While all workers benefit from the 9% superannuation guarantee, those on middle incomes benefit significantly less than lower and upper incomes, according to my research.

I ran simulations on the financial assets accumulated over a working life, comparing this to what would have been earned on the same amount saved but invested outside the superannuation system and earning the same rate of return. I’ve added back the last few words here as this is an important assumption in my analysis

People on low, middle and high incomes are all better off under the superannuation guarantee levy. This is due largely to the concessional tax rate (a flat 15%) on income earned in the super fund.

But lower income earners see a lifetime gain 9% higher than for the medium earner. The high income earners receive a gain 8% greater than those on medium incomes.

Ghosts in the system

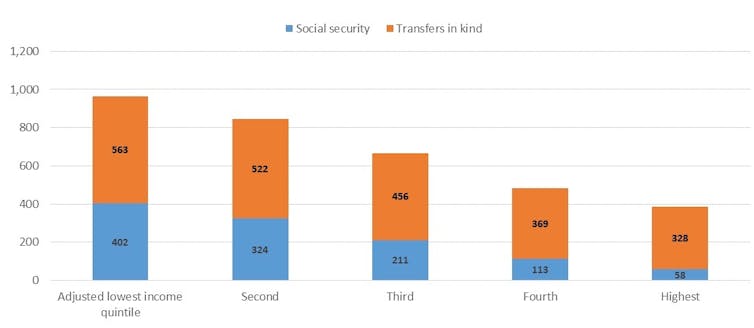

About 80% of Australian government spending on cash benefits to individuals and families is subject to means-testing. This includes the low income superannuation tax offset (LISTO), as well as unemployment benefits, pensions and family tax benefits.

LISTO provides a refund of the 15% tax paid on the super contributions. It is a way of compensating low earners for the greater sacrifice they make in forgoing current spending in favour of superannuation saving.

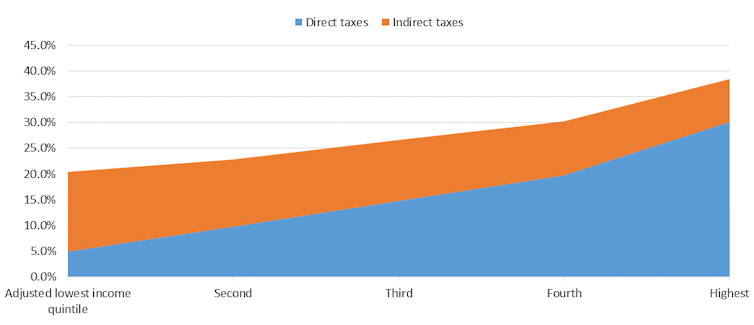

However, means-testing of the LISTO and other cash benefits is a double-edged sword. It may promote some level of fairness, but it can also discourage work through high effective marginal tax rates.

This is because benefits are phased out or cut completely once income reaches a certain threshold, costing the person a benefit they had been entitled to. This is essentially the same as paying a tax.

Means-testing of the LISTO is one way in which our compulsory superannuation levy (SGL) discriminates against middle income earners. Only employees with a taxable income up to A$37,000 are eligible for the refund and it’s capped at A$500 per year.

The super tax offset is lost once taxable income exceeds A$37,000, creating a jump in the effective marginal tax rate paid. This means, according to my simulations, the superannuation guarantee levy provides significantly greater gains to low income earners than middle earners over a working lifetime.

And there are a lot of low income earners. In 2016, roughly 2.9 million employees (28% of all employees) were eligible for the LISTO. This figure is probably an underestimate, as the ABS data used here refers to cash earnings while LISTO is based on taxable income.

The top 20%, or 2 million earners, also gain more than middle earners from their superannuation. This is due to the flat 15% tax on super fund earnings, which represents a significant drop from the marginal tax rate that the high income earner would pay for equivalent savings outside superannuation.

A person with taxable income over A$180,000 will pay 47 cents in tax for every additional dollar earned over A$180,000. But the tax payable on additional income from superannuation earnings is just 15%. This represents a 32% concession (47% minus 15%).

What we could do differently

There is no reason why the superannuation guarantee levy should discriminate against one income group over another. We already have a public pension scheme to support retirement of low income earners – there is no need for superannuation to do this.

New Zealand’s super system, KiwiSaver, offers a great example. KiwiSaver is an “opt out” model of superannuation. Employees are automatically enrolled when they are first employed but they can choose to withdraw their savings.

And unlike Australia’s superannuation guarantee, KiwiSaver allows members to suspend their contributions for between three months and five years after one year of membership. KiwiSaver funds can also be withdrawn to buy an owner-occupied house, provided certain requirements are met.

The flexibility afforded by KiwiSaver means that low income earners are not forced to save through superannuation. In turn this means there is less reason to have tax concessions like LISTO to compensate low earners.

The absence of means-testing benefits in Kiwisaver also avoids the high effective marginal tax rates that act as a disincentive to earn higher income through employment.

KiwiSaver contributions and returns are taxed the same as other savings. This eliminates the gains to high earners from the concessional rate of tax on super fund earnings enjoyed in Australia.

The combination of these KiwiSaver features is that neither the low or high earners are advantaged relative to middle earners.

This is one of several aspects where the New Zealand system of taxation and government benefits is superior to Australia’s in terms of disincentives and complexity, while still allowing New Zealand to have slightly less inequality than Australia.

Author: Ross Guest, Professor of Economics and National Senior Teaching Fellow, Griffith University