The Reserve Bank of New Zealand is consulting on a new asset class treatment for mortgage loans to residential property investors within its capital adequacy requirements. They propose to separate investment and owner occupied loans from a capital perspective, (once loan types are defined), and apply different capital treatments, requiring more capital for investment loans, reflecting potential higher risk. This would be applied to both standards and advanced IRB banks, and they would allow a period of transition to the new arrangements, commencing 1 July 2015. The net impact would be to increase the capital costs to lenders of making investment mortgages, and potentially slowing momentum in this sector. RBA please note!

The Reserve Bank’s analysis shows that residential property investor loans are a sufficiently distinct category of loans and that by grouping them with other residential mortgage loans one is not in a position adequately to measure their risk as a separate group of loans. This can have negative consequences for a bank’s awareness of the proper risk associated with those loans and lead to insufficient levels of capital being allocated to them. The Reserve Bank therefore proposes that all locally incorporated banks hold residential property investment loans in a separate asset or sub-asset class. In addition, a primary purpose of the consultation is to seek views on how to best define a property investment loan.

Consultation closes on 7 April and once the Reserve Bank has settled upon a definition, it proposes to amend existing rules by requiring all locally incorporated banks to include residential property investment mortgage loans in a specific asset sub-class, and hold appropriate regulatory capital for those loans.

Reserve Bank Head of Prudential Supervision Toby Fiennes said: “International evidence suggests that default rates and loss rates experienced during sharp housing market downturns tend to be higher for residential property investment loans than for loans to owner occupiers.

“The proposal would bring the Reserve Bank’s framework more into line with the international Basel standards for bank capital. The proposed rule amendment is designed to ensure that banks hold adequate capital for the risks that they face from investment property lending.”

The Reserve Bank has previously consulted on a possible definition that would have seen loans to borrowers with five or more residential properties classified as loans to residential property investors. Partly as a result of submissions received, the Bank has reconsidered the definition, and is now consulting on three possible alternative ways to define loans to residential property investors:

- if the mortgaged property is not owner-occupied; or

- if servicing of the mortgage loan is primarily reliant on rental income; or

- if servicing of the mortgage loan is at all reliant on rental income.

The proposed new rule would apply to all locally incorporated banks.

While the current proposal is not a macro-prudential policy proposal, creating consistent asset class groupings to be used by all banks would help the Reserve Bank to implement targeted macro-prudential policies in the future, should that become necessary.

Looking at the proposals in more detail:

They propose that residential property lending should be grouped in a separate asset class because the risk profile of these loans is observably different from owner-occupier mortgage loans, particularly in a severe downturn. The capital requirements that apply to IRB banks require long run PDs to be estimated on the basis of data that includes a severe downturn or, where that is not possible, to include an appropriate degree of additional conservatism.

Fortunately in New Zealand, we have not had a severe housing downturn in recent decades. But this also means that we do not have information on the difference in terms to default rates between residential property investors and owner-occupiers in such a scenario.

Based on the information available from other countries that have had a severe housing downturn, there is evidence to suggest that property investor loans are more strongly correlated with systemic risk factors than owner-occupier loans. This would point to a higher correlation factor in the Basel capital equation than the one that is currently used for all residential property loans. Moreover, although minimum downturn LGDs are prescribed within BS2B, they are effectively calibrated to owner-occupiers. It is therefore likely that the estimated risk weights that banks currently use for residential investor loans are too low and do not adequately reflect the risk that these loans represent.

The higher risk associated with residential property investment loans does not only apply to IRB banks. A residential property investment loan made by a bank operating on the standardised approach is equally a higher risk loan compared to a loan to an owner-occupier. The Basel approach seems to deal with this by recommending higher average risk weights for all residential property loans under the standardised approach.

In New Zealand, this has been implemented by allocating risk weights to residential mortgage loans that range from 35 to 100 percent, depending on a loan’s LVR and the availability of lender’s mortgage insurance.5 However, housing loans are a crucial area for maintaining financial stability in New Zealand and these risk weights do not adequately capture the higher risk associated with residential property investment loans.

The Reserve Bank believes that in this area, there are good reasons why a consistent conceptual approach across standardised and IRB banks makes sense. In addition, the Reserve Bank has a suite of macro-prudential tools available to help address financial stability concerns in certain circumstances. Having the same asset class groupings across all banks would help the Reserve Bank to implement targeted macro-prudential policies if that becomes necessary. Contrary to previous consultation papers on this subject therefore, the Reserve Bank now proposes to include a new asset class for residential property investors within the standardised approach, i.e. BS2A. This new asset class would also have separate, prescribed, risk weights from those that apply to non-residential property investment loans.

It is necessary to define what constitutes an investment loan. The first and in some ways simplest option would be to restrict the current retail residential mortgage asset class to owner-occupiers only. Any mortgage on a residential property that is not owner-occupied would be classified as a residential property investment loan and grouped in a new asset class.

Banks would have to verify the use of a property under this option. This information is already being collected at loan origination to some degree. Possible ways of identifying whether a property is owner-occupied or not include checking the borrower’s residential address and

whether the property generates any rental income. Other possible indicators could include eligibility for tax deductibility of the mortgage servicing costs on the property. The Reserve Bank appreciates that there could be cases where a borrower has more than one owner-occupied residential property and splits his or her time between those addresses. An example could be if a borrower uses one address during the week for work purposes and another on the weekends when he or she is with the family. Another case might be a bach that is not permanently occupied but also does not generate any rental income. The information the Reserve Bank collects from banks on new commitments already distinguishes between owner-occupiers and residential property investors while allowing for owner-occupiers to occupy more than one residential address. The same or a very similar definition could be used to distinguish between second and more properties that are still owner-occupied and properties that are used as residential properties, subject to considering adequate safeguards to ensure that this is not used as an avoidance mechanism.

The Reserve Bank also appreciates that there could be challenges for banks to monitor how a property is being used. A second flat that is used as a second residence by the owner-occupier when the loan is taken out could at some point be let out. While the Reserve Bank does not expect banks to regularly seek confirmation form borrowers as to the use of a property, it is expected that reasonable steps are taken to maintain up to date information. This could mean updating important information when there is a credit event.

An alternative option would be to use mortgage servicing costs as an indicator. If mortgage servicing are predominantly reliant on the rental income the property generates, then that loan should be classified as a residential property investment loan. Predominantly was defined as more than fifty percent. In other words, if a borrower’s other sources of income minus the bank’s usual allowances for living expenses, other loan servicing obligations and so on are sufficient to cover more than fifty percent of the loan servicing obligation of the residential property, that is interest as well as repayment of principal, then the loan continues to be classified as a residential mortgage loan in the retail asset class. This test would only apply to investment properties. Owner-occupied properties would be exempt from this requirement and continue to be classified as residential mortgage loans. There is, however, a question as to the point at which the reliance on the property’s rental income separates that loan from loans to owner-occupiers. The Reserve Bank has previously consulted on a threshold of 50 percent. But this still leaves plenty of scope for borrowers to acquire a small portfolio of investment properties without those mortgages being classified as residential property investment loans. A stricter definition would be to make it dependent on any rental income.

Irrespective of which definition and asset class treatment is decided on, banks are likely to require some time to implement the new requirements. For example, banks will have to assess which of their existing exposures are caught by the residential property investment loan definition, make changes to their information capture and IT systems and retrain staff. This will take some time. The Reserve Bank is therefore currently minded to phase the new requirement in over a period of nine months.

IRB banks may also have to develop new models for their residential property investment loan portfolio, although that is not necessarily the case and existing PD models would form a good basis on which to build residential property investor specific models. IRB banks, however, would have to amend their capital engines for residential investor loans to use the proposed LGDs and correlation factors.

It is proposed that IRB banks operate under the same risk weight requirements as standardised banks until their new models have been approved by the Reserve Bank. Furthermore, it is proposed that the new asset classification for residential property investors takes effect from 01 July 2015.

They are also proposing changes to capital requirements for reverse mortgages. Managing a portfolio of reverse mortgages requires long term assumptions to be made concerning a number of factors. If those assumptions turn out to be wrong, the risk to a lender could be significantly affected. For example, advances in geriatric healthcare might mean that people stay longer in their houses than currently anticipated. That could increase the risk of incurring a loss on a portfolio of reverse mortgages due to compound interest, the possibility of the borrower being granted further top ups and the difficulty of predicted house prices years and decades ahead.

While arrangements whereby the reverse mortgage has to be repaid after a certain period of time or stay below a set LVR are theoretically possible, they are not the norm and would most likely be to the disadvantage of the borrower, and thus undermine the attractiveness of a reverse mortgage.

To emphasise, one way in which the risk profile of a reverse mortgages differs from a normal mortgage is in the time dimension. Whereas a normal mortgage loan decreases over time, the opposite is the case for a reverse mortgage.

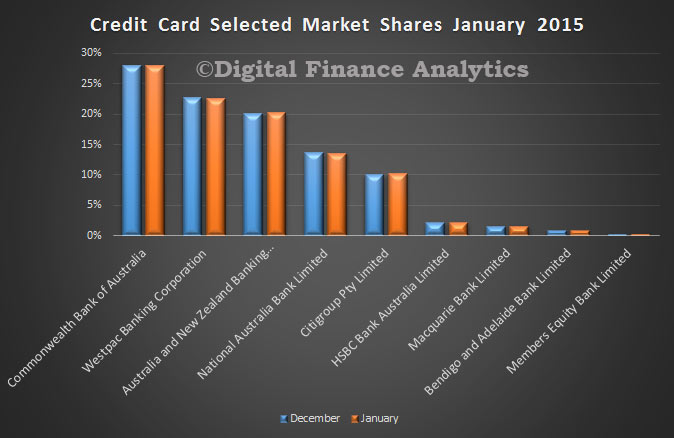

Finally, the Reserve Bank considers it more appropriate group credit card and revolving retail loans in the “other retail category and to remove QRRE as an option from its capital requirements for IRB banks. This would improve clarity within BS2B while having no direct impact on banks since no bank has been given approval to use the QRRE option.

Basel II framework for IRB banks introduced the concept of a ‘Qualifying Revolving Retail Exposure’ as one of three categories of retail loans. The other two categories are residential mortgages and other retail, a catch all for retail loans other than residential mortgages. The QRRE category is intended to be used for short-term unsecured revolving lines of credit, e.g. credit cards and certain overdraft facilities. In New Zealand credit card loans account for approximately 1 to 3 percent of banks’ total lending portfolios. Compared to the other two categories, the capital requirement for QRRE loans is generally lower (except for some very high probability of default (PD) buckets).

In line with Basel II, the Reserve Bank’s capital adequacy requirements provide for the use of the QRRE category. However, use of the QRRE classification is subject to Reserve Bank approval and no bank has been granted approval as yet. The Reserve Bank is concerned that some of the underlying assumptions of the QRRE category do not apply in the New Zealand context. The evidence supplied by banks when seeking approval for QRRE use has not able to demonstrate the validity of those assumptions in New Zealand.