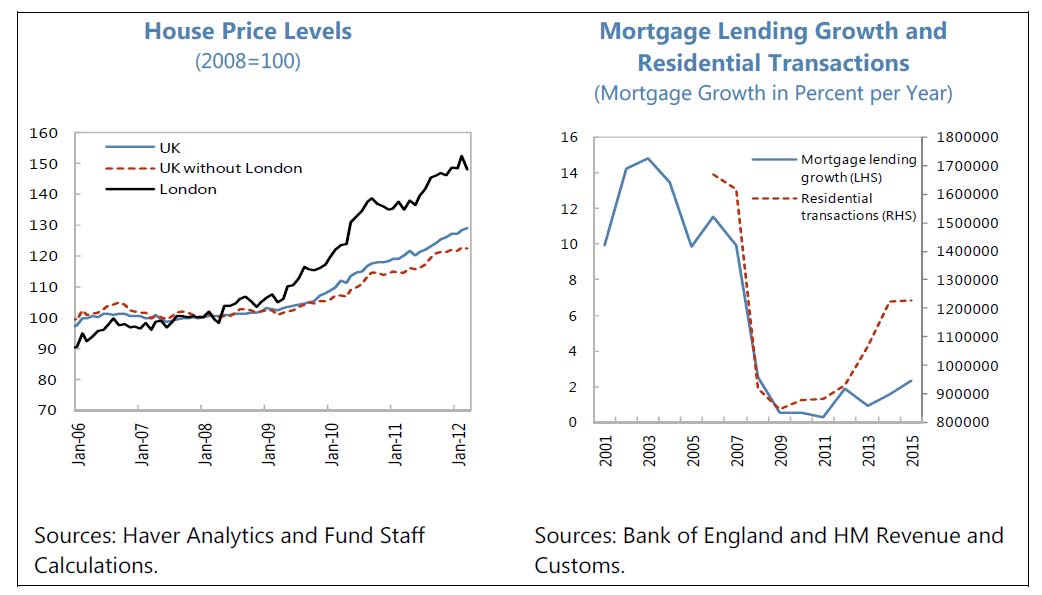

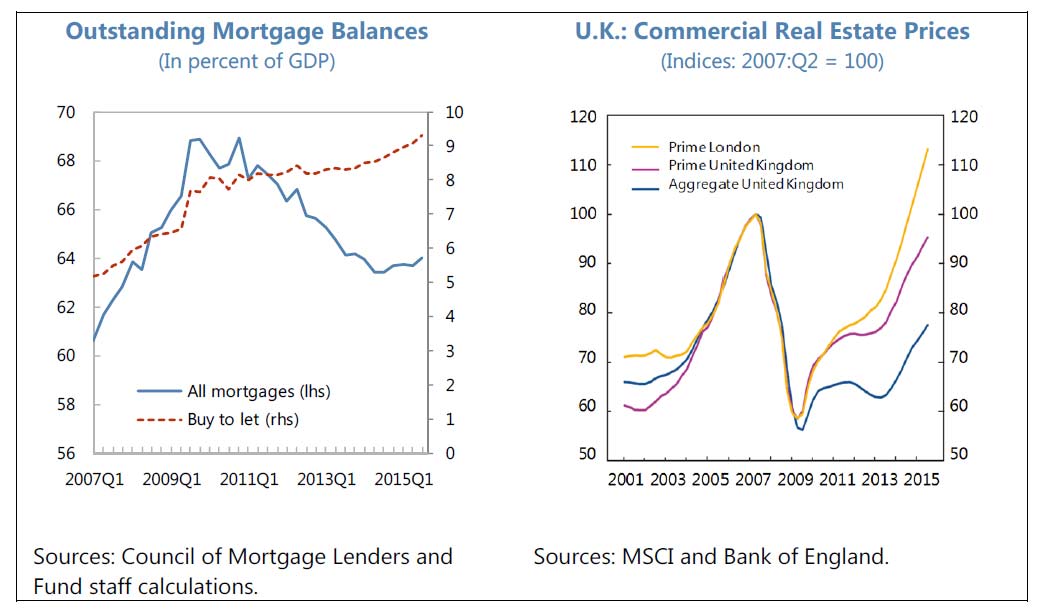

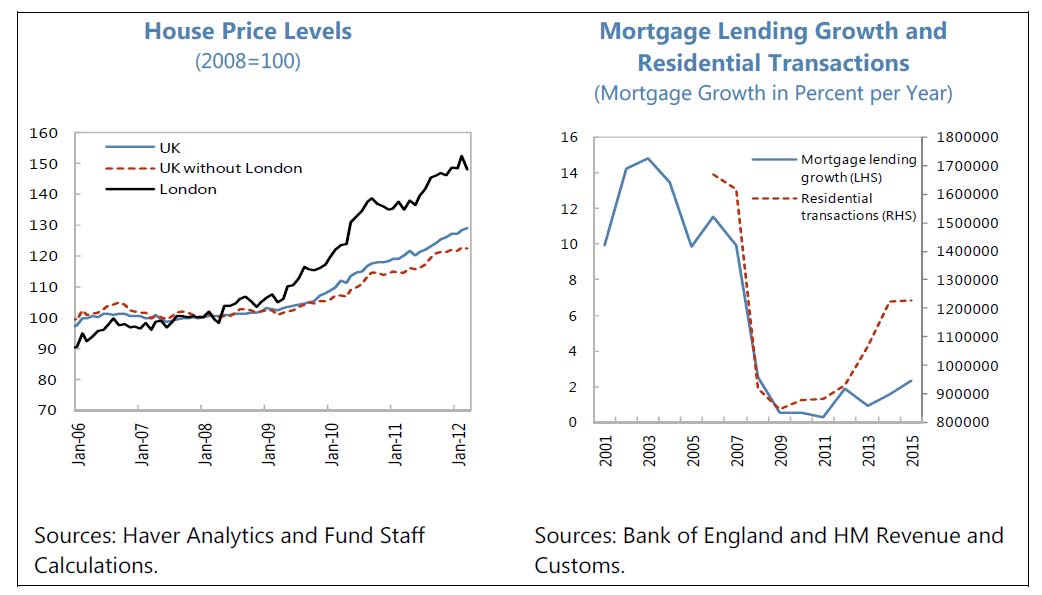

U.K. residential property prices reflect mostly long-standing supply-demand imbalances. While annual house-price growth slowed substantially between mid-2014 and mid-2015, it has accelerated again more recently, outpacing the growth of nominal GDP. This price growth largely reflects the realignment of relative prices of housing in light of tight supply constraints and growing demand. There is little evidence of a credit-fueled boom: the growth of mortgage lending and the number of housing transactions still remain well below their pre-crisis levels. At the same time, two particular segments of the property market show signs of overheating. First, lending in the buy-to-let sector has grown from 4 percent of mortgage stock in 2002 to 16 percent in mid-2015. In view of this, the FPC requested powers of direction over this sector. As the FPC already has these powers over the buy-to-own market, this would level the regulatory playing field for residential mortgages.

At the same time, two particular segments of the property market show signs of overheating. First, lending in the buy-to-let sector has grown from 4 percent of mortgage stock in 2002 to 16 percent in mid-2015. In view of this, the FPC requested powers of direction over this sector. As the FPC already has these powers over the buy-to-own market, this would level the regulatory playing field for residential mortgages.

Since the last FSAP, the U.K. financial system has put the legacy of the crisis behind it and has become stronger and more resilient. Five years ago, the financial system had stabilized but still faced major residual weaknesses. This FSAP found the system to be much stronger and thus better able to serve the real economy. Like all systems, the U.K. financial system is exposed to risks. Given its size, complexity, and global interconnectedness, if these risks were to materialize they could have a major impact not only on the U.K. but also on the global financial system. Financial stability in the U.K. is thus a global public good. At the same time, understanding, mitigating, and staying a step ahead of the evolving risks in such a complex system is a constant analytical and policy challenge for U.K. policy-makers and regulators.

Its position as a global hub exposes the U.K. financial system to global risks. Regardless of the trigger, global shocks, such as a negative growth shock in emerging markets, a rapid hike in global risk premia, or renewed tensions in the eurozone, would impact significantly U.K. banks and, more broadly, the financial system as a whole. Moreover, as the domestic credit cycle matures while interest rates remain at historic lows, trends in some segments of the U.K. property market—notably buy-to-let and commercial real estate—could become financial stability risks.

In addition, the uncertainties associated with the possibility of British exit from the EU weigh heavily on the outlook. A vote in favor of leaving would usher in a period of uncertainty and financial market volatility during the negotiation of the terms of British exit, which could take years. And the eventual exit deal would have profound effects on trade and the real economy, the “passporting” arrangements for financial institutions, and the location decisions of major international financial firms now headquartered in London. Though highly uncertain, these effects would have major long-term implications for the U.K. financial sector, its contribution to the domestic economy, and its global standing. Needless to say, these economic aspects are only one element of the decision that is for British voters to make.

The main parts of the U.K. financial system appear resilient. At the core of the system, banks have more than doubled their risk-weighted capital ratios from pre-crisis levels, strengthened liquidity, and reduced leverage. Stress tests by both the BoE and the FSAP show that the largest banks would be able to meet regulatory requirements and sustain the capacity to finance the economy in the face of severe shocks. The possible impact of Brexit, however, though potentially significant, is inherently difficult to quantify and has not been covered in the stress tests. U.K. insurers, asset managers, and central counterparties (CCPs) also appear resilient, based on assessments by the BoE, FCA, European financial authorities, and the FSAP.

Despite the apparent resilience of individual sectors, interconnectedness across sectors has the potential to amplify shocks and turn sector-specific distress systemic. New patterns of interconnectedness are emerging due to structural market shifts and new entrants in some markets. These changes are not, by themselves, inherently risky. But they create a major challenge for the supervisors, who should upgrade their capacity and tools to connect the dots across sectors.

This resilience reflects to a large extent a wave of regulatory reforms since the crisis, which are now near completion. These were aimed at strengthening regulation and supervision, thus reducing the probability of failures; and lowering the cost of failures and safeguarding the taxpayer. They are aligned with the global regulatory reform agenda, where the U.K. has played a leading role, and were complemented by steps to enhance the governance and conduct of financial firms, as well as the decision to ring-fence retail banking and related services from riskier activities of U.K. banks. Many of these reforms correspond to the recommendations of the 2011 FSAP (Appendix I).

The first major plank of the reforms was to overhaul financial sector oversight and focus it on systemic stability. The new macroprudential framework provides clear roles and responsibilities, adequate powers and accountability, and promotes coordination across agencies. Its track record to-date, albeit short, is encouraging. Microprudential and conduct oversight have also become more rigorous and hands-on. The focus of supervisory effort and resources on the resilience of the most important firms is appropriate from a systemic perspective, but it inevitably implies less individual attention to small and mid-size companies, for which supervisors rely more on data monitoring, thematic reviews, and outlier analysis. This tradeoff warrants constant vigilance, because the business models of smaller firms tend to be correlated and, regardless of their systemic impact, failures of even small firms can be a source of reputational risk for the supervisor. In view of the downward trend of the ratio of risk-weighted to total assets and methodological inconsistencies across banks, internal models should be reviewed closely. A new, sophisticated framework for annual stress tests of major banks is a key link between the microprudential and macroprudential frameworks, but further investment is needed to ensure it can deliver on its ambitious goals.

The BoE’s new liquidity framework is a key shock absorber, and attendant risks seem adequately managed. By ensuring the Bank is “open for business” in the event of distress, the BoE’s flexible framework can help stop the propagation of a shock through liquidity contagion. Access by a broader range of entities, including broker-dealers and CCPs, is a major plus, made possible by the fact that all entities with access to the framework are supervised by the BoE and PRA. Because the relative ease of access to BoE liquidity risks distorting over time the incentives of participating firms, the BoE needs to monitor their behavior for signs of moral hazard or regulatory arbitrage.

The other major plank of the agenda was to ensure that the failure of a financial firm, regardless of its size, would not compromise financial stability or burden the taxpayer. The transposition of the EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive has completed the reform of the U.K.’s Special Resolution Regime for banks, which is now broadly aligned with global standards. The resolution powers, tools, and coordination arrangements for crisis management domestically and cross-border are now much stronger. The key challenge now is to complete the process that will facilitate the resolvability of U.K. financial firms. This is a complex, multi-year task that involves, inter alia, the implementation of ring-fencing and Minimum Requirements for Own Funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL). The authorities should also build on current arrangements to develop operational principles for funding of firms in resolution and establish an effective resolution regime for insurance companies whose failure could be systemic. Finally, given the systemic role played by U.K. banks in smaller jurisdictions that are not part of the Crisis Management Groups (CMGs), the U.K. authorities should develop appropriate cooperation arrangements with such host countries.