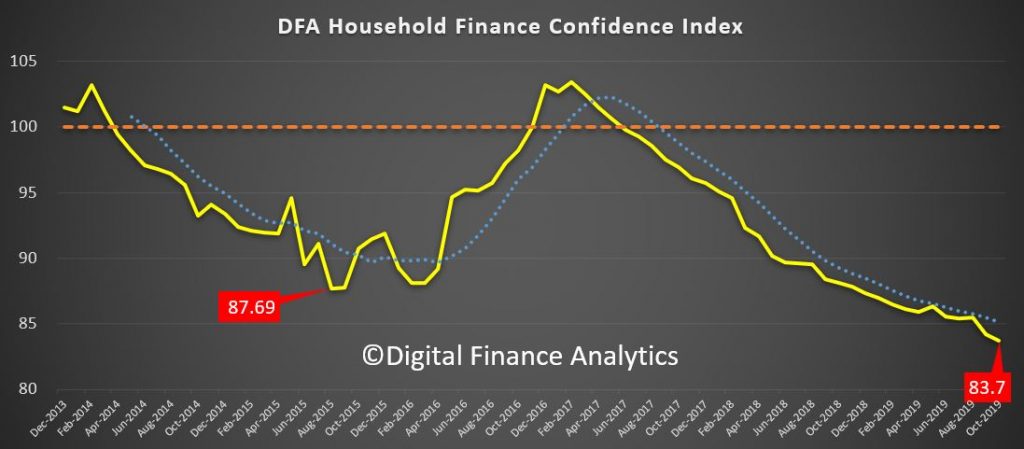

The bad news keeps coming, with the latest DFA Household Financial Confidence Index for October at the lowest ever of 83.7.

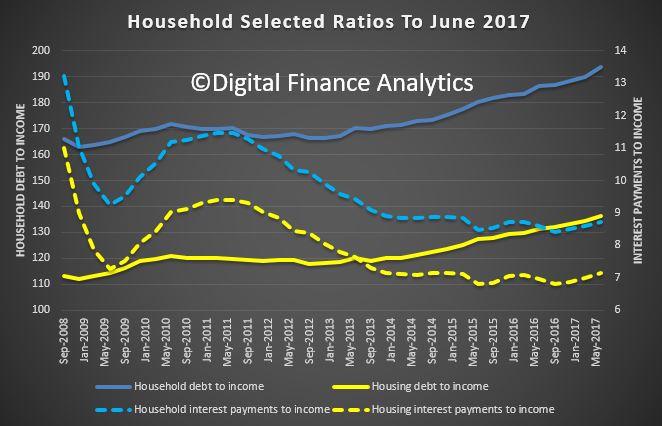

This continues the trends of recent months, since dropping through the neutral 100 score in June 2017.

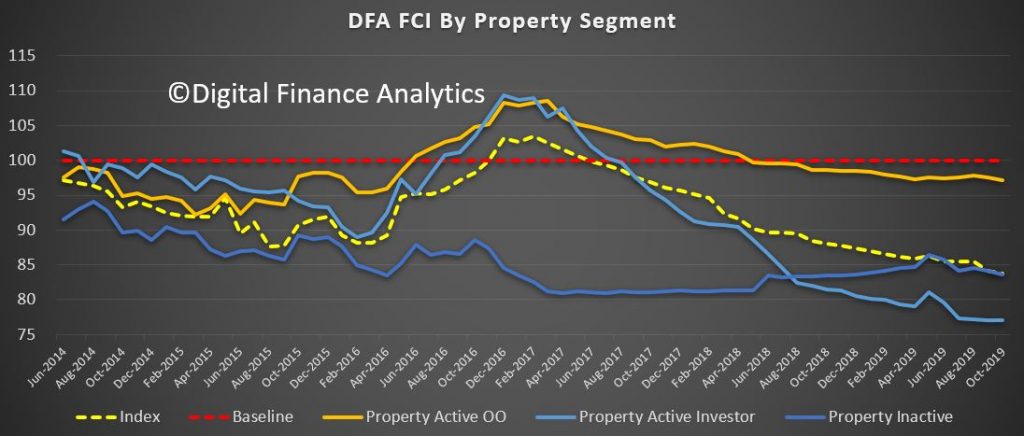

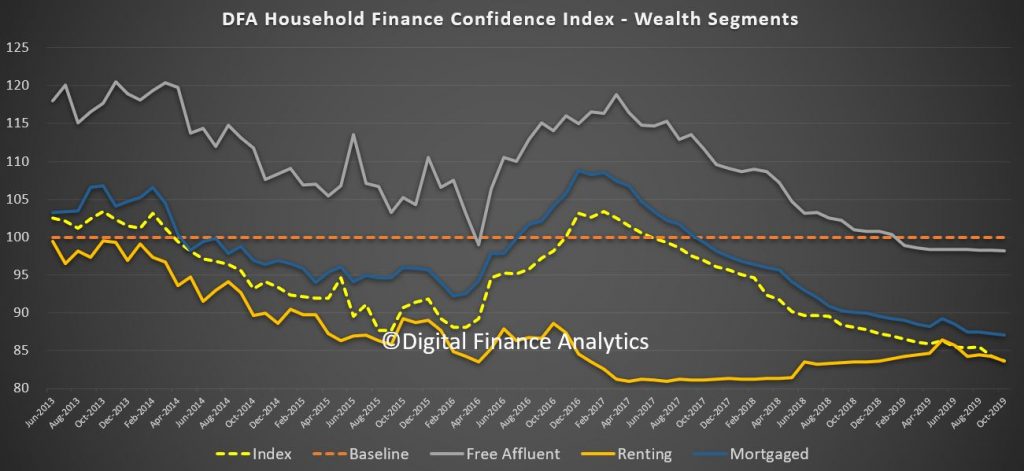

The falls were widespread across our property segments, with investors still way down, under the pressure from low net rental yields, the need to switch to principal and interest from interest only, and worries about construction defects. Owner occupied households were less negative, but those renting continue to struggle with higher levels of rental stress.

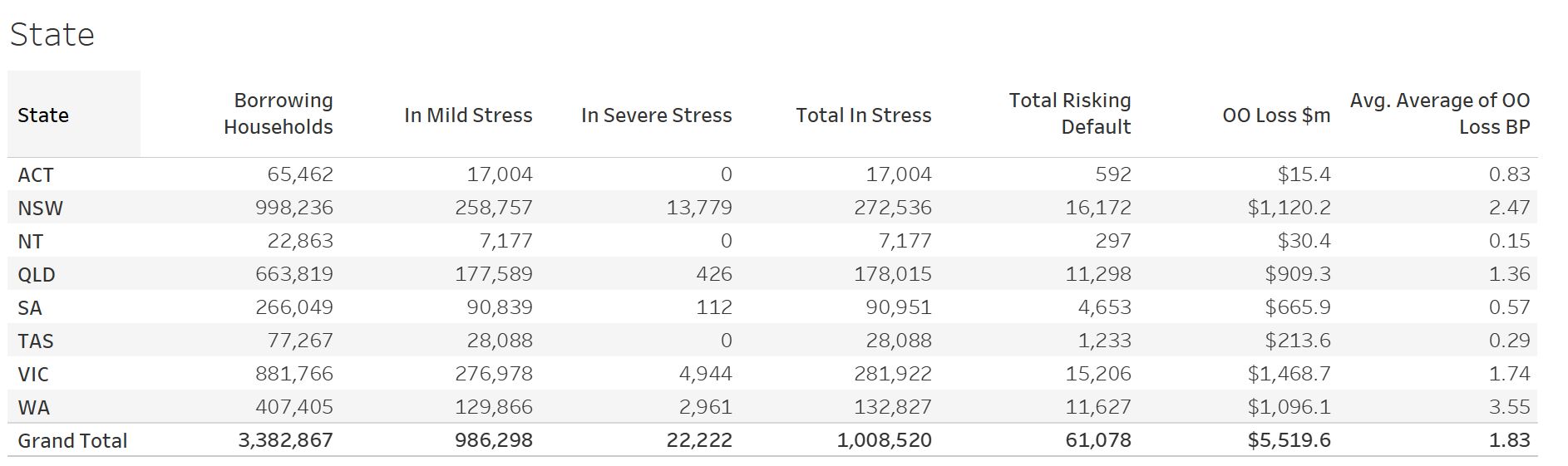

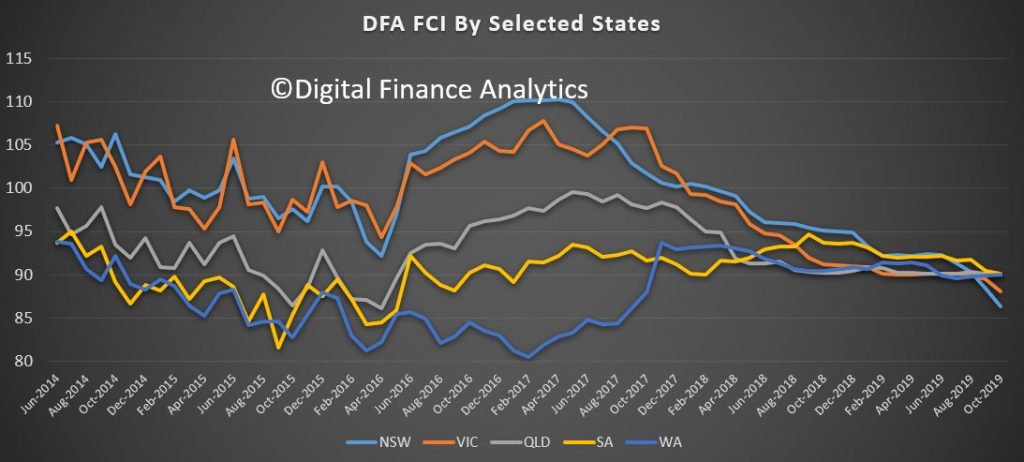

Across the states there were significant falls in NSW and VIC, whilst other states continued to track as in recent months. The main eastern states are now lower than WA and SA, which is a surprising new development.

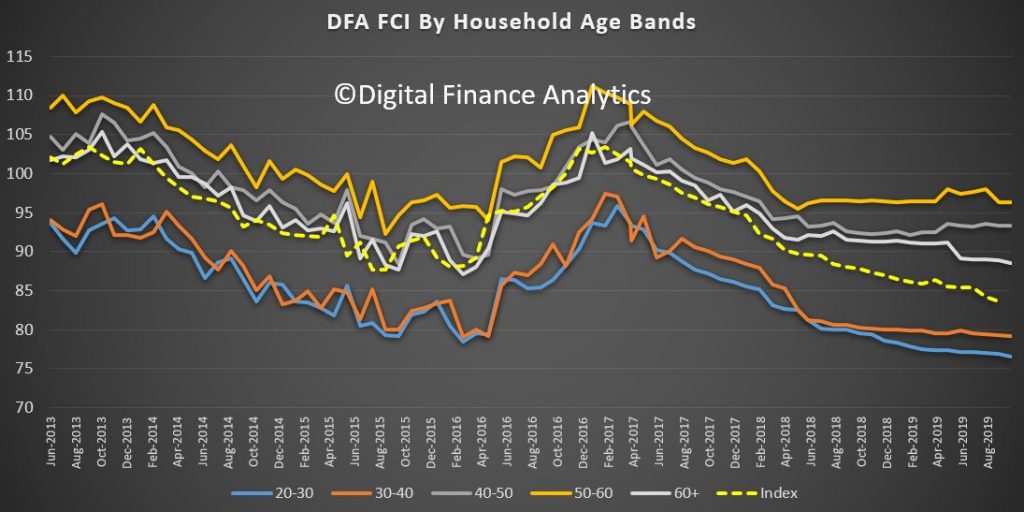

Across the age bands, the falls are mainly among lower aged groups, while those aged 50-60 are feeling more positive thanks to recent stock market rises.

This is also reflected across our wealth segments, with those holding property mortgage free and other financial assets more positive (though still below neutral) compared with mortgage holders and those not holding property at all.

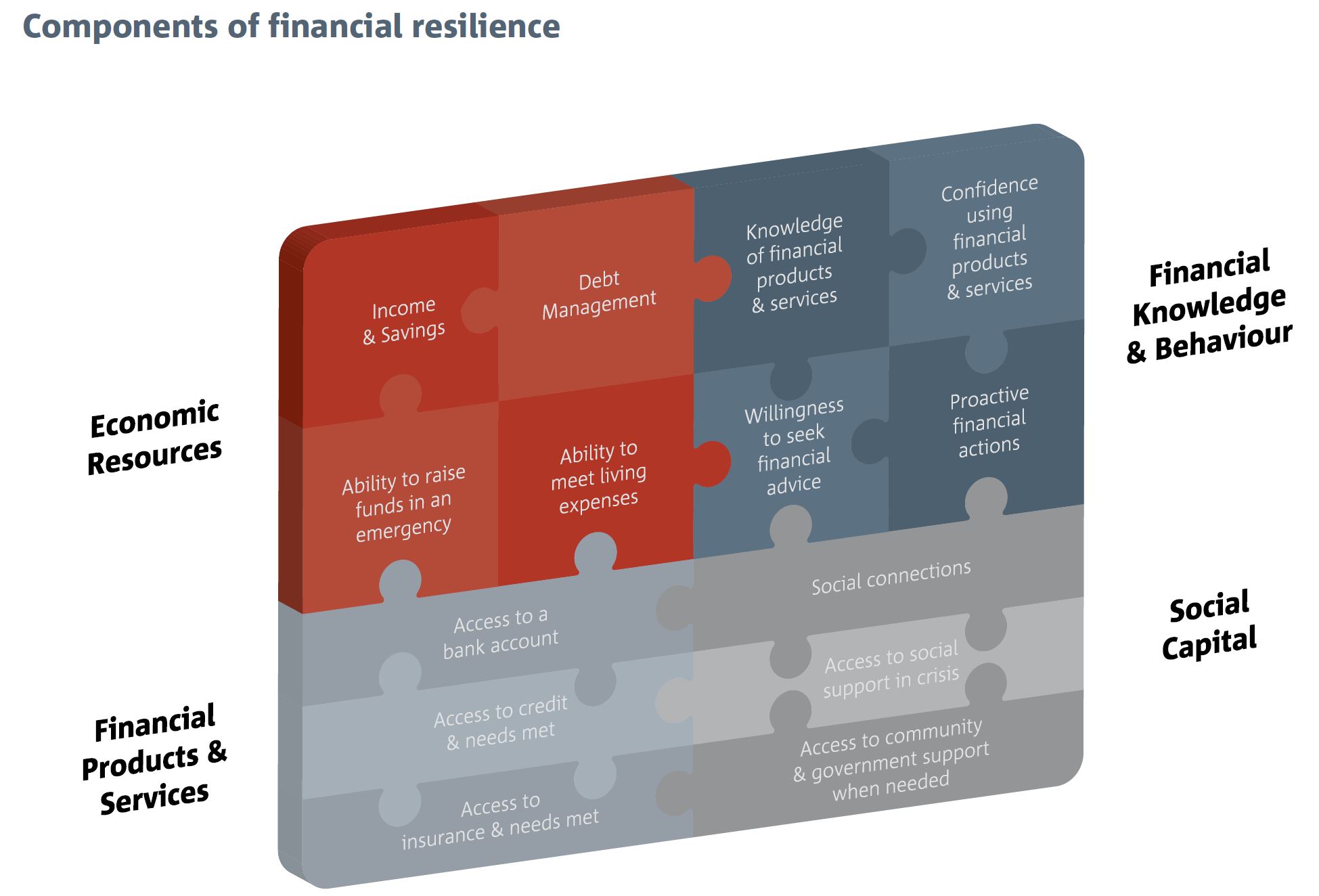

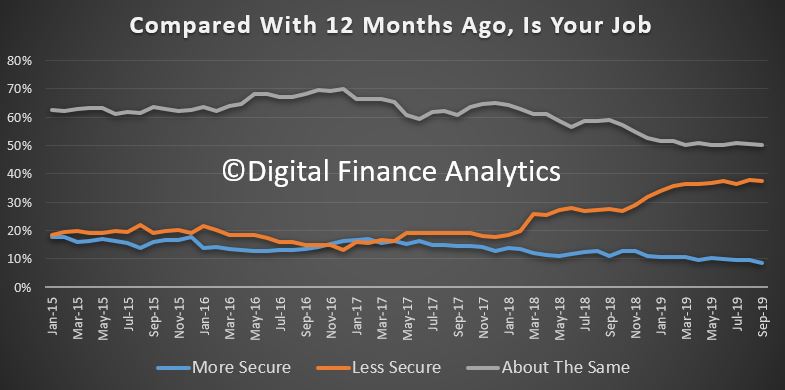

We can then turn to the moving parts within the index, based on our rolling 52,000 household surveys. Employment prospects continue to look shaky, both in terms of under-employment and job security. Jobs in retail and construction and also finance are under-pressure, and the impact of the drought is also hitting some areas. 8% of household felt more secure than a year ago, the lowest read ever in this part of the survey. More households have multiple part-time jobs.

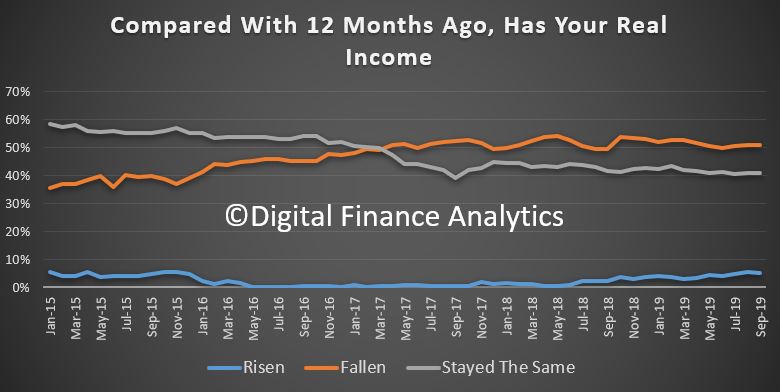

Income remains under pressure, with 51% saying their real incomes have fallen in the past year, while 5% reported an increase, often thanks to switching jobs or employers.

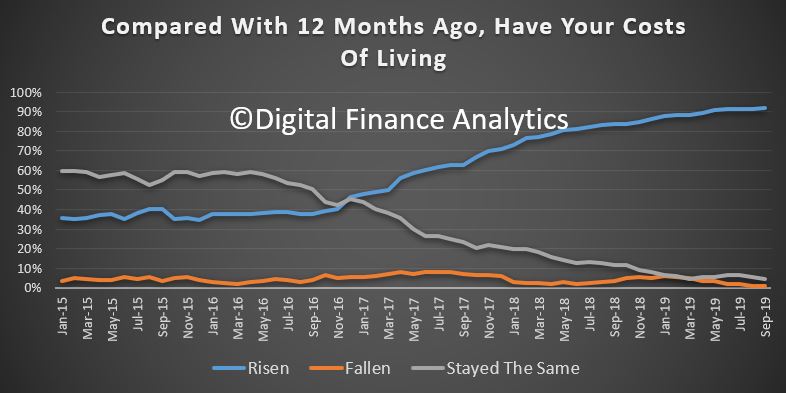

Household budgets are under pressure as costs of living rise, with 91% reporting higher real costs that a year ago, this is a record in our survey. Expenses rose across the board, from child care, health care, school fees and rates. Food costs were higher partly thanks to the drought. There was a small fall in the costs of power, and fuel, but not enough to offset rises elsewhere. Mortgage interest rate falls were blotted up quickly, and the tax refunds where they were received were much lower than people had been expecting.

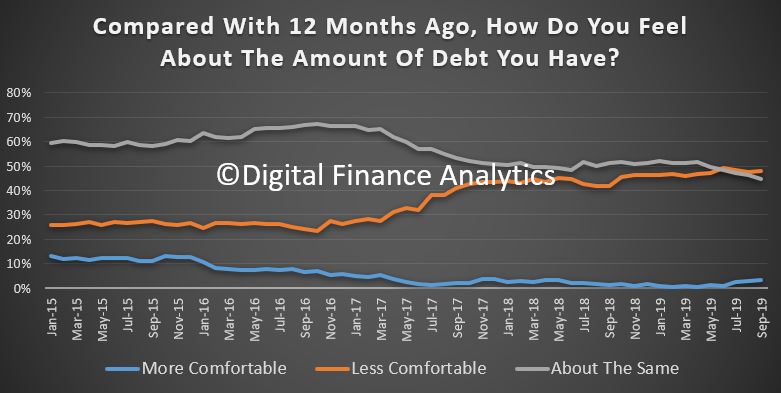

Some households are deleveraging (paying down debt) , while others are more concerned about the amount they owe from mortgages to credit cards and on other forms of credit. 48% of households are less comfortable than a year ago. Lower interest rates are only helping at the margin.

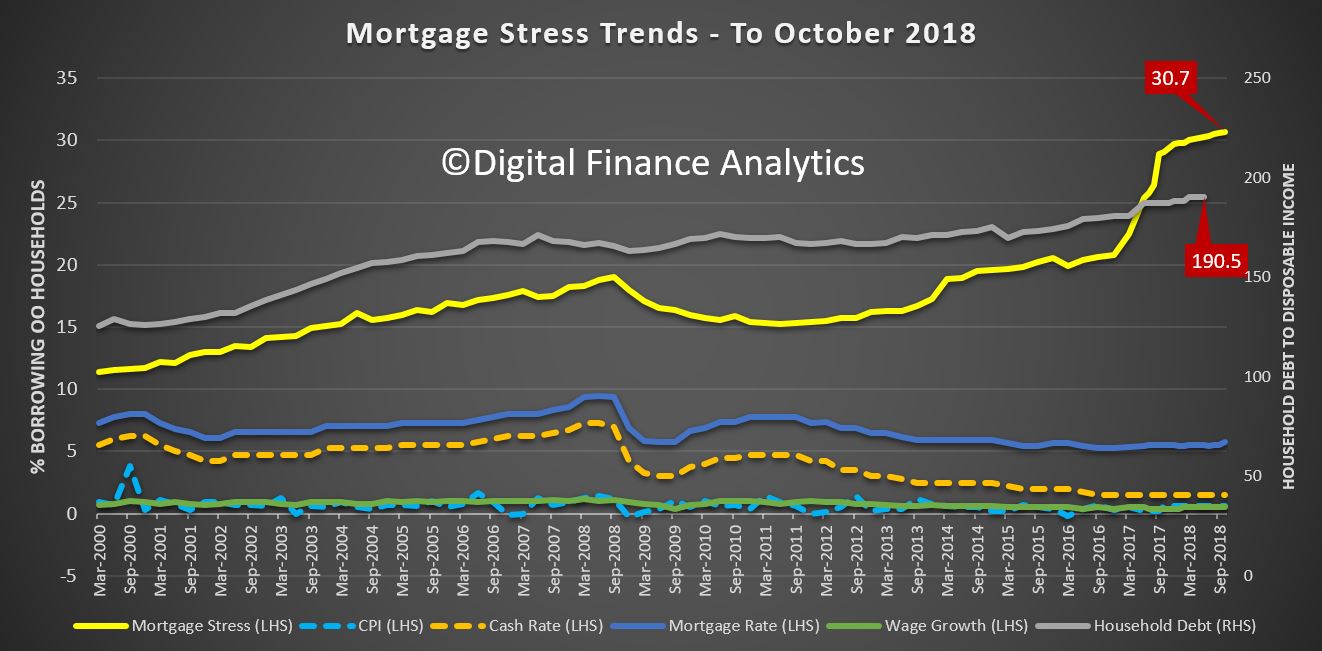

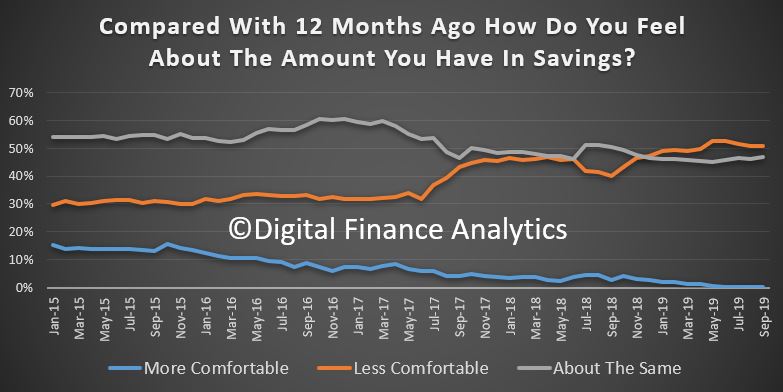

Savings are under pressure from several fronts. Some households are tapping into savings to keep the household budget in check – but that will not be sustainable. Others are seeing returns on term deposits falling away, yet are unwilling to move into higher-risk investment assets. Those in the share markets are enjoying the current bounce, but many expressed concerns about its sustainability. 49% of households are less comfortable than a year ago, while 47% are about the same. Significantly around 27% of households have no savings at all and would have difficulty in pulling $500 together in an emergency. Around half of these households also hold a mortgage. Worth reflecting on this with 32.2% of households in mortgage stress as we also reported today!

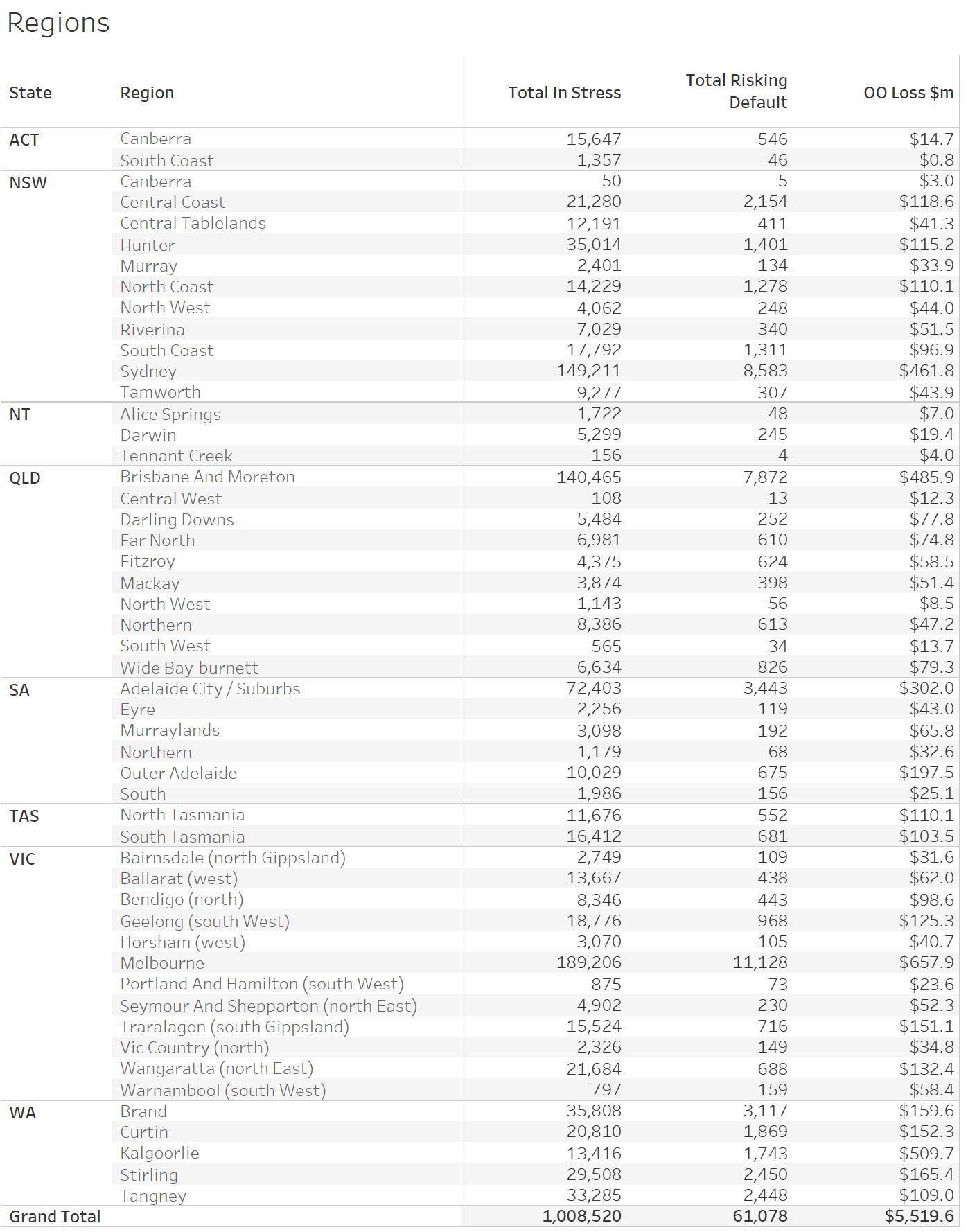

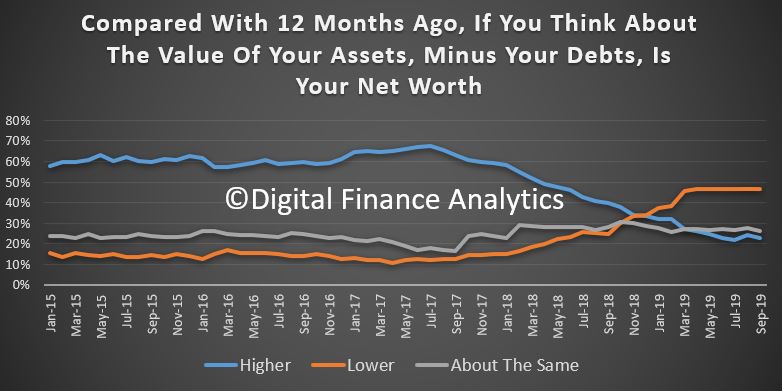

And finally, we consider net worth (assets less liabilities). Here the news is mixed as some households are now convinced their property is worth more citing the recently if narrowly sourced data on rises in Sydney and Melbourne. However other households reported net falls. 24% of households said their net financial position was better than a year ago (up 1.3%), while 45% said they were worse off (down 1.6%). There are also significant regional differences with households in Western Australia and Queensland significantly worse off, while some in inner city areas of Sydney and Melbourne claimed significant advances.

So, overall the status of household confidence continues to weaken, which is consistent with reduced retail activity, and a focus on repaying debt. Unemployment is lurking, but underemployment is real. We also see weaker demand for mortgages ahead, and we will discuss this in more detail in our upcoming household survey release. Without significant economic change, these trends are likely to continue for some time. If the RBA and Government is relying on households to start spending, they will need a very different strategy – including a significant fiscal element. Lower interest rates alone will not cut the mustard.