As American baseball legend Yogi Berra once supposedly quipped, “It’s déjà vu all over again.” Three years ago the crisis was in Greece, now it’s Turkey. Another European summer and another European economic crisis.

It’s tempting to say that being in Europe is all the two situations have in common. Greece’s population is a little over 10 million; Turkey’s is nearly 80 million. Greece’s troubles were triggered by out-of-control government debt; Turkey’s government debt-to-GDP ratio is quite low. The Greek government was on the loopy left; Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party is on the conservative right.

But the similarities between the Greek and Turkish crises are deeper than the differences.

Both were brought about by decades of ignorant, populist economics. When crisis hit, both countries had leaders who instantly made things worse. And in both cases the world’s global capital capital markets have proved to be an unforgiving judge.

Erdogan’s voodoo economics

Turkey finds itself in crisis not because of massive government debt – although it has been rising pretty rapidly of late and private-sector debt is a real issue – but because of a large current account deficit.

The current account deficit – roughly the difference between the value of what it imports and what it exports – is running at more than US$60 billion at an annualised rate.

This means Turkey is a large net borrower from the rest of the world.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has goosed GDP through cheap foreign credit and low real interest rates. But unlike tinpot strongmen who worry mainly about holding onto power tomorrow, global markets look far into the future.

And this year markets decided that Turkey’s economic future looked pretty bleak.

A plummeting lira

The Turkish currency, the lira, has fallen by more than 40% against the US dollar this year. Since more than half of Turkey’s foreign debt (government plus private) is denominated in foreign currencies, this is a big problem.

It is estimated that there is more than US$200 billion of dollar-denominated Turkish corporate debt. When the lira falls, foreign-denominated debt rises, making it hard to service, let alone repay.

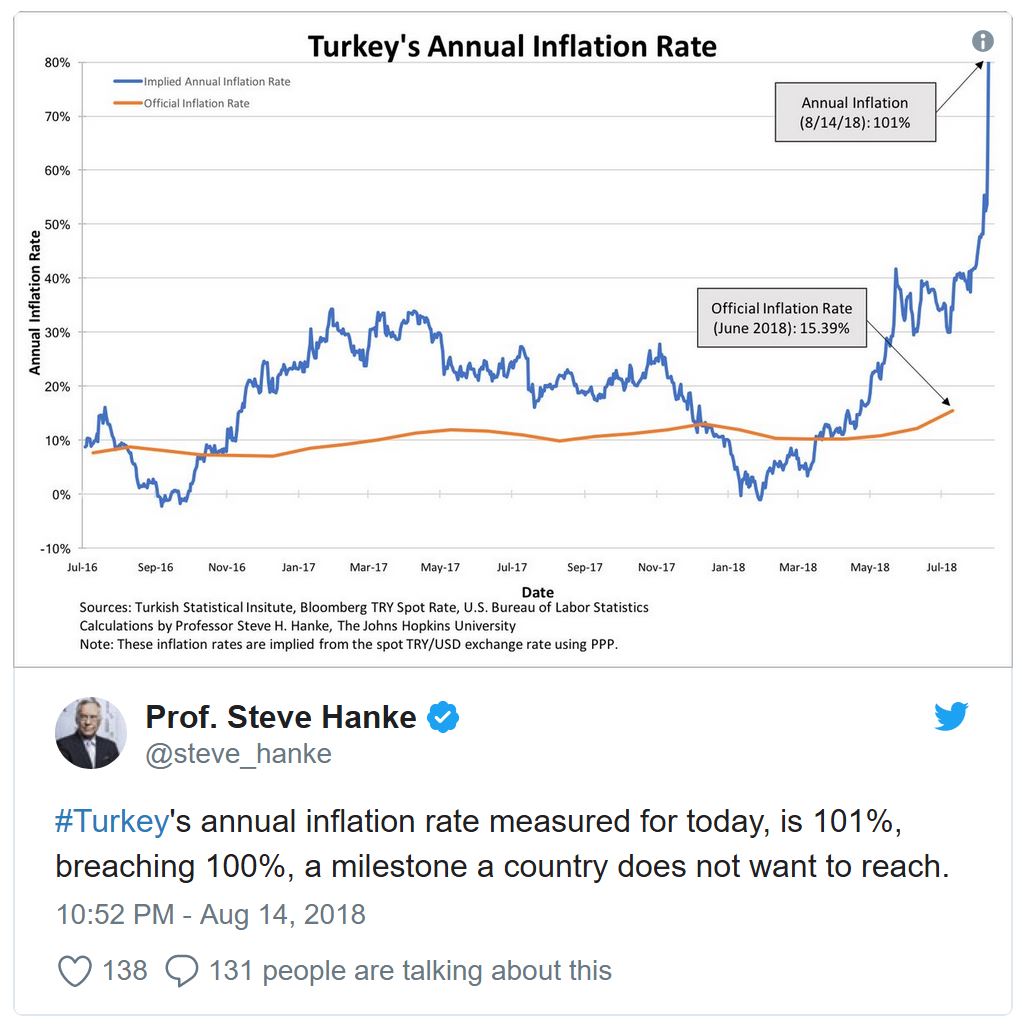

At the same time, the inflationary spiral this sets off does huge damage to the domestic economy. It is estimated that Turkey’s annual inflation rate is running at more than 100%.

Erdogan doesn’t want interest rates to rise – and he has bullied the central bank into doing so later and less than the bank otherwise might have. He is on record as saying that higher interest rates increase inflation, rather than the opposite, as every first-year economics student knows.

To Erdogan, black is white, night is day, up is down.

US President Donald Trump announced last week that “Aluminum will now be 20% and steel 50%. Our relations with Turkey are not good at this time!” Erdogan’s response has been to call for a boycott of iPhones and enact retaliatory tariffs of as much as 140% on a range of US goods.

Erdogan did secure US$15 billion in foreign investment from Qatar, after meeting Emir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Bin Al Thani in Ankara on Wednesday. That might stop some of the bleeding for now, but this gives Qatar tremendous leverage.

The real cost of this support won’t be measured in basis points.

Global contagion?

The big risk here is that the foreign holders of all this dollar-denominated Turkish debt get into trouble as Turkey struggles to repay or defaults. Even the Bank of International Settlements doesn’t easily know who all these debt holders are, but banks in Spain and France appear to be significantly exposed – especially Spain.

A run on the Turkish currency could turn into damage to balance sheets of banks across Europe, triggering a potential debt crisis in countries like Spain.

That’s some distance off for now. But it looms.

All this will likely end in some kind of International Monetary Fund assistance package – but that’s going to come with conditions. Folks who like to use the term “neoliberal” will dub such conditions as brutal austerity.

Others will consider the conditions the cost of stabilising an economy pushed to the brink by a financially illiterate megalomaniac.

Economics in a world of democratic backsliding

Turkey may be at the centre of the crisis du jour, but Erdogan is but one of a cast of nasty, illiberal characters. Although they occupy varying positions on the ideological spectrum, from Poland to Hungary to Latin America, there has been significant democratic backsliding in recent years.

These strongmen do violence to principles of liberal democracy – often literally. They also damage their economies and, as a consequence, their people.

Institutions like the International Monetary Fund will probably handle the problem in Turkey, although it would be a lot simpler if Erdogan just allowed interest rates to increase and solve the problem directly.

But sadly we can expect more illiberal and nonsensical economics from these illiberal strongmen. It is contagious populist ideology more than financial contagion that should scare us right now.

Author: Richard Holden Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW