Films like The Big Short have shaped many people’s view of residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS).

Like all types of investing, RMBS come with their share of risks and they’re easy for Hollywood to dramatise. However, James Austin, chief financial officer of local non-bank lender Firstmac, says RMBS unfairly carry the load for everything that went wrong in the US in 2007.

“The reality is that in the US, RMBS was simply the tool,” says Austin. “It’s a bit like a builder blaming his hammer. In actual fact it’s the loans themselves and the way those loans were written that were the problem, not the underlying structure or tool.”

The lack of regulation in US markets prior to the global financial crisis also contributed to the mishandling of mortgage backed securities. This is important to understand when considering RMBS in Australia, which is a very different market.

The scoop on securities

RMBS serve two main functions: on the one hand they give investors access to the mortgage market, while on the other they help financial institutions free up or raise capital. Home loans are traditionally private transactions that stay on a lender’s balance sheet for the duration of the mortgage, which means all the capital that’s paid remains tied up.

However, by pooling many loans together into a ‘security’, which is basically a bond (or IOU) that’s legally backed by home loans, this capital is moved off the lender’s books and made available. So, in short, RMBS are debt securities that investors can purchase from financial firms, with a view to earning interest on the entire pool.

There are also different classes of securities called tranches, which are just packages of loans. These let investors target a segment of home loans based on their quality and duration.

“The bond will have a rating from the rating agency, so as an investor you can trade off your risk appetite with the return you want to get,” says principal of consultancy Digital Finance Analytics, Martin North. “For example, you might decide to go for a junk bond [high risk – high yield] with a very a high coupon, but if people in that tranche started defaulting on their mortgages, then that bond would become worthless.

“Whereas a triple-A [low risk – low yield] bond puts you right at the top of the tree and you’d need to have major ruptures in the marketplace to lose your coupon.”

As such, returns on RMBS will vary depending on both the size of the issuance and the tranche you buy into. For example, Firstmac recently completed a $500m sale of RMBS, which produced about a 3.35% return in its AAA tranche, over a weighted average life of around 3-4 years.

Meanwhile, Firstmac’s High Livez RMBS fund, which is a retail fund available to regular investors, holds RMBS from big banks such as Commonwealth Bank and Westpac and has achieved a total return of 6.66% per year since inception in 2011, according to Firstmac. It’s worth noting that RMBS yields can be impacted by general market appetite, interest rate levels and the cost of insurance that’s put in place by the issuing company, among other things.

Who’s investing?

Given that many lenders use RMBS, investors in them can span a number of groups, including super funds, insurance companies, high net wealth investors and the government. The Big Short touched on several of these investors, including government sponsored mortgage company, Fannie Mae.

In Australia, the government’s support of the RMBS market is equally important. According to Austin, RMBS were funding $50-60 billion worth of Australian home loans per year before the GFC, which equated to about 20-25% of all home loans. This was almost completely erased by the financial crisis however, and that’s when the Australian Government stepped in with a $20 billion programme to support RMBS.

Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s says that RMBS now represent around 10% of housing credit funding locally and has been trending upward since 2009.

Risky business

Many local experts don’t see securities markets of other countries as all that comparable to Australia because of our regulatory framework, which is crucially supported by lender’s mortgage insurance on loans issued for more than 80% of the purchase price. This helps to maintain a lower level of mortgage arrears and historically low numbers of defaults.

S&P says that Australian regulators focus on prudent lending standards and this also provides an important safeguard to the local market. There are other factors that make RMBS favourable to local investors, such as Australia’s strong migration levels, which underpin the constant demand for housing, and an ongoing shift away from other financial sectors like mining, says S&P.

At the same time, Australian borrowers must pass strict credit checks by lenders and show other assets in their name, whereas some US home loans are non-recourse, meaning that the only security for RMBS investors in those instances are the properties themselves. When homes plummeted in value during the GFC, many borrowers just walked away.

“In Australia you can’t walk away,” says Austin. “They [authorities] will still come after your other assets or garnish your wages. Australians pay their mortgages, as a result.”

Additionally, Australian loans are only serviced by the lender and are not passed onto other parties, the way they typically are in the US.

Where are RMBS now?

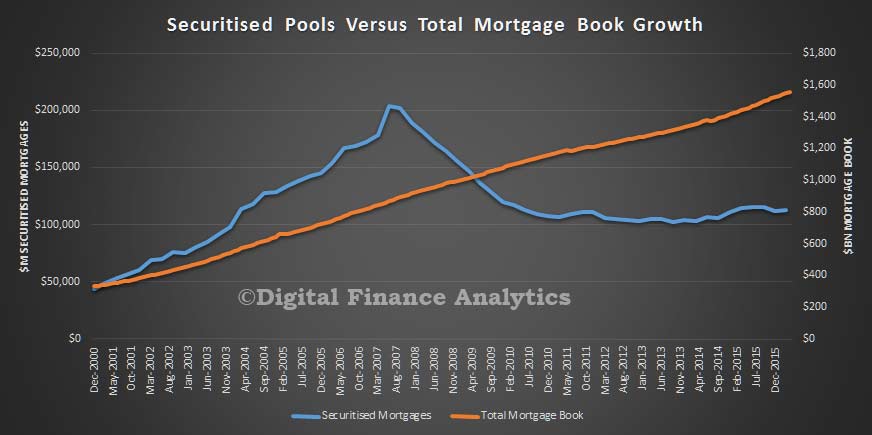

North says that up until the GFC there was momentum in securitised mortgages in Australia, but that since 2008 issuances have been relatively modest.

Still, at the end of 2015 S&P reported a significant upswing in the issuance of RMBS over the last two years, due to a variety of factors that include increased domestic and offshore investor interest. Overall, more than $20bn worth of RMBS were issued in Australia last year, as per S&P.

By contrast, this year hasn’t started as strongly, with around $5bn issued as of April 30, S&P reports. Managing director and lead analytical manager at S&P, Kate Thomson says that global uncertainty in response to China’s slowdown, as well as the Brexit referendum in the UK, APRA’s proposals for APS 120 and Basel regulations, Transparent and Standardised (“STS”) Securitisations in Europe, and amendments to the EU Capital Requirements Regulation have all impacted RMBS growth lately.

Nonetheless, there are still major players in Australia, including Commonwealth Bank and Macquarie Bank, which are the top two RMBS issuers over the 12 month to March 31, S&P says. Other notable issuers include Westpac, ING and Citigroup, and smaller firms like Pepper Home Loans, Firstmac, Heritage Bank and Liberty Bank.

So there’s still a range of opportunities in RMBS for different investors and while it may not be as prominent a vehicle as it once was, the concept is still interesting, says North.

“It [RMBS] manages capital differently, turning cash flow into capital,” he says. “And so if the market ever freed up, it could reassert itself.”

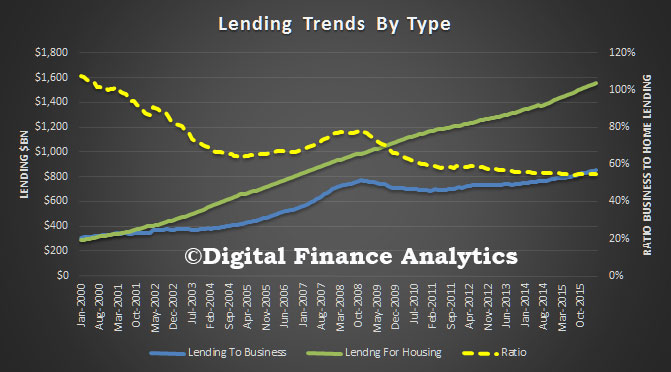

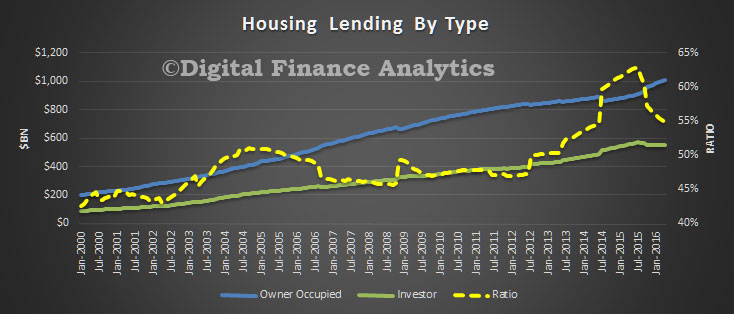

There are many reasons why things have changed. The finance sector has been deregulated, larger companies can now access capital markets directly and so do not need to borrow from the bank, generous tax breaks (negative gearing and capital gains) have lifted the demand for loans for housing investment, and the Basel capital ratios now make it much cheaper for banks to lend against secured property compared to business. In fact the enhanced Basel ratios were introduced in the early 2000’s and this is when we see lending for housing taking off.

There are many reasons why things have changed. The finance sector has been deregulated, larger companies can now access capital markets directly and so do not need to borrow from the bank, generous tax breaks (negative gearing and capital gains) have lifted the demand for loans for housing investment, and the Basel capital ratios now make it much cheaper for banks to lend against secured property compared to business. In fact the enhanced Basel ratios were introduced in the early 2000’s and this is when we see lending for housing taking off. We therefore argue that whilst the election focus has been on proposed cuts to negative gearing and capital gains versus a company tax cut, the root cause issue is still ignored. And it is a biggie. The international capital risk structures designed to protect depositors, is actually killing lending to business, because it makes lending for housing so much more capital efficient. Whilst recent changes have sought to lift the capital for mortgages at the margin, it is still out of kilter. As a result, banks seek to out compete for mortgages and offer discounts and other incentives to gain share, whilst lending to business is being strangled. This is exacerbated by companies being more risk adverse, using high project hurdle thresholds (despite low borrowing rates) and smaller businesses being charged relatively more – based on risk assessments which are directly linked to the Basel ratios. Our SME surveys underscore how hard it is for smaller business to get loans at a reasonable price.

We therefore argue that whilst the election focus has been on proposed cuts to negative gearing and capital gains versus a company tax cut, the root cause issue is still ignored. And it is a biggie. The international capital risk structures designed to protect depositors, is actually killing lending to business, because it makes lending for housing so much more capital efficient. Whilst recent changes have sought to lift the capital for mortgages at the margin, it is still out of kilter. As a result, banks seek to out compete for mortgages and offer discounts and other incentives to gain share, whilst lending to business is being strangled. This is exacerbated by companies being more risk adverse, using high project hurdle thresholds (despite low borrowing rates) and smaller businesses being charged relatively more – based on risk assessments which are directly linked to the Basel ratios. Our SME surveys underscore how hard it is for smaller business to get loans at a reasonable price.