The NZ Reserve Bank confirmed that at this stage some further monetary policy easing is likely to be required to maintain New Zealand’s economic growth around its potential, and return CPI inflation to its medium-term target level.

Further exchange rate depreciation is necessary, given the weakness in export commodity prices and the projected deterioration in the country’s net external liabilities over the next two years, Governor Graeme Wheeler said.

Speaking to an ExportNZ/Tauranga Chamber of Commerce audience, Mr Wheeler said that in mid-2014, New Zealand’s terms of trade were at a 40-year high, but over the past 15 months the economy has experienced several shocks. Export prices for whole milk powder have fallen 63 percent since February 2014, and oil prices are currently more than 50 percent below their June 2014 level. Net immigration and labour force participation are at historic highs, and the real exchange rate has declined steadily since April 2015.

Over the past two years, annual CPI inflation has been in the lower half of the 1 to 3 percent target band, except for the period since the December quarter 2014 when the fall in oil prices brought CPI inflation to very low levels. The Bank expects annual CPI inflation to be close to the midpoint of the 1 to 3 percent target range by the first half of 2016.

“Under the Bank’s flexible inflation targeting framework, the Policy Targets Agreement specifically recognises that annual CPI inflation will fluctuate around the medium-term trend due to factors such as exceptional movements in commodity prices – like those experienced since mid-2014,” Mr Wheeler said.

“There are, however, several risks and uncertainties around the inflation outlook. These include the future path of the exchange rate, which will be influenced by future commodity prices, and the speed with which the recent depreciation feeds through to higher inflation.”

Mr Wheeler said that, despite recent declines, the exchange rate remains above the level consistent with current economic conditions.

“At current levels of export prices, a more substantial exchange rate depreciation will be required to stabilise the net external liabilities position relative to GDP.”

Mr Wheeler added that there is potential for further downward pressure on global dairy prices. “Also, over coming months, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England are likely to begin the process of normalising their interest rates, which could assist our currency lower.”

Turning to interest rates, Mr Wheeler said that current monetary policy settings are providing stimulus to the economy at a time when output looks to be growing around 2.5 percent, slightly below potential, and core inflation remains a bit below the mid-point.

He said that some local commentators have predicted large declines in interest rates over coming months that could only be consistent with the economy moving into recession. “We will review our growth forecasts in the September Monetary Policy Statement but, at this point, we believe that several factors are supporting economic growth. These include the easing in monetary conditions, continued high levels of migration and labour force participation, ongoing growth in construction, and continued strength in the services sector.”

Mr Wheeler said that, in returning inflation to the mid-point of the target band, the Bank has to avoid unnecessary volatility in output, interest rates, and the exchange rate.

“Our judgement in the current circumstances is that aiming to return inflation to around its medium-term target level in about nine to 12 months’ time is an appropriate speed of adjustment. This may not always be the appropriate speed of adjustment. Nor does it mean that the Bank will necessarily deliver a precise outcome as the economy is constantly experiencing shocks and disturbances that policy may need to counter or accommodate.

“Having the scope to amend policy settings, however, is a key strength of the monetary policy regime. In response to these developments, the Bank will review and, if necessary, revise its policy settings to meet its price stability objective. The time path of inflation may change as monetary policy is recalibrated, but the overall goal of meeting the specifications of the PTA will remain the central focus of policy.”

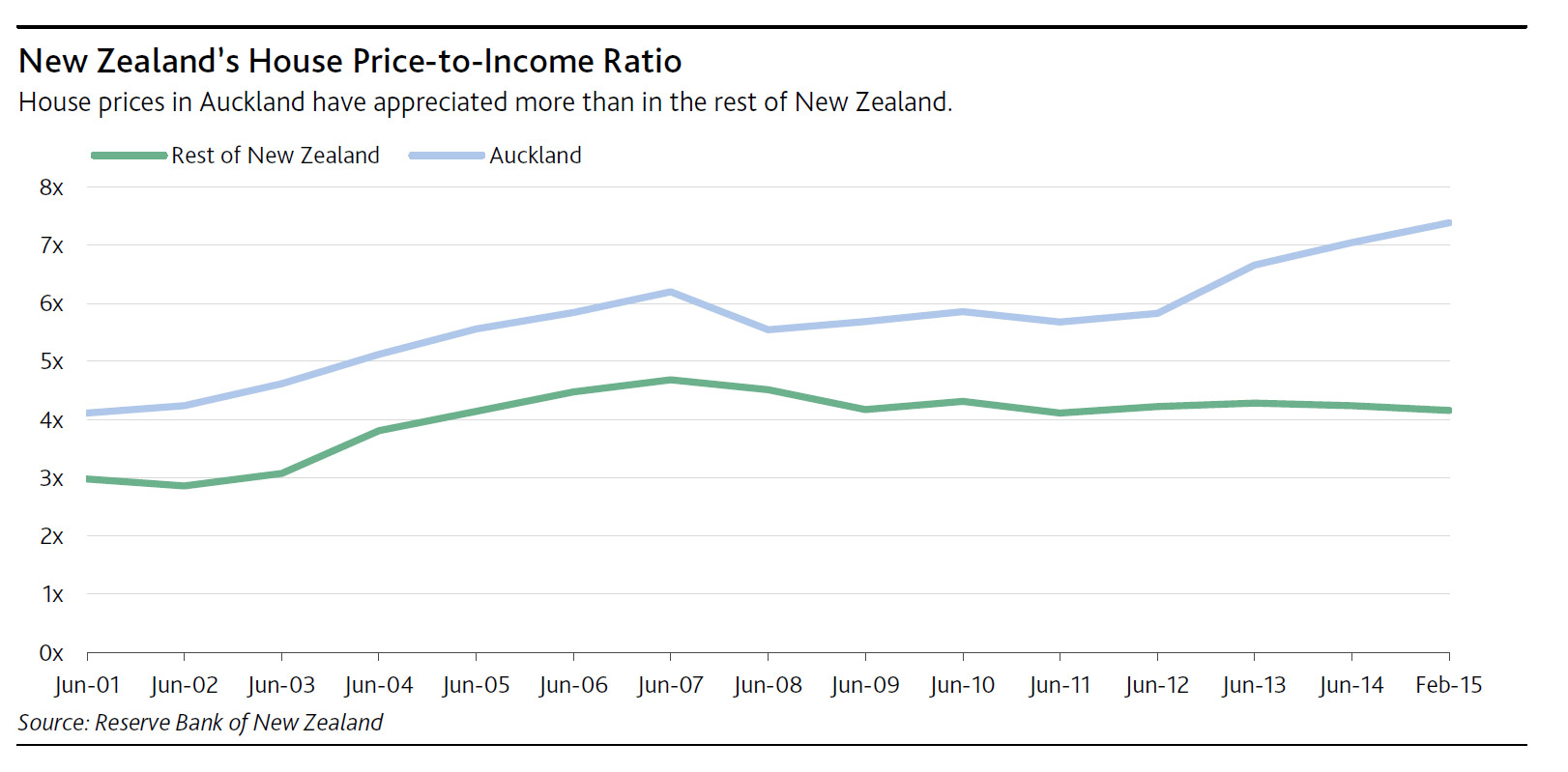

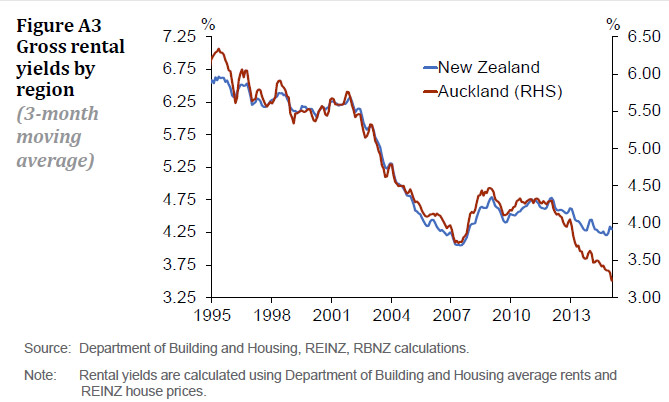

Mr Wheeler also noted that the Bank is conscious of the impact that low interest rates can have on housing demand and its potential to feed into higher house price inflation. Lower interest rates risked exacerbating the already extensive housing pressures in Auckland by stimulating housing demand, although, outside of Auckland, nationwide house price inflation is currently running at an annual rate of around 2 percent. However, in the present situation, raising interest rates would be inappropriate as it would put upward pressure on the exchange rate and further dampen CPI inflation.

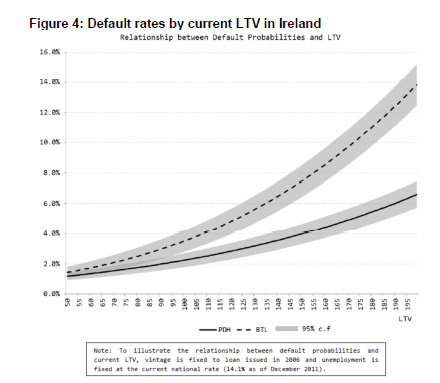

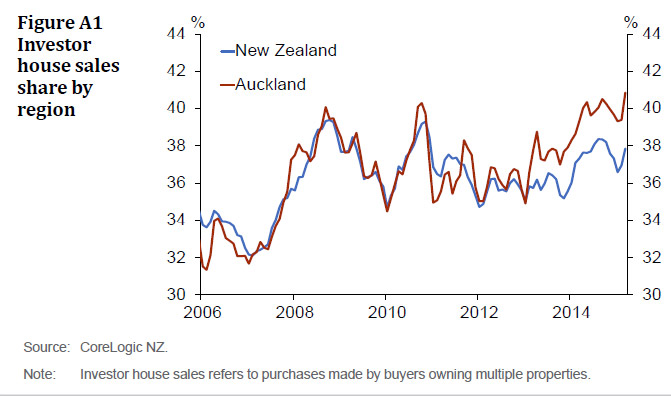

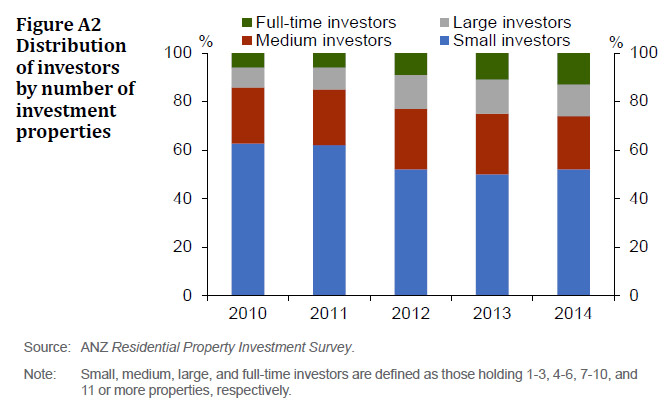

“The Bank continues to be concerned about the financial stability risks and risks to the broader economy that would be associated with a major correction in Auckland house prices. In the current circumstances, macro prudential policy can be helpful in reducing some of the pressures arising from the Auckland housing market. The proposed LVR measures and the Government’s policy initiatives that it announced in the 2015 Budget should begin to ease the impact of investor activity.

“While a strong supply response over several years is needed to address Auckland’s housing imbalance, macro-prudential policy can help to lower the financial and economic risks while important regulatory and infrastructure issues are addressed and additional investment in new housing takes place.”