The Australian government touts compulsory income management as a way to stop welfare payments being spent on alcohol, drugs or gambling. Via The Conversation.

The Howard government introduced the BasicsCard more than a decade ago. About 22,500 welfare recipients now use it, mostly in the Northern Territory. Now the Coalition government has big plans for a more versatile Cashless Debit Card, trialled on about 12,700 people in four regional communities in Western Australia, South Australia and Queensland.

These trials aren’t complete, nor the findings compiled, but a string of senior ministers, including Prime Minister Scott Morrison, have indicated they are already sold on expanding the program.

Our research, however, adds to the evidence that compulsory income-management policies do as much harm as good.

Financial (in)stability

Over the past year we have conducted the first independent, multisite study of compulsory income management in Australia. It has involved 114 in-depth interviews at four sites: Playford (BasicsCard) and Ceduna (Cashless Debit Card) in South Australia; Shepparton (BasicsCard) in Victoria; and the Bundaberg and Hervey Bay region (Cashless Debit Card) in Queensland. We also collected 199 survey responses from around Australia.

Proponents of compulsory income management champion its potential to “provide a stabilising factor in the lives of families with regard to financial management and to encourage safe and healthy expenditure of welfare dollars”, as the then social services minister, Paul Fletcher, said in March last year.

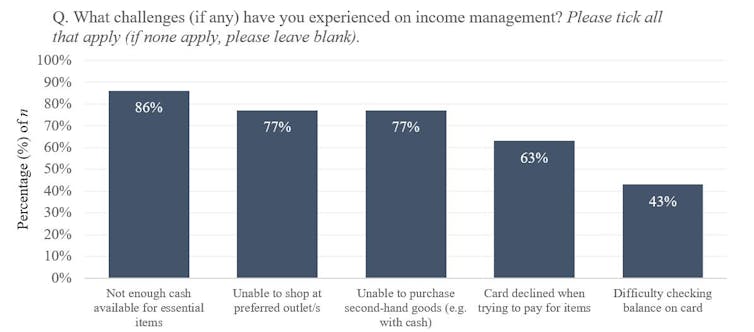

Our study found some individuals experience these benefits. But most face extra financial challenges. These include not having enough cash for essential items, being unable to shop at preferred outlets, being unable to buy second-hand goods, and cards being declined even when they are supposed to work.

In Playford, Jacob* told us about being on the BasicsCard, which can only be used with merchants that have agreed to not allow cardholders to buy excluded goods.

The limits on where he could shop made it harder for him to manage his finances.

“I couldn’t make decisions about saving money,” he told us. He and his wife used to catch the train to shop at the Adelaide markets, for example, but vendors there couldn’t take the BasicsCard.

The Cashless Debit Card is intended to overcome the limitations of the BasicsCard. It’s like a debit card except it can’t be used to withdraw cash or at businesses that sell prohibited items.

But Emma*, a single mother in the Bundaberg and Hervey Bay area, told of her struggles to make basic purchases using the card. It often failed – even at businesses that purportedly accepted it – and her family went without. She also felt excluded from the markets and second-hand retailers where she used to shop.

Her greatest stress, however, was rent. Emma* said she had always been on time with rental payments until the Cashless Debit Card. She described one occasion when, two days after paying the rent, the money “bounced back” into her account. When she rang the card’s administrator (card payment company Indue), she was told: “It’s just a minor teething issue, just keep trying.”

The extra stress from “worrying about which payments were going to get paid” was considerable. Others shared similar experiences.

Social (dis)integration

Supporters of compulsory income management claim it brings people back into the community by combating addiction and encouraging pro-social behaviour and economic contribution. As federal Attorney-General Christian Porter said in 2018: “The cashless debit card can help to stabilise the lives of young people in the new trial locations by limiting spending on alcohol, drugs and gambling and thus improving the chances of young Australians finding employment or successfully completing education or training.”

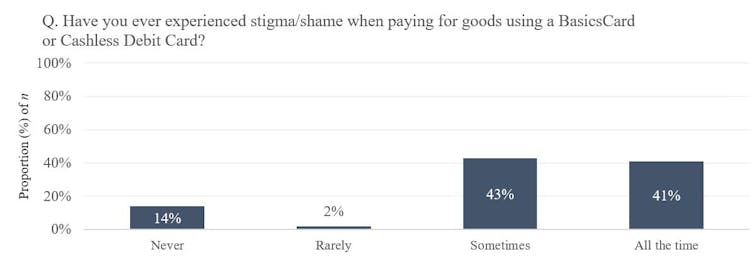

However, our study found the card can also stigmatise and infantilise users – pushing people without these problems further to the margins.

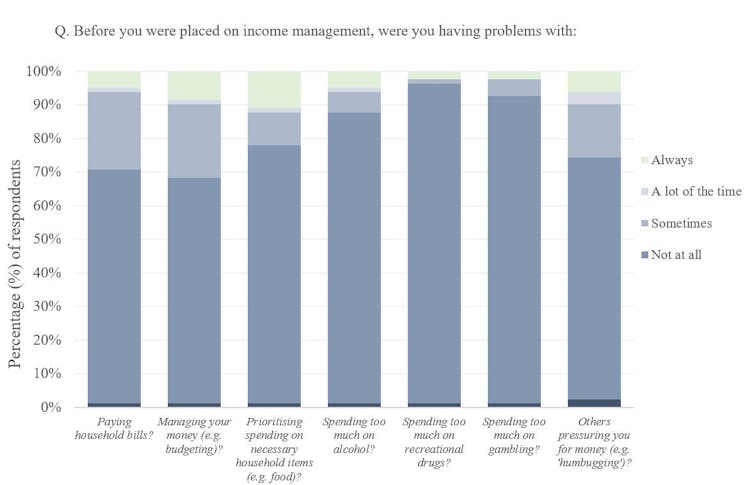

One of the problems is that compulsory income management is routinely applied based on where a person lives and their payment type, and not on any history of problem behaviour. The large majority of our respondents indicated they did not have alcohol, drug or gambling issues.

But as Ray* in Ceduna explained, having the card meant others viewed him as a problem citizen.

I’m embarrassed every time I have to use it at the supermarket, which is about the only place I do use it. I sort of look around and see who’s behind me in the queue. I don’t want anybody to see me using it.

This was a common experience across the interview sites.

Maryanne* in Shepparton told about being judged for shopping for groceries with her BasicsCard.

I got called a junkie and I said: ‘I’m not a junkie, do you see any marks or anything?’ They were like: ‘No, but you have a BasicsCard.’ I said: ‘What’s that got to do with it? Centrelink gave it to me. I can’t do nothing.’

A path forward

The overwhelming finding from our study is that compulsory income management is having a disabling, not an enabling, impact on many users’ lives. As the policy has been extended, more and more Australians with no pre-existing problems have been caught up in its path.

This does not mean a genuine voluntary scheme could not be maintained, but it would need to sit alongside evidence-based measures to tackle poverty.

Addressing the inadequacy of income support payments, ensuring decent employment and training opportunities, and providing accessible social services and secure and affordable housing would be a better starting point for creating healthy lives and flourishing communities.

Names have been changed to protect individuals’ privacy.

Authors: Greg Marston, Head of School, School of Social Science, The University of Queensland; Michelle Peterie, Research Fellow, The University of Queensland; Phillip Mendes, Associate Professor, Director Social Inclusion and Social Policy Research Unit, Monash University; Zoe Staines, Research fellow, The University of Queensland