In the span of just six quarters between 2007 and 2009, nonfarm business output declined by $753 billion and 8.1 million jobs were lost. This period, known as the Great Recession, was the worst American recession since the Great Depression. The U.S. economy has been recovering from this historic decline for 7 years and is now in the midst of the one of the longest business cycles of the post–World War II (WWII) era. At this point, there are enough data for us to see how this business cycle is shaping up compared with past cycles, and we may ask, “How well, exactly, are we doing?” and “How much have we recovered, up to this point in this cycle?” The productivity measures published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) are very useful in addressing these questions, because they make connections between important economic indicators, including output, employment, labor hours, worker compensation, and inflation. With regard to labor productivity itself, it has become clear that the United States is in one of its slowest-growth periods since the end of WWII.

This issue of Beyond the Numbers analyzes the historically slow U.S. labor productivity growth observed during the current business cycle and addresses the implications for the U.S. economy.

What is labor productivity?

Labor productivity is a measure of economic performance that compares the amount of goods and services produced (output) with the number of labor hours used in producing those goods and services. It is defined mathematically as real output per labor hour, and growth occurs when output increases faster than labor hours. Labor productivity growth can be estimated from the difference in growth rates between output and hours worked. For example, if output is rising by 3 percent and hours are rising by 2 percent, then labor productivity is growing by 1 percent.

Technological advances, greater investment in machinery and equipment by businesses, increases in worker skill and experience, and other improvements to production can all lead to labor productivity growth. The labor productivity measure encompasses the overall contribution of all of these advances over a given period. BLS publishes quarterly and annual series of labor productivity for major sectors of the U.S. economy beginning with data for 1947.

So, why is it important to measure productivity? This is because productivity growth has the potential to lead to improved living standards for those participating in an economy, in the form of higher income, greater leisure time, or a mixture of both. With gains in labor productivity, an economy is able to produce increasingly more goods and services for a given number of hours of work. These gains in efficiency make it possible for an economy to achieve growth in labor income, profits and capital gains of businesses, and public sector revenue. Moreover, as labor productivity grows, it may be possible for all of these factors to increase simultaneously, without gains in one coming at the cost of one of the others. Also, looked at another way, gains in labor productivity may allow for increased leisure time because, with higher productivity, an economy can produce the same amount of goods and services in fewer work hours and, in some cases, even produce more goods and services in fewer work hours.

However, if productivity fails to grow significantly—as has been the case in recent years—those participating in an economy are left with a level of goods and services that fails to grow substantially, making it more difficult to attain widespread gains in income. It is thus important to track labor productivity, because it is the benchmark for potential gains in income of U.S. workers and shareholders.

How are we doing at this point in the current business cycle?

Now let us look at the productivity growth data of the current business cycle. Why are we looking at business cycles, you may be wondering? This is because, being based on the highly cyclical output and hours data, productivity data tend to possess a cyclical element. Thus, it makes sense to compare periods that take this feature of the data into account and that each contain one recession and one expansion. This approach allows for consistent and standardized comparisons of productivity trends through time.

During the current business cycle, which started in the fourth quarter of 2007, labor productivity has grown at an annualized rate of 1.1 percent. This growth rate is notably low compared with the rates of the 10 completed business cycles since 1947—only a brief six-quarter cycle during the early 1980s posted a cyclical growth rate that low (also increasing 1.1 percent). Of course, the current business cycle is not yet over, and its rate of growth is likely to change as more quarters of data are added. However, an analysis up to this point is warranted, given that this business cycle is now the fourth-longest cycle since 1947. In addition, comparing the current cycle with the completed cycles enables us to get a sense of the extent of the growth we will need to achieve during the remainder of this cycle in order to catch up to historical trends. Having this context will allow us to better gauge how well our economy is doing in the coming months and years.

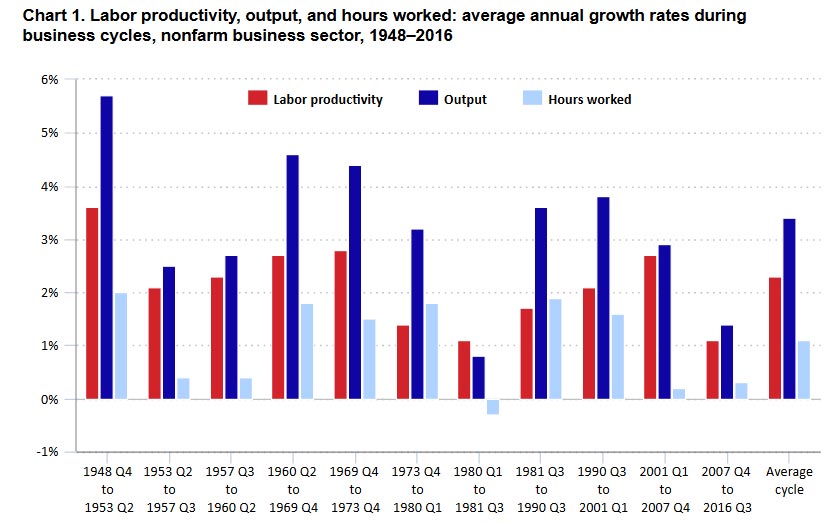

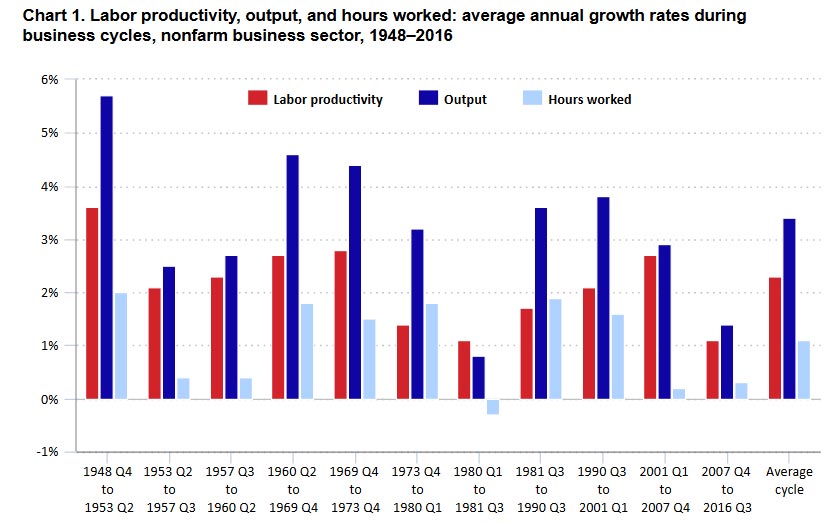

The growth rates of labor productivity, output, and hours for all business cycles since 1947, including the average-cycle rates,5 are shown in chart 1. We see that the labor productivity growth rate (shown in red) for the current business cycle is the lowest productivity growth rate in the chart, sharing that distinction with a brief six-quarter cycle in the early 1980s which also had 1.1-percent growth. Also noteworthy is the output growth rate of the current cycle: at 1.4 percent, it is the second-lowest output growth rate of the historical period and well below the average-cycle output growth rate of 3.4 percent. Hours also had low growth, posting a 0.3-percent rate over the period, below its average-cycle rate of 1.1 percent.

While hours growth during the current business cycle was 0.8 percentage point below its business cycle average of 1.1 percent, output growth was 2.0 percentage points below its business cycle average of 3.4 percent. So, although both hours and output grew at below-average rates during this cycle, the fact that output grew notably slower than its historical average is what yields the historically low labor productivity growth rate of 1.1 percent.

Now let us look more deeply into the output and hours data and see how each has been moving during the current business cycle relative to its historical trend and how each of these series is reflected in the low labor productivity growth of this cycle.

Output growth in the current business cycle

The below-average rate of output growth in the current business cycle had contributions from both phases of the cycle: the Great Recession and the subsequent recovery. The Great Recession had the largest total decline in output of any recession in the post–WWII era (a 6.7-percent overall decline). Following that historic decline, the recovery has had the lowest output growth rate (2.6 percent per year) of any recovery since 1947. These two factors have combined to yield an output growth rate for this cycle (1.4 percent per year) that is very low by historical standards. Only the brief 1980 cycle had a lower rate, and all nine other cycles had growth rates of at least 2.5 percent, well above the output growth rate of the current cycle. (Compare the dark blue bars in chart 1.)

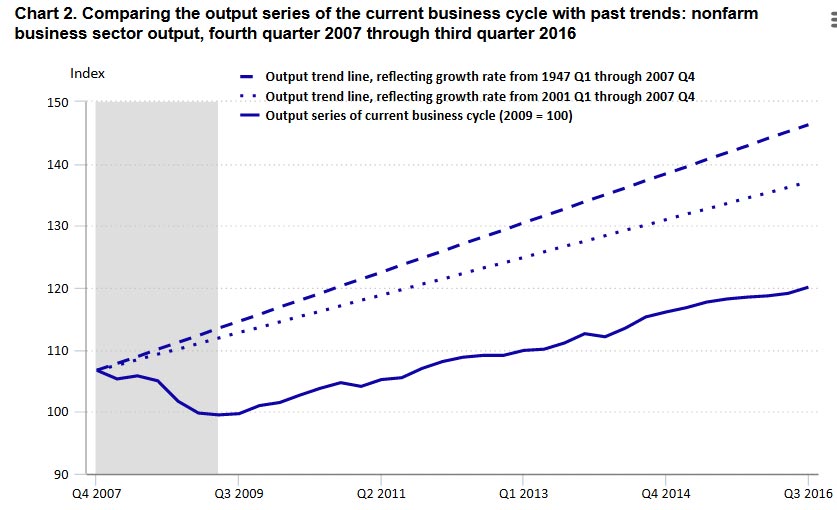

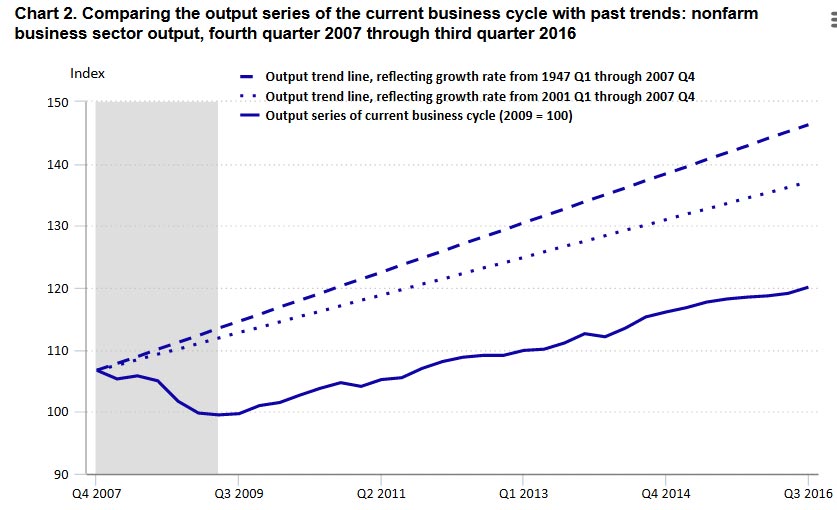

A key aspect of the recovery thus far is that, not only has output growth been well below historical trends, but it is even further behind the growth rates necessary to overcome the effect of the massive decline in output during the Great Recession. To counteract such a large decline and lift the current cycle’s growth rate back up to historical averages, output would have had to grow much faster than average during the recovery. But output has done the opposite thus far, growing more slowly than average during the recovery.

You may be wondering how large of an output growth rate during the recovery would have been required to lift this business cycle’s output growth back up to the long-term trend. The answer is that it would have taken a 5.5-percent growth rate up to this point in the current recovery to lift this cycle’s output growth rate up to the 3.7-percent long-term rate registered from 1947 to 2007. That 5.5-percent rate is 2.9 percentage points higher than the actual 2.6-percent growth rate of the recovery. We can also calculate the rate necessary to lift this cycle’s growth rate to that of the more recent trends. For example, to attain the 2.9-percent growth rate of the last business cycle—from the first quarter of 2001 to the fourth quarter of 2007—the current recovery would have needed a 4.5-percent output growth rate—1.9 percentage points higher than the growth rate posted thus far in this business cycle.

The gap between the current output series and historical trend rates can be seen in chart 2. The output series of the current business cycle is shown by the solid dark-blue line, and the dashed and dotted dark-blue lines show the trends in output for the entire historical period and the last business cycle. Comparing the current output series with the long-term output growth trend from 1947 to 2007 (the dashed dark-blue line), we can see that the current series lies well below this trend line and that the gap between the series has widened since the end of the recession. Put in dollar terms, the gap between the actual output and this hypothetical output if it had continued to follow the 1947-to-2007 output trend during this cycle is now more than $2.7 trillion, or over $22,900 in lost annual output per job in the nonfarm business sector. Comparing the current series with the trend rate from the previous business cycle (the dotted dark-blue line) also reveals that the output gap has widened since the end of the recession, although by less than the full historical trend indicates.

These historical comparisons make it clear that the shock to output growth which took place during the Great Recession has not been resolved. The fact that output growth has not risen above 3.2 percent in any single year since the recession underlines the fact that the higher-than-average growth rates which would be necessary for the U.S. economy to climb back to pre-recessionary trends have not been present during this recovery. At this point in the recovery, it would require a dramatic increase in output growth rates to resolve this situation.

Hours growth in the current business cycle

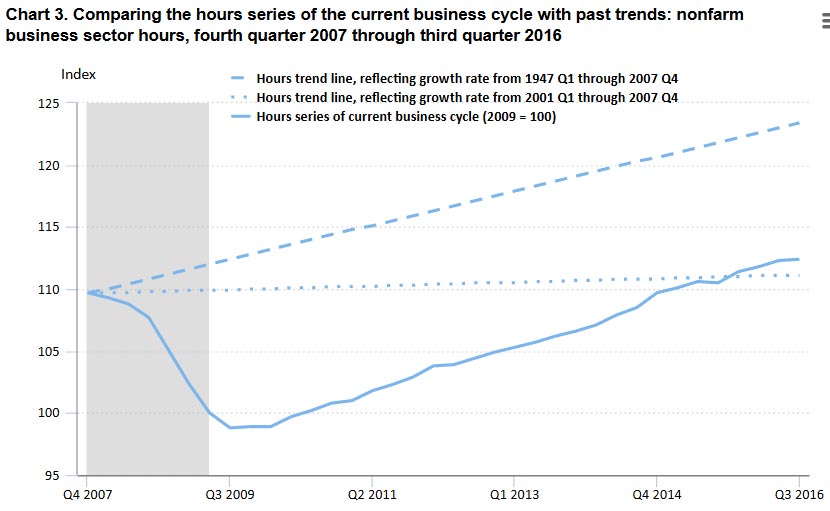

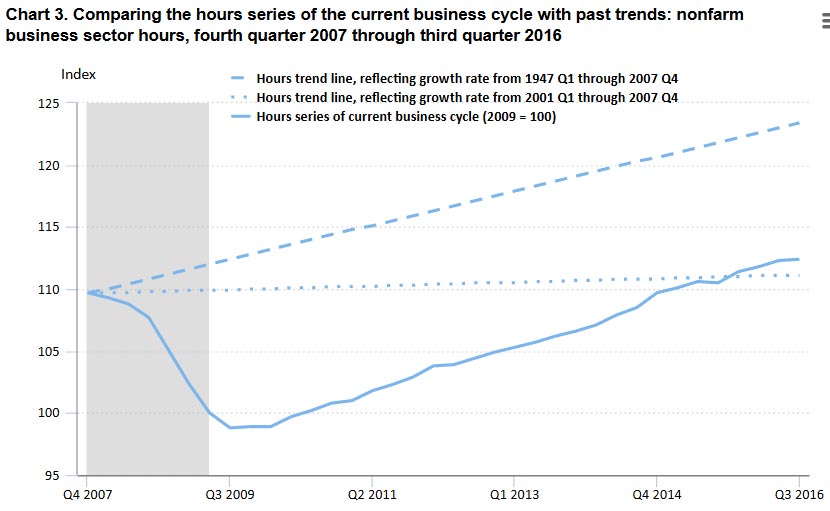

Just as with output growth, we can perform a long-term comparative analysis on the hours growth in the current business cycle. During the Great Recession, hours sustained an overall decline of 9.9 percent (or 19.4 billion labor hours) from the business cycle peak in the fourth quarter of 2007 until its subsequent low point in the third quarter of 2009. Following that decline, hours have grown during this recovery at an average annual rate of 1.9 percent. Chart 3 shows how hours have fared throughout this business cycle relative to historical trends. The first thing you might notice is that there is no gap in hours growth between this business cycle and the cycle that ran from the first quarter of 2001 to the fourth quarter of 2007. In fact—as can be seen by looking at the right side of the chart—hours growth in the current cycle (the solid light-blue line) has already surpassed that of the 2001–07 period (the dotted light-blue line). As of the third quarter of 2016, hours have grown during this business cycle at an annual rate of 0.3 percent, compared with 0.2-percent growth over the last cycle. The 1.9-percent hours growth rate during the current recovery was key to closing the gap in growth between this cycle and the last one.

You might also notice that the slope of the hours line of the current recovery is slightly steeper than the slope of the line representing the 1947-to-2007 trend (the dashed light-blue line). This relationship indicates that the current recovery’s hours growth has outpaced its long-term historical trend and has thus helped this business cycle’s growth rate begin to catch up to that long-term trend. However, a gap remains between the overall growth of the current cycle and hours growth over the long-term historical period. In order for the current-cycle hours growth to match the trend from 1947 to 2007, hours would have needed to grow 3.2 percent during the recovery thus far; this rate is 1.3 percentage points above the current-recovery rate of 1.9 percent. So, we can say that, although the hours growth rate up to this point in this business cycle is similar to the rate from the last cycle, hours have still grown at rates below the long-term historical trend.

Overall, hours have recovered much better than output, having fully caught up to the growth rate of the last business cycle and even having made some progress toward catching up to the long-term trend. Output, in contrast, is still far behind both its recent and its long-term trend, and has made no progress in catching up to those trends during its recovery, as is shown by the substantial gap in growth remaining as of the third quarter of 2016—a gap that is even larger than that existing at the end of the Great Recession. (See chart 2.)

Labor productivity growth in the current business cycle

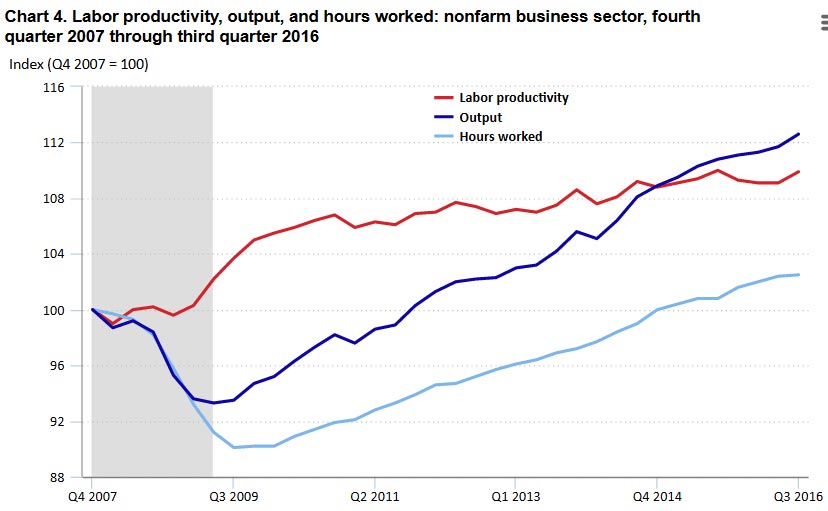

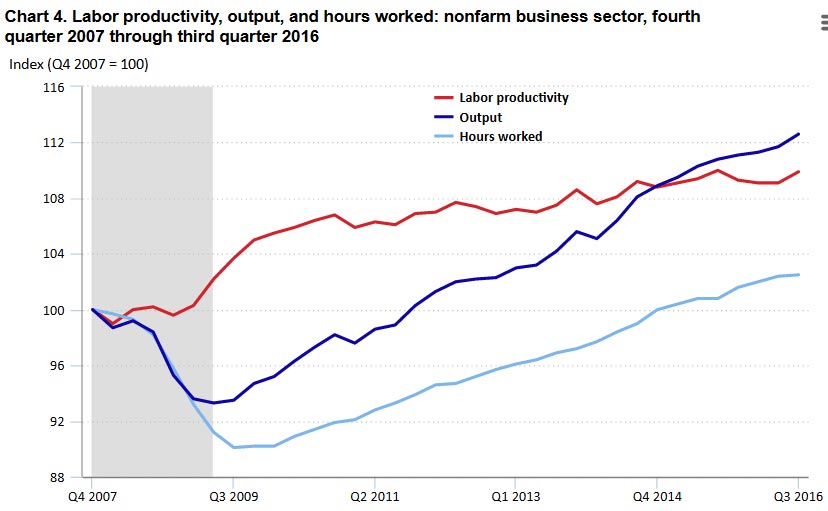

Now let us look at how the growth in output and the growth in hours combine to yield the historically low labor productivity growth of the current business cycle. Chart 4 reveals that, through most of the Great Recession, labor productivity was relatively flat, as output and hours were declining simultaneously. However, as the recession was ending, productivity shot up when output stabilized while hours continued to fall. In fact, nearly half of the overall productivity growth during the current business cycle occurred in just the period from the fourth quarter of 2008 to the fourth quarter of 2009. The high productivity growth of that yearlong period comes from the fact that the largest overall output decline (–6.7 percent) since the Great Depression was surpassed by an even larger decline in hours worked (–9.9 percent). This example shows that, although productivity grows when output rises by a larger amount than hours, productivity also grows when output declines by a smaller amount than hours.

Following the spike in productivity which occurred in 2009, both output and hours grew at rates that were relatively similar to one another during the remainder of the recovery, resulting in the very low productivity growth seen during this period. Over the last 5 years shown in chart 4, labor productivity grew at an average rate of just 0.7 percent, with output growing 2.6 percent and hours growing 1.9 percent. The 0.7-percent labor productivity growth rate during these years is less than one-third the long-term rate of productivity growth of 2.3 percent posted from 1947 to 2007.

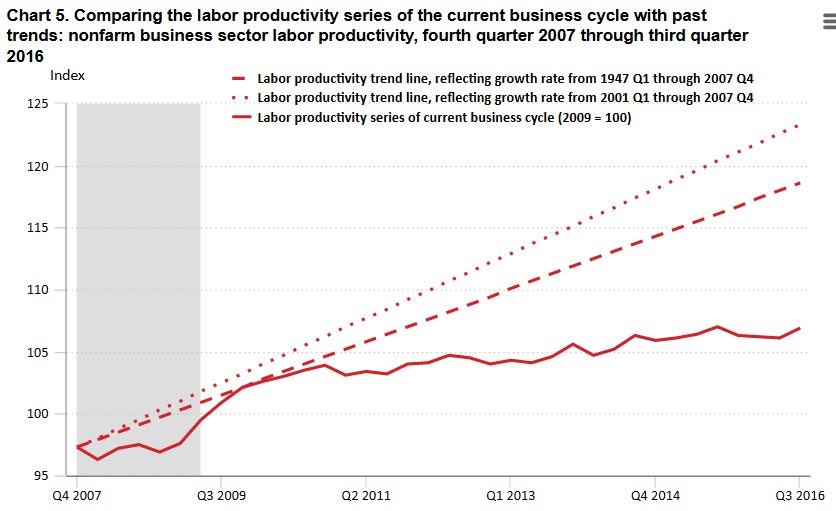

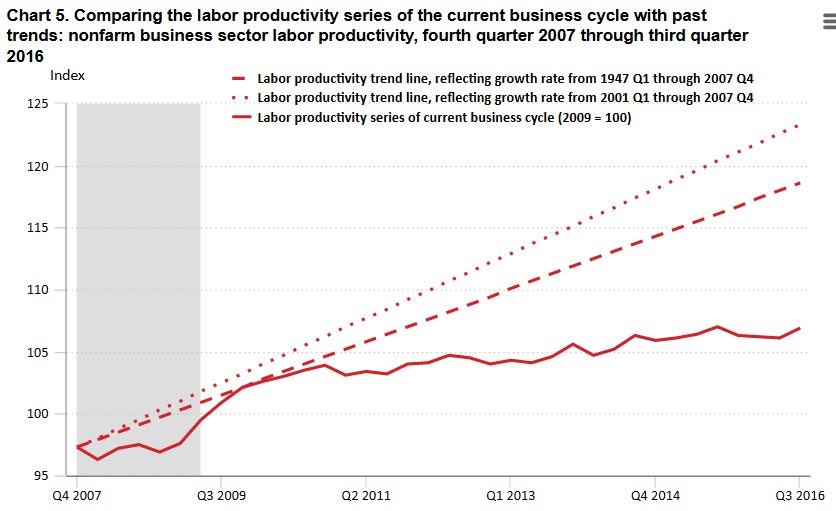

Just as we saw with output and hours, we can see how labor productivity has performed in the current business cycle relative to historical trends. Chart 5 shows labor productivity during this business cycle (the solid red line) compared with trends for the same historical periods that we used to analyze output and hours. Through most of the Great Recession, labor productivity lagged behind historical growth rates, but then it achieved above-average gains coming out of the recession and into the early quarters of the recovery. The U.S. economy actually caught up to the long-term historical trend (the dashed red line) in the fourth quarter of 2009, although it was still slightly behind the trend from the last cycle (the dotted red line) at that point. However, after 2010, productivity growth stagnated and a substantial deficit relative to historical trends developed over the next 5 years. By the third quarter of 2016, labor productivity in the current business cycle had grown at an average rate of just 1.1 percent, well below the long-term average rate of 2.3 percent from 1947 to 2007 and even further behind the 2.7-percent average rate over the cycle from 2001 to 2007.

Ultimately, the fact that labor hours have outpaced their historical trend during this recovery while output has fallen further behind its historical trend is what yields the low productivity of the current cycle. This combination is illustrated on the right side of chart 5, where the stagnation of labor productivity growth is plainly visible.

Dramatic gains in labor productivity growth would be required in coming years to counteract the stagnation of recent years and lift the series back up to the long-term historical trend. For example, it would require a constant productivity growth rate of 7.7 percent during each of the next 2 years in order to lift the labor productivity growth of the current cycle back up to the historical trend rate seen from 1947 to 2007. This rate of growth would be 7 times that of this business cycle thus far, and 11 times the rate experienced during the last 5 years.

Wage gap growth in the current business cycle

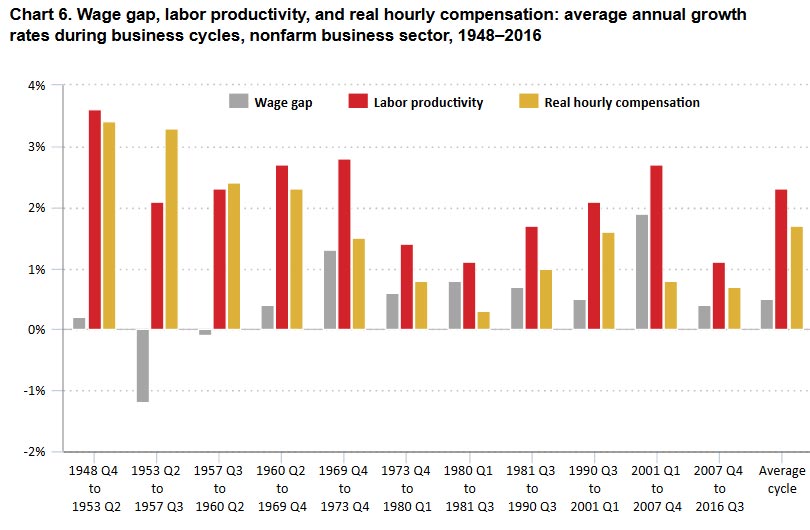

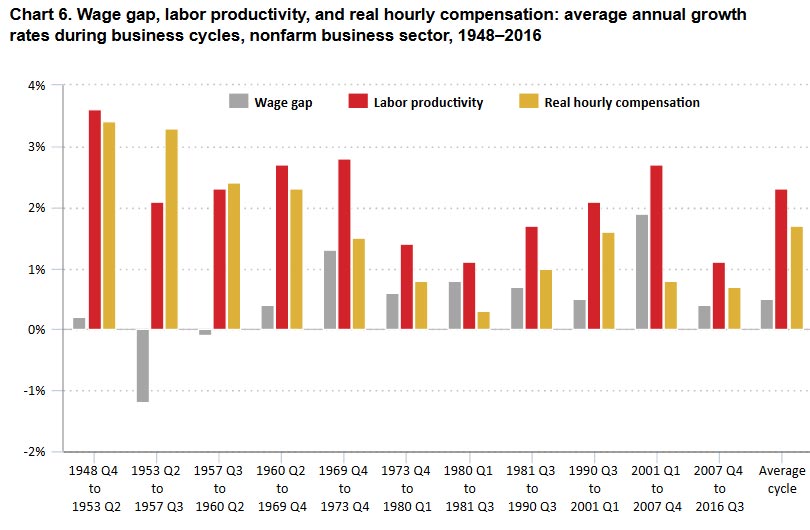

Sluggish productivity growth has implications for worker compensation. As stated earlier, real hourly compensation growth depends upon gains in labor productivity; thus, low labor productivity growth can limit potential gains for workers. During the current business cycle, real hourly compensation (the gold bars in chart 6) has increased 0.7 percent, which is low by historical standards. The rate is lower than the average real hourly compensation growth rate of 1.7 percent observed during other business cycles. The rate is also below the rates of all other cycles, except for a brief six-quarter cycle in the early 1980s. Note also that the low growth rate of the current business cycle is a near-continuation of the similarly low growth rate of the early-2000s cycle (0.8 percent).

There is, however, one interesting difference between the low real hourly compensation growth in the current business cycle and the low real hourly compensation growth in the last cycle. The “wage gap”—defined as the difference in the growth rates of labor productivity and real hourly compensation —for the current cycle is much smaller, at just 0.4 percent. (Compare the gray bars in chart 6.) In fact, the current U.S. business cycle is exhibiting the smallest wage gap since the 1960s. Note, however, that it has been the historically low productivity growth alone that has shrunk the wage gap in the current business cycle, as there were no improvements in real hourly compensation growth relative to the rates from recent cycles.

Looking forward

The historically low rate of labor productivity growth during the current business cycle has limited gains in living standards for Americans during this period. U.S. workers have had to work more hours in order to produce the current supply of goods and services than would have been the case with higher productivity growth. In addition, low productivity growth has limited potential gains in worker compensation and in shareholder profits; these income gains are ultimately dependent upon gains in goods and services produced per hour of work. Americans would be wise to pay attention to productivity trends in coming years, as these trends will figure prominently in our lives and in the lives of future generations.