Frank Uhlenbruch, Investment Strategist in the Australian Fixed Interest team, Janus Henderson provides his Australian economic analysis and market outlook.

Market review

Australian government bond yields initially followed offshore yields higher

on optimism that a trade deal was imminent. However, sluggish domestic economic

data and Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) commentary on unconventional monetary

policy saw government bond yields end the month lower. Improving sentiment

supported equity and credit markets. Overall, the Australian bond market, as

measured by the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index, rose by 0.82%, with

price appreciation from modestly lower yields boosting the income return.

Three and 10 year government bond yields rose to their highs of 0.88% and

1.30% following reports of a ‘Phase 1’ trade deal between the US and China and

stronger US services sector data. Yields then rallied as it appeared a trade

deal may be delayed and RBA commentary on unconventional monetary policy was

seen as dovish. Australian three and 10 year government bond yields ended the

month 16 basis points (bps) and 11bps lower at 0.65% and 1.03%.

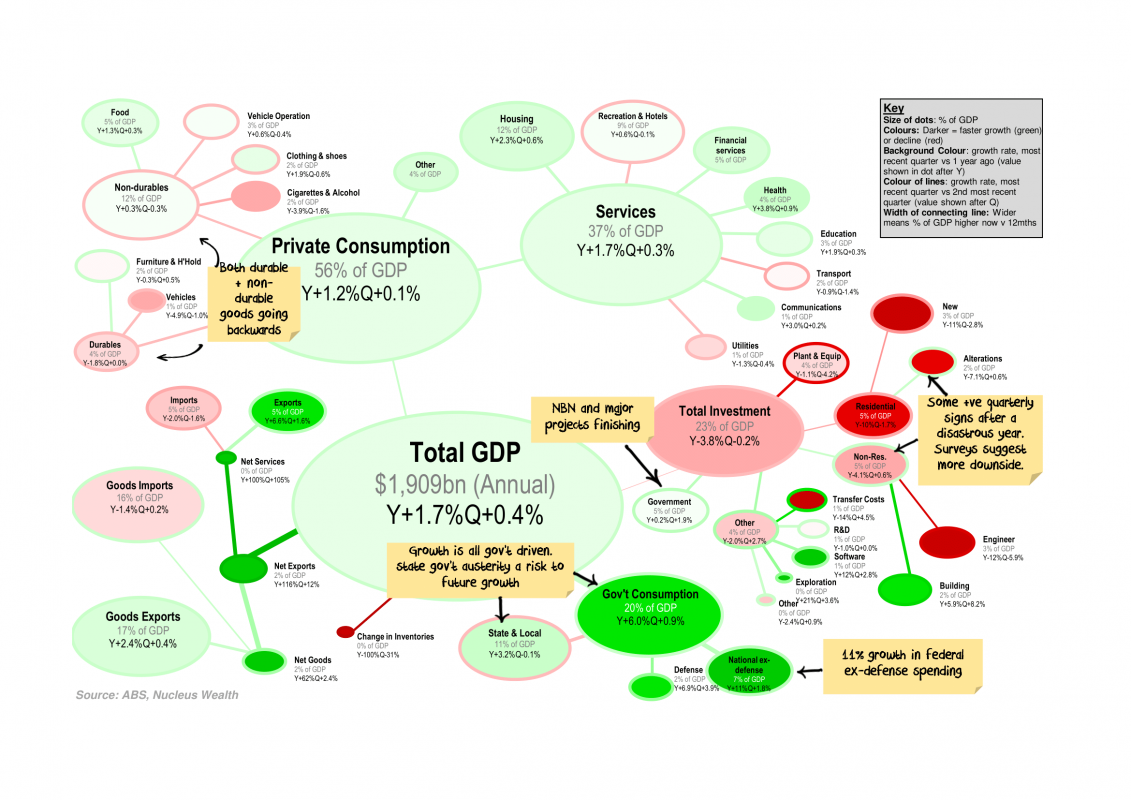

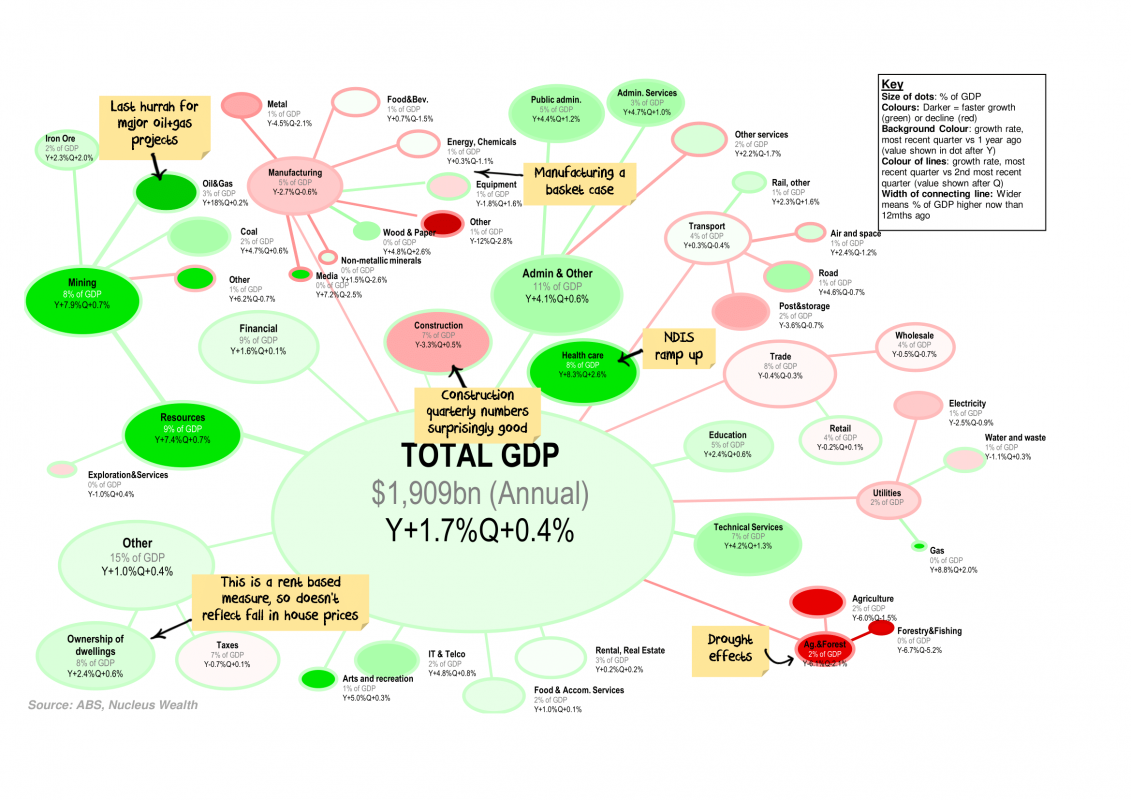

Australian data releases remained consistent with growth running at a

sub-trend rate, with limited signs of recent fiscal and monetary easing

boosting domestic demand. Retail sales for September were sluggish, gaining

0.2% over the month but falling by 0.1% in volumes terms over the quarter.

While there was an improvement in consumer sentiment in November, confidence

levels remain subdued with indications that uncertain consumers are saving

rather than spending recent gains from tax rebates and lower mortgage rates.

Despite a small improvement in business conditions in the October NAB

Business Survey, both confidence and activity measures remain below longer-run

measures and have yet to show signs of a meaningful response to earlier policy

stimulus. Consistent with sluggish survey readings, construction work done fell

0.4% in the September quarter, while private capital expenditure fell by 0.2%.

This data, along with weak retail sales, point to another quarter of subdued

growth in the upcoming release of the September quarter national accounts.

Labour market conditions softened, with employment falling by 19,000 in

October, the first fall in 16 months. The unemployment rate lifted from 5.2% to

5.3% and the participation rate fell from 66.1% to a still historically high

level of 66%. Wages growth remained modest, with the Wage Price Index lifting

by 0.5% over the September quarter for a yearly growth rate of 2.2%. RBA

commentary suggests that they expect to see wages growth around these levels

persist for some time before lifting as labour market slack is eventually

absorbed.

Against the backdrop of sluggish activity and perceived dovish central bank

commentary, markets moved to factor in further easing over 2020 after largely

ruling out a December move. Markets are assigning a 60% chance of a February

2020 easing and have a 0.50% cash rate fully priced by May 2020. By the end of

2020, markets are assigning a 40% chance of the cash rate falling to 0.25%, the

effective lower bound.

Credit markets benefitted from the improvement in trade-related risk

sentiment and investors’ ongoing search for yield, with the Australian iTraxx

Index rallying 3bps to end the month at 56bps. Primary markets were active as

companies looked to finalise debt funding ahead of the end of the year. Notable

deals included residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) issued by Bendigo

and Adelaide Bank, ING, and CBA, with the latter being the first RMBS deal to

replace the historically used Bank Bill Swap Rate (BBSW) with AONIA (Australian

Interbank Overnight Cash Rate) as a reference rate for the payment of coupons

to investors.

Market outlook

Our base case remains for an extended period of accommodative monetary

policy that will only be unwound once the RBA has confidence that inflation

will settle in the middle of its target band. The latest set of forecasts from

the RBA saw them downgrade their near-term economic growth forecasts by 0.25%,

although they left their 2020 and 2021 GDP forecasts unchanged at 2.75% and 3%.

With spare capacity being absorbed at a slower rate, the RBA pushed back the

timing of when core inflation reaches 2% from mid-2021, to the end of 2021.

While the RBA considered easing monetary policy at its November meeting, it

chose instead to join the US Federal Reserve and other central banks in pausing

to wait and see how policy easing to date flows through into the broader economy,

how trade developments unfold and the extent of any fiscal easing.

The RBA maintains an easing bias and is of the view that further cuts would

provide additional net stimulus. In a landmark speech, the RBA Governor

signalled that a 0.25% cash rate reflected the effective lower bound for the

cash rate. The Governor saw negative interest rates in Australia as

extraordinarily unlikely.

If further support for the economy was required when the cash rate was at

the lower bound, then the RBA would consider unconventional policy measures,

with the main focus on purchasing government bonds, including state government

bonds, from the secondary market to drive down the risk-free rate that affects

all asset prices and interest rates in the economy. If such policy support was

required, the Governor noted that a combination of policy responses, including

fiscal, would deliver the best results.

With little signs of recent policy stimulus and a turnaround in house prices

showing up in activity, labour market and confidence indicators, we look for a

further rate cut in February 2020 which would take the cash rate down to 0.50%.

The prospect of the Government bringing forward ‘Phase 2’ tax cuts worth around

$13.5bn in the May 2020 Budget, which would come into effect on 1 July 2020 ,

would significantly reduce the burden on monetary policy and rule out the need

for a further cash rate cut and unconventional measures. This is our central

case view and we see the stimulus from these measures raising the prospect of

the cash rate lifting over the latter part of 2022.

We see nearer term risks tilted towards our low case scenario, where the

cash rate falls to 0.25% and a lack of fiscal easing forces the RBA to

initially extend its forward guidance. A lack of a coordinated policy response

would see the RBA embark on a government debt purchase programme that flattens

the domestic yield curve. Overall, we see three and 10 year government bond

yields of 0.66% and 1.05% (at the time of writing) as offering little

opportunity to express strong views on duration.

We continue to remain attracted to maintaining a core exposure to

inflation-protected securities in an environment where policy is being firmly

directed to boosting growth and lifting inflation back towards central bank

targets. Despite a modest and ongoing lift in breakeven inflation rates from

the record low levels experienced in late August, current pricing suggests

markets still have little confidence that recent policy moves will gain much

traction. However, with the cost of buying inflation protection now so low, we

feel it makes sense to position for the prospect of a cyclical lift in

inflation over the next few years, especially if one contemplates even more

extreme policy measures to reflate economies.