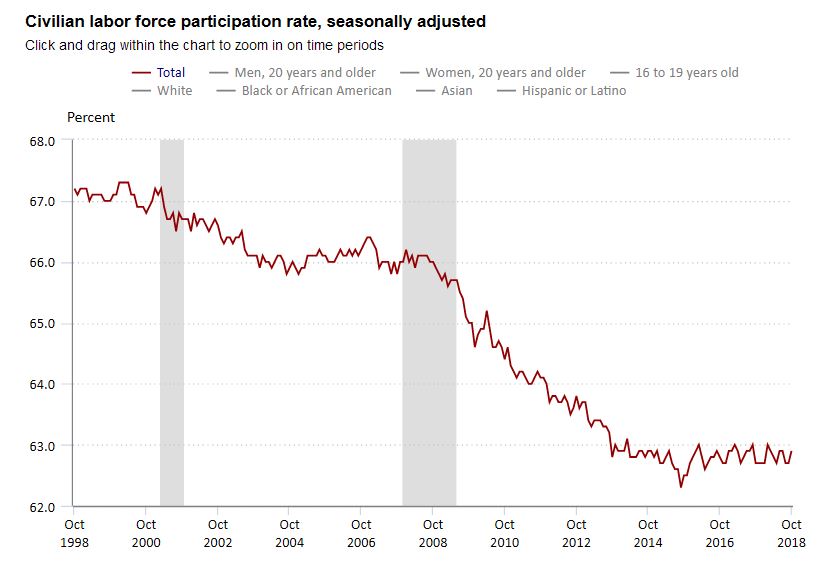

The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons (sometimes referred to as involuntary part-time workers) was essentially unchanged at 4.6 million in October. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs.

In October, 1.5 million persons were marginally attached to the labor force, little changed from a year earlier. (Data are not seasonally adjusted.) These individuals were not in the labor force, wanted and were available for work, and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months. They were not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey.

Among the marginally attached, there were 506,000 discouraged workers in October, about unchanged from a year earlier. (Data are not seasonally adjusted.) Discouraged workers are persons not currently looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them. The remaining 984,000 persons marginally attached to the labor force in October had not searched for work for reasons such as school attendance or family responsibilities.

Total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 250,000 in October, following an average monthly gain of 211,000 over the prior 12 months. In October, job growth occurred in health care, in manufacturing, in construction, and in transportation and warehousing.

Health care added 36,000 jobs in October. Within the industry, employment growth occurred in hospitals (+13,000) and in nursing and residential care facilities (+8,000). Employment in ambulatory health care services continued to trend up (+14,000). Over the past 12 months, health care employment grew by 323,000.

In October, employment in manufacturing increased by 32,000. Most of the increase occurred in durable goods manufacturing, with a gain in transportation equipment (+10,000). Manufacturing has added 296,000 jobs over the year, largely in durable goods industries.

Construction employment rose by 30,000 in October, with nearly half of the gain occurring among residential specialty trade contractors (+14,000). Over the year, construction has added 330,000 jobs.

Transportation and warehousing added 25,000 jobs in October. Within the industry, employment growth occurred in couriers and messengers (+8,000) and in warehousing and storage (+8,000). Over the year, employment in transportation and warehousing has increased by 184,000.

Employment in leisure and hospitality edged up in October (+42,000). Employment was unchanged in September, likely reflecting the impact of Hurricane Florence. The average gain for the 2 months combined (+21,000) was the same as the average monthly gain in the industry for the 12-month period prior to September.

In October, employment in professional and business services continued to trend up (+35,000). Over the year, the industry has added 516,000 jobs.

Employment in mining also continued to trend up over the month (+5,000). The industry has added 65,000 jobs over the year, with most of the gain in support activities for mining.

Employment in other major industries–including wholesale trade, retail trade, information, financial activities, and government–showed little change over the month.

The average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls increased by 0.1 hour to 34.5 hours in October. In manufacturing, the workweek edged down by 0.1 hour to 40.8 hours, and overtime was unchanged at 3.5 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls, at 33.7 hours, was unchanged over the month.

In October, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 5 cents to $27.30. Over the year, average hourly earnings have increased by 83 cents, or 3.1 percent. Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees increased by 7 cents to $22.89 in October.

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for September was revised down from +134,000 to +118,000, and the change for August was revised up from +270,000 to +286,000. The downward revision in September offset the upward revision in August. (Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.) After revisions, job gains have averaged 218,000 over the past 3 months.