At first blush the news at home and abroad appears to be steering us towards our most risky – scenario 4 outcome, where global financial markets are disrupted and home prices fall by 20-40 percent or more as confidence wains.

Some would call this GFC 2.0. So let’s looks at the evidence.

Some would call this GFC 2.0. So let’s looks at the evidence.

In Australia, as we predicted, a massive class action lawsuit is being planned on behalf of “Australian bank customers that have entered into mortgage finance agreements with banks since 2012”.

Law firm Chamberlains has been appointed to act in the planned class action lawsuit, which has been instructed by Roger Donald Brown of MortgageDeception.com in the action that aims to represent various Australian bank customers that are “incurring financial losses as a result of entering into mortgage loan contracts with banks since 2012”.

As the AFR put it – Lawyers’ representing up to 300,000 litigants are planning an $80 billion action against mortgage lenders, mortgage brokers and financial regulators in a class action that would dwarf previous actions. Roger Brown, a former Lloyds of London insurance broker, said he already has about 200,000 borrowers ready to join the action and has $75 million backing from UK and European investors. There has been a scam, he said about mortgage lending to Australian property buyers. “But the train has hit the buffers and there needs to be recompense.

As we discussed before, if loans made were “unsuitable” as defined by the credit legislation, there is potential recourse. This could be a significant risk to the major players if it gains momentum. And more will likely join up if home prices fall further and mortgage repayments get more difficult. But we think individuals must take some responsibility too!

Next, we now see a number of the major media outlets starting to blame the Royal Commission for the falls in home prices, tighter lending standards and even damage to the broader economy. Talk about shoot the messenger. The fact is we have had years of poor lending practice, and poor regulation. But the industry and regulators kept stumn preferring to enjoy the fruits of over generous lending. The Royal Commission is doing a great job of exposing what has been going on. In fact, the reaction appears to be that what had been hidden is now in the sunshine, and it is true the sunlight is the best disinfectant. Structural malpractice is being exposed, some of which may be illegal, and some of which certainly falls below community expectations. But let’s be clear, it’s the poor behaviour of the banks and the regulators which have placed us in this difficult position. Hoping bad lending remans hidden is a crazy path to resolution. At least if the issues are in the open they stand a chance of being addressed.

But it is also true that just a lax lending allowed households to get bigger mortgages than they should, and bid home prices higher, to be benefit of the banks, and the GDP out-turn, the reverse is also true. Tighter lending will lead to less credit being available, which in turn will translate to lower home prices, and less book growth for the banks. But do not lay this at the door of the Royal Commission. They are actually doing Australia a great service, in a most professional manner.

But that does not stop the rot. UBS came out today with an update saying that the housing market is slowing, with house prices falling and credit conditions tightening. Given the number of headwinds the market is facing; many investors are now questioning whether the housing correction could become disorderly. We expect credit growth to slow sharply and believe the risk of a Credit Crunch is rising.

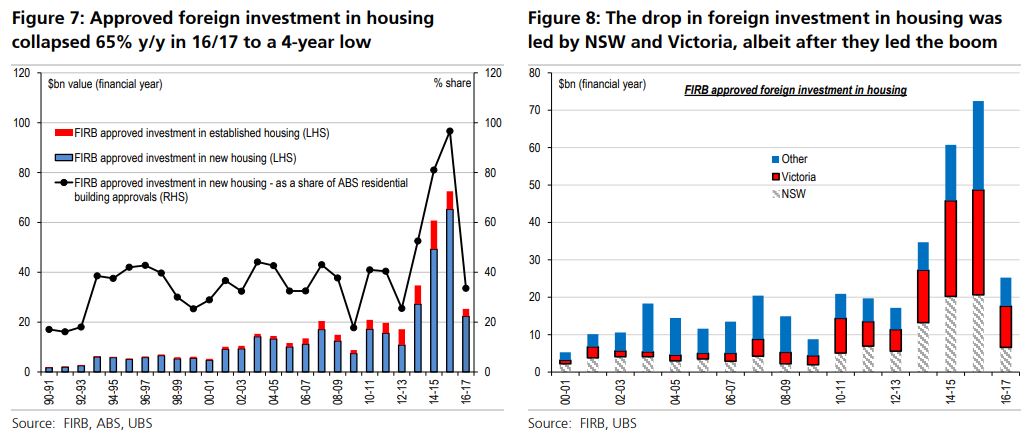

They walk through the main areas, including tighter lending, interest only loans and foreign buyers. Specifically, they highlight that approved foreign investment in housing is down -65%. The Foreign Investment Review Board just released data for 16/17. The value of approvals to buy residential housing collapsed 65% y/y to $25bn in 16/17, the lowest level since 12/13, and mostly reversing the prior ‘super boom’. The fall was across both new (-66% to $22bn) and established housing (-59% to $3bn) – led by total falls in NSW (-66% to $7bn) and Victoria (-61% to $11bn.

They walk through the main areas, including tighter lending, interest only loans and foreign buyers. Specifically, they highlight that approved foreign investment in housing is down -65%. The Foreign Investment Review Board just released data for 16/17. The value of approvals to buy residential housing collapsed 65% y/y to $25bn in 16/17, the lowest level since 12/13, and mostly reversing the prior ‘super boom’. The fall was across both new (-66% to $22bn) and established housing (-59% to $3bn) – led by total falls in NSW (-66% to $7bn) and Victoria (-61% to $11bn.

They say that the collapse in 16/17 may be overstated because of the introduction of application fees in Dec-15 – meaning the fall in transactions is less pronounced. But, there is still likely to have been a drop in transactions, reflecting more structural factors including – the lift in taxes on foreigners; domestic lenders tightening standards for foreign buyers (effectively no longer lending against foreign sources of income or collateral); as well as tighter capital controls especially from China.

Their base case is for a small fall in prices ahead, and assumes house prices fall by 5%+ over the coming year and that bad and doubtful debts increase only modestly given the current very benign credit environment. but they also talk about a downside scenario which reflects a more disorderly correction in the housing market (ie a Credit Crunch) and could result in approximately 40% reduction in major bank share prices. This is likely due to credit growth falling more substantially, by ~2-3% compound and credit impairment charges rising significantly as the credit cycle turns. This scenario would put pressure on bank NIMs. Litigation risk from class actions for mortgage misselling is also a tail risk. Dividends would need to be cut in this scenario. Given the leverage in the banking system, accurately predicting the extent of a downturn is very difficult, as was seen in 2008.

And the reason they still hold to their milder view is the expectation that the Government will step in to assist, and slow the implementation of recommendations from the Royal Commission. To quote Scott Morrison on 2GB radio on 23d March.

If banks stop lending, then what do people think that is going to mean for people starting businesses or getting loans or getting jobs or all of this. In the budget papers, the Treasury have actually highlighted this as a bit of a risk with the process we are going through. We have got to be very careful. These stories are heartbreaking, I agree, but we have to be also very cautious about, well, how do we respond to that. What is the right reaction to that? Is it to just throw more regulation there which basically constipates the banking and financial industry which means that people can’t start businesses and people can’t get jobs, people can’t get home loans. Or do we want to move to a smarter way of how this is all done and I think in the era of financial technology in particular there are some real opportunities there. We are going to continue to listen and carefully respect the royal commission, not prejudge the findings, but be very careful about any responses that are made because this can determine how strong an economy we live in over the next ten years and whether people get jobs and start businesses.

But in essence, expect some unnatural acts from the Government to try to keep the bubble going a little longer. All bets are off the other side of the election.

And the third risk, and the one which takes us closest to GFC 2.0 is what is happening in Italy. I am not going to go back over the history, but after months of wrangling, Italy’s political crisis has a hit an impasse, with new elections now increasingly likely. The country faces an institutional crisis without precedent in the history of the Italian republic. Its implications extend well beyond Italy, to the European Union as a whole.

Since an election on March 4, there have been endless vain attempts to form a government – with the likely outcome changing every 24 hours. By mid-May, the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the League, both populist parties, had come together to draft a programme for government featuring tax cuts and spending plans. But it sent shivers down the spines of those contemplating Italy’s public debt – running at over 130% of GDP – and threatened the stability of the eurozone.

The appointment of Carlo Cottarelli, a former official from the International Monetary Fund, as prime minister on May 28 was merely a stop-gap measure until fresh elections in the autumn. His government will almost certainly fail to win the necessary vote of confidence required of all incoming governments upon taking office. This means that it will be unable to undertake any legislative initiatives that go beyond day-to-day administration.

ITALY’S president, Sergio Mattarella had originally planned to put a former IMF economist, Carlo Cottarelli, at the head of a government of technocrats, tasked with steering the country back to the polls after the summer. But Mr Mattarella was reportedly considering changing tack after meeting Mr Cottarelli on May 29th amid growing evidence of support in parliament for an earlier vote. Not a single big party has declared its readiness to back Mr Cottarelli’s proposed administration in a necessary vote of confidence.

So the president is expected to decide on May 30th whether to call a snap election as early as July in an effort to resolve a rapidly deepening political and economic crisis that has sent tremors through global financial markets. There was also concern that the populist parties could win a bigger parliamentary majority in the new election, creating a bigger risk for the future of the eurozone.

In a sign of investors’ concern, the yield gap between Italian and German benchmark government bonds soared from 190 basis points on May 28th to more than 300. The governor of the Bank of Italy, Ignazio Visco, warned his compatriots not to “forget that we are only ever a few steps away from the very serious risk of losing the irreplaceable asset of trust.”

The yield on two-year debt has risen from below zero to close to 2% and Italy’s 10-year bond yields, which is a measure of the country’s sovereign borrowing costs, breached 3 per cent on Tuesday, the highest in four years. At the start of the month they were just 1.8 per cent. Italy’s sovereign debt pile of €2.3 trillion is the largest in the eurozone

The Italian stock market was also down 3 per cent on Tuesday, and has lost around 13 per cent of its value this month.

But these movements need to be put in some context. The Italian stock market is still only back to its levels of last July, after experiencing a strong bull run since later 2016.

In 2011 and 2012 Italian bond breached 7 per cent and threatened a fiscal crisis for the government in Rome. Yields are still some distance from those extreme distress levels.

George Soros was quoted in the FT:

The EU is in an existential crisis. Everything that could go wrong has gone wrong,” he said. To escape the crisis, “it needs to reinvent itself.” Mr Soros said tackling the European migration crisis “may be the best place to start,” but stressed the importance of not forcing European countries to accept set quotas of refugees. He said the Dublin regulation — which decides which nation is responsible for processing a refugee’s asylum status, largely based on which country the individual first enters — had put an “unfair burden” on Italy and other Mediterranean countries, “with disastrous political implications.” While austerity policies appeared initially to have been working, said Mr Soros, the “addiction to austerity” had harmed the euro and was now worsening the European crisis. US president Donald Trump’s exit from the nuclear arms deal with Iran and the uncertainty over tariffs that threaten transatlantic trade will harm European economies, particularly Germany’s, he said, while a strong dollar was prompting “flight” from emerging market economies. “We may be heading for another major financial crisis,” he said. Meanwhile, years of austerity policies had led working people to feel “excluded and ignored,” sentiment that had been exploited by populist and nationalistic politicians, said Mr Soros. He called for greater emphasis on grassroots organisations to meaningfully engage with citizens.

To play devil’s advocate, if Italy were to leave the Eurozone, the Lira would drop, hard. Most probably Italy would default on debt, and this would hit the Eurozone banks hard, especially those in German and French banks will be hit hard and they are saddled with about half the outstanding debt. Just like in the GFC a decade back, global counter-party bank risk will rise, and this time sovereign are involved, so it may go higher. The US Dollar will run hot, and there will be a flight to quality, tightening the capital markets, lifting rates and causing global stocks and commodities to crash, possibly a recession will follow.

In Australia, the dollar would slide significantly, fuelling stock market falls and a further drop in home prices, leading to higher levels of default, and recession, despite the Reserve Bank cutting rates and even trying QE.

Now the financial situation in Italy at the moment, a far cry from the height of the eurozone crisis in 2012, when it really did look possible that weaker member states would be imminently forced to default and the single currency would collapse. Then, that situation was finally defused when the head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, announced he would do “whatever it takes” to stop this break up happening, unveiling an emergency programme of backstop bond buying by the central bank. This reassured private investor that they would, at least, get their money back and bond yields in countries like Italy and Spain fell back to earth, ending the risk of a destructive debt spiral.

But the latest deadlock in Rome is nevertheless the biggest crisis in the eurozone since Greece last threatened to leave in 2015. And Italy is a much larger economy than Greece. If the third largest country in the bloc exited the euro, it is doubtful the single currency would survive.

Falling bank shares dragged down Europe’s main share markets. At the close the UK’s FTSE 100 fell almost 1.3%, while Germany’s Dax was down 1.5% and France’s Cac 1.3% lower. “It’s a market that is totally in panic”, said a fund manager at Anthilia Capital Partners, who noted “a total lack of confidence in the outlook for Italian public finances”. And the chief economic adviser at Allianz in the US said: “If the political situation in Italy worsens, the longer-term spill overs would be felt in the US via a stronger dollar and lower European growth.”

So whether you look locally or globally its risk on at the moment, and we are it seems to me teetering on the edge of our Scenario 4. This will not be pretty and it will not be quick. I see that slow moving train wreck still grinding down the tracks, with no way out.