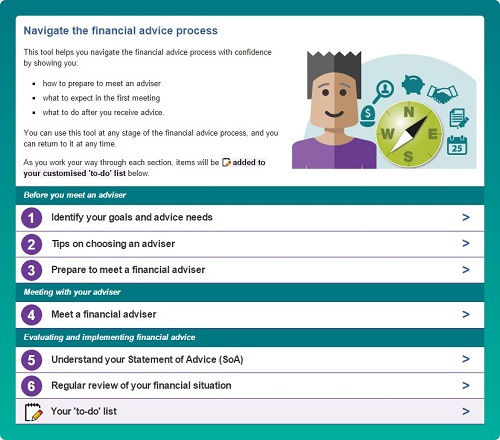

Many Australians dream of starting their own businesses. But they face restrictions on where they can access startup capital. In Australia you must be certified as a “sophisticated investor” to invest in risky, early stage ventures that cannot yet comply with costly disclosure requirements.

A “sophisticated investor” is someone with an income of at least A$250,000 per annum or assets worth A$2.5 million. But this qualification not only discriminates against some investors, it is a very limited view of what it means to be “sophisticated”. It also ignores recent changes in how companies interact with an important group of early investors – their customers. Even more, it robs startups of valuable capital.

The argument against “sophistication”

The argument for this restriction is that investing in private companies with unregulated disclosures is risky. They are not subject to the same requirements of a public company and are potentially more difficult for a layman to evaluate. “Unsophisticated investors” should just stick to publicly listed investments because they are less risky and more transparent.

But there’s nothing particular about having money that makes you a good investor and investors get shortchanged in public markets as well.

In particular, it is well documented that, on average, shares sold to the public through an IPO significantly underperform other investments in the long-run. Even when a high quality IPO does come to the market, unsophisticated investors will struggle to get a meaningful allocation, while wealthy, well-connected investors end up with most of what they ask for.

The academic literature refers to this as the “winner’s curse”, whereby unsophisticated investors only receive shares in an IPO when sophisticated investors think it’s a lemon.

Many startups have a unique relationship with customers

But companies also have greater intimacy with their customers than ever before. Micro-investing startup Acorns recently sought to raise A$6 million in a private share issue, at least partially from its estimated 160,000 Australian users. Acorns’ users are reported to have already pledged more than A$1 million to help the startup replenish its cash and pursue further growth opportunities.

Acorns may be slightly unusual in being able to raise this money, as it is itself an investing app. It helps its users build wealth by saving “spare change” and investing this money for them. So its client base is at least familiar with the tenets of investing.

But Acorns’ ability to tap its user base as a source of capital also challenges the notion that only “sophisticated” investors are suitably qualified to participate in early stage deals. Acorns’ users are typically young tech savvy millennials who are unlikely to pass the sophisticated investor test (which is probably why they are using the app). Yet, because of their interaction with the app, these users have unique insights in evaluating Acorns’ prospects.

It raises questions as to whether the distinction between “sophisticated” and “unsophisticated” investors remains relevant in the world of app based tech startups. These startups often have aggressive go-to-market business models that attempt to capture as many users as possible relatively early in their life. Would someone that is cash rich have a better understanding of this business than a customer or user of it?

In making an early stage investment decision a “sophisticated” investor could try to determine whether an app solves a significant problem in its user’s life and thus how deeply a user will engage with it. But predicting the behaviour of app users is inherently difficult. So who better to predict it than the users themselves?

Discriminating against certain investors costs everyone

Under the current rules, a lot of “unsophisticated” users are denied access to such investment opportunities because they are simply not wealthy enough. This robs investors of an opportunity and startups of a potential source of capital. Even more, we all could lose as companies that create incredible products struggle or die for lack of funds.

For startups, drawing on customer support, as Acorns has done, would provide a source of capital that does not carry the costs and conditions that are typically attached to angel and venture capital funding. For small investors it gives them direct access to some potentially very lucrative (but very high-risk) investments that otherwise would be impossible or very costly to access.

Democratising the way startups are financed could create an environment whereby entrepreneurs, small investors and the economy as a whole all benefit from financing new and interesting endeavours. But it all starts with re-conceptualising the current arbitrary notion of “sophistication”.

, Associate Professor, UNSW Australia