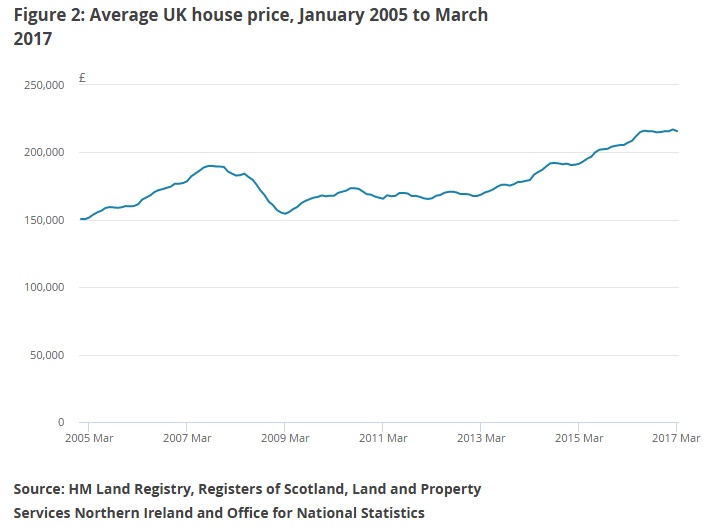

On 22 November, the UK government announced a number of measures in its Autumn Budget, including a stamp duty reduction that will benefit 95% of first-time homebuyers, with a maximum saving of £5,000 per buyer. For purchases completed on or after 22 November 2017, first-time buyers do not have to pay stamp duty on properties worth up to £300,000, while for properties worth up to £500,000 they pay £5,000 less. The stamp duty for purchases above £500,000 is unchanged. Such measures will be credit positive for residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), allowing first-time buyers to amass the down payment they need to take out a loan faster or allow them to borrow a larger amount, strengthening both housing demand and property prices and lowering market-implied loan-to-value ratios on existing loans.

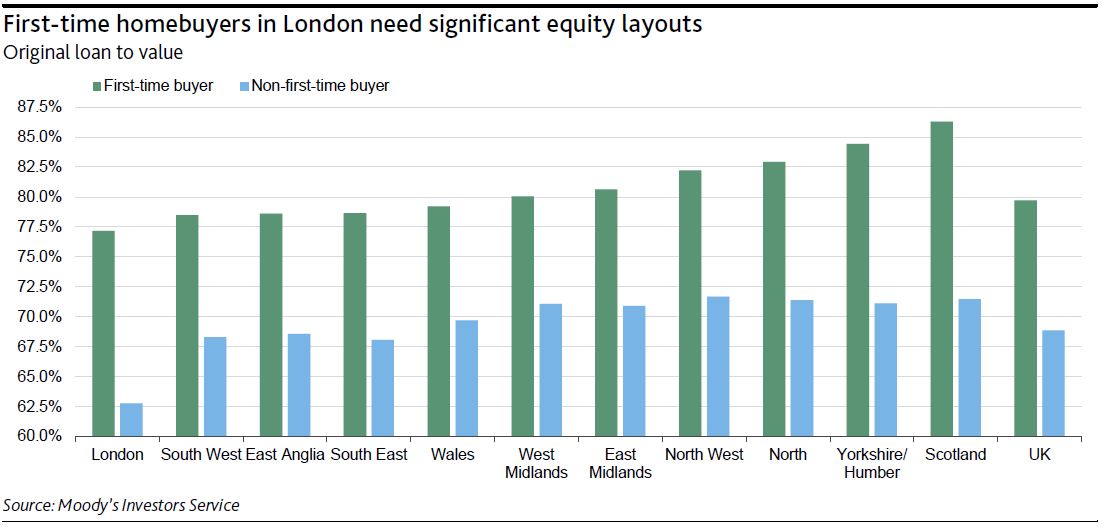

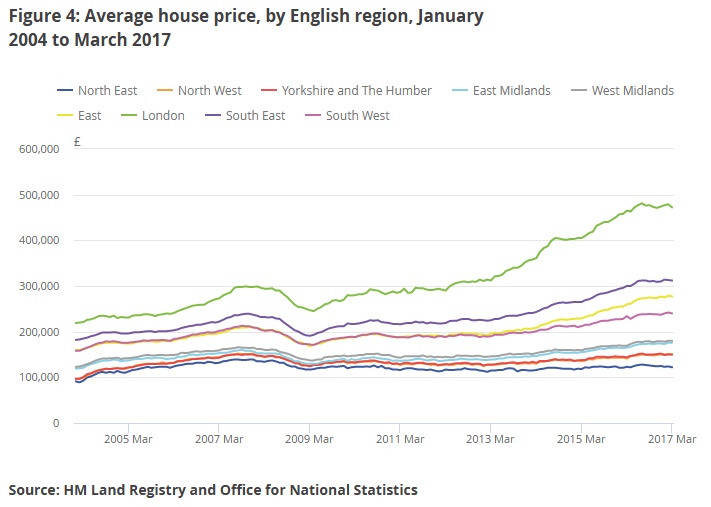

The stamp duty reduction will help alleviate some of the financial burden on first-time buyers amid stagnant wage growth, proportionally more household cost expenditures, and rising rents (rental price inflation in the UK has slowed recently, but was up 0.9% in October 2017 versus a year ago, according to HomeLet). Nevertheless, first-time buyers, especially in London and surrounding counties, still face relatively high equity layouts compared with other regions. Our recent RMBS pool analysis also showed that compared with non-first-time buyers, first-time buyers start with up to 15% less equity in the property (see exhibit).

The budget also confirmed additional funding under the help-to-buy equity loan scheme, another credit positive because it increases the availability of loans for borrowers, while supporting house prices, which overall we expect will remain flat in 2018. Under the scheme, borrowers can purchase a newly built property with just a 5% deposit. Since its launch, borrowers have purchased 120,864 properties, with 81% of the sales attributable to first-time buyers. In 2017, Halifax Ltd. estimated that first-time buyers accounted for almost half of all mortgage-financed house purchases, an important driver of housing demand.