There is an interesting paper the Reserve Bank NZ has put out, seeking comments by 31 August. The Future of Cash Use. It was issued in June 2019.

The paper describes the transition to digital alternatives, and explains some of the reasons. But what caught my eye was this section. “All members of society will lose the freedom and autonomy that cash provides, be more exposed to cyber threats, and lose the ability to use cash as a back-up form of payment”. And “other activity in the shadow economy is unlikely to be affected by the disappearance of cash as people find other ways to circumvent the law”.

So two points, New Zealand followers you might want to read the paper, and make a submission – not been much publicity so far.

Those following the DFA campaign relating to the War on Cash in Australia, here is more evidence that the proposal to ban cash transactions above $10,000 will not achieve their stated aims – but of course there is a wider monetary policy objective, as we have discussed.

6 Considerations arising from having less cash in society

Given the trends in cash demand and the cost pressures on the commercial supply of cash in New Zealand, it is possible that cash will become less widely available or used in the medium to long term. The effects of less cash in society would be felt more keenly by certain groups of people who rely on cash and for whom no practicable substitute exists. The severity of these impacts would be worsened if the transition to a society with less cash acceptance occured before mitigating measures could be put in place. Further, the size of the affected groups might not be large enough to motivate cash providers to ensure future cash availability, but the size might also not be negligible.

This section summarises the information in table 1 and Appendix A and the issues that should be considered if cash use and availability decline.

Issue 1: People who are financially or digitally excluded could be severely negatively affected.

Cash provides access to the financial system for those who face barriers to financial inclusion. Further, in a society with less cash, barriers to digital inclusion could become barriers to financial inclusion.

- Barriers to financial inclusion include limited access to the

banking system due to either a lack of trust in online security, skill

or motivation to use online financial platforms, or banking

restrictions. People who are not banked or have limitations to accessing

the banking system tend to be people without identification and proof

of address, people with convictions, people with poor credit histories,

people with disabilities, illegal immigrants and children.Elderly people

typically rely more than others on cash as a form of payment.

This could be due to low trust in online payments, low ability or low motivation to learn new payment techniques. People with physical disabilities, such as sight or intellectual impairments, might also find cash a useful form of money. Children are also subject to financial exclusion as banks do not issue debit cards to children under the age of 13. Further, New Zealand banks have full discretion in the customers they service. This means that some people who do not meet certain bank policies cannot obtain or keep accounts with those banks. Appendix A describes additional groups that rely on cash rather than digital money. - Barriers to digital inclusion include insufficient internet coverage, affordability constraints for technology hardware or data plans, lack of skills, lack of confidence and low motivation to use digital platforms. For example, even if people have access to the internet they might not be motivated to upload personal details to an online bank account due to privacy concerns.

Issue 2: Tourists, people in some Pacific islands and people who use cash for cultural customs might be negatively affected if they cannot use substitutes.

Tourists

Currently most tourists use cash as a reliable and easy-to-use form of payment. Reserve Bank research has revealed that cash is typically issued to Auckland and overseas and sent back to the Reserve Bank from the South Island. This movement is likely due to the movement of tourists. Many retailers in New Zealand do not accept credit cards (or contactless payments) due to their higher interchange fees, preferring instead to accept debit and EFTPOS cards (which require a New Zealand bank account) that incur much lower costs for the retailers.We are not aware of the extent to which inbound tourists’ own financial services’ fees or portability, or their prior understanding of transacting in New Zealand, influence this behaviour.

As per Appendix A, tourist access to payments in New Zealand could be met by overseas-issued debit cards if cash were not available. Further, competition might cause some retailers to accept tourist credit cards despite higher interchange fees if cash was not available. Bounie et al (2015) show that higher competitive pressures (the threat of losing sales) increase the probability that a retailer will accept credit card payments despite the higher costs.

Even if electronic payment alternatives were reliable, tourists might be disadvantaged due to language and cultural barriers that create actual and perceived barriers to payments in New Zealand. Further, tourists might be particularly vulnerable to risks of robbery or loss of payment cards if they could not rely on cash as a back-up payment.

Pacific Islands

Niue, the Cook Islands and Tokelau rely on New Zealand banknotes and coins for their physical currency. The size of these island economies has been thought to be a contributing factor to their use of New Zealand currency. In addition, these islands are formally defined as states in free association within the Realm of New Zealand. New Zealand banknotes are also used in the Pitcairn Islands.

The Reserve Bank does not have a formal arrangement to supply these economies with banknotes and coins. The supply of banknotes and coins to these islands is facilitated by commercial providers, tourists, and transfers from families. There are no ATMs on Niue and Tokelau. The Cook Islands has two ATM providers and also issues its own banknotes and coins. These islands also have access to digital money as in New Zealand.

Cultural customs

New Zealand’s banknotes have been referred to as the country’s business card. The designs on the notes represent many of our cultural icons and contribute to our national cultural identity. Cash is also used in many cultural customs in New Zealand. Some cultures that use cash as gifts in traditional ceremonies might find that part of their cultural identity is lost if they can no longer access cash easily. For instance:

- A Chinese custom is to give cash to junior family members and friends during celebrations including New Year (Hoong Bouw — giving money in red envelopes), at funerals, and during tea ceremonies in traditional Chinese culture.

- Some cultures have a wedding money dance where cash is gifted to the bride and groom as they dance (the Philippines’ Saya ng Pera, and the Taualuga in Samoa, Tonga and Western Polynesia).

- Western cultures give coins to children who lose their baby teeth (Tooth Fairy).

Issue 3: All members of society will lose the freedom and autonomy that cash provides, be more exposed to cyber threats, and lose the ability to use cash as a back-up form of payment.

If cash use and availibility were to decline, an issue for all members of society could be the loss of freedom that cash provides in terms of autonomous spending and wealth stores, privacy, ability to live off the grid, and ability to avoid the banking system. This could result in a significant loss of social freedom in aggregate and increased cyber security risks (leading to an increase in national security risks). Lastly, society would lose the benefit of cash as a ‘back-up’ form of payment, although the usefulness of cash in this role is limited.

Reduced freedom

Cash is anonymous, so provides consumers with autonomy or discretion in how they choose to spend their money or store their wealth. The feature of full anonymity creates personal and societal freedom and has not been replicated in digital currencies. There are three elements in this freedom; the first relates to the desire for privacy in making transactions, the second relates to the desire to avoid banks or government regulation, and the third relates to exposure to cyber-crime.

First, cash payments and balances cannot easily be traced. Central agents and third parties (such as banks and governments) cannot easily intervene or stop cash payments outside the banking system. This is a unique feature of cash and is not fully replicated by any other form of money. This anonymity gives people full control of and discretion with their finances. Independent bank accounts could provide personal freedoms but they are not always available or sufficient. For example, individuals who are in abusive and controlling circumstances might benefit from cash as it is easier to obtain and hide when other personal freedoms are restricted.35 Additionally, people might feel that they benefit from the choice of using an anonymous form of payment if it were ever needed.

However, the difficulty in tracing cash makes it relatively more vulnerable to theft, accidental losses and fraudulent payments (inadvertently accepting counterfeit notes). For this reason, some argue that people would be better off with a partially anonymous form of payment, where only the minimum information is given regarding the identity of the payer and payee in each transaction, but each transaction is recorded. These payments include, for example, vouchers, and prepaid gift (debit or scheme) cards.36

Second, the offline and anonymous features of cash enable people to separate their transactions and stores of wealth from the banking system and some government interventions. There are legitimate motivations for this separation.

- There is currently no guarantee of the safety of bank deposits in New Zealand.37 Banks take household and business deposits and lend them to borrowers — there is a risk that borrowers might not be able to service their debts. Households and businesses could lose their deposits if banks were engaging in overly-risky lending or if a severe series of events occurred and many loans were not repaid.

- People might also want to remove their savings from the banking system if the Reserve Bank charged negative interest rates to stimulate the economy. Cash provides an avenue for people to avoid this form of government intervention or any other government intervention that might occur in the future, such as capital controls.

- Relatedly, people might want to store wealth outside the banking system if they have low fundamental trust in banks or the government. Examples are individuals who have immigrated to New Zealand from countries where trust in the financial system is low, or where government appropriations of assets were not uncommon. If there were less cash in society, individuals would lose their privacy and autonomy from government in the sense that all their transactions and savings would be fully traceable if permitted by law.

Third, storing and transacting in cash reduces exposure to cybercrime, such as financial losses and identity fraud. On a societal level, New Zealand might be more exposed to cybercrime such as state-funded cyber threats if it were totally reliant on the banking system and digital money for all transactions and savings. On a personal level, some people might prefer to keep their identities and finances offline due to cyber concerns.

The loss of freedom in society in the above three areas could result in demand for a form of digital currency issued by the central bank that replicates some of the autonomy of cash. There are other assets in which people could store their wealth that are offline and removed from the financial system, for example, commodity assets and property. However, these are more difficult to transform into spendable money and can come with a different set of risks including fluctuating values.

Therefore, people might demand a central bank digital currency that provides lower traceability than current electronic payments and accounts and presents an alternative to the banking system. This could be in the form of accounts with the central bank or tokens issued by the central bank, which carry a very low risk of default and sit outside the commercial banking system. A central bank digital currency could also be designed to provide a low cost form of payment to put downward pressure on uncompetitive prices in the payment system. Alternatively, consumers might ask for deposit protection and greater regulation of the banking system.38

People might also value the freedom and autonomy of cash for illegitimate reasons. As noted in section 2, cash is used in the shadow economy to facilitate illegal transactions or as a means to hide income and reduce tax and other obligations. The International Monetary Fund estimated New Zealand’s shadow economy at 11.7 percent of GDP in 1991 -2015. 39 It is difficult to assert what might occur in the shadow economy if we had less cash. At the margin, some shadow economy activities could be reduced as people consider the additional difficulty of engaging in them without anonymous payments. For example, some people might be dissuaded from buying illegal goods and services if they could not avoid leaving electronic records of their purchases. However, it is also possible that criminal activity would innovate to other mechanisms or forms of payment discussed below.

There is debate on whether the anonymity of cash enables crime or whether illegal transactions would continue without cash. Rogoff (2016) and McAndrews (2017) agree that, without cash, criminals could use commodity money (i.e. gold), foreign currency, and inflated invoices. But they disagree on the extent to which these substitutes would be used. Rogoff (2016) argues that there is no complete substitute for cash, so criminal activity would be hindered if there were less cash in society. McAndrews (2017) argues that inflated invoices would become the most likely medium of exchange for criminals. He suggests that a society without cash would likely move towards deeper institutional corruption of businesses as criminals launder money obtained from illegal transactions. He also warns that innocent businesses could find themselves forced into money laundering as criminals look for businesses to issue inflated invoices.

Issue 4 considers how some tax evasion might be reduced by less cash.

Loss of emergency back up

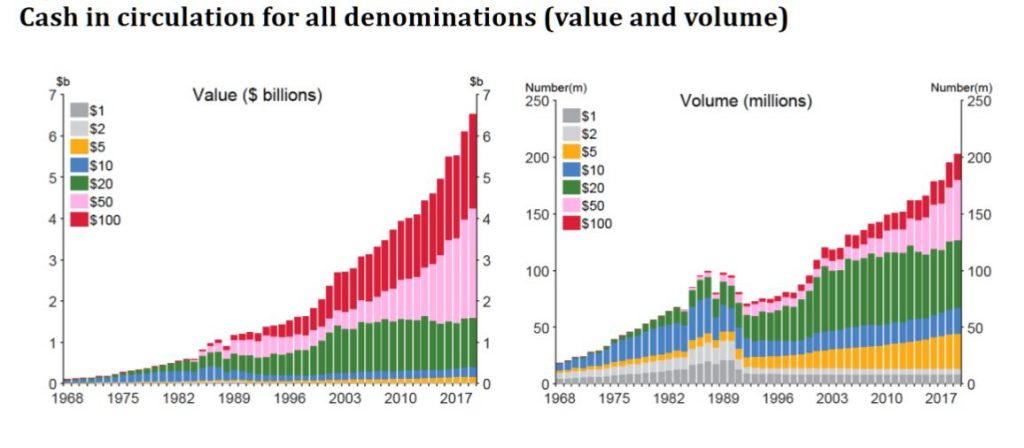

Cash can be a back-up payment mechanism when electronic payment systems are not in operation or otherwise unavailable. The Reserve Bank survey on cash use indicated that 37 percent of people held cash just in case it was needed (i.e. not for immediate transactions). Cash is particularly useful in case of ‘personal emergencies’, or localised or short disruptions in electronic payments systems, and after large-scale events conditional on the availability of retail stores able to accept it. Figure 2 shows a spike in CIC as a percent of GDP in 1999 that could be attributed to the ‘Y2K’ uncertainty.

Cash has several limitations in its usefulness as a back-up payment in case of large-scale events or natural disasters. Because the supply of cash and most retail operations are reliant on electricity and communications, IOUs between small groups or people who are known to each other might be more effective in periods of long electricity outages such as those that occur in natural disasters. There might also not be sufficient cash infrastructure capacity to meet a national transition to cash in an emergency.

In addition, the National Risk Unit does not recommend including cash in a civil defence kit or give guidance on the best means of payment in a national disaster response period. This could be because people already have their essentials in their civil defence kits, retail stores might not be operating, and emergency responders will provide additional supplies. In the weeks following the Christchurch February 2011 earthquake, public demand for cash did not increase substantially. Commercial banks anticipated an increase in demand for cash and increased their stores of cash and set up temporary ATMs based on generators. However, the bulk of these cash stores returned to the Reserve Bank relatively quickly. Figure 2 shows CIC did not peak as a share of the population during 2011.

Issue 4: On balance, there would be limited effects on budgeting, financial stability and government revenue.

Transitioning to a society with less cash does not significantly or negatively affect household budgeting, financial stability and government revenue.

Budgeting

Cash is widely cited as a budgeting tool. Psychological studies show that paying in cash incites a higher psychological pain of parting with funds. This is because the tangible nature of cash results in high transparency of payments and so generates a greater awareness of spending.40 This greater ‘pain of paying’ encourages less spending and is useful for managing discretionary spending, but it could reduce willingness to pay bills or debt. Shah et al. (2016) suggest that consumers should automate their essential payments and savings using online banking then spend disposable (leftover) income using cash. Cash might also be useful for limiting spending when people need to keep money separate for other purposes.

People who prefer to use cash for budgeting might benefit from new electronic budgeting tools such as budgeting applications on mobile phones. For example, several banks in Dubai provide real time balance updates or notifications every time money is spent, replicating the relatively high ‘pain of paying’ that cash provides.

Cash is not the only nor the most important budgeting tool available for people with low or no disposable incomes, high debts, overspending habits, or poor mental health. For these groups, commonly cited budgeting tools include awareness and education, direct credits, multiple bank accounts, and removing overdrafts and credit. Cash is used for people who are in full financial management in a Total Money Management programme as they are allocated their weekly spending in cash.41

However, the anonymity of cash makes it difficult for budgeting advisors to identify areas of overspending. Cash also enables people to default on automatic payments (for bills or debts) as they can withdraw their full bank account balances into cash. Further, withdrawing money into cash puts people at a higher risk of robberies than if they did not withdraw their money. For example, people who withdraw their income payments from ATMs at night to avoid automatic payments (processed in the morning) face a risk of robbery, particularly if these habits are well known in the community.

Financial stability

A society with less cash does not pose a risk to financial stability. Cash represents a claim on the government and carries low default risk. In theory, the ability of depositors to convert their savings into cash represents a form of market discipline on banks that encourages them to operate prudently. However, there is little empirical evidence to support this. Engert et al. (2018) evaluate the bank runs during the 2007 – 2008 Global Financial Crisis and determine that cash withdrawals are a small and unimportant source of market discipline on banks. Shin (2009) finds that the Northern Rock bank run was triggered predominantly by wholesale runs, and the in-branch runs to cash were insignificant.

Market discipline is only one form of discipline safeguarding our financial system. Another form is regulatory discipline. The Reserve Bank is mandated to use prudential regulation and supervision to contribute to a stable financial system. The third form is self-discipline, whereby financial market institutions self-regulate to ensure their ongoing prudent operation.

The second aspect of stability is payment stability. Migrating from two payment systems to one payment system would consolidate operational risk in the single payment system. Greater emphasis would be required on ensuring the operational reliability of the single payment system if people could not easily revert to cash if there were a system outage. Most electronic payments (except cryptocurrencies) rely on the same back-end payment systems which, exhibit several single points of failure.42

Increased tax revenue and reduced seignorage

Government revenue could be affected in two ways if cash use and availability declined. First, removing the availability of notes and coins might increase tax revenue as businesses would no longer use cash to reduce their tax bills. The Inland Revenue Department has reported that the most common ‘hidden economy’ activity is the underreporting of taxable income, which includes income from cash jobs and transactions.43

Exactly how much tax revenue is lost due to this type of activity is unknown. A tax working group paper suggests that unincorporated self-employed individuals under-report approximately 20 percent of their gross income. This estimate is based on a study commissioned by Inland Revenue44 and could represent $850 million per annum in lost tax revenue from unincorporated (non-trust or non-corporation) taxpayers. There is considerable uncertainty as to the extent to which this number includes self-employed people who are evading tax by underreporting cash revenue versus other types of underreporting. It is also not certain that those reducing their tax burdens by underreporting cash revenue would increase their tax payments if cash were used less.45

Second, seignorage revenue might decline if the value of CIC declined significantly. Seignorage revenue is the profit the Reserve Bank makes from producing and selling cash and investing the profits, as well as any profit the Reserve Bank makes from financial market trading. 46 The Reserve Bank estimates that it made around $148 million in seignorage revenue last financial year by issuing cash and investing the profits.

Other activity in the shadow economy is unlikely to be affected by the disappearance of cash as people find other ways to circumvent the law, as described in Appendix A. People who can no longer launder cash will likely switch to other methods.