Home ownership among young people is declining, as mortgage debt almost doubles for the same age group, results from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey show. It also shows young people are living with their parents longer.

The Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research undertakes the survey every year. It’s Australia’s only nationally representative household longitudinal study, and has followed the same individuals and households since 2001.

The survey shows the rate of home ownership among 18 to 39 year olds declined from 36% in 2002 to 25% in 2014. In the same age group, the decline in home ownership has been largest for families with dependent children, falling from 56% to 39%.

Even for those in this group who manage to buy a home, mortgage debt has risen dramatically. In 2002, 89% of home owners in this age range had mortgage debt. By 2014 this had risen to 94%.

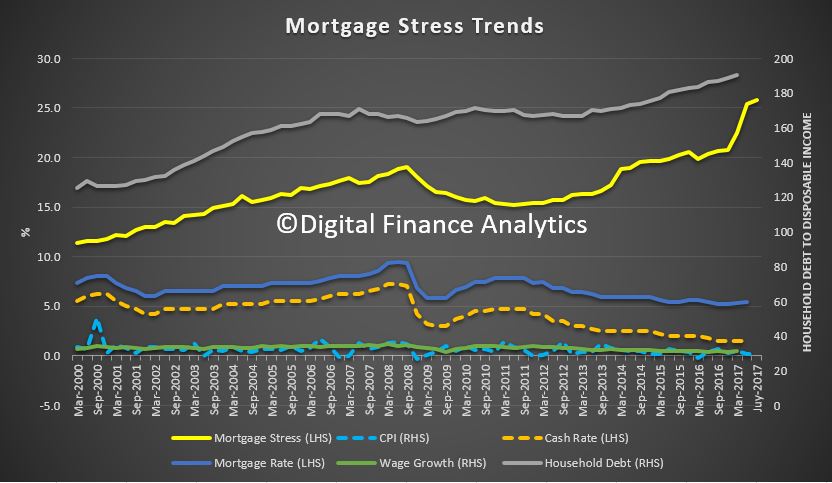

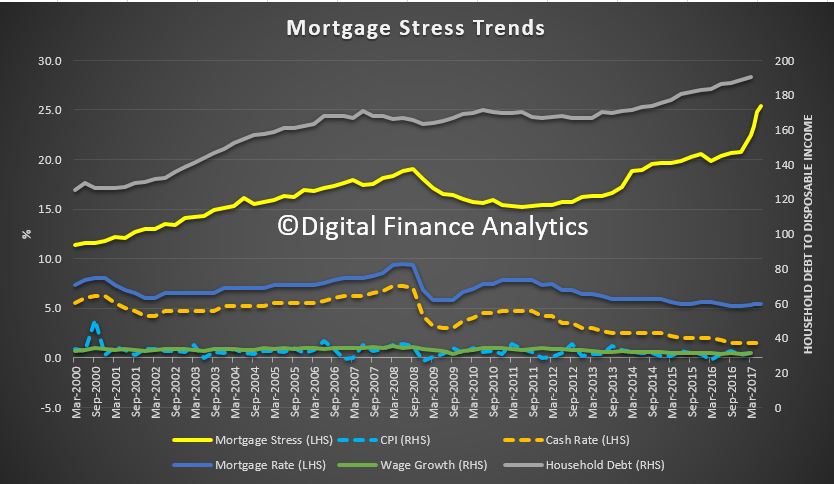

More significantly, the average home debt rose considerably. Expressed in December 2015 prices, average home debt grew from about A$169,000 in 2002 to about A$337,000 in 2014. Low interest rates since the global financial crisis have meant mortgage repayments for these home owners have remained manageable, but this group is very vulnerable to rate rises.

Detailed wealth data in the survey, collected every four years since 2002, show this increase in debt and decrease in ownership are part of a trend in the wider population. HILDA shows 65% of households were in owner-occupied dwellings in 2015, down from 69% in 2001.

In fact, the decline in home ownership has been greater than the decline in owner-occupied households. This is largely because adult children are living with their parents for longer.

For example, the HILDA data show that the proportion of women aged 22 to 25 living with their parents rose from 28% in 2001 to 48% in 2015. For men this proportion rose from 42% to 60%.

Among those who manage to access the housing market, the data shows that the growth in home debt is not simply because they are borrowing more to purchase their home. A surprisingly high proportion of young home owners (between 30% and 40%) actually increase their debt from one year to the next, despite most of them remaining in the same home. Even over a four-year period – for example, from 2010 to 2014 – at least 40% of young home owners with a mortgage increase their nominal home debt.

The proportion of people with home debt that exceeds the value of their home – that is, negative equity – has also risen. In 2002, 2.4% of people had negative equity in their home; in 2014, 3.9% had negative equity. This is a relatively small proportion, but this could change as even small decreases in house prices will result in substantial increases in the prevalence of negative equity.

How this changes with location, income and profession

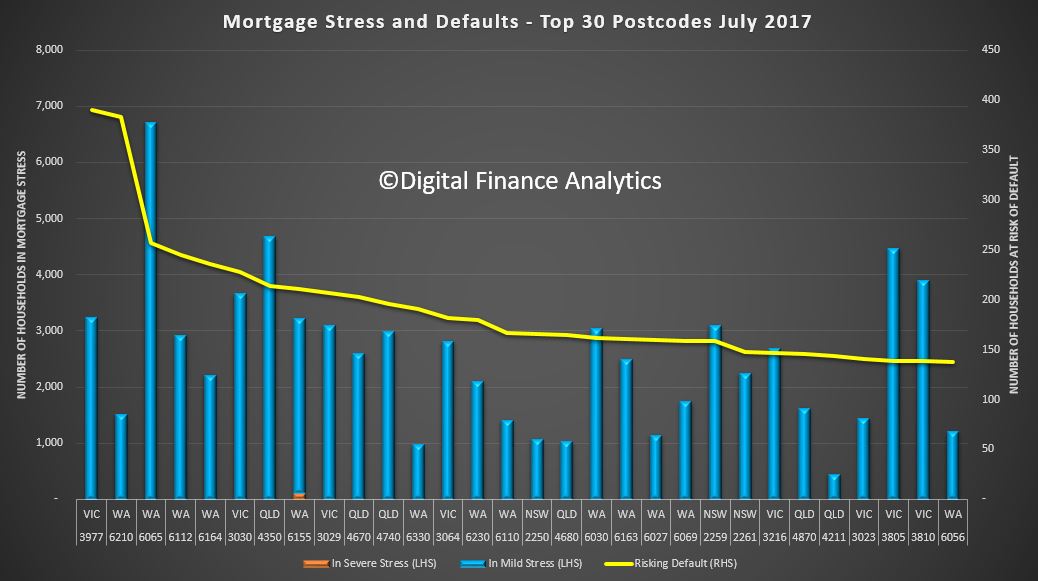

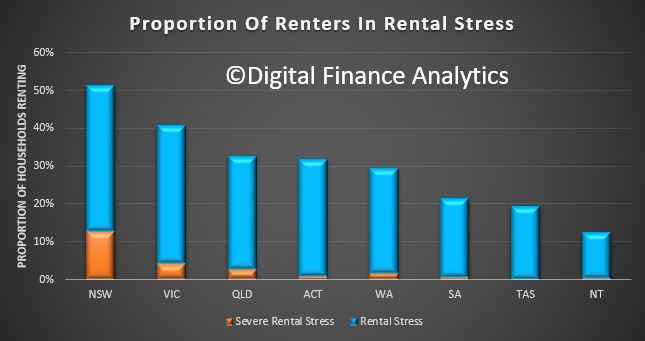

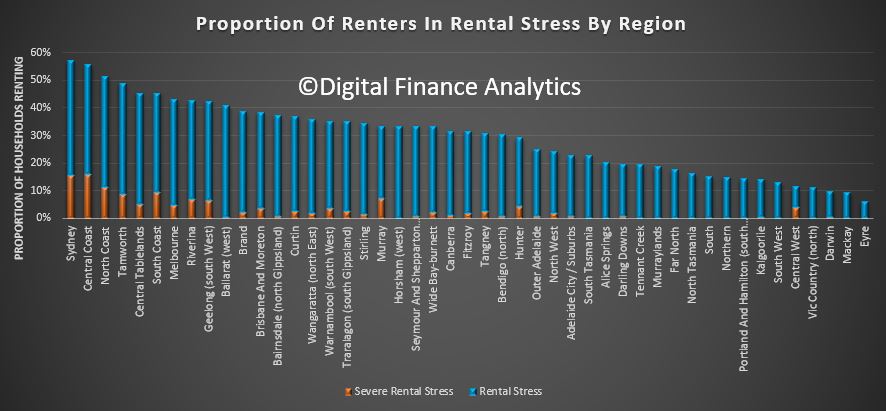

In 2014, less than 20% of Sydneysiders aged 18 to 39 were home owners, compared with 36% or more in the ACT, urban Northern Territory and non-urban regions of Australia. To a significant extent this reflects differences across regions in house prices.

Sydney and Melbourne have particularly high house prices, while non-urban areas generally have comparatively low house prices. Regional differences in the incomes of 18 to 39 year olds also play a role.

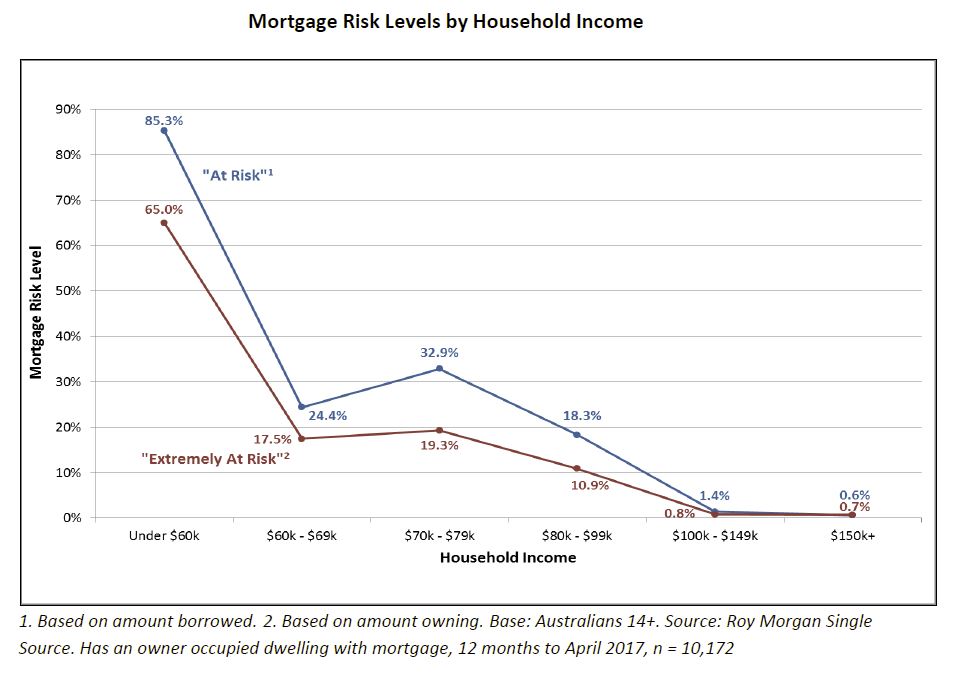

Those with the highest home-ownership rates are professionals and, to a lesser extent, managers. They experienced relatively little decline in home ownership.

For workers in other occupations, home ownership has declined substantially. In 2014 home ownership was especially rare among community and personal services workers, sales workers and labourers.

This decline represents profound social change among this age group, where renting is increasingly becoming the dominant form of housing. In 2002, 61% of people aged 35 to 39 were home owners – a clear majority of their age group. By 2014, this proportion had fallen to 48%.

The changing housing situation of young adults is part of a broader change in the distribution of wealth in Australia. The HILDA Survey shows that differences in average wealth by age have grown since 2002. For example, in 2002, median net wealth of those aged 65 and over was 2.8 times that of people aged 25 to 34. In 2014, this ratio had increased to 4.5.

The decline in home ownership among young adults and this broader trend in wealth have implications for their long-term economic wellbeing and indeed for the retirement income system. Even if house price growth moderates and many of those currently aged under 40 ultimately enter the housing market, it’s likely that a rising proportion will not have paid off the mortgage by the time they retire. It may be that many will resort to drawing on superannuation balances to repay home loans, in turn increasing demands on the Age Pension.

Professorial Research Fellow and Deputy Director (Research), HILDA Survey, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne