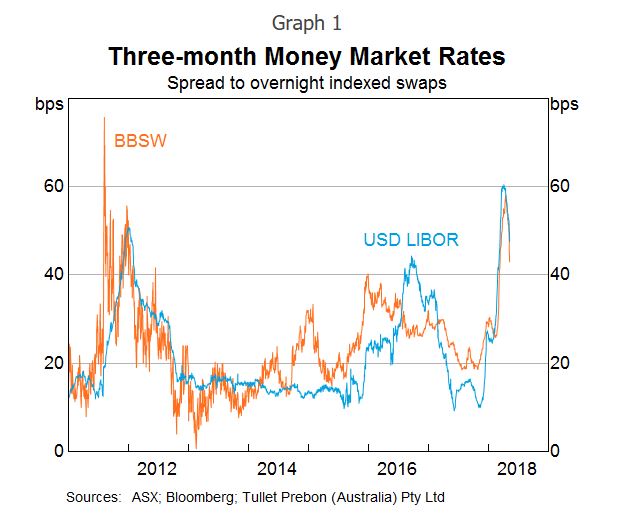

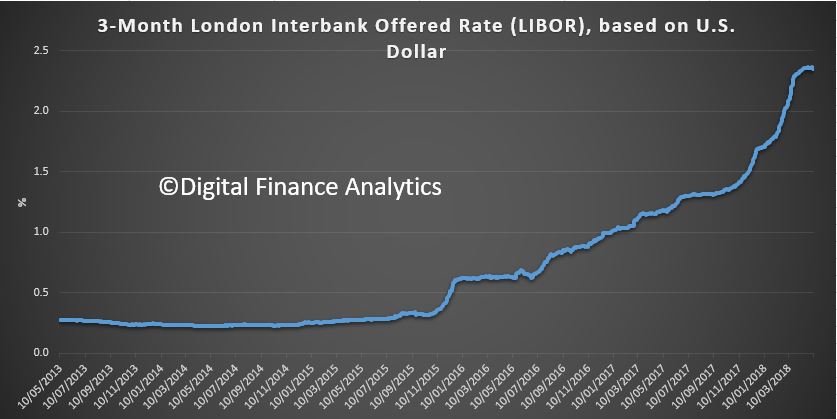

The cost of money continues to rise, and this includes the LIBOR benchmark rate, as shown by this chart. LIBOR or ICE LIBOR (previously BBA LIBOR) is a benchmark rate that some of the world’s leading banks charge each other for short-term loans. As it climbs, it signals rate rises ahead.

But what is LIBOR, and more importantly, will it survive?

But what is LIBOR, and more importantly, will it survive?

ICE LIBOR stands for Intercontinental Exchange London Interbank Offered Rate and serves as the first step to calculating interest rates on various loans throughout the world. LIBOR is administered by the ICE Benchmark Administration (IBA) and is based on five currencies: the U.S. dollar (USD), euro (EUR), pound sterling (GBP), Japanese yen (JPY), and Swiss franc (CHF). The LIBOR serves seven different maturities: overnight, one week, and 1, 2, 3, 6 and 12 months. There is a total of 35 different LIBOR rates each business day. The most commonly quoted rate is the three-month U.S. dollar rate (usually referred to as the “current LIBOR rate”), as shown in the chart.

So, LIBOR is the key interest rate benchmark for several major currencies, including the US dollar and British pound and is referenced in around US$350 trillion worth of contracts globally. A large share of these contracts have short durations, often three months or less. But it’s up for a shakeout as RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle Discussed recently.

Last year, the UK Financial Conduct Authority raised some serious questions about the sustainability of LIBOR. That is, apart from the rate fixing problems and the ensuing large fines.

The key problem is that there are not enough transactions in the short-term interbank funding market to reliably calculate the benchmark. In fact, the banks that make the submissions used to calculate LIBOR are uncomfortable about continuing to do this, as they have to rely mainly on their ‘expert judgment’ in determining where LIBOR should be rather than on actual transactions. To prevent LIBOR from abruptly ceasing to exist, the FCA has received assurances from the current banks on the LIBOR panel that they will continue to submit their estimates to sustain LIBOR until the end of 2021. But beyond that point, there is no guarantee that LIBOR will continue to exist. The FCA will not compel banks to provide submissions and the panel banks may not voluntarily continue to do so. There is no guarantee at all that will be the case.

So market participants that use LIBOR need to work on transitioning their contracts to alternative reference rates. The transition will involve a substantial amount of work for users of LIBOR, both to amend contracts and update systems. The process is not straightforward. A large share of these contracts have short durations, so these will roll off well ahead of 2021, but they should not continue to be replaced with another short-dated contract referencing LIBOR. A very sizeable number of current contracts would extend beyond 2021, with some lasting as long as 100 years.

So regulators around the world have been working closely with the industry to identify alternative risk-free rates that can be used instead of LIBOR. These alternative rates are based on overnight funding markets since there are plenty of transactions in these markets to calculate robust benchmarks. Last month, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York began publishing the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) as the recommended alternative to US dollar LIBOR. For the British pound, SONIA has been identified as the alternative risk-free rate, and the Bank of England has recently put in place reforms to ensure that it remains a robust benchmark.

But these chosen risk-free rates are overnight rates, while the LIBOR benchmarks are term rates. Some market participants would prefer for the LIBOR replacements to also be term rates. While the development of term risk-free rates is on the long-term agenda for some currencies, they are unlikely to be available anytime soon. This reflects that there are currently not enough transactions in markets for term risk-free rates – such as overnight indexed swaps (OIS) – to support robust benchmarks. Given this reality, it is very important that users of LIBOR are planning their transition to the overnight risk-free benchmarks that are available, such as SOFR for the US dollar and SONIA for the British pound.

For the risk-free rates to provide an alternative to LIBOR, the next challenge is to generate sufficient liquidity in derivative products that reference the risk-free rates. This will take some time, particularly for the US dollar, where SOFR only recently started being published. Nevertheless, progress is being made, with the first futures contracts referencing SOFR recently being launched.

Market participants also need to be prepared for a scenario where the LIBOR benchmarks abruptly cease to be published. In such an event, users would have to rely on the fall-back provisions in their contracts. However, for many products the existing fall-back provisions would be cumbersome to apply and could generate significant market disruption. For instance, some existing fall-backs involve calling reference banks and asking them to quote a rate. To address this risk, the Financial Stability Board has encouraged ISDA to work with market participants to develop a more suitable fall-back methodology, using the risk-free rates that have been identified. But LIBOR is very different from an overnight risk-free rate as it includes bank credit risk and is a term rate. So the key challenge is to agree on a standard methodology for calculating credit and term spreads that can be added to the risk-free rate to construct a fall-back for LIBOR. This needs to be resolved as soon as possible, and we encourage users of LIBOR to engage with ISDA on this important work.

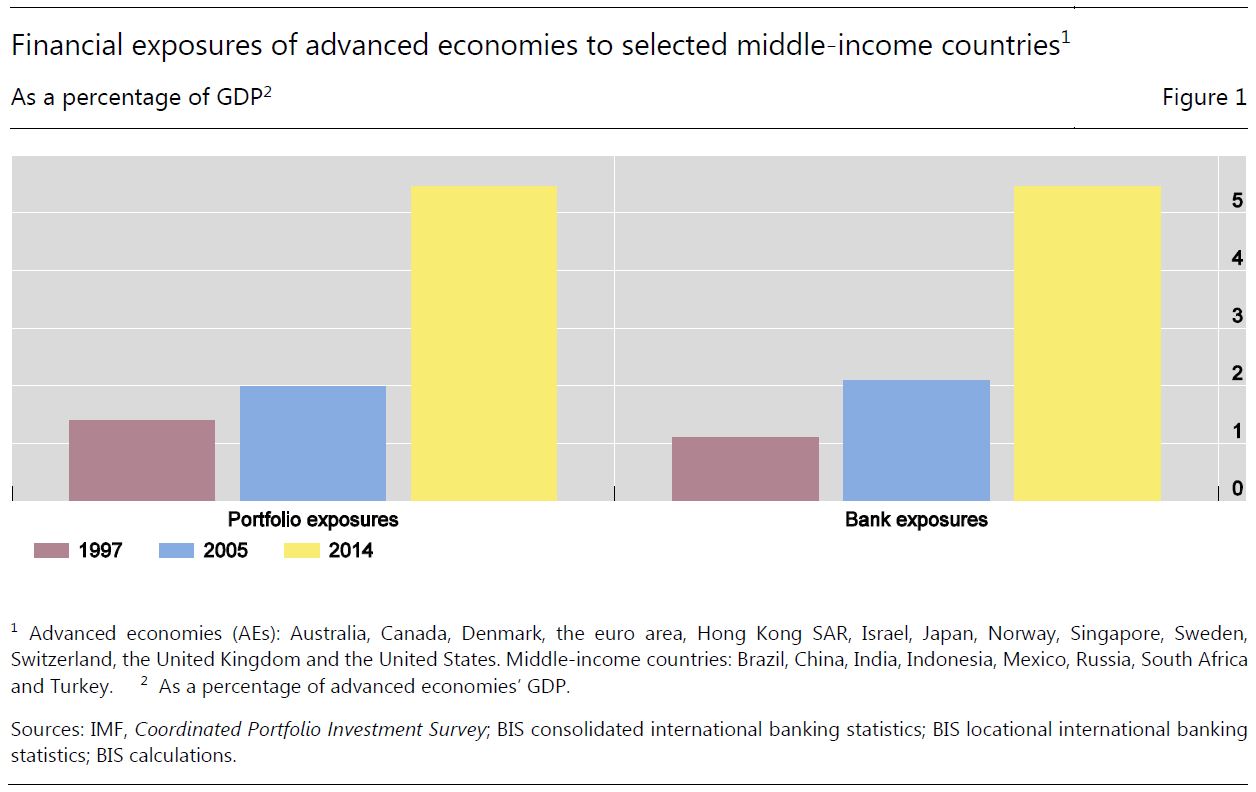

Finally, In Australia, the key InterBank Offer Rate benchmark for the Australian dollar is BBSW. Again we saw a spate of rate manipulations around BBSW, but the RBA and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) have been working closely with industry to ensure that it remains robust. The RBA argues the critical difference between BBSW and LIBOR is that there are enough transactions in the local bank bill market each day to calculate a robust benchmark. Australia has an active bank bill market, where the major banks issue bills as a regular source of funding, and a wide range of wholesale investors purchase bills as a liquid cash management product.

They think that BBSW can continue to exist even if credit-based benchmarks, such as LIBOR, are discontinued in other jurisdictions. But in the event that LIBOR was to be discontinued, with contracts transitioning to risk-free rates, there may be some corresponding migration away from BBSW towards the cash rate. This will depend on how international markets for products such as derivatives and syndicated loans end up adapting in a post-LIBOR world.

The infrastructure is already in place for BBSW and the cash rate to coexist as the key interest rate benchmarks for the Australian dollar. The OIS market is linked to the cash rate and has been operating for almost 20 years. It already has good liquidity at the short end, and the infrastructure is there for longer term OIS. A functioning derivatives market for trading the basis between the benchmarks is important for BBSW and the cash rate to smoothly coexist. Such a basis swap market is also in place, allowing market participants to exchange the cash flows under these benchmarks.

So the bottom line is that these Interbank Offer Rates are not as immutable as might be imagined, and this uncertainty is likely to continue for some time to come.