Following the monumental Conservative election victory, now is the time for the economics to work through. Mark Carney is due to leave his post as governor of the Bank of England at the end of January after six and a half years in charge, and the chancellor, Sajid Javid, will be choosing a replacement soon – perhaps before Christmas. Via the UK Conversation.

This will be a pivotal decision for the chancellor – no doubt in close consultation with Boris Johnson and his advisers. Whoever they pick should not expect a honeymoon period. They are arriving against the backdrop of Brexit, widening regional inequality and the prospect of a downturn in the global economy.

The frontrunners are said to be Minouche Shafik, director of London School of Economics; Kevin Warsh, a former top official at the US Federal Reserve; and Andrew Bailey, chief executive of UK regulator the Financial Conduct Authority. Add to these names Jon Cunliffe and Ben Broadbent, both currently deputy governors at the Bank. Behind this sits a couple of more alternative candidates: Santander chair and former Labour minister Shriti Vadera and Boris Johnson’s former economic adviser, Gerard Lyons.

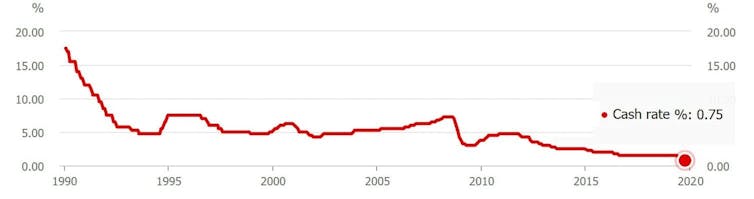

An alternative governor may be just the required medicine at present, since there is a strong case for someone willing to think differently about central bank management. With interest rates still very low in the UK and most other developed economies, there are widespread concerns that central banks will be unable to fight another downturn using the classic response of cutting rates.

Beyond this, there are arguments for revising the entire model of central banking. In recent years, the trend has been for them to manage rates without any political interference and to concentrate purely on keeping inflation low. Indeed, it is almost 30 years to the day since the Reserve Bank of New Zealand became the first central bank to make inflation the sole priority.

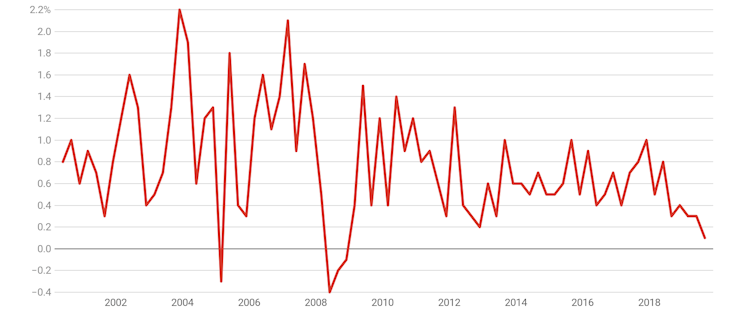

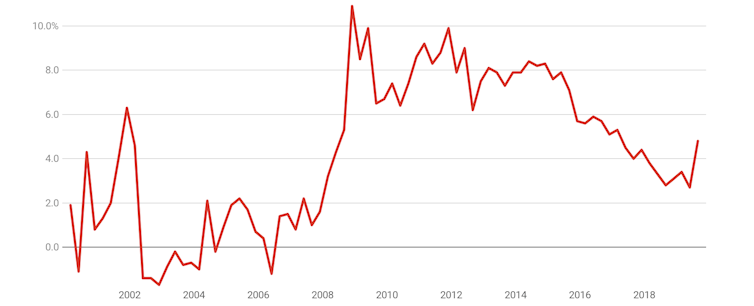

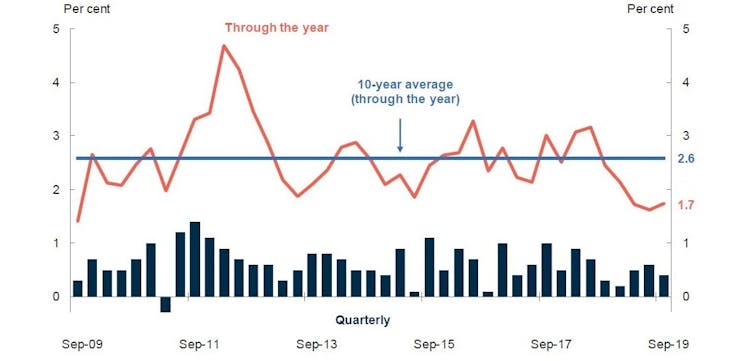

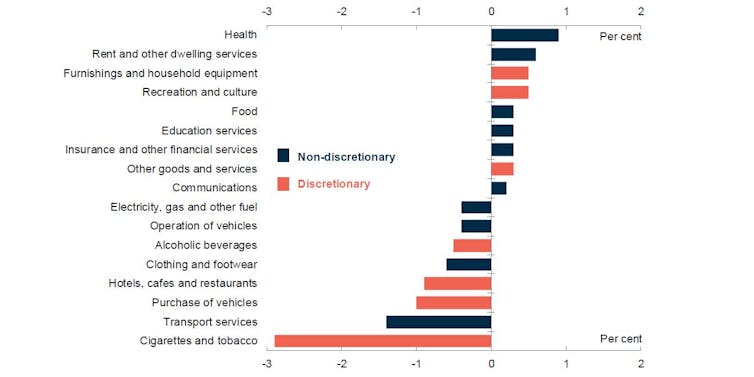

In times of inflation, this system made sense. But since the 2007-08 financial crisis, the world has found itself in a situation where economic growth is much weaker and deflation is more of a risk than inflation.

The Bernanke exception

As former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke said in a speech in Tokyo in 2003, “in the face of inflation … the virtue of an independent central bank is its ability to say ‘no’ to the government”, but with protracted deflation of the kind that has continually dogged Japan, “a more cooperative stance” by central banks towards the government is required.

His argument was essentially that it’s hard to sustain inflation by manipulating interest rates, and that you’re more likely to be successful using the fiscal levers of government spending and tax cutting. The same approach is arguably required in the UK today and across the developed world.

Having lost the ability to properly stimulate the economy using interest rates, the Bank of England and other central banks have taken it in turns to resort to quantitative easing – essentially creating money with which to buy mainly government bonds from banks and other financial institutions. This was supposed to drive extra liquidity into the economy, but mainly it has just been used to bid up prices in the likes of the bond market and stock market and exacerbate the wealth gap.

As an alternative, some commentators are now touting “helicopter money”: this would involve central banks creating money that would be handed straight to the public via government tax cuts or public spending – thus requiring them to coordinate their policies in a way that does not happen at present.

This could be pursued in conjunction with a novel concept called “modern monetary theory”, which envisages government targets to boost demand and inflation financed by a disciplined central bank that keeps interest rates at zero. We are already seeing signs of the government moving in the same direction by shifting away from austerity towards more generous spending.

As for the Bank of England’s own targets, greater policy cooperation with the government would provide wiggle room for focusing beyond inflation. In particular, the Bank could play a role in addressing regional inequality. The UK already has the one of the worst rates of regional inequality in the developed world, with areas like the north of England and West Midlands bringing up the rear. This will be heightened by leaving the EU, since these same areas are key to international supply chains and expected to be the worst hit.

The answer is for the government to pursue an industrial policy that aims to improve productivity in regions where it is weakest, through the likes of targeted tax breaks and economic development zones, with an accommodating Bank of England providing the funding to facilitate.

More productive areas attract more capital, which is the reason behind the north-south divide in the first place. Such an industrial policy would encourage more investment in these areas, produce real-wage increases, boost local demand and stimulate regional development. In short, it would help counteract the impact of Brexit.

Long-term thinking

Two central criteria for the appointment of the next Bank of England governor stand out. First, they must understand the deeper economic and social circumstances that have led to Brexit and the UK’s shift to the right. They must act as governor for the whole country and not just for London plc: a move away from focusing on smoothing short-term fluctuations towards prioritising long-term growth.

Second, the job specification for the next governor says that the candidate should have “acute political sensitivity and awareness”. This might suggest that the government does not want another governor with such outspoken views on say, the economic risks from Brexit. Be that as it may, policy coordination needs to be a priority. I don’t rule out the possibility of the leading candidates being able to work like this, but I worry that they will be too orthodox for the challenge. The government should recognise the shifting sands in central bank policy and appoint someone who is willing to lead from the front.

Author: Drew Woodhouse, Lecturer in Economics, Sheffield Hallam University