Federal Reserve Chair Janet L. Yellen spoke at the the Commonwealth Club, San Francisco, California on “The Goals of Monetary Policy and How We Pursue Them.” She reaffirmed the expectation of future rate rises – a few times a year until, by the end of 2019, it is close to its longer-run neutral rate of 3 percent.

https://youtu.be/ktBgb4xHKGY

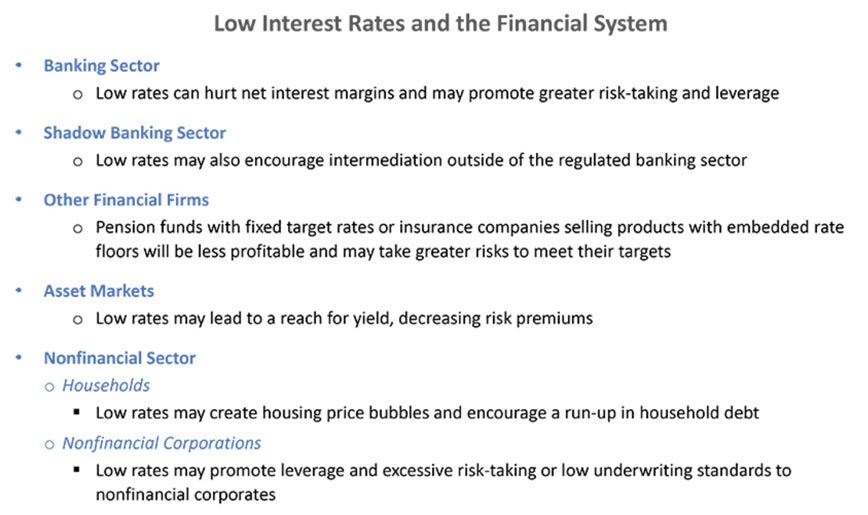

The extraordinarily severe recession required an extraordinary response from monetary policy, both to support the job market and prevent deflation. We cut our short-term interest rate target to near zero at the end of 2008 and kept it there for seven years. To provide further support to American households and businesses, we pressed down on longer-term interest rates by purchasing large amounts of longer-term Treasury securities and government-guaranteed mortgage securities. And we communicated our intent to keep short-term interest rates low for a long time, thus increasing the downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, which are influenced by expectations about short-term rates.

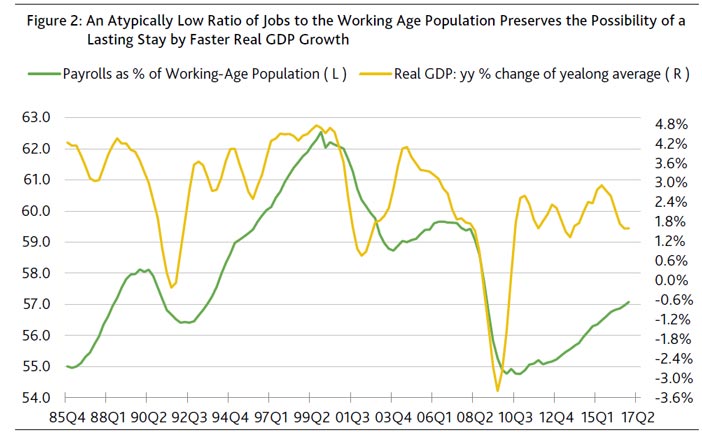

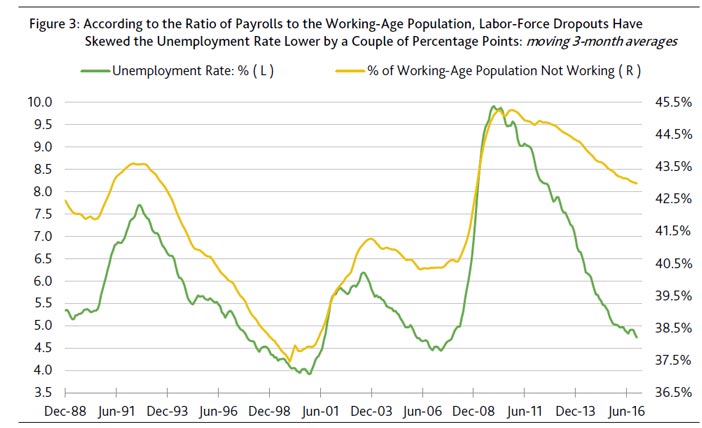

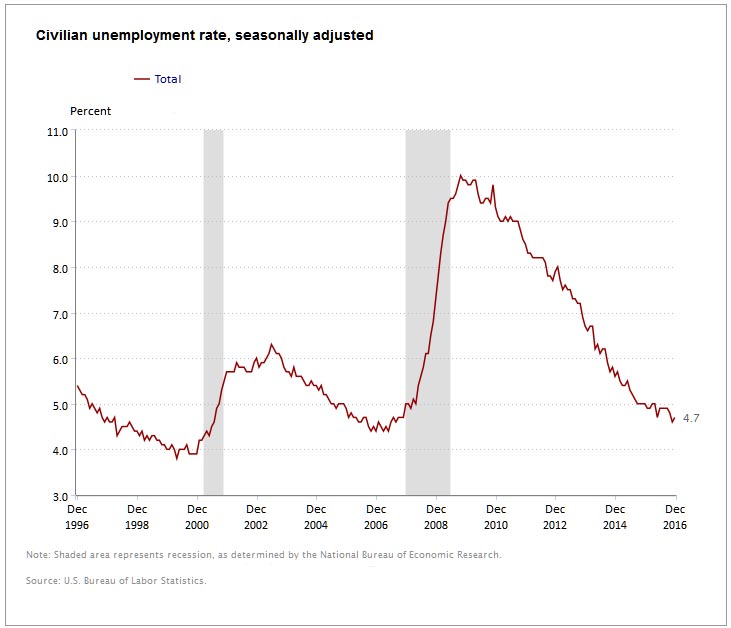

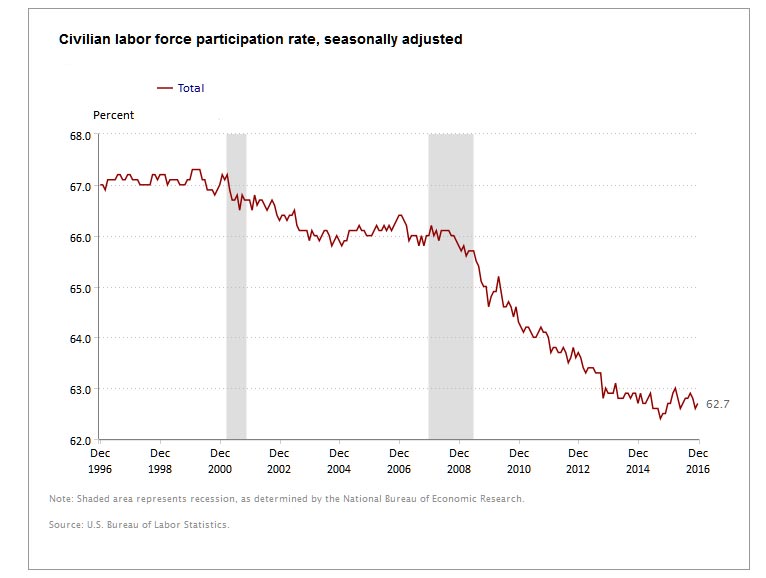

Now, it’s fair to say, the economy is near maximum employment and inflation is moving toward our goal. The unemployment rate is less than 5 percent, roughly back to where it was before the recession. And, over the past seven years, the economy has added about 15-1/2 million net new jobs. Although inflation has been running below our 2 percent objective for quite some time, we have seen it start inching back toward 2 percent last year as the job market continued to improve and as the effects of a big drop in oil prices faded. Last month, at our most recent meeting, we took account of the considerable progress the economy has made by modestly increasing our short-term interest rate target by 1/4 percentage point to a range of 1/2 to 3/4 percent. It was the second such step–the first came a year earlier–and reflects our confidence the economy will continue to improve.

Now, many of you would love to know exactly when the next rate increase is coming and how high rates will rise. The simple truth is, I can’t tell you because it will depend on how the economy actually evolves over coming months. The economy is vast and vastly complex, and its path can take surprising twists and turns. What I can tell you is what we expect–along with a very large caveat that our interest rate expectations will change as our outlook for the economy changes. That said, as of last month, I and most of my colleagues–the other members of the Fed Board in Washington and the presidents of the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks–were expecting to increase our federal funds rate target a few times a year until, by the end of 2019, it is close to our estimate of its longer-run neutral rate of 3 percent.

The term “neutral rate” requires some explaining. It is the rate that, once the economy has reached our objectives, will keep the economy on an even keel. It is neither pressing on the gas pedal to make the car go faster nor easing off so much that the car slows down. Right now our foot is still pressing on the gas pedal, though, as I noted, we have eased back a bit. Our foot remains on the pedal in part because we want to make sure the economic expansion remains strong enough to withstand an unexpected shock, given that we don’t have much room to cut interest rates. In addition, inflation is still running below our 2 percent objective, and, by some measures, there may still be some room for progress in the job market. For instance, wage growth has only recently begun to pick up and remains fairly low. A broader measure of unemployment isn’t quite back to its pre-recession level. It includes people who would like a job but have been too discouraged to look for one and people who are working part time but would rather work full time.

Nevertheless, as the economy approaches our objectives, it makes sense to gradually reduce the level of monetary policy support. Changes in monetary policy take time to work their way into the economy. Waiting too long to begin moving toward the neutral rate could risk a nasty surprise down the road–either too much inflation, financial instability, or both. In that scenario, we could be forced to raise interest rates rapidly, which in turn could push the economy into a new recession.

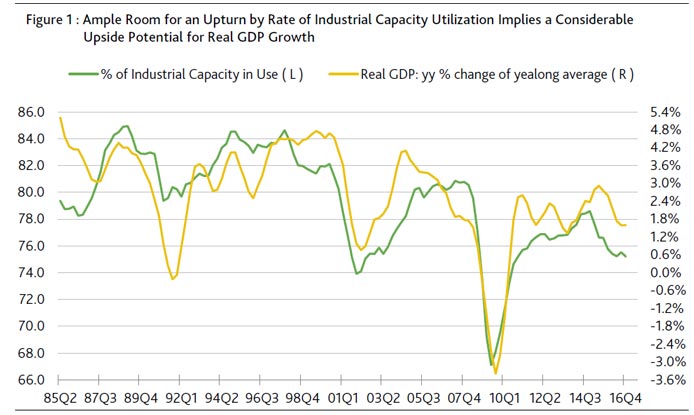

The factors I have just discussed are the usual sort that central bankers consider as economies move through a recovery. But a longer-term trend–slow productivity growth–helps explain why we don’t think dramatic interest rate increases are required to move our federal funds rate target back to neutral. Labor productivity–that is, the output of goods and services per hour of work–has increased by only about 1/2 percent a year, on average, over the past six years or so and only 1-1/4 percent a year over the past decade. That contrasts with the previous 30 years when productivity grew a bit more than 2 percent a year. This productivity slowdown matters enormously because Americans’ standard of living depends on productivity growth. With productivity growth of 2 percent a year, the average standard of living will double roughly every 35 years. That means our children can reasonably hope to be better off economically than we are now. But productivity growth of 1 percent a year means the average standard of living will double only every 70 years.

Economists do not fully understand the causes of the productivity slowdown. Some emphasize that technological progress and its diffusion throughout the economy seem to be slower over the past decade or so. Others look at college graduation rates, which have flattened out after rising rapidly in previous generations. And still others focus on a dramatic slowing in the creation of new businesses, which are often more innovative than established firms. While each of these factors has likely played a role in slowing productivity growth, the extent to which they will continue to do so is an open question.

Why does slow productivity growth, if it persists, imply a lower neutral interest rate? First, it implies that the economy’s usual rate of output growth, when employment is at its maximum and prices are stable, will be significantly slower than the post-World War II average. Slower economic growth, in turn, implies businesses will see less need to invest in expansion. And it implies families and individuals will feel the need to save more and spend less. Because interest rates are the mechanism that brings the supply of savings and the demand for investment funds into balance, more saving and less investment imply a lower neutral interest rate. Although we can’t directly measure the neutral interest rate, it is something that can be estimated in retrospect. And, as we have increasingly realized, it has probably been trending down for a while now. Our current 3 percent estimate of the longer-run neutral rate, for instance, is a full percentage point lower than our estimate just three years ago.

You might be thinking, what does this discussion of rather esoteric concepts such as the neutral rate mean to me? If you are a borrower, it means that, although the interest rates you pay on, say, your auto loan or mortgage or credit card likely will creep higher, they probably will not increase dramatically. Likewise, if you are a saver, the rates you earn could inch higher after a while, but probably not by a lot. For some years, I’ve heard from savers who want higher rates, and now I’m beginning to hear from borrowers who want lower rates. I can’t emphasize strongly enough, though, that we are not trying to help one of those groups at the expense of the other. We’re focused very much on that dual mandate I keep mentioning. At the end of the day, we all benefit from plentiful jobs and stable prices, whether we are savers or borrowers–and many of us, of course, are both.

Economics and monetary policy are, at best, inexact sciences. Figuring out what the neutral interest rate is and setting the right path toward it is not like setting the thermostat in a house: You can’t just set the temperature at 68 degrees and walk away. And, because changes in monetary policy affect the economy with long lags sometimes, we must base our decisions on our best forecasts of an uncertain future. Thus, we must continually reassess and adjust our policies based on what we learn.