Today, in a speech by Chris Aylmer, Head of Domestic Markets Department, RBA, we got an interesting summary of recent developments in the market. This is important, because as at June, the Bank held about $25 billion of these assets under repo as part of their liquidity management operations. In addition, at the same forum, Charles Litterell, EGM APRA discussed the planned reforms to prudential framework for securitisation, highlighting that APRA want to facilitate a much larger, but very simple and safe, funding-only market and also facilitate a capital-relief securitisation market. In both cases, they want to impose a simpler and safer prudential framework than has evolved internationally. The RBA comments are worth reading:

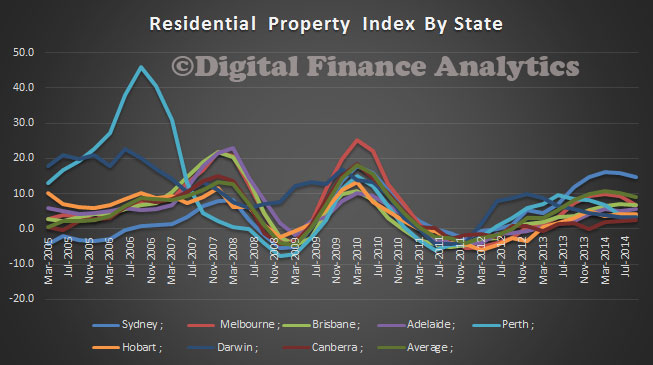

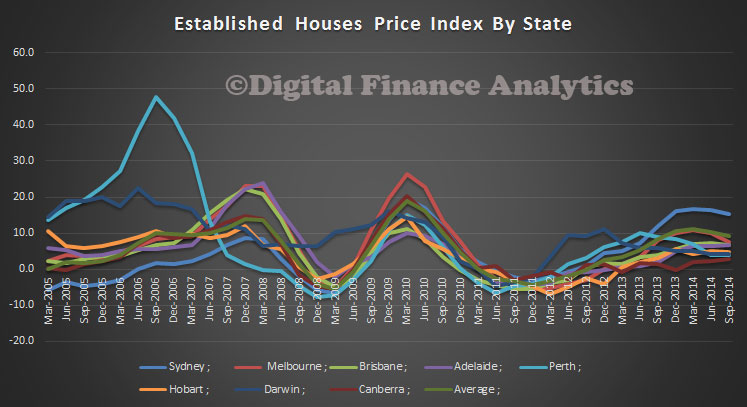

While conditions in global financial markets have improved since the depths of the global financial crisis, the market for asset-backed securities has notably lagged this improvement. Issuance of private-label asset-backed securities in the US is currently equivalent to around 1½ per cent of GDP, compared with an average of around 8 per cent in the first half of the 2000s (Graph 1). Issuance of private-label residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) has been virtually non-existent since 2008. In contrast, issuance of auto loan-backed securities is nearing its pre-crisis level. Issuance of securities backed by student-loans and credit card receivables is also growing, though it remains well below its pre-crisis peak.

Activity in the European securitisation market remains very subdued, with annual issuance placed with investors relative to the size of the economy declining for the fourth year in a row. While the challenging economic conditions on the continent have contributed to this, European authorities have identified a number of other impediments and are developing proposals to address them.[2] In September the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will implement an asset-backed securities purchase program aimed at expanding the ECB’s balance sheet. While this program is not explicitly targeted at reviving the European ABS market, the ECB expects the programme to stimulate ABS issuance.

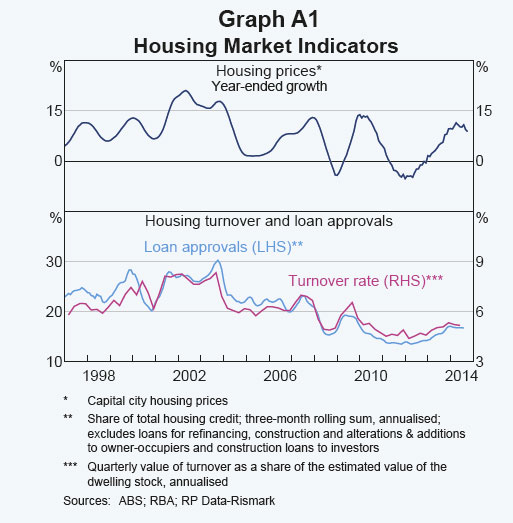

In comparison with its overseas counterparts, the Australian securitisation market, which remains predominantly an RMBS market, has experienced a strong recovery over the past couple of years, albeit not to pre global financial crisis levels. Issuance started to pick up in late 2012, reached a post-crisis high in 2013, and has remained high since then.

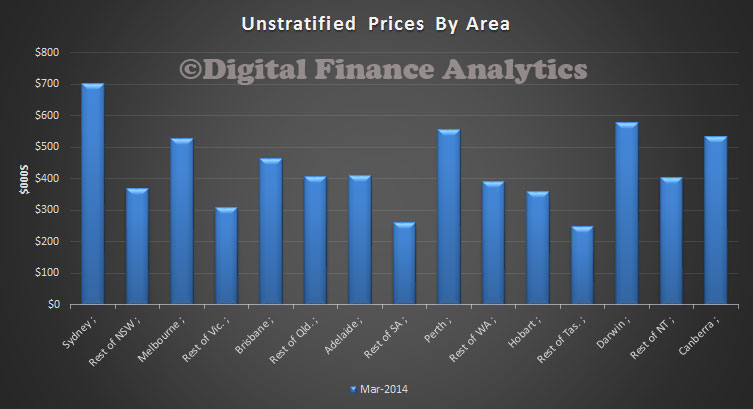

This mainly reflects the strong performance of Australian residential mortgages and the high quality of the collateral pools which are primarily fully documented prime mortgages. While delinquency rates on Australian prime residential mortgages increased after 2007, this increase was a lot less severe than in most other developed economies (Graph 2). Indeed, serious delinquencies in Australia, those of 90 days or longer, remained below 1 per cent and have declined since 2011 to around 0.5 per cent currently. Mortgage prepayment rates, which affect the timing of the payments to the RMBS notes, have also been relatively stable in Australia, resulting in subdued prepayment and extension risk for RMBS investors.

Issuance margins on RMBS continued to tighten throughout this year across all categories of issuers (Graph 3). Banks have been able to place their latest AAA-rated tranches in the market at weighted average spreads of 80 basis points – the lowest level since late 2007. Spreads on the AAA-rated tranches of non-bank issued RMBS have also declined, to around 100 basis points. Investor demand has extended across the range of tranches, with a significant pick-up reported in demand for mezzanine notes. As a result, a number of issuers have priced their mezzanine notes at some of the tightest spreads since 2007.

Similar to last year, RMBS issuance this year has mainly originated from the major banks (Graph 4). Indeed, issuance by the major banks is on par with their issuance prior to the global financial crisis. Issuance by other banks has also been robust this year, although it is still well below pre-crisis levels when these issuers accounted for around 40 per cent of the market.

Mortgage originators have been active this year, although their issuance has predominantly been of prime RMBS. Mortgage originators have issued only $1.6 billion of non-conforming RMBS in 5 transactions so far this year. The number of mortgage originators active in the market in the past two years has increased relative to the period from 2009 to 2012.

They are an important presence in the market. In the period preceding the global financial crisis, mortgage originators took advantage of innovations in the packaging and pricing of risk. In doing so, they were able to undercut bank mortgage rates. The banks responded and spreads on mortgages declined markedly. While a number of large mortgage originators have exited the market, the presence of mortgage originators promotes competition in the mortgage market.

Issuance of asset-backed securities other than RMBS has generally been in line this year with previous years. Issuance of commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and other ABS this year has been around $5 billion, compared with an average of about $6 billion over the three preceding years.

The investor base in Australian ABS has continued to evolve (Graph 5). The stock of RMBS held by non-residents has been relatively steady since late 2010 suggesting that non-residents have been net buyers of Australian ABS. The strong performance of Australian RMBS and lack of issuance elsewhere may have been an important driver behind the participation of foreign investors. There has been a pick-up in RMBS holdings by Authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) – they now hold just under 40 per cent of marketed ABS outstanding – with the major banks accounting for much of the increase.

Holdings of ABS by real money domestic investors have gradually declined, to the point where these investors, in aggregate, now hold less than a quarter of what they held four years ago. The longer-term sustainability of the Australian securitisation market may well depend on increasing participation in the market by domestic real money investors.

One of the key structuring developments since mid 2007 has been the increase in credit subordination provided to the senior AAA-rated notes. This primarily reflects decreased reliance by the major banks on lenders mortgage insurance (LMI) support in their RMBS. This trend has been driven by investor preference for detaching the AAA-rating on the senior notes from the ratings of the LMI provider.

The increased subordination in the major banks’ RMBS has been to a level in excess of that required to achieve a AAA-rating without LMI support. This mitigates the downgrade risk owing to changes in ratings criteria. In contrast, other categories of RMBS issuers have continued to use LMI to support their structures, allowing them to achieve AAA-ratings on a larger share of their deals.

The RBA highlighted that “the risk management and valuation of ABS collateral is obviously an analytically intensive process, requiring considerable information about the security and the underlying assets. Over time we will further develop pricing and margins that reflect the specifics of the asset-backed security and its collateral pool. This could, for example, take the form of credit risk models of the collateral pool which take into account characteristics such as geographic concentrations, delinquencies and loan-to-value ratios. These collateral credit models will be combined with structural security models to calibrate margins specific to the security that reflect its projected behaviour under stress scenarios”.