Consumer credit growth has raised concern in some quarters. This type of borrowing – which covers mainstream products such as credit cards, motor finance, personal loans and less mainstream ones such as rent-to-own agreements – has been growing at a rapid 10% a year. What’s been driving this credit growth, and how worried should policymakers be?

For many years regulators have relied on aggregated data from larger lenders to monitor which lenders and products are driving credit growth. These data are useful. But they also have important gaps. For example, they don’t include less-mainstream products that people with low incomes often rely on.

Crucially, such data do not show who is borrowing, or people’s overall debts across different lenders and products. This matters. If people borrow on many products, problems repaying one debt could rapidly spill over to others. Consumer surveys can offer some insights here. But surveys often have limited product coverage, are only available with a lag, and may suffer from misreporting.

To build a better, fuller picture of borrowing, the FCA requested credit reference agency (CRA) data for one in ten UK consumers. CRAs hold monthly data on most types of borrowing – including consumer credit, mortgages, and utilities. These data are really rich, going back six years, and can be studied at many different levels. For example, it is possible to scrutinise individual borrowing across products, or to focus on particular lenders or types of products.

We examined these data to assess possible risks from recent credit growth. This article summarises three particular insights which have emerged from this work:

- Credit growth has not been driven by subprime borrowers;

- People without mortgages have mainly driven credit growth;

- Consumers remain indebted for longer than product-level data implies.

Insight 1: Credit growth has not been driven by subprime borrowers

CRA data enables us to examine the distribution of credit scores among groups of borrowers. This is valuable because credit scores are excellent predictors of which types of borrowers are most likely to default or have high risks of suffering broader financial distress. A lower credit score indicates a greater risk of a person being unable to repay their debt. Those with very low credit scores are often referred to as ‘subprime’ borrowers.

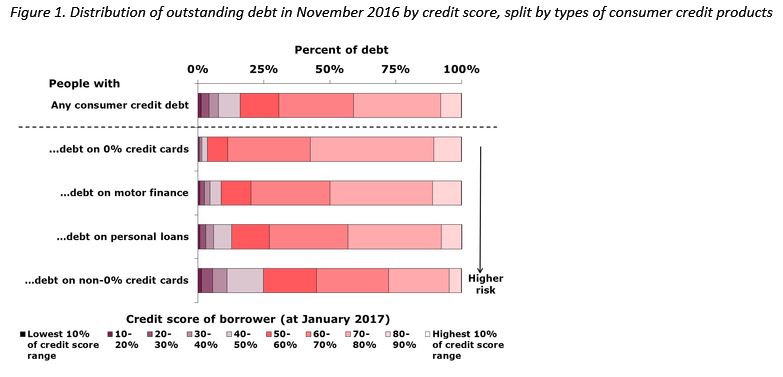

In Figure 1 we show the share of outstanding consumer credit debt (net of repayments) by people’s credit scores. We divide the range of credit scores into ten buckets – the lowest bucket contains people with scores in the bottom tenth of the range (the riskiest borrowers).

Doing so reveals that a small proportion of all consumer credit debt is held by subprime consumers. There are some important differences when we compare people holding different credit products. Borrowing on credit cards with 0% offers and motor finance is concentrated among people with the highest scores. This contrasts with people borrowing on interest-bearing (non-0%) credit cards who more commonly have low scores.

Given motor finance and 0% credit cards have accounted for a majority of consumer credit growth since 2012, this suggests much of the growth is going to the borrowers least likely to suffer financial distress. This story is consistent with high-cost credit markets used by subprime borrowers not rapidly expanding – on the contrary, some are contracting.

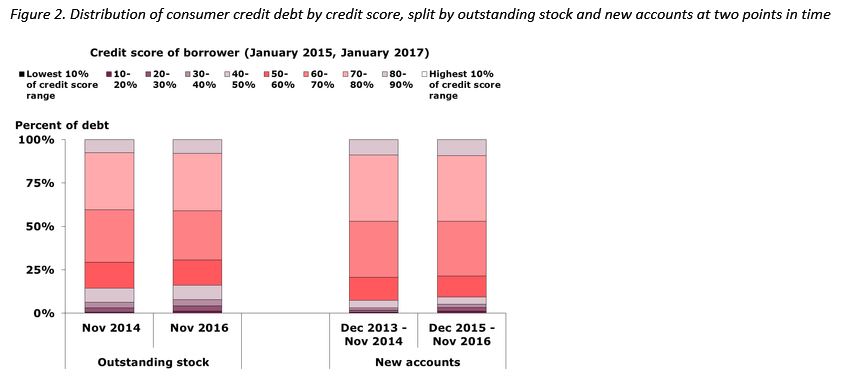

In Figure 2, we turn to how the distribution of borrowing has changed over time. Here we find little difference in credit scores over the recent period of rapid credit growth. This holds when looking at both the outstanding stock and the flow of new borrowing. At face value, this indicates that lenders have not dramatically relaxed their lending standards. But observing a similar credit score distribution when the macroeconomic environment has slightly improved may be better interpreted as a deterioration. The only product where we find an increased concentration of subprime borrowing is interest-bearing credit cards.

History also offers some caution on the relative importance of subprime lending. Recent research on the US mortgage crisis found the pre-crisis growth of subprime borrowing was less dramatic and important to explaining the crisis than earlier studies implied.

Insight 2: People without mortgages have mainly driven credit growth

The recent credit growth has followed a tightening of mortgage lending requirements. Did this tightening have the unintended side-effect of turning mortgage borrowers away from extracting home equity and instead towards consumer credit?

We assess the interaction between these two markets by splitting the growth and stock in borrowing between mortgagors and non-mortgagors. This is shown in Figure 3. About half of outstanding consumer credit is held by those with mortgages. However, this group accounts for a minority of growth in credit balances, with 60% of the growth in credit balances coming from non-mortgagors.

It is comforting that mortgagors do not appear to be bypassing tighter mortgage regulation by amassing consumer credit debt. But a key question going forward is how much of the growth is coming from renters and how much from outright owners.

We know that renters tend to spend a higher share of their income on housing than mortgagors, and so may have less income available for debt repayments. Rapid increases in indebtedness among renters could therefore be a vulnerability.

It is also possible that outright owners are taking out credit, even if they don’t need it. Survey data suggest around 40% of households with consumer credit debt hold savings in excess of such debt. If driven by outright owners, rapid credit growth among non-mortgagors may be less worrying.

Insight 3: Consumers remain indebted for longer than product-level data implies

The Bank has previously argued that lenders’ consumer credit portfolios turn over relatively quickly, reflecting the short terms of consumer credit products (relative to mortgages). In theory, this rapid turnover means that the prudential risks from outstanding consumer credit could quickly increase (or decrease) if lending standards were to deteriorate (or improve).

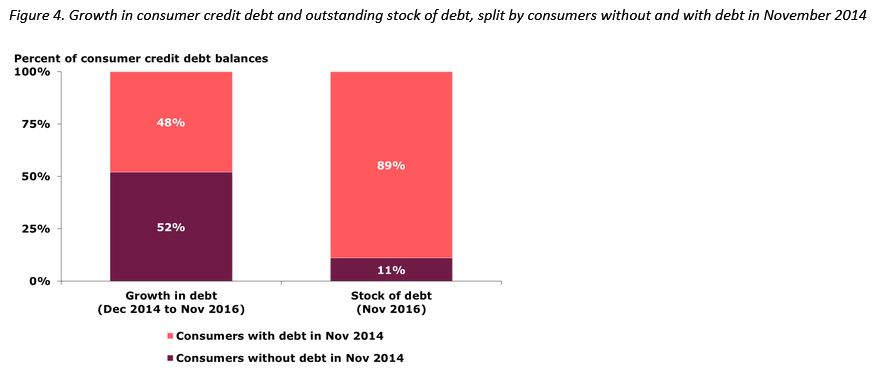

While this may hold from a lender perspective, our analysis tells a different story from consumers’ perspective. We find that although a consumer may clear their debt on one credit product, it is not uncommon for them to remain in debt as they transfer balances, take out new credit products or draw down on existing credit lines (such as credit cards). As shown in Figure 4, 89% of the total outstanding stock of debt in November 2016 was held by people who also owed debt two years earlier. While approximately half of new borrowing is due to ‘new’ borrowers, these people are typically only able to access relatively small amounts of credit and therefore account for a small proportion of the overall stock of debt.

An implication of these findings is that regulators should not become too relaxed when they observe improvements in specific products at particular lenders. Unless the borrower population significantly changes, it is possible that the risk of consumer harm will simply be shifting from one part of the market to another rather than reducing. It is therefore important to regularly examine the financial health of people and their debts holistically using CRA (or similar) data.

Should policymakers be worried?

Credit growth not being disproportionately driven by subprime borrowers is reassuring. As is the lack of evidence that mortgage lending restrictions are pushing mortgagors towards taking on consumer credit.

But vulnerabilities remain. Consumers remain indebted for longer than previously thought. And renters with squeezed finances may be an increasingly important (and vulnerable) driver of growth in consumer credit.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.