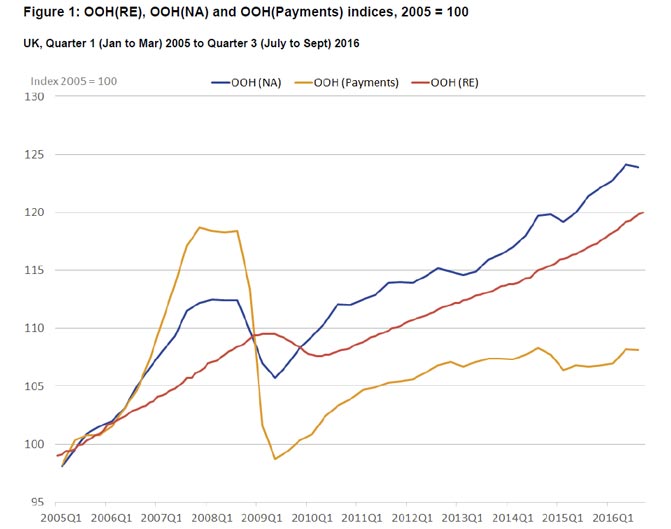

For many of us, our home is the single most important investment we will make in our lifetime and mortgage payments can take up a huge chunk of our income. As politics and economics seem to deliver nothing but uncertainty, how should home owners or first-time buyers react?

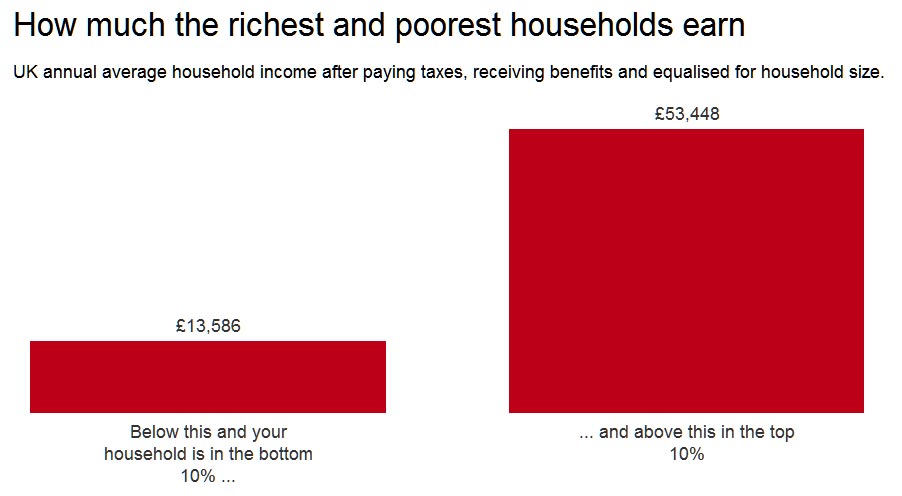

Things still look tight for household budgets. One recent survey showed that the average mortgage payment for a three bedroom house in the UK is about £965 per month, more than half the average take-home wage.

That is with interest rates at historic lows. And they are staying put. The nine members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee have decided to keep the official interest rate in the UK, the Base Rate, at that ultra low level of 0.25%.

The fortified walls of the Bank of England on Threadneedle Street. Robert King/Flickr, CC BY

In various guises, this rate has been around since 1694. It is the rate at which high-street banks borrow from the central bank and its function in the economy is simple but effective. If banks can borrow money cheaply from the Bank of England then they tend to pass it on cheaply to us, the public. When their borrowing gets expensive, so does ours.

The Base Rate is only an overnight interest rate but it starts a domino effect with more long-term interest rates. If it is raised then the whole economy is soon paying more to borrow money.

But if that’s not happening now, what about when the MPC meets again on March 16?

Up, up and away

Let’s start with the bad news for those paying a mortgage or seeking one. Interest rates, and consequently our payments, will definitely increase in the future. The graph below shows the history of the Base Rate since 1970. With a historical average of more than 6% and years when the Base Rate stayed consistently over 12% to combat the spiralling inflation of the time, it becomes evident that a rate of 0.25% is abnormally low.

Bank of England, Author provided

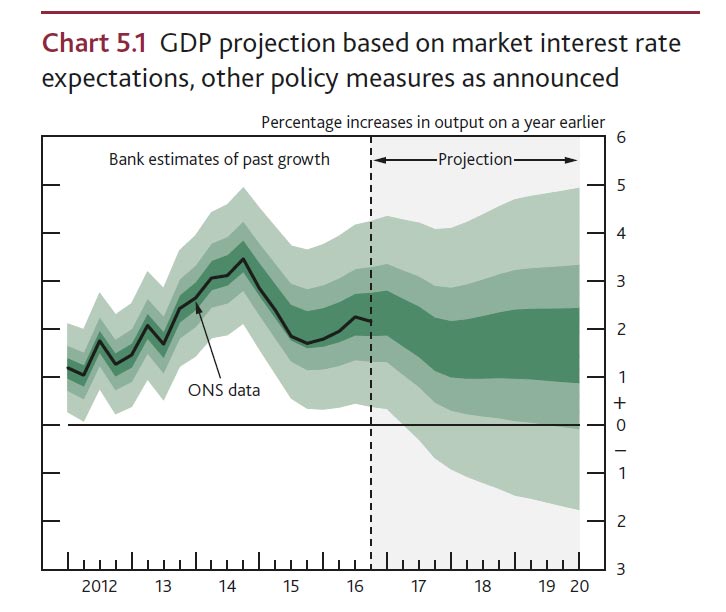

The good news for home owners and house hunters is that interest rates could well stay low for a few more years. And all the signs are that when rates do rise, it will be in small increments of 0.25% or 0.50% every few months. A key aim of the Bank of England is not to surprise markets and to be as predictable as possible, particularly at a time when stability and certainty are rare commodities.

Most people will remember why we ended up with such low rates. In the response to the global financial crisis of 2008, central banks sought to make it cheaper for people to borrow money. A low interest rate makes it easier for consumers to afford not just mortgages but also cars, appliances or nights at the pub. Companies profit from our spending and get access to cheap money that helps them expand or stay afloat.

Debt as a driver. Thomas Hawk/Flickr, CC BY-NC

So, if they are so good for the economy, why do interest rates have to go up again? Mainstream economic theory views very low interest rates as harmful in the longer-term. They are a disincentive to healthy saving rates and when the economy is at full-throttle, they act as a boost to inflation which in turn erodes people’s real incomes. They also distort investment decisions and, particularly dangerously for the UK, add fuel to investment bubbles.

Market forces

Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump in the US, the two great causes of uncertainty these days, will probably save us some money, at least in the short to medium term. Brexit brings with it the prospect that businesses will lose full access to an EU market of 450m affluent Europeans. In a climate like this, it would be a foolhardy Bank of England which chose to make money more expensive in the UK.

Trump, meanwhile, is known to favour a cheap dollar and low interest rates in the US in an effort to make exports more competitive. The Bank of England, as ever, will keep a close eye on its US counterpart, and will likely avoid increasing UK interest rates for fear of pushing the pound higher and blocking out much needed investment from the US.

So how can you use this information?

First of all, I’d avoid taking a mortgage or any loan that I could only barely afford as rates will eventually rise. For those that already have a mortgage, most commentary on the real-estate market will advocate for a fixed-term mortgage but that is not necessarily a good idea. The most popular fixed-term products offered by high street banks are usually for a period of two years.

The trouble here is that you will normally pay a fee and a higher interest rate as the cost for fixing, during which time rates are unlikely to rise anyway. And so only fixed mortgages of five years or more start making sense – and you would still pay fees and a relatively higher interest rate for a couple of years before you started to benefit.

A good idea would be to make small but regular overpayments into your mortgage, and request that these payments are used to reduce your monthly instalments (rather than to bring closer the year that the loan will be repaid in full). So when the interest rate does increase in the future, the outstanding amount it will apply to will be reduced. Flexible mortgages typically accept unlimited overpayments and even the fixed deals usually allow overpayments of up to 10% each year.

Banks are not particularly happy with the overpayment approach. It reduces their profits and de-stabilises their portfolio a little. But reluctant banks are usually a sign that this might just be a good deal for you.