Seasonally adjusted household survey data have been revised using updated seasonal adjustment factors, a procedure done at the end of each calendar year. Seasonally adjusted estimates back to January 2013 were subject to revision.

Household Survey Data

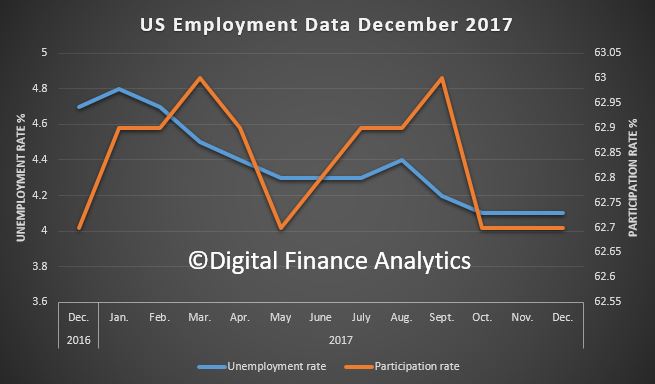

In December, the unemployment rate was 4.1 percent for the third consecutive month. The number of unemployed persons, at 6.6 million, was essentially unchanged over the month. Over the year, the unemployment rate and the number of unemployed persons were down by 0.6 percentage point and 926,000, respectively.

Among the major worker groups, the unemployment rate for teenagers declined to 13.6 percent in December, offsetting an increase in November. In December, the unemployment rates for adult men (3.8 percent), adult women (3.7 percent), Whites (3.7 percent), Blacks (6.8 percent), Asians (2.5 percent), and Hispanics (4.9 percent) showed little or no change.

Among the unemployed, the number of new entrants decreased by 116,000 in December. New entrants are unemployed persons who never previously worked.

The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) was little changed at 1.5 million in December and accounted for 22.9 percent of the unemployed. Over the year, the number of long-term unemployed declined by 354,000.

The labor force participation rate, at 62.7 percent, was unchanged over the month and over the year. The employment-population ratio was unchanged at 60.1 percent in December but was up by 0.3 percentage point over the year.

The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons (sometimes referred to as involuntary part-time workers) was essentially unchanged at 4.9 million in December but was down by 639,000 over the year. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been cut back or because they were unable to find a full-time job.

In December, 1.6 million persons were marginally attached to the labor force, about unchanged from a year earlier. (The data are not seasonally adjusted.) These individuals were not in the labor force, wanted and were available for work, and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months. They were not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey.

Among the marginally attached, there were 474,000 discouraged workers in December, little changed from a year earlier. (The data are not seasonally adjusted.) Discouraged workers are persons not currently looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them. The remaining 1.1 million persons marginally attached to the labor force in December had not searched for work for reasons such as school attendance or family responsibilities.

Establishment Survey Data

Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 148,000 in December. Job gains occurred in health care, construction, and manufacturing. In 2017, payroll employment growth totaled 2.1 million, compared with a gain of 2.2 million in 2016.

Employment in health care increased by 31,000 in December. Employment continued to trend up in ambulatory health care services (+15,000) and hospitals (+12,000). Health care added 300,000 jobs in 2017, compared with a gain of 379,000 jobs in 2016.

Construction added 30,000 jobs in December, with most of the increase among specialty trade contractors (+24,000). In 2017, construction employment increased by 210,000, compared with a gain of 155,000 in 2016.

In December, manufacturing employment rose by 25,000, largely reflecting a gain in durable goods industries (+21,000). Manufacturing added 196,000 jobs in 2017, following little net change in 2016 (-16,000).

Employment in food services and drinking places changed little in December (+25,000). Over the year, the industry added 249,000 jobs, about in line with an increase of 276,000 in 2016.

In December, employment changed little in professional and business services (+19,000). In 2017, the industry added an average of 44,000 jobs per month, in line with its average monthly gain in 2016.

Employment in retail trade was about unchanged in December (-20,000). Within the industry, employment in general merchandise stores declined by 27,000 over the month. Retail trade employment edged down in 2017 (-67,000), after increasing by 203,000 in 2016.

Employment in other major industries, including mining, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing, information, financial activities, and government, changed little over the month.

The average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls was unchanged at 34.5 hours in December. In manufacturing, the workweek edged down by 0.1 hour to 40.8 hours, while overtime remained at 3.5 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls was unchanged at 33.8 hours.

In December, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 9 cents to $26.63. Over the year, average hourly earnings have risen by 65 cents, or 2.5 percent. Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees increased by 7 cents to $22.30 in December.

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for October was revised down from +244,000 to +211,000, and the change for November was revised up from +228,000 to +252,000. With these revisions, employment gains in October and November combined were 9,000 less than previously reported. (Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.) After revisions, job gains have averaged 204,000 over the last 3 months.

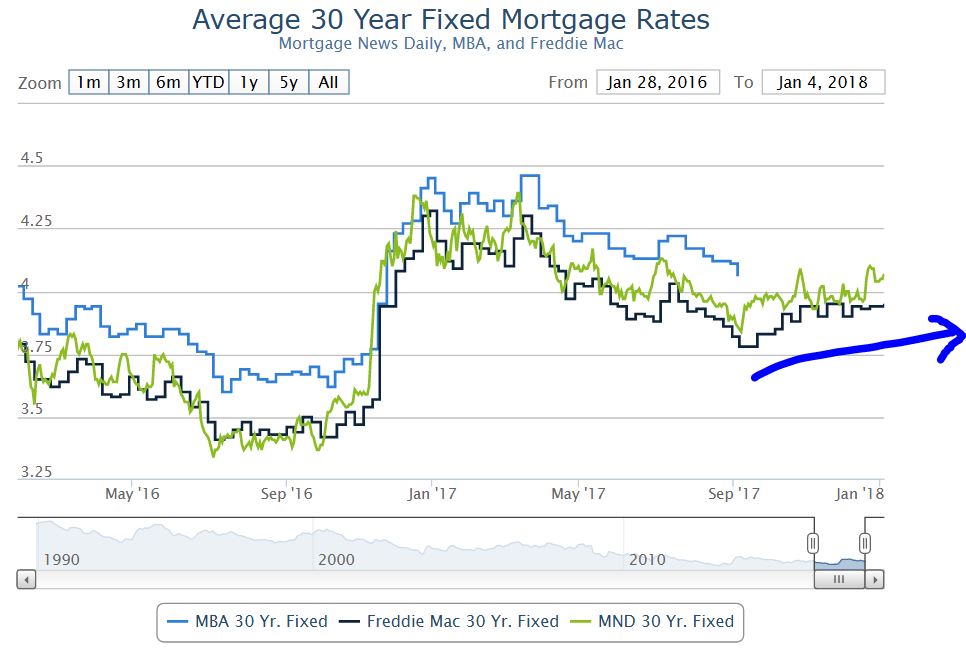

So this piece from Moody’s is interesting. Is the markets view that rates won’t go higher credible?

So this piece from Moody’s is interesting. Is the markets view that rates won’t go higher credible?