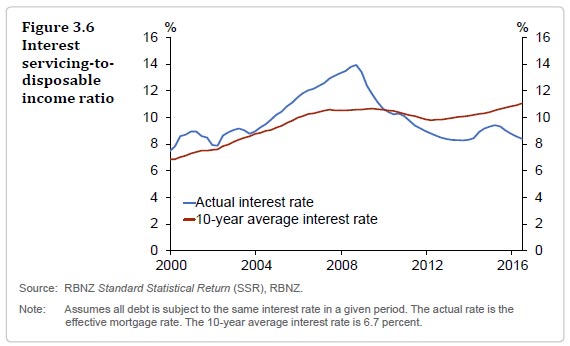

Some members noted that with lower mortgage rates and easing of loan-to-value requirements, any possible pick-up in the housing market could support household spending growth more than anticipated.

The Committee noted that employment is currently near its maximum sustainable level. However, it was agreed that the outlook for employment growth is more subdued and capacity pressure is expected to ease slightly in 2019.

The Committee agreed that overall risks to the inflation projection were balanced. The Committee noted the outlook for inflation is below the target mid-point for longer than projected in the February Statement.

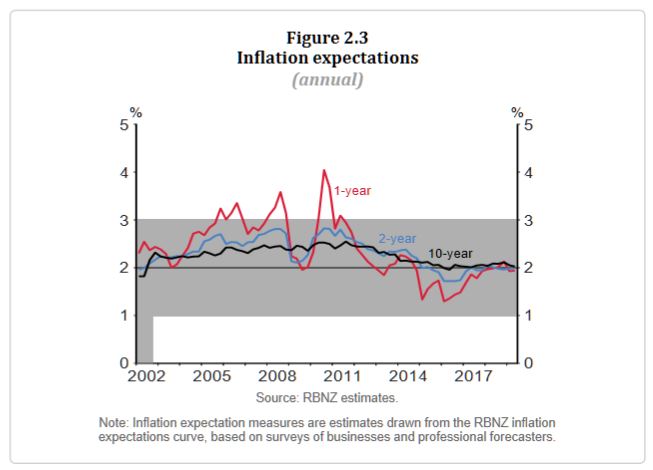

The recent period of rising domestic inflation was discussed. The Committee noted that the near-term outlook was more subdued due to lower capacity pressure. It was also noted that cost pressures remain elevated, and that there is a risk firms may pass these costs on as higher consumer prices by more than assumed. However, it was agreed that inflation expectations remain well anchored at the mid-point of the target range.

The Committee also noted the relatively subdued private sector wage growth, despite businesses suggesting that the inability to find labour is a significant constraint on their growth. The Committee noted the limited pass-through of the nominal wage growth to consumer price inflation.

Some members noted slower global growth reducing imported inflation was a downside risk to the inflation outlook.

The Committee reached a consensus that, relative to the February Statement, a lower path for the OCR over the projection period was appropriate. The lower path reflected the economic projections and the balance of risks discussed, and is consistent with both inflation and employment remaining near the Committee’s objectives.

After discussing the relative benefits of holding the OCR and committing to a downward bias, versus cutting the OCR now so as to establish a more balanced outlook for interest rates, the Committee reached a consensus to cut the OCR to 1.50 percent.