In a speech, Richard Sharp, member of the UK Financial Policy Committee, outlined the range of risks within the financial system. One topic he discusses is the buy to let sector, because investors may increase selling pressure in a downturn, if their rental incomes fall below their interest payments or if they observe or anticipate falling property prices. HM Treasury intends to consult this year on whether the FPC should have Direction powers over the buy-to-let mortgage market.

The complexity of global financial systems and markets requires that we aren’t exclusively concerned about the capitalisation of financial institutions. We are also concerned about risk of contagion and amplification and therefore we monitor systemic resilience and vulnerability wherever we see them.

The crash certainly demonstrated how specific vulnerabilities can have massive implications through amplification when the systemic is fragile or stretched. For example, although this summer’s fall in the Shanghai stock market saw peak to trough losses of 2.9 trillion dollars, there was no contagion or amplification in any way comparable to the experience of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. By comparison the US subprime losses which precipitated the financial crisis of 2007-2008 are estimated at around 400 billion dollars but, as we know now, have had a devastating impact. Unfortunately these losses were heavily concentrated on highly leveraged, systemically important financial institutions. As a result of a loss of confidence in the banking system, the subsequent contagion created profoundly greater costs. For example, economists at the IMF estimate that the aggregate cost to the US economy alone was 4.5 trillion dollars in the period of 2007-2009.Comparable UK costs over the same regime were £370 billion.

Consequently, in fulfilling its primary responsibility to contribute to UK financial stability policy, the FPC has to monitor the banking system, the financial system as a whole, and global and domestic potential sources of instability.

A particular challenge is that the UK is the home for an outsized financial sector. Bank of England economists have calculated that in 2013 the UK banking system was 450% of GDP – compared to around 100% in 1975 – larger than in Japan, the US and the ten largest EU economies.

However, a vibrant and successful financial sector is indeed a precious asset for our nation. It is a source of employment for millions of people; it is a critical source of tax revenue; it supports a number of other leading industries based in the UK, such as accounting and law; it provides for inward capital investment; it is one of the few industries in which the UK is a world leader. The FPC is building the capital and resolution framework to contribute to financial stability and to ensure there are no more bailouts.

The importance of the financial services industry to the UK is recognised by the remit the Chancellor has provided for the FPC. He charges the Committee, subject to fulfilling its primary objective on financial stability, to consider the government priority of maintaining the international competitiveness of the UK financial system. However, it is unequivocal government policy that it is unacceptable that UK citizens should underwrite banks’ balance sheets. One of the FPC’s priorities is to provide a capital and resolution framework for banks which ensures that they are capable of absorbing their own losses and are not ‘too big to fail’.

The actual losses borne by the banking system in the UK were unquestionably significant and life threatening; the six largest UK banks faced losses of up to 15% of risk weighted assets (nearly £67 billion in aggregate), with the largest losses concentrated in two institutions, Lloyds and RBS. Of course, the FPC doesn’t exist to stop any financial institution or group of institutions experiencing severe losses. Indeed, and inevitably, there may be severer losses arising from poor credit or investment judgement in the future. Our responsibility is to have the insight to ensure that we are aware of risks to the financial system and that, in particular, the systemically important institutions are well capitalised and that any severe losses don’t threaten the financial system.

However, recognising the risk of excessive regulation, the Chancellor told MPs when discussing the creation of the FPC and its objectives in 2011 – “we don’t want the stability of the graveyard.” What he meant was that although the FPC has been granted significant powers, in using these powers we have to ensure that we don’t unwarrantedly undermine economic growth through excessive regulation.

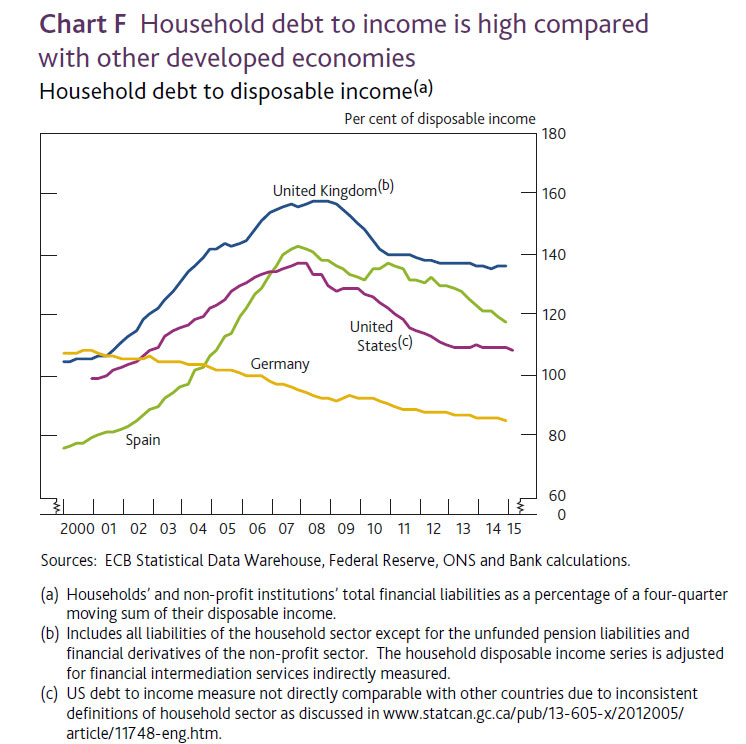

This highlights that there are real trade-offs for us, as we seek to fulfil our mandate. Firstly, we want to have well-capitalised banks but we don’t want to diminish the provision of credit to the real economy. Secondly, whilst we want the provision of credit, we don’t want to risk promoting asset bubbles. Thirdly, given its scale and importance as a source of household indebtedness, we want a disciplined property lending market; on the other hand, we don’t want unreasonably to restrict any individual’s ability to enrich his or her life through a housing purchase. Fourth, we may want to move quickly to ensure resolution, but we have to move in a globally coordinated way, which unavoidably has lengthened the process to agreeing a new resolution regime. Fifth, we want to have a safe and stable financial system, but we do not want to encourage financial services firms to feel incentivised to locate in other jurisdictions with lighter touch regulation, or to inhibit the development of new innovative sources of finance.

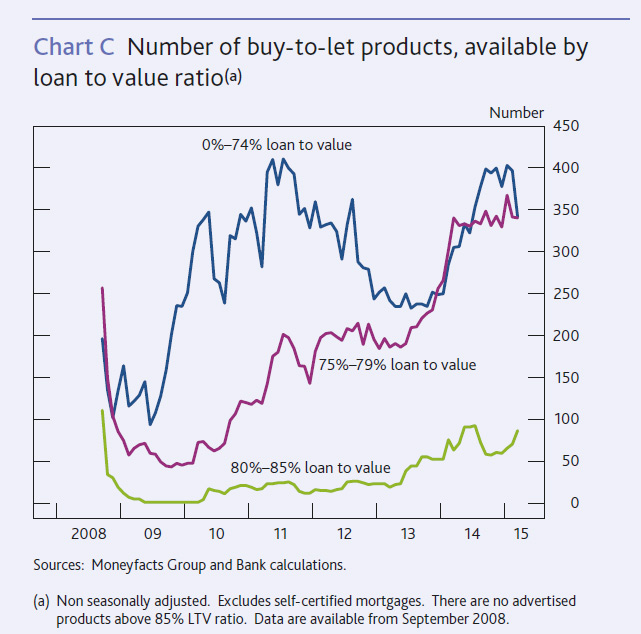

The FPC has been granted considerable powers to give Directions to the PRA and the FCA in relation to the use of certain macroprudential tools specified in secondary legislation. So far, in the area of bank capital requirements, Parliament has given the FPC macroprudential tools over sectoral capital requirements, and leverage ratio requirements. The FPC is also responsible for setting the countercyclical capital buffer for the UK. Further it has Direction powers also in relation to tools with respect to the housing market – currently loan to value and debt to income limits in respect of owner-occupied lending. HM Treasury also plans to consult by the end of this year on whether the FPC should be provided Direction powers over buy-to-let mortgages.

In seeking to preserve financial stability, the FPC can also make Recommendations to anybody, including to the PRA and the FCA on a “comply or explain” basis, and to HM Treasury, including on the boundaries within and around the perimeter of the PRA and FCA regulatory regimes.

In addition to these formal powers, the FPC also works closely with other authorities and committees within the Bank of England on issues of joint interest. For example, the FPC and PRA Board both agreed the design of the annual and concurrent UK bank stress test scenario, the results of which will help inform judgements by both committees.

Before using its powers, the FPC considers a wide range of information, including market and supervisory intelligence.

The Committee has developed a set of Core Indicators that it will consider when using its powers of Direction. These are indicators of key areas where vulnerabilities may build and signal an increase in financial stability risks. For example, the level of credit-to-GDP above its long-run trend (the ‘credit-to-GDP gap’) is one of the key metrics the FPC considers when setting the countercyclical capital buffer, as research suggests that periods of excess credit growth often precede financial crises.

In addition, the FPC is required by law to conduct and publish cost-benefit analysis before using its tools (unless, in the Committee’s opinion, it is not reasonably practicable to do so). In the remit that the Chancellor set out for the FPC in July, he emphasised that the Committee must communicate how decisions to use its powers are compatible with its objectives, including its judgement as to the balance of risks to its objectives, how those risks are judged to have evolved and how they are expected to evolve.

Since its formation in April 2013, the FPC has made 15 Recommendations or Directions on a wide range of topics, including on: bank capital and liquidity requirements; the UK housing market; and the resilience of the UK financial system to cybercrime. We set out our Recommendations in the biannual Financial Stability Report.

So the FPC has been fairly active in addressing risks. But what risks are we concerned about now? In July, the Committee published its Financial Stability Report, which highlighted the six major risks which, in the Committee’s judgement, are facing the UK financial system. These were risks from: (1) the global environment; (2) potential illiquidity in markets; (3) the UK current account deficit; (4) the UK housing market; (5) misconduct in the financial system; and (6) cybercrime. The Committee provided an update on some of these risks in the Record of its meeting in September.

With respect to the global environment, the Committee reported that, for the moment, things are getting somewhat less fragile in the euro area, in particular as a result of the fact that the immediate risks in relation to Greece have been addressed by the new programme agreed between the Greek government and its European partners. However, there are signs that risks to emerging market economies, particularly commodity exporters, have risen and are significant. This is partly as a result of a slowdown in China and the prospects of a potential ‘spill over’ from tighter monetary policy in the US, which could cause a material retrenchment in capital flows, as well as wealth effects. It is worth observing that one effect of US quantitative easing has been a considerable jump in the emerging market credit to GDP growth ratio. Moreover, many of the EMEs have raised significant external capital in US dollars and are therefore also exposed to the risk of currency mismatch. We need to consider whether capital markets can effectively trade such debt given liquidity concerns.

In fact we are concerned that global markets may not be able to absorb large shifts in assets, hence we are examining the capital market provision of liquidity very carefully. This year, there have been a number of short-lived, non-systemic periods of very high market volatility, which exposed the fragility of market liquidity and that disorderly conditions in one market could spill over to others.

In considering the risk of fragile market liquidity, for example assessing dealers’ ability to act as intermediaries in markets, the Bank and the FCA are working at an international level. The Committee is also closely monitoring risks from the UK’s current account deficit. However, despite the deficit being close to record highs (at 5.2% in 2015 Q1), the capital flows funding the deficit are mostly long-term in nature, reducing the risk of investor flight, and do not yet appear to be creating vulnerabilities in specific sectors.

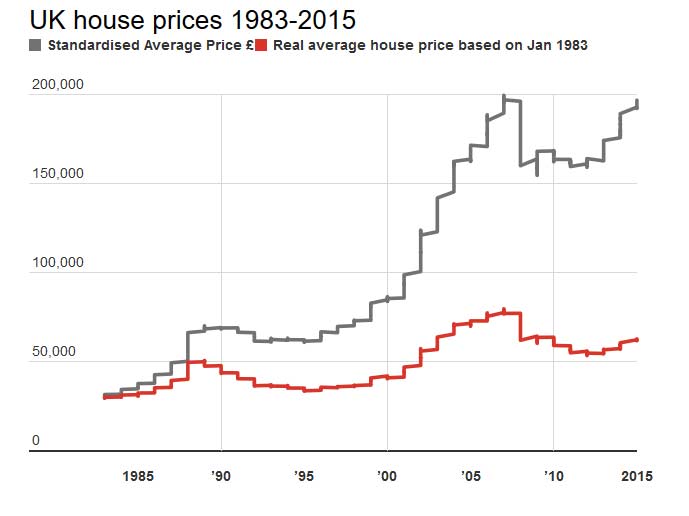

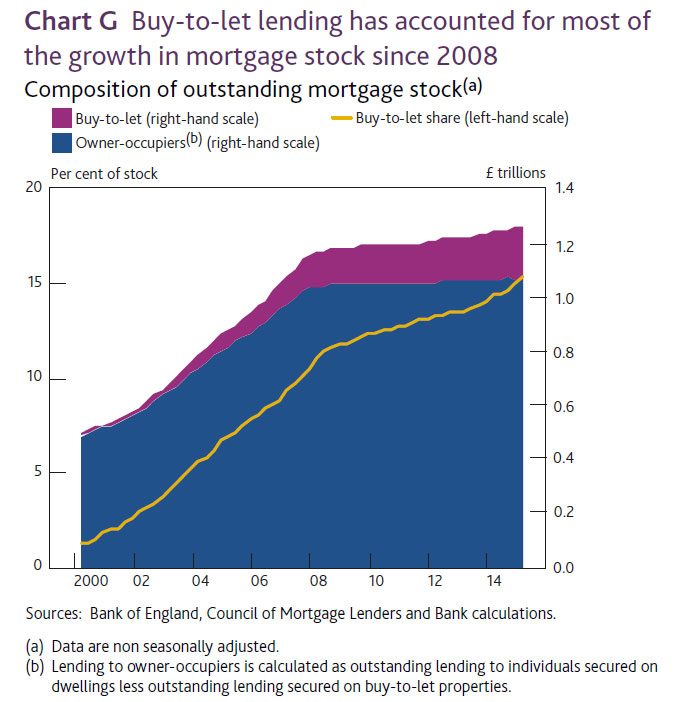

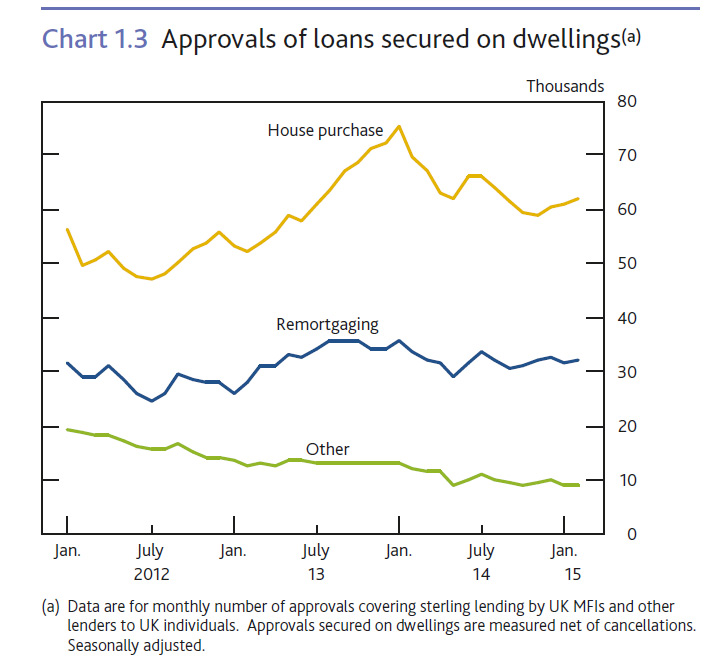

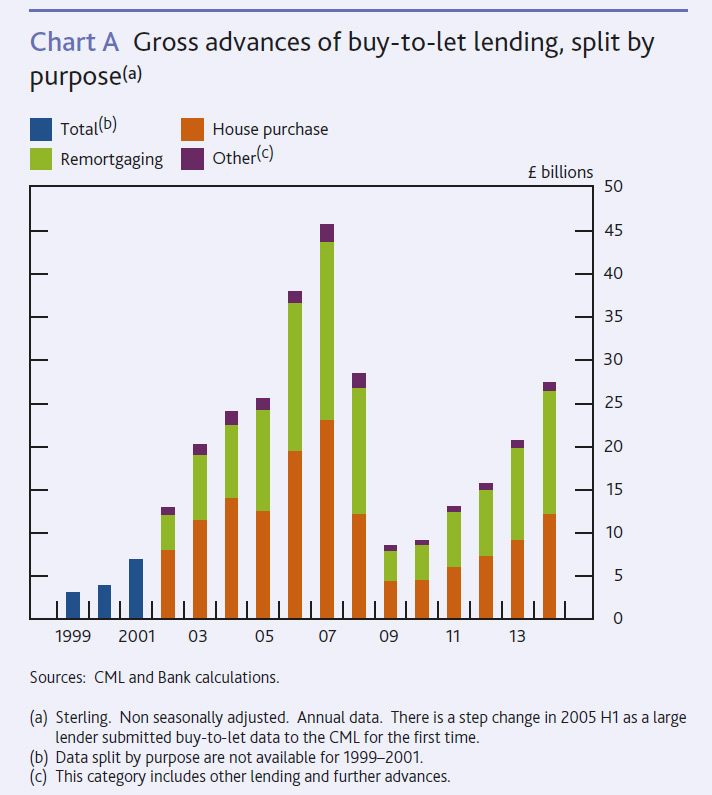

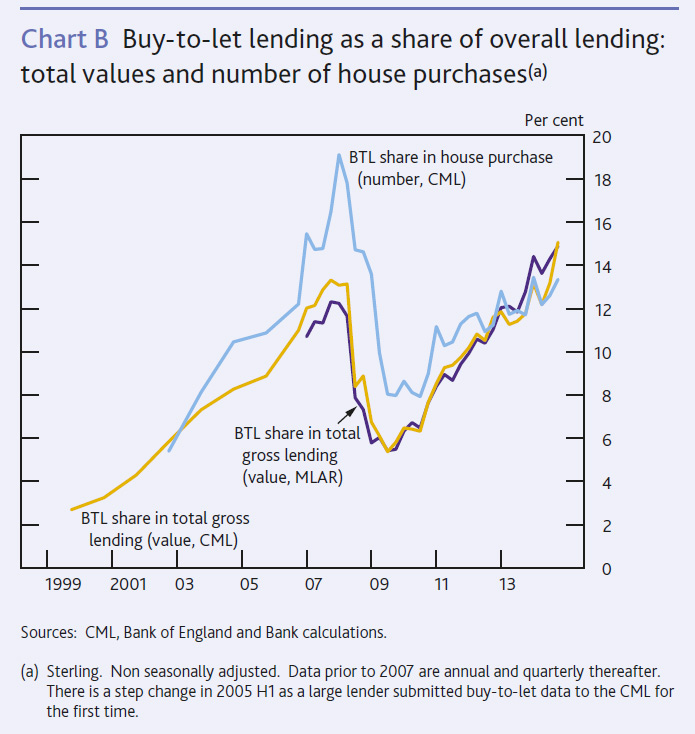

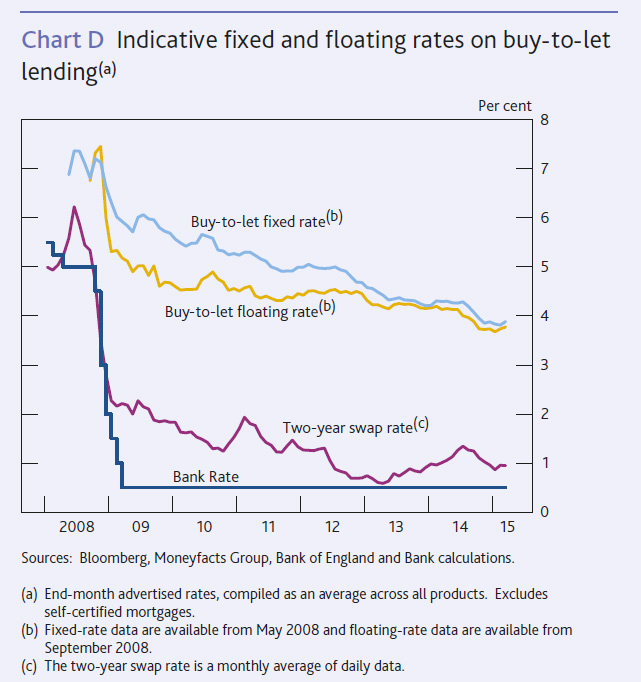

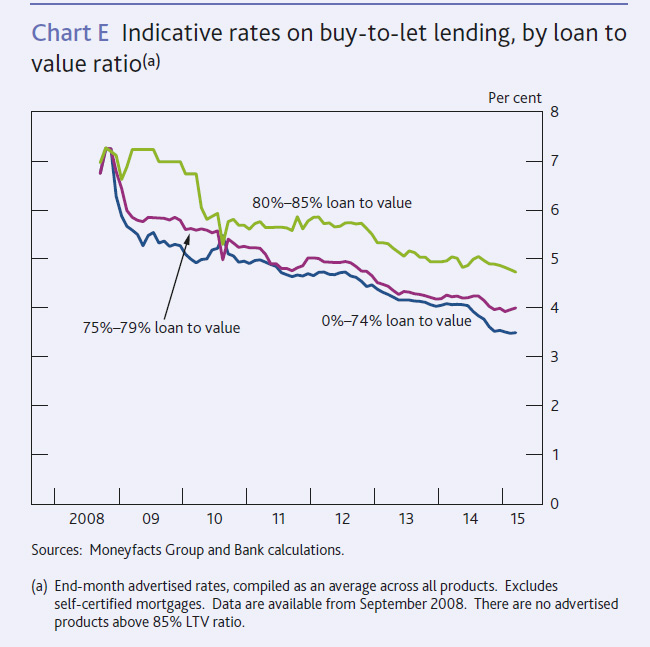

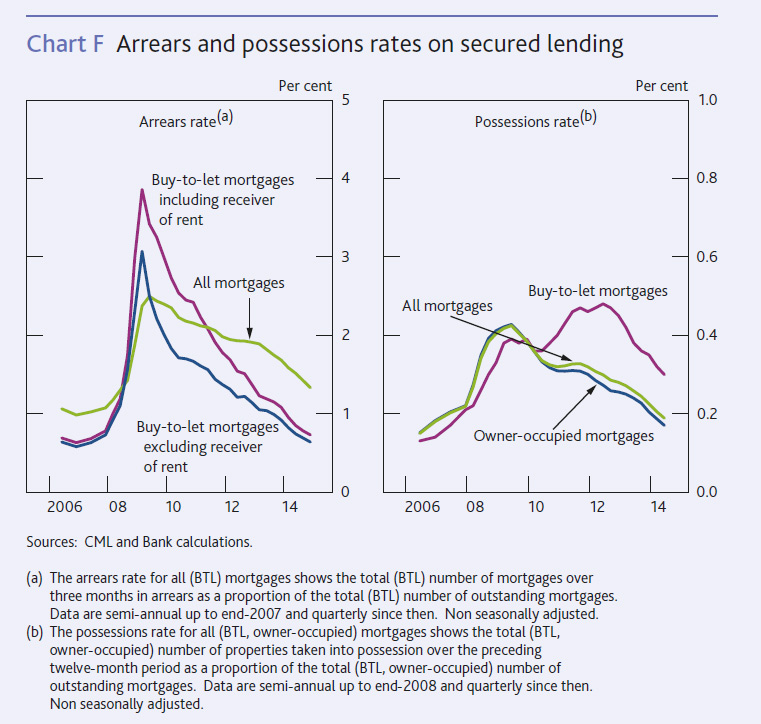

One risk which received a lot of publicity following the publication of the September Record was the UK housing market. It is worth observing how secure the UK housing market has been to investors historically. This can be partly attributed to the fact that mortgages are typically well backed by housing assets, and that in the UK, unlike the US, mortgages are recourse loans, so homeowners can’t just walk away from their debts. However, the rapid growth in the buy-to-let market has caught our attention – the stock of buy-to-let mortgages has increased by over 40% since 2008. Why could this be a cause for concern? Buy-to-let mortgages are typically extended on interest-only terms, meaning their loan-to-value levels fall more slowly over time than owner-occupied mortgages. In addition, buy-to-let mortgages can add to procyclicality in the housing and credit markets, as investors may increase demand for property in an upturn, as they seek capital gains. Buy to let investors may increase selling pressure in a downturn, if their rental incomes fall below their interest payments or if they observe or anticipate falling property prices. As I mentioned earlier, HM Treasury intends to consult this year on whether the FPC should have Direction powers over the buy-to-let mortgage market. I believe it is important that the Committee is provided with powers. Beyond the risks the Committee have identified and, looking longer term, what troubles me?

It’s worth observing that – worryingly – global debt has increased considerably since the crash. It has increased by 57 trillion dollars since 2007 – 2014, outpacing global GDP growth over that period. As I mentioned, I’m most concerned about the fragility arising from this with respect to emerging markets.

Inevitably I have to be concerned that there are even greater risks out there which aren’t anticipated by even the best modellers of risk. As a member of the FPC, I’ve had the benefit of seeing how governmental institutions approach forecasting. It is well known that the Bank, the IMF, and other august institutions failed to anticipate the crash. Here for example is the IMF’s 2007 global financial stability map.

The 2007 version singularly failed to reflect the incipient instability which was present and emerged so devastatingly – notice the radically different 2008 version.

Modelling is hard – In fact, when I first encountered the optimism of some modellers, it brought to my mind a story told by the educator Ken Robinson:

A teacher noticed that a 6 year old girl was working very hard on a drawing and he asked her what she was drawing. She said she was drawing a picture of God. When the teacher said, “But no one knows what God looks like”, she replied – “they will in a minute”.

The Bank’s own approach to forecasting underlines that they recognise limitations which any forecasters must confront. It is clear that a single point one year forecast can be materially different from the outcome in reality. Hence, the Bank produces fan charts which highlight the amplitude of uncertainty. For our Committee, which does have to be concerned about fat tail events, it is worth observing that even the fan chart approach failed to capture the extreme events that occurred in 2007/08.

However, as a practitioner, I think that general expectations of precision from central bank forecasters maybe too great. In the financial sphere we are well aware that not one of all the outstanding brains in the world can, with predictable regularity, determine which way the markets will be even in the next 24 hours let alone the next year. Consequently, whilst, I’m content that the FPC should take account of its indicators and its forecasts, it must always provide for resilience and capital strength that takes account of the reality of unpredictable events.