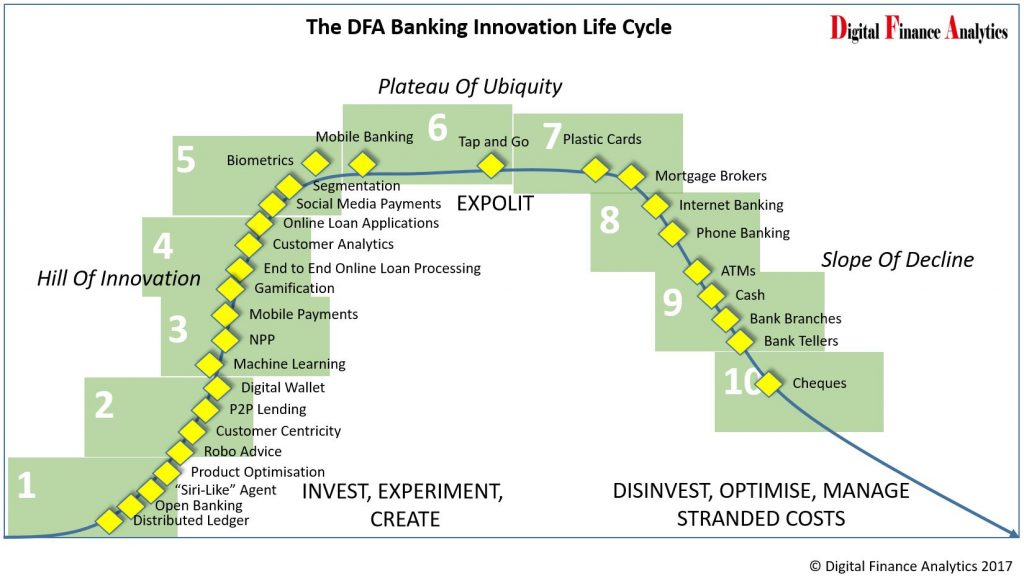

Given the tenor of the Royal Commission responsible lending inquiries this week, which focussed on the complexities of brokers and lenders complying with their responsible lending obligations, we believe the future will be distinctly digital. Our banking innovation life cycle road map calls this out.

To illustrate the point, there was a timely announcement from the Opica Group who have a new, and they claim Australia’s first responsible lending engine” (RELIE). This from The Adviser.

A new artificial intelligence-based expenses verification engine has been launched for brokers and lenders to ensure responsible lending and compliance obligations are met.

Billing the tech as “Australia’s first responsible lending engine” (RELIE), the Opica Group has launched the platform to help “protect any broker or lender from a breach of their responsible lending requirements”.

According to Opica Group founder Brett Spencer, the platform is needed because “lenders traditionally have been very quick to put blame on brokers for any application that goes sour”.

Mr Spencer said that following a tighter regulatory environment and “greater scrutiny being placed on our industry by regulators”, the group identified that “brokers needed something that provided them some protection”.

As such, it built the RELIE platform to enable brokers (and lenders) to perform a “RelieCheck” that could prove they had done the adequate checks into expenses and the consumer’s ability to service the loan.

How it works

The RELIE engine makes use of a specially built artificial intelligence engine, Sherlock™, which analyses a consumer’s banking and credit card transaction data over a period of 12 months and automatically provides “income verification, an understanding of the client’s mandatory expenditure, and therefore their ability to service a loan”.

According to the group, the key differentiator of the RELIE platform when compared to credit checks is that it uses machine learning to categorise transactions, allowing for the differentiation of transaction types, including mandatory versus discretionary expenditure and recurring versus one-off spending.

It also automatically highlights areas of concerns within the transaction data such as undisclosed debts, spikes in expenditure of high-risk categories such as gambling, and possible changes in life circumstances such childbirth.

Mr Spencer commented: “With the advancements in technology and legislation crackdown, we saw an opportunity to protect brokers and automate significant components of an applicant’s income and expense verification process…

“We believe that running a RelieCheck will protect any broker or lender from a breach of their responsible lending requirements.”

Speaking to The Adviser, Mr Spencer elaborated: “While a credit check simply looks at your credit worthiness, a RelieCheck looks at the consumer’s 365-day spending and income transactions and interrogates the data from a responsible lending perspective.

“It then presents back to the broker or lender a summary of exactly what, when and where an applicant’s income and expense are positioned.”

However, the Opica Group founder said that while the AI engine “does all the grunt work” to auto categorise and allocate spends to a range of buckets (such as mandatory versus discretionary expenses), the broker is able to review each category of spend and re-allocate expenses to a different category as part of their responsible lending discussions with the customers.

Each change made is then notated by the broker in order to meet their responsible lending requirements.

Revealing that the engine has been 16 months in the making, Mr Spencer said that the group wanted to “create a platform that a broker could use to protect themselves from any unintended breach of their responsible lending requirements”.

He added: “We also wanted to speed up the physically demanding process of paper-based statement reviews so that a broker could reduce the amount of time it takes to process a loan, and in the process providing a far greater service to the customer.”

Opica Group revealed that “early indications” have shown that by performing a RelieCheck on an applicant, a broker or lender could reduce processing times by approximately 90 minutes per application (when compared to manual assessment of the applicant’s banking and credit card transactions).

Mr Spencer concluded: “We want to create a new industry standard.

“Data is a commodity, but what you do with the data is the key ingredient.”

He added that he did not believe anyone else was thinking about “what we do with the data to aid the lending process”.

Opica Group is reportedly working with a number of aggregators and lenders to establish whether the engine could be integrated into their customer relationship management (CRM) systems. The service costs $15 (plus GST) per applicant for a broker account, or $10 (plus GST) per applicant for an aggregator or lender account.