Australia should cut its immigration intake, according to Tony Abbott in a recent speech at the Sydney Institute. Abbott explicitly cites economic theory in his arguments: “It’s a basic law of economics that increasing the supply of labour depresses wages; and that increasing demand for housing boosts price.”

But this economic analysis is too basic. Yes, supply matters. But so does demand.

While migration has increased labour supply, it has done so primarily in sectors where firms were starved of labour, and at a time of broad economic growth.

Immigration has put pressure on infrastructure, but our problems are more a function of governments failing to upgrade and expand infrastructure, even as migrants pay taxes.

And while migrants do live in houses, the federal government’s fondness for stoking demand and the inactivity of state governments in increasing supply are the real issues affecting affordability.

The economy isn’t a fixed pie

Let’s take Abbott’s claims about immigration one by one, starting with wages.

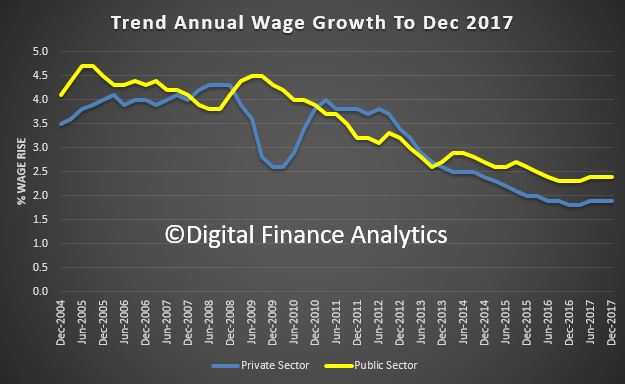

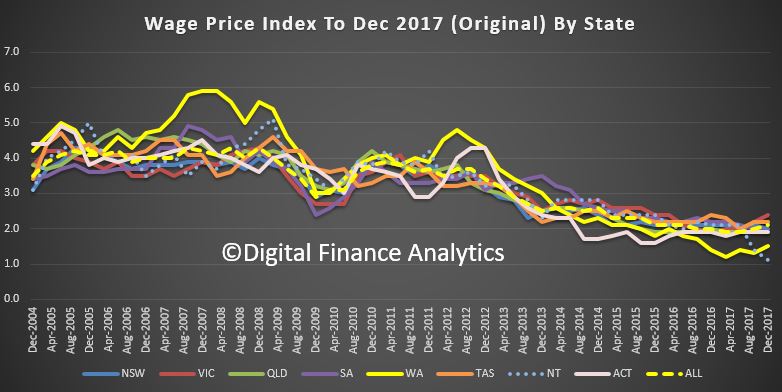

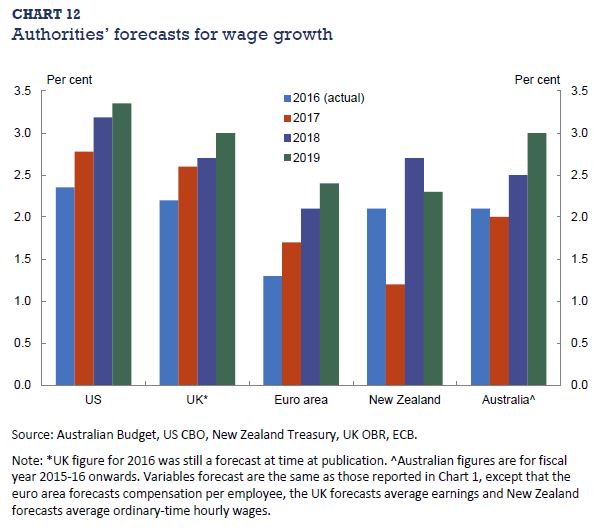

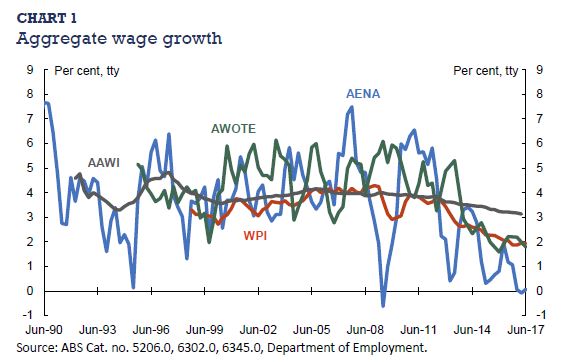

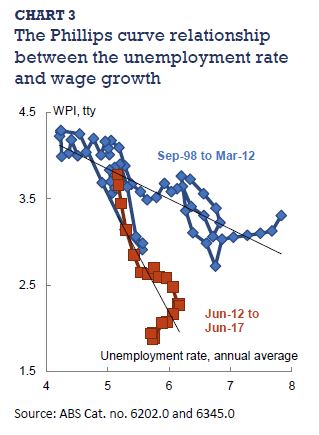

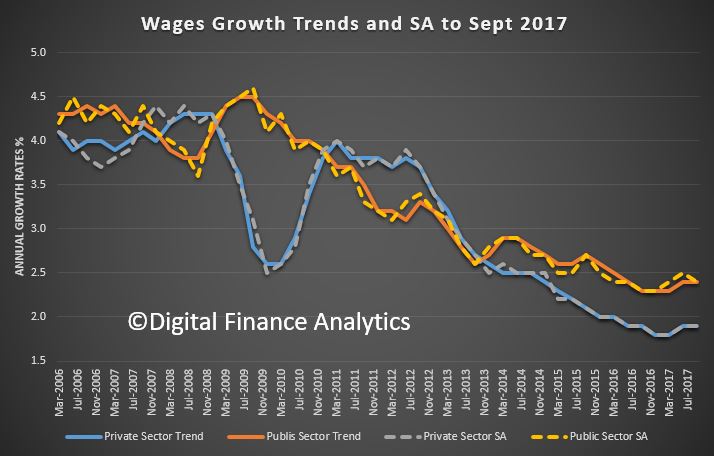

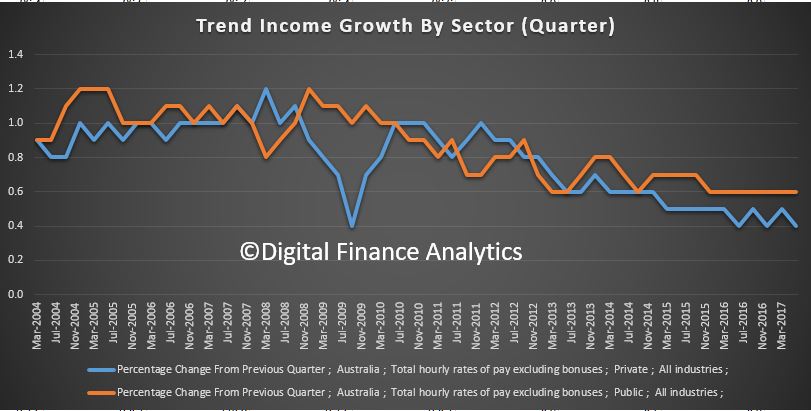

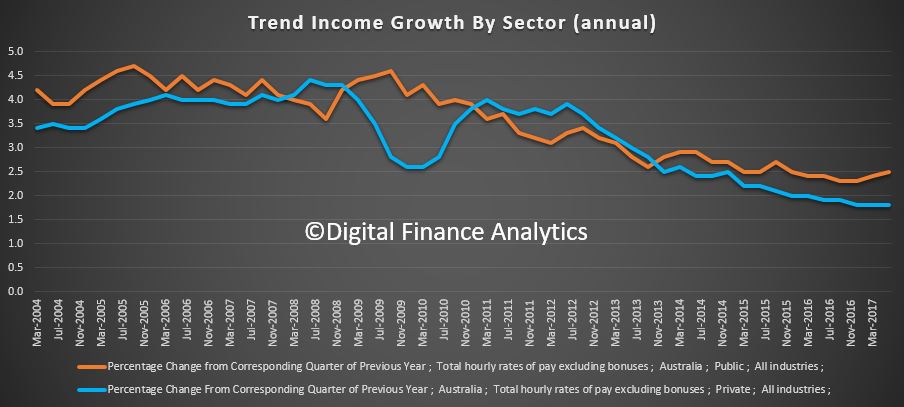

It’s true that if you increase labour supply that, holding other factors that affect wages constant, wages will decline. However, those other factors are rarely constant.

Notably, if the demand for labour is increasing by more than supply (including new migrants), then wages will rise.

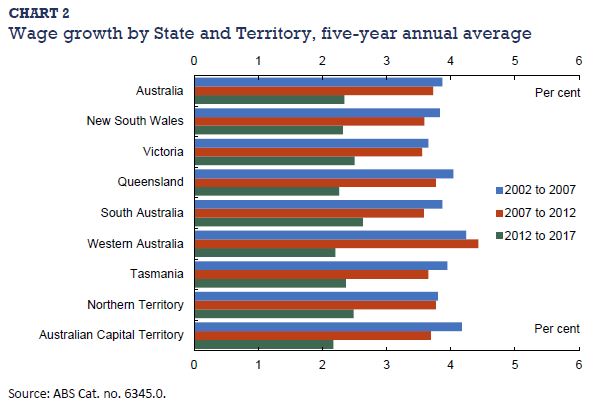

This is a big part of the story when it comes to the relationship between wages and migration in Australia. Large migrant numbers have been an almost constant feature of Australia’s economy since the end of the second world war, if not earlier.

But these migrants typically arrived in the midst of economic growth and rising demand for labour. This is particularly true in recent decades, when we have had one of the longest periods of unbroken growth in the history of the developed world.

In our study of the Australian labour market, we found no relationship between immigration rates and poor outcomes for incumbent Australian workers in terms of wages or jobs.

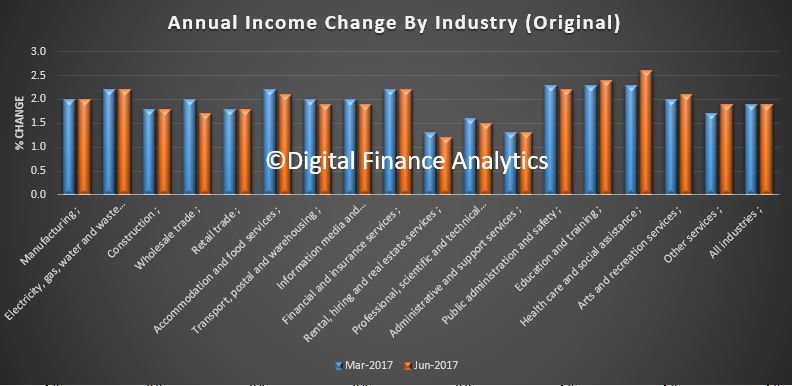

Australia uses a point system for migration that targets skilled migrants in areas of high labour demand. Business is suffering in these areas. Migrants into these sectors don’t take jobs from anybody else because they are meeting previously unmet demand.

These migrants receive a higher wage than they would in their place of origin, and they allow their new employers to reduce costs. This ultimately leads to lower prices for consumers. Just about everybody benefits.

There’s an idea called the “lump of labour fallacy”, which holds that there is a certain amount of work to be done in an economy, and if you bring in more labour it will increase competition for those jobs.

But migrants also bring capital, investing in houses, appliances, businesses, education and many other things. This increases economic activity and the number of jobs available.

Furthermore, innovation has been shown to be strongly linked to immigration. In the United States, for instance, immigrants apply for patents at twice the rate of non-immigrants. And a large number of studies show that immigrants are over-represented in patents, patent impact and innovative activity in a wide range of countries.

We don’t entirely know why this is. It could be that innovative countries attract migrants, or it could be than migrants help innovation. It’s likely that the effect goes both ways and is a strong argument against curtailing immigration.

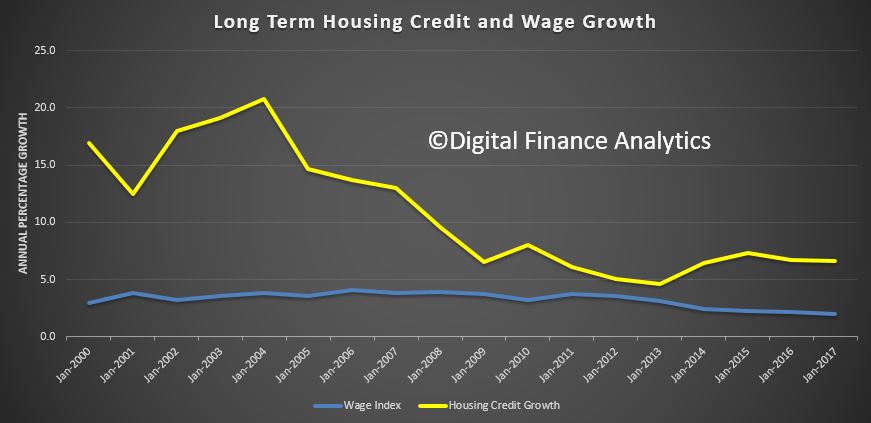

Abbott’s comments are more reasonable in the case of housing affordability because here all other things really are held constant. Specifically, studies show that housing demand is overheated in part by federal government policies (negative gearing and capital gains tax exemptions, for instance) and state governments not doing enough to increase supply.

Governments have responded to high housing prices by further stoking demand, suggesting that people dip into their superannuation, for instance.

In the wake of Abbott’s speech there has been speculation that our current immigration numbers could exacerbate the pressures of automation, artificial intelligence and other labour-saving innovations.

But our understanding of these forces is nascent at best. In previous instances of major technological disruption, like the industrial revolution, the long-run effects on employment were negligible. When ATMs debuted, for example, many bank tellers lost their jobs. But the cost of branches also declined, new branches opened and total employment did not decline.

In his speech, Abbott said that the government needs policies that are principled, practical and popular. What would be popular is if governments across the country could fix our myriad policy problems. Abbott identified some of the big ones – wages, infrastructure and housing affordability.

What would be practical is to identify the causes of these problems and address these directly. Immigration is certainly not a major cause. It would be principled to undertake evidence-based analysis regarding what the causes are and how to address them.

A lot of that has already been done, notably by the Grattan Institute. What remains is for governments to do the politically difficult work of facing the facts.

Authors: Robert Breunig, Professor of Economics, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; Mark Fabian, Postgraduate student, Australian National University