The ABS published their finance statistics today to November 2014. It appears to me we have an unbalanced economy, where more and more lending is flowing into property, stoked by investment demand (and encouraged by negative nearing). As a results, house prices rise, inflating the bank’s balance sheets, and personal assets. But there is less lending for productive commercial purposes.

- The total value of owner occupied housing commitments excluding alterations and additions rose 0.5% in trend terms, and the seasonally adjusted series fell 0.2%.

- The trend series for the value of total personal finance commitments rose 0.2%. Fixed lending commitments rose 0.5%, while revolving credit commitments fell 0.2%. The seasonally adjusted series for the value of total personal finance commitments fell 2.2%. Revolving credit commitments fell 3.1% and fixed lending commitments fell 1.4%.

- The trend series for the value of total commercial finance commitments fell 2.8%. Revolving credit commitments fell 7.7% and fixed lending commitments fell 1.2%. The seasonally adjusted series for the value of total commercial finance commitments fell 2.6%. Fixed lending commitments fell 4.6%, while revolving credit commitments rose 3.8%.

- The trend series for the value of total lease finance commitments fell 2.3% in November 2014 and the seasonally adjusted series fell 4.4%, following a fall of 4.6% in October 2014.

|

Oct 2014

|

Nov 2014

|

Oct 2014 to Nov 2014

|

||

|

$m

|

$m

|

% change

|

||

|

|

||||

| TREND ESTIMATES | ||||

| Housing finance for owner occupation(a) |

17 169

|

17 248

|

0.5

|

|

| Personal finance |

8 729

|

8 746

|

0.2

|

|

| Commercial finance |

39 471

|

38 357

|

-2.8

|

|

| Lease finance |

428

|

418

|

-2.3

|

|

| SEASONALLY ADJUSTED ESTIMATES | ||||

| Housing finance for owner occupation(a) |

17 309

|

17 282

|

-0.2

|

|

| Personal finance |

8 922

|

8 730

|

-2.2

|

|

| Commercial finance |

39 011

|

37 992

|

-2.6

|

|

| Lease finance |

421

|

402

|

-4.4

|

|

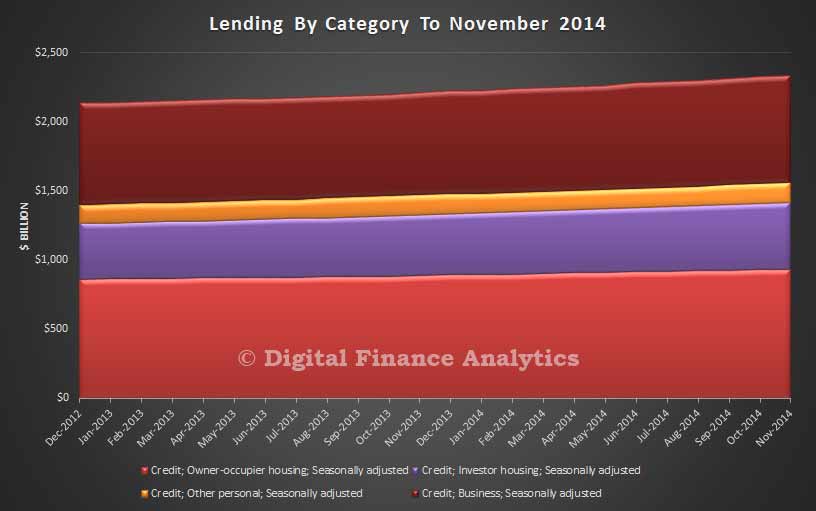

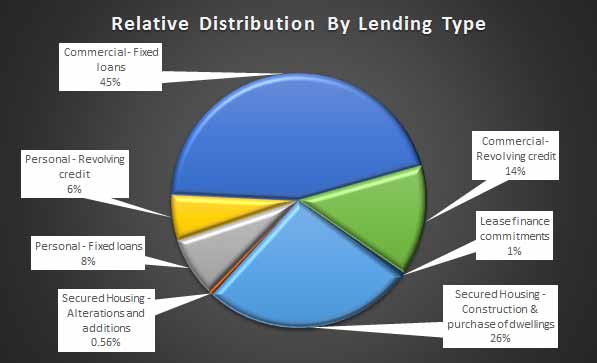

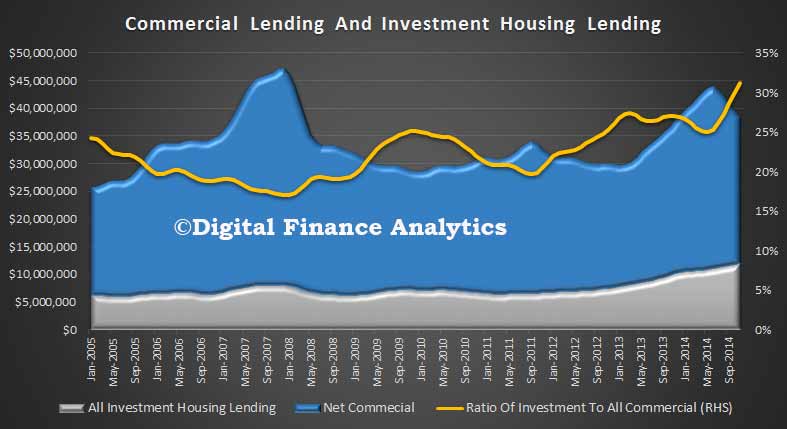

Looking at the data in more detail, we see that commercial lending represent 59% of lending.

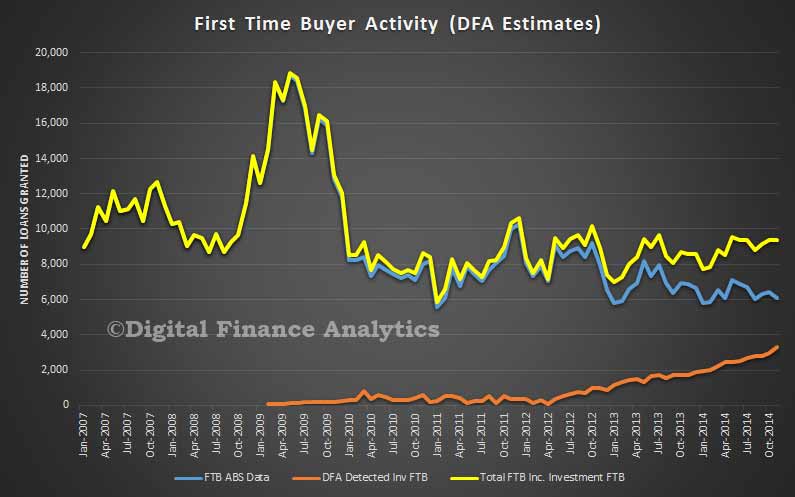

However, within commercial lending, we have lending for investment property. Cross matching the data. we see that of all commercial lending, more than 30% directly relates to residential investment property. Lending for other purposes has dropped.

However, within commercial lending, we have lending for investment property. Cross matching the data. we see that of all commercial lending, more than 30% directly relates to residential investment property. Lending for other purposes has dropped.

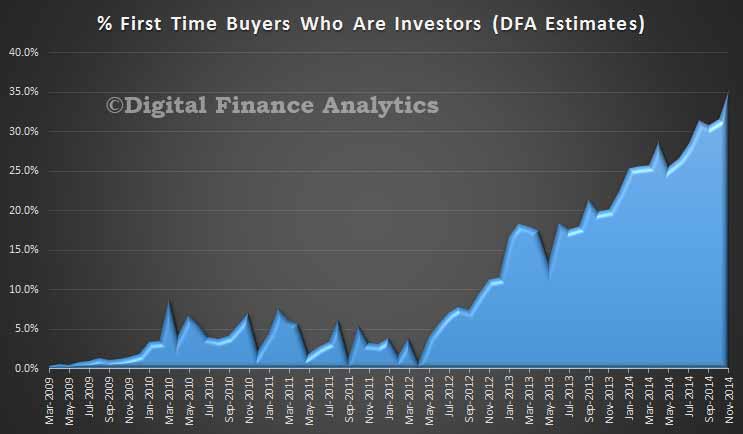

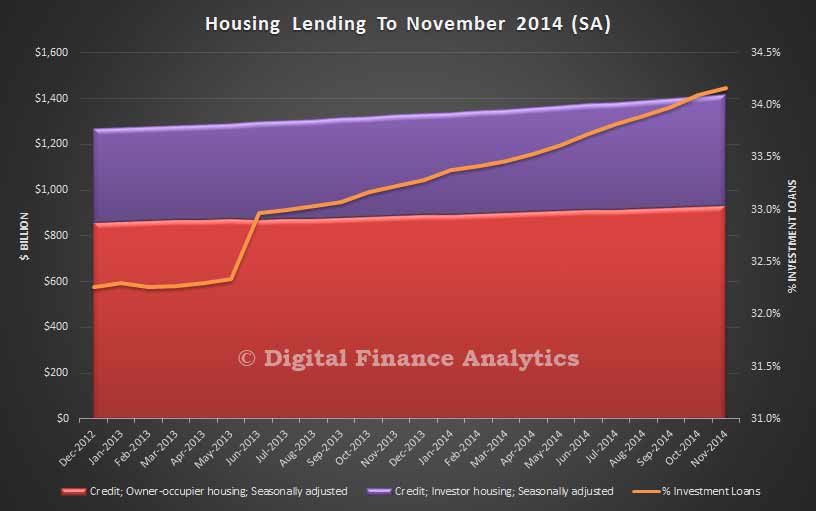

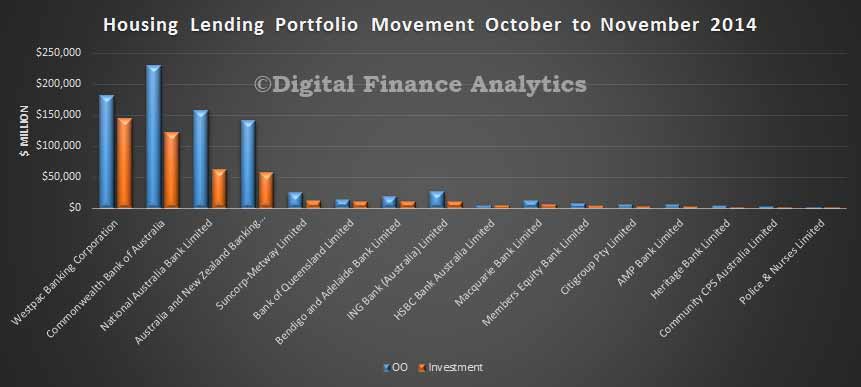

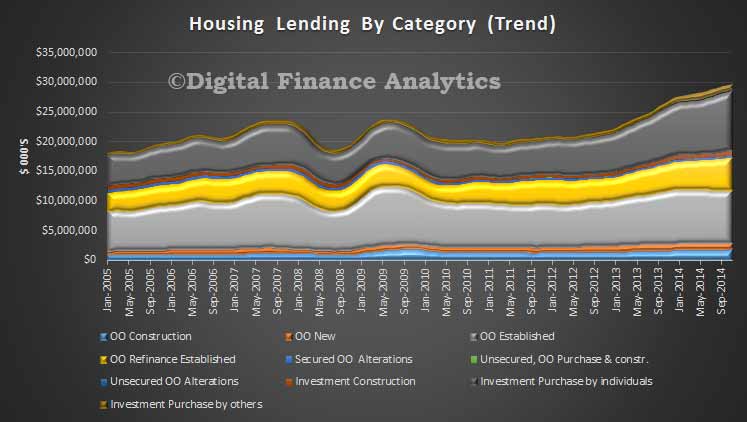

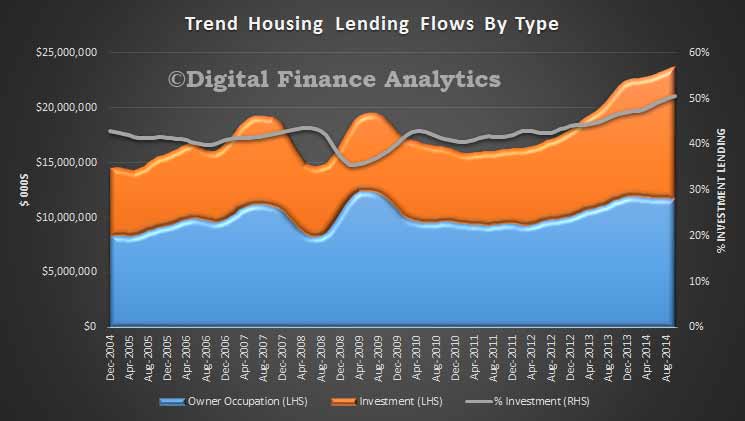

Looking specifically at the housing sector, the growth in investment lending stands out.

Looking specifically at the housing sector, the growth in investment lending stands out.

In fact in trend terms half of all lending was for investment purposes, a record.

In fact in trend terms half of all lending was for investment purposes, a record.

2015 should be the year when Government recognizes that it is time to act. The current settings will continue to risk financial stability and economic growth.

2015 should be the year when Government recognizes that it is time to act. The current settings will continue to risk financial stability and economic growth.