Despite suggestions that young people are losing interest in the platform, its 1.5 billion users still puts Facebook at the centre of social media. The site was launched in 2004, and so those meeting Facebook’s minimum age requirement of 13 will, in 2017, be the first generation for whom Facebook has always existed.

We are now able to reflect on the long-term use of Facebook, which has enjoyed unrivalled longevity and growth. Those who joined in their early teens are now in their twenties and have “grown up” on Facebook, documenting their life through text, images, videos, and geo-location data such as “check-ins”. We spent two years interviewing these twenty-somethings to explore how they had documented their experiences of growing up on Facebook.

Their Facebook profiles have become effectively an archive of their lives. As our participants scrolled back through their Facebook timelines with us, they recounted the experiences they had posted to the site: exam results, new romantic relationships, breakups, losing a job, travel, and so on. Sometimes seemingly banal disclosures would remind them of more complex stories that were not immediately obvious. A photo of one participant sleeping on her father’s couch, for example, reminded her of a painful breakup with a partner. For another, the gaps in his timeline elicited stories about his gender transition that led him to switch to a new profile.

As our participants delved into their past many reflected on points in their lives where they were making critical decisions about their futures such as graduation, launching their careers and starting their own families. Some were in their final year of university study and were looking for a job. Today, Facebook profiles have become almost as important as a CV. And, much like the preparation and polishing of a CV, young people are cleaning up their Facebook profiles – prioritising stories about travelling or voluntary work and making the embarrassing details about nights out with friends private or erasing them altogether in an attempt to present a more professional, measured, mature identity.

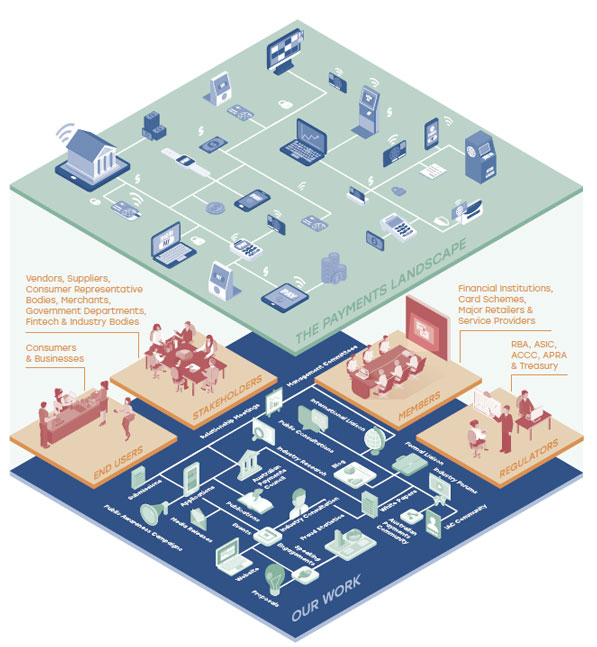

Job-seekers now perfecting Facebook timelines, not just CVs. Antonio Guillem/Shutterstock

Putting the best face forward

For many, Facebook has shifted from being the site on which to document carefree student days to a space where a more professional identity can play out. Recruiters have for some time examined social media profiles, something that raises important privacy questions. Facebook even now offers its own, work-focused Facebook app, Workplace, showing the company’s desire to expand into more areas of our lives.

Two participants in our study were final year medical students. Coached in a job-seeking seminar, they were told that the recruitment team would carry out web searches on the candidates, including Facebook pages. This was an incentive for them to tidy up their profiles, and reflect on how many years of Facebook posts might be interpreted by potential employers and patients.

The sociologist Anthony Giddens uses the expression “the reflexive project of the self” to explain how personal identity is not fixed in stone, but an ongoing project that we constantly work on. This concept is particularly applicable to social media such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter because it captures the way these services are embedded into young peoples’ lives, and their professional development.

By polishing their Facebook profiles they can revise their past – removing pictures or posts that no longer play a role in who they are, or who they wish to portray themselves to be. Entire events that once seemed significant can be removed, having since been diminished into the realm of teenage naivety as priorities, networks, and identities change.

Competing versions of identity

These erasures raise important questions. When in decades to come those who have grown up using Facebook are running for public office or moving into positions of power, how might we think differently about what constitutes a professional identity, and its relationship with our younger selves? Will future prime ministers be embarrassed by a love-struck selfie documenting a one month anniversary of their first relationship? Will future CEOs be deemed inappropriate for their jobs because of a flippant post made decades earlier? Should they?

Sports stars and politicians are often shamed and sometimes ruined for things they say on social media. Gymnast Louis Smith and footballer Joey Barton have found themselves in trouble for their questionable social media posts. Cheerleader Caitlin Davies’s career was ruined after a photo of her drawing offensive graffiti on an unconscious man was shared on Facebook.

The issue is that the hundreds or thousands of posts that make up twenty-somethings’ social media profiles are disclosures written and shared in the past, often forgotten and buried – until uncovered by someone scrolling back through them. In another case, the UK’s first youth crime commissioner Paris Brown resigned following the uncovering of apparently racist and homophobic comments posted on Twitter as a younger teenager.

Might this kind of scrutiny intensify as entire lives recorded on social media are dredged up and put under the microscope? Or perhaps our attitudes will change, and they will be appreciated for what they are – moments in time, often from long ago.

For either the carefully edited approach to Facebook or the forgotten posts that come back to haunt their creators, it will be interesting to see the impact on future generations. What, for example, will a child think on scrolling through the Facebook timelines of parents who grew up using social media? Might the edited, polished version of their lives that they have put forward on Facebook stand in place of memory, and so eventually become the recorded story of their lives, however carefully curated and managed?

Senior Lecturer in Media Studies, Liverpool John Moores University; Lecturer in Sociology, University of Tasmania