A Danish bank has dropped the hurdle below which they will charge negative interest rates on deposits.

Yes, people have to pay to hold their money at the bank.

We discuss the implications.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

A Danish bank has dropped the hurdle below which they will charge negative interest rates on deposits.

Yes, people have to pay to hold their money at the bank.

We discuss the implications.

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Contents

1:00 The Apprentice

2:45 OECD Economic Outlook

06:28 Fed and the Repo

09:10 Trade Wars

10:00 US Markets

12:30 Central Bank Divergence

13:00 Euro zone and Brexit

13:30 Deutsche Bank Sales

15:45 AP Property Exposures

17:00 New Zealand GDP

18:24 Australian Section

18:24 Latest economic data

19:40 Employment data

20:48 Scenarios

21:30 Property prices and auctions

26:00 War on Cash

33:40 Australian markets

35:50 Australian Bank derivatives

If today’s second consecutive repo was supposed to calm the stress in the secured lending market and ease the funding shortfall in the interbank market, it appears to have failed says Zerohedge.

As the WSJ said on Tuesday:

For the first time in more than a decade, the Federal Reserve injected cash into money markets Tuesday to pull down interest rates and said it would do so again Wednesday after technical factors led to a sudden shortfall of cash.

The pressures relate to shortages of funds banks face resulting from an increase in federal borrowing and the central bank’s decision to shrink the size of its securities holdings in recent years. It reduced these holdings by not buying new ones when they matured, effectively taking money out of the financial system.

Bloomberg said while the spike wasn’t evidence of any sort of imminent financial crisis, it highlighted how the Fed was losing control over short-term lending, one of its key tools for implementing monetary policy. It also indicated Wall Street is struggling to absorb record sales of Treasury debt to fund a swelling U.S. budget deficit. What’s more, many dealers have curtailed trading because of safeguards implemented after the 2008 crisis, making these markets more prone to volatility.

And Bloomberg today signals more intervention ahead.

The Federal Reserve made crystal clear that it doesn’t want U.S. money market rates to spike again like they did early this week, announcing it will — for the third day in a row — inject cash into this vital corner of finance.

On Thursday, the New York Fed will offer up to $75 billion in a so-called overnight repurchase agreement operation, adding another dose of temporary liquidity to restore order in the banking system. It made the same offer Tuesday and Wednesday, deploying a tool it hadn’t used in a decade. This latest action follows the Fed’s reduction in the interest rate on excess reserves, or IOER, another attempt to quell money-market stresses.

The prior operations have calmed markets, with repo rates declining Wednesday to more normal levels after jumping to 10% on Tuesday, four times where it was last week.

In addition, as Credit Swiss points out, Basel changed the rules:

The longer term issue is that the definition of “excess reserves” has changed in a Basel III environment. Previously excess reserves were defined by the Fed’s standard. If banks held more in the Federal Reserve accounts than they needed to settle transactions with one another, they had excess reserves. Now, under Basel III, excess reserves are defined by a global standard. Banks not only need enough reserves to settle accounts with one another at the end of each day – they also need to hold enough reserves for liquidity and capital buffer purposes. Indeed, reserves are better “high quality liquid assets” (HQLA) than even US Treasuries. In this context, at the beginning of 2017 (when Basel III really kicked in), banks found themselves with excess reserves by Fed standards, but deficient reserves by Basel III standards. Making matters worse for a little while were the Fed’s balance sheet reduction efforts, draining reserves from the system

This could be a signal of a potential liquidity crisis (echoes of 2007?).

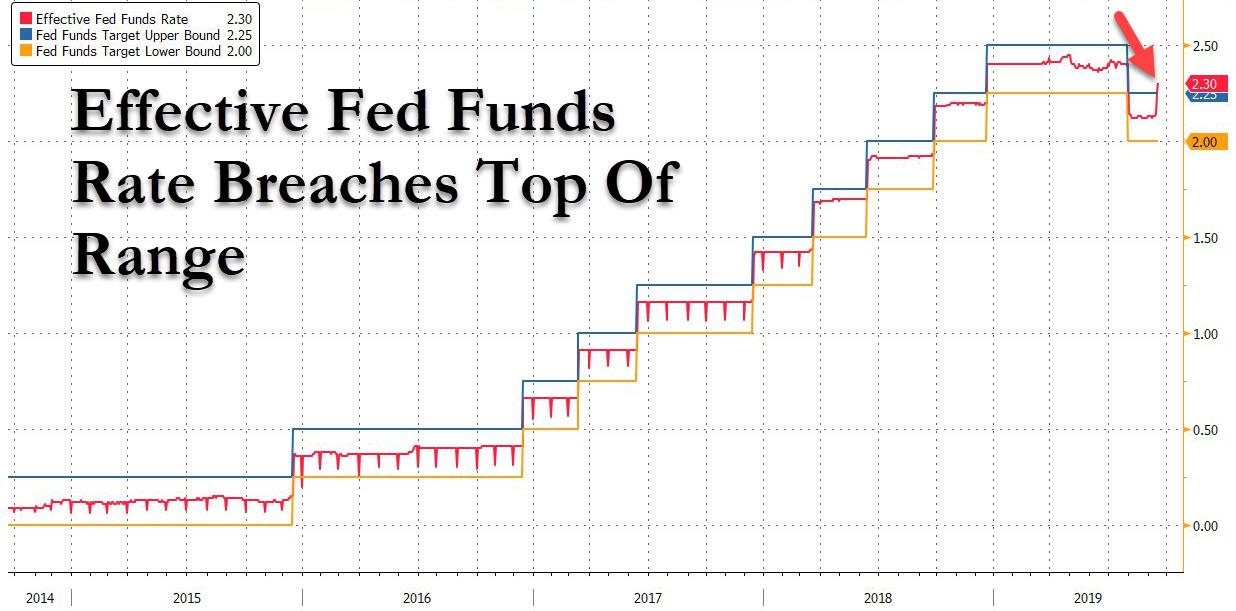

Zerohedge says not only did O/N general collateral print at 2.25-2.60% after the repo operation, confirming that repo rates remain inexplicably elevated even though everyone who had funding needs supposedly met them thanks to the Fed, but in a more troubling development, the Effective Fed Funds rate printed at 2.30% at 9am this morning, breaching the Fed’s target range of 2.00%-2.25% for the first time.

And yes, it is quite ironic that on the day the Fed is cutting rates, the Fed Funds was just “pushed” above the top end of the target range for the first time ever.

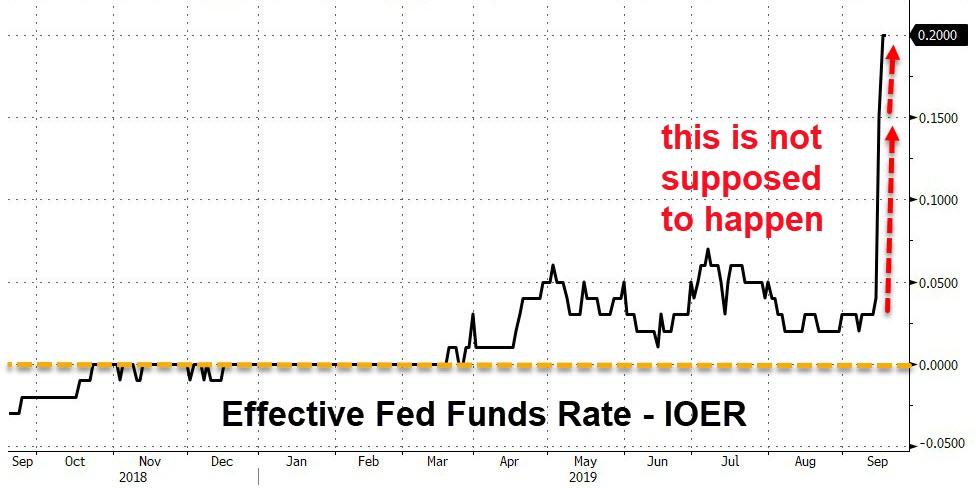

This also means that the EFF-IOER spread has now blown out to an unprecedented 20bps, yet another indication that the Fed has lost control of the rates corridor.

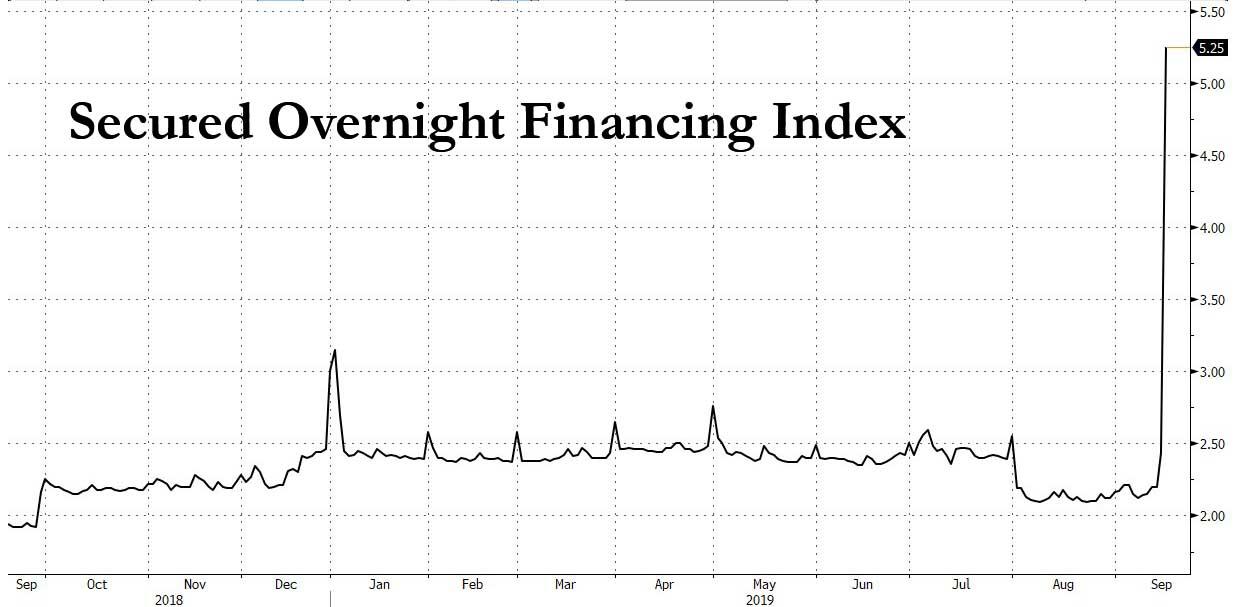

But in what may be the most concerning move, today’s print for the Secured Overnight Financing Index (SOFR), which is widely expected to be Libor’s replacement, exploded higher by 282bps to a record 5.25%.

Commenting on the blow out in the SOFR, Goldman had this to say on the “extremely volatile” price action in the key funding index:

The SOFR market saw extremely volatile price action over the course of the day…. Almost 20k in SERU9 blocks printed from 11:15am through the afternoon, pushing SERFFU9 from -10 to -21.5. Shortly after 4pm the market was given another jolt of adrenaline as news of a second Fed operation to be conducted tomorrow morning at 8:15am caused the spot-6mo curve to go bid into the close.

The problem here is that since SOFR is expected to replace LIBOR as the reference rate for several hundred trillions in fixed income securities, a spike such as this one would be perfectly sufficient to wreak havoc across market if indeed it had been the key reference rate.

Finally, courtesy of BMO’s Jon Hill, here is some commentary on today’s oversubscribed, and clearly insufficient, repo operation by the Fed:

Today’s emergency repo operation was oversubscribed with $51.6 bn in Treasury and $22.8 bn in MBS collateral accepted. The weighted average in USTs was 2.215%, with a high rate of 2.36% and a low of 2.10%. This should help alleviate some stress in USD funding markets, and the fact that it’s occurring earlier in the morning than Tuesday should help keep daily averages more subdued than yesterday – SOFR printed at a remarkable 5.25% (a stunning 282 bp spike) with fed funds still unknown but scheduled to be released at 9:00 AM ET and likely to print outside of the target range.

If Powell is successful at guiding the market toward assuming a mid-cycle adjustment, one specific repricing that will occur is in 2020 forwards, which are still factoring in one and a half 25 bp cuts next year as shown in the attached (admittedly, precision here is difficult due to the illiquidity of the Jan ’21 contract). This contrasts with the FOMC’s desire to execute a more modest drop in overnight rates and the price response here will be a focal point in determining how markets are responding to the impending Fed communication. If Powell is effective, look for that area of the curve to steepen sharply.

We ran our September 2019 live event last night with strong participation from our audience. During the show we discussed our updated scenarios (based on a starting point of August 2018) and answered a range of questions on property and finance.

The edited edition of the show is available to view in replay. This excludes the pre-show and live chat, but does include some behind the scene glimpses.

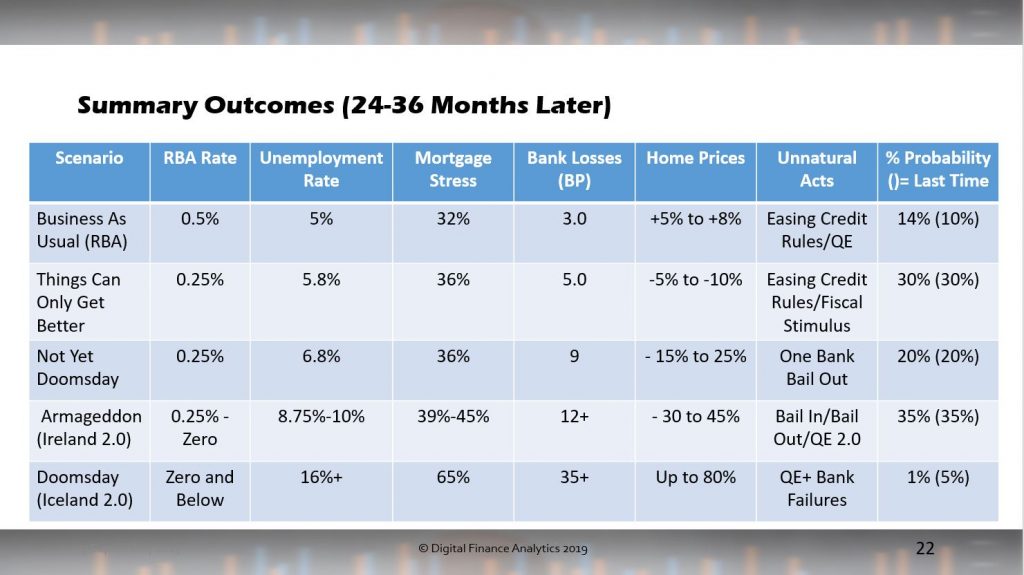

Our scenarios present a range of alternative outcomes, looking 2-3 years out. “Business As Usual” is based on the RBA’s view, with some tweaks – as we do not believe unemployment will fall to their target of 4.5%! Here there is a path to higher home prices, though with falls later as the current “recovery” reverses.

“Things Can Only Get Better” – is our view of the fading local economy without significant international economic disruption, with unemployment rising, as retail and construction slows, countered by additional Government intervention within their “surplus” limits. Here home prices fall once again.

“Not Yet Doomsday” is our scenario where international economic conditions deteriorate (China, US, Brexit Etc…) as global growth slows. This has a significant impact on the local economy and the spillover effects drive the Australian economy into recession. As liquidity pressures emerge one bank will need assistance.

“Armageddon” is where we get a GFC 2.0 type event, with global liquidity under pressure, and banks needing to be rescued by either bailing in or bailing out. The spillover impacts will be significant (as once again tax payers or households end up picking up the tab. More QE will follow.

Finally “Doomsday” would be the case where Central Banks and Governments allow banks to fail, with all the knock-on consequences.

As well as estimating the impact on unemployment and home prices we also weight the probability of each outcome. This is updated each month as new information arrives via our Core Market Model.

The original live stream recording is also available, with the show commencing at 30 mins in to allow for the live chat replay.

A quick reminder of our live stream event tomorrow, plus we share some new data on Australian sub-prime mortgages and refinancing.

An important discussion about credit creation, why banks are talking interest rates down, and what economists are prepared to say and what they are not, courtesy of Joe Wilkes. Refers to my earlier post:

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Contents:

1:14 US

2:38 Powell In Switzerland

9:15 US Markets

14:00 Europe

16:49 China

18:32 Australia

19:09 Retail

19:55 DFA FCI

20:45 Trade

21:00 RBA Monetary Policy

22:08 GDP

25:00 DFA and the media

29:00 Property prices and auctions

32:00 Outlook

34:30 Market summary

Links:

Be Aware Of Australia’s Soviet Liberal Government!

Nuggets News: Monthly housing and market update

Peter Switzer:

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Contents:

1:11 – US Markets

4:25 – Bond Rates

5:29 – Q2 Earnings

6:40 – UK

7:51 – Europe

8:49 – Argentina

9:44 – Australian Section

10:00 – GDP Guidance

11:12 – Home Prices

16:56 – Auction Results

18:16 – Credit

19:52 – Construction

20:41 – Australian Markets

23:28 – Cash Ban

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Contents:

Global Scene: 0.00 – Trade Wars: 1:08 – Gold: 8:00 – New Reserve Digital Currency: 10:51 – Global Markets: 15:30 Australia: 17:41 – Property Auction And Prices: 18:28 – First Time Buyers: 25:45 – Building Defects: 27:15 – Economic Data: 33:28 – Local Markets; 37:20 – Cash Ban: 43:45

We ran out live stream event last night. During the session we discussed our revised scenarios, taking account of the complex local and international backdrop.

Using a baseline of July 2018, and looking ahead this is how it plays out. The risks from an international crisis have risen, the RBA itself is now projecting higher unemployment so lower wages growth, and the iron ore price is falling. Business and consumer confidence is being eroded, and the fall-out from the high-rise construction fiasco are only just starting to play out.

There is a path to property values rising, but we think this is relatively short lived.

You can watch the edited edition of our show, complete with some behind the scenes views.

Or watch the original streamed version with the pre-show, and live chat.

The show proper starts at 30:02.