We discussed aspects of the FSI Report on the ABC Drum recently. You can view the programme via the ABC iView feature. Points we touched on included the changes to capital and the bank’s responses, why more capital is needed, financial adviser disclosure, regulatory frameworks and the need for cultural change.

Category: General Discussion

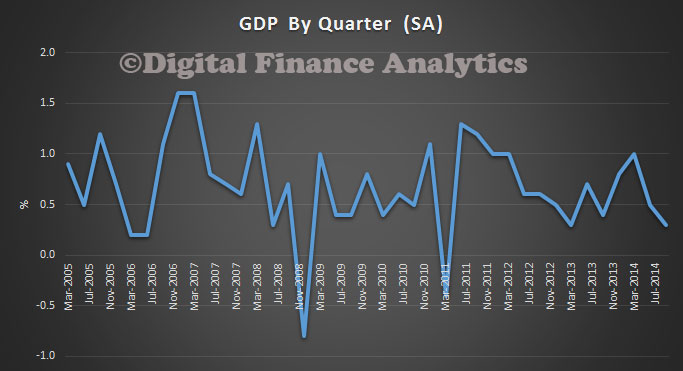

GDP 0.3% In Sept Quarter

The ABS published their data to September 2014 in the National Accounts. GDP, in seasonally adjusted chain volume terms, grew 0.3 per cent in the September quarter 2014. This number is significantly below analysts’ expectations which was in the order of 0.7 per cent in the quarter and also is a drop from the relatively weak 0.5% growth recorded in June.This translates to 2.7 per cent for the 12 months to September 2014.

Net exports contributed 0.8 percentage points to GDP growth. Household final consumption expenditure contributed 0.3 percentage points to GDP growth and Government final consumption expenditure contributed 0.1 percentage points to GDP growth. This was offset by a -0.7 percentage point contribution to GDP growth from total Gross fixed capital formation and a -0.1 percentage point contribution from Changes in inventories.

The Terms of trade decreased 3.5%, and Real gross domestic income decreased 0.4%. In seasonally adjusted terms, the main contributors to the increase in expenditure on GDP were Net exports (0.8 percentage points) and Final consumption expenditure (0.4 percentage points) The main detractors were Private gross fixed capital formation (-0.5 percentage points) and Public gross fixed capital formation (-0.2 percentage points).

In seasonally adjusted terms, the main contributor to GDP growth was Financial and insurance services (0.2 percentage points), with Mining and Information media and telecommunications each contributing 0.1 percentage points to the increase in GDP. The main detractors to growth in GDP were Construction (-0.2 percentage points) and Professional, scientific and technical services (-0.2 percentage points).

In seasonally adjusted terms, the main contributor to GDP growth was Financial and insurance services (0.2 percentage points), with Mining and Information media and telecommunications each contributing 0.1 percentage points to the increase in GDP. The main detractors to growth in GDP were Construction (-0.2 percentage points) and Professional, scientific and technical services (-0.2 percentage points).

The AU – US rate dropped below 84c on the news.

OECD Warns Again On Housing

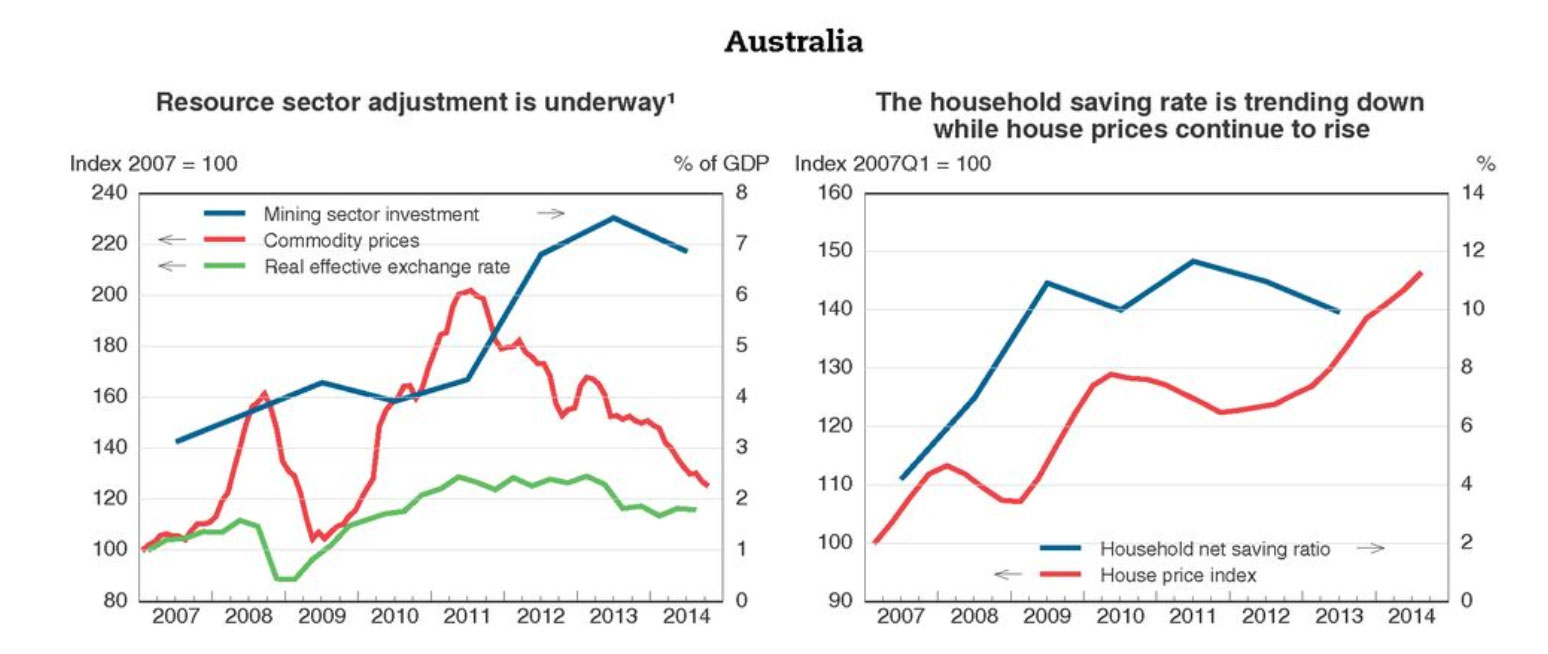

The OECD Economic Outlook 2014 Issue 2 has been released in a preliminary version. There are some important warnings which the RBA should heed. Essentially, OECD is highlighting again the risks in the current RBA policy of using low interest rates to drive housing growth in lieu of mining investment. They appear to believe rates should be taken higher and additional prudential measures should be taken.

Output growth is projected to dip to 2.5% in 2015 but recover to 3% in 2016. Declining business investment will be countered by gathering momentum in consumption and exports. Growth at the projected pace will be enough to lower the unemployment rate, although consumer price inflation will remain moderate due to economic slack.

Fiscal policy should continue to aim for a budget surplus by the early 2020s but given economic uncertainties, it should avoid heavy front loading. Short of negative surprises, withdrawal of monetary stimulus should start in the second quarter of 2015. The booming housing market and mortgage lending will require close attention by the authorities. There is room for both fiscal and monetary policy to provide support in the event of unexpected negative economic shocks.

The Australian economy is going through a period of adjustment as activity has to shift from the previously booming resource sector. Cooling commodity prices and declining resource-sector investment have resulted in job and output losses, but a lower exchange rate is lifting employment and exports elsewhere in the economy. House price increases are encouraging construction and consumption, but are also a concern in that a sharp reversal could cut aggregate domestic demand.

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA’s) policy rate has remained at 2.5% since August 2013, well below historical norms. Though helping economic adjustment, this monetary support has intensified search for returns by investors. This requires close oversight of asset-market developments, particularly rising housing credit, which is now being driven by investors. Further prudential measures on mortgage lending should be considered as a targetted means to cool the market, thereby heading off risks to financial stability.

External risks remain prominent, with recent steep falls in some commodity prices exemplifying the potential for rapit change in resource revenues. Domestically, the momentum in property prices is uncertain and could unwind sharply. When and how quickly non-0mining investment picks up is uncertain, as is the degree to which households will dip further into savings to sustain their consumption.

UK Banks To Improve Complaints Procedures

The UK FCA has completed an assessment of the complaints processes at 15 major retail financial firms – seven banks, two building societies, three general insurers and three life insurers – using hypothetical customer complaints. According to the results of the research, the firms chosen accounted for 79% of banking complaints, 60% of home finance complaints, 26% of general insurance complaints (excluding PPI), 42% of life insurance complaints and 42% of investment complaints reported to the FCA’s predecessor the Financial Services Authority between July and December 2012.

The review was conducted by a working group made up of the 15 participant firms and five trade bodies. The FCA also sought the views of the Financial Ombudsman Service and consumer groups.

“We asked firms to carry out self-assessments to better understand how complaints are dealt with in practice, as well as providing their documented policies, processes and management information (MI) for our review. We also established, and chaired, a working group of the participant firms and trade bodies to identify and discuss common complaint-handling issues. Our approach provided valuable insight into how firms manage their complaint functions. This allowed us to observe any barriers to effective complaint handling.”

But while the FCA found some improvements have already been made, such as senior management becoming more engaged with complaint handling and firms empowering staff to make the right judgements and to demonstrate empathy, the review also identified areas requiring further improvement. For example:

- Firms do not always consider the impact on consumers when designing and implementing processes and procedures.

- There are inconsistencies in the amount of redress offered, particularly for distress and inconvenience.

- Firms take a narrow approach to determining and fixing the underlying reason for a complaint, which may affect their awareness of wider issues.

The FCA is asking all financial firms, not just those that took part in the review, to consider the findings and to ensure their complaints procedures “have the interests of consumers at their heart”.

The working group also recommended changes to FCA rules on complaint handling, such as ensuring all complaints are reported to the regulator rather than just those that take longer than one working day to resolve. The FCA is now considering these recommendations and will consult on possible policy changes.

UK Banks Fined For IT Failures

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) is today fining Royal Bank of Scotland Plc (RBS), National Westminster Bank Plc (Natwest) and Ulster Bank Ltd (Ulster Bank) £14 million for inadequate systems and controls which led to a serious IT incident in 2012. This is the first financial penalty the PRA has imposed since it came into being in April 2013. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has separately fined the banks for the same incident.

In April 2013, the PRA and FCA announced that they would investigate the RBS, Natwest and Ulster Bank IT incident which led to widespread disruption to customers and the financial system. A joint investigation was considered necessary because the incident impacted upon the objectives of both the PRA and the FCA.

The IT incident, which began on 18 June 2012, directly affected at least 6.5 million customers in the United Kingdom, 92% of whom were retail customers. The IT incident had the potential to have an adverse effect on the safety and soundness of RBS, Natwest and Ulster Bank as it impacted upon:

- the ability of the banks’ retail customers to access their accounts;

- the ability of the banks’ commercial customers to access their internet banking service, preventing them from accessing their accounts or making payments;

- customers of other institutions who were unable to receive payments from the banks’ affected customers; and

- the ability of the banks to fully participate in clearing. An efficient clearing system is fundamental to the efficient operation of the financial markets.

Disruption to the majority of RBS and Natwest systems lasted until 26 June 2012, and Ulster Bank systems until 10 July 2012. Disruptions to other systems continued into July 2012. The cause of the IT incident was the failure of the banks to have the proper controls in place to identify and manage exposure to the IT risks within their business.

Properly functioning IT risk management systems and controls are an integral part of a firm’s safety and soundness. The PRA considers that the IT incident could have threatened the safety and soundness of the banks and could have, in extremis, had adverse effects on the stability of the financial system in that it interfered with the provision of the banks’ core banking functions, impacted third parties and risked disrupting the clearing system.

Andrew Bailey, Deputy Governor, Prudential Regulation, Bank of England and CEO of the PRA said:

“The severe disruption experienced by RBS, Natwest and Ulster Bank in June and July 2012 revealed a very poor legacy of IT resilience and inadequate management of IT risks. It is crucial that RBS, Natwest and Ulster Bank fix the underlying problems that have been identified to avoid threatening the safety and soundness of the banks.”

The banks agreed to settle at an early stage and were therefore entitled to a 30% discount, without which they would have been fined £20 million.

RBA And Housing – Again

Glenn Stevens in an address to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) Annual Dinner today included some further important comments on the housing sector. He was at pains to highlight what potential upcoming changes on lending standards would not be focussing on. Rather, it is an attempt “to stretch out the upswing.” In other words, the RBA still wants to use housing as part of the ongoing economic growth lever, despite high debt levels and high house prices.

As for domestic sources of demand, an obvious contributor is the set of forces at work in the housing sector. Investment in new and existing dwellings is rising. It ought to be possible, if we are being sensible both on the demand management side and the supply side, for this to go further yet and, more importantly, for the level of activity to stay high for longer than the average cyclical experience. A high level of construction, maintained for a longer period of time, is vastly preferable to a very sharp boom and bust cycle. That alternative outcome might give us a higher peak in the near term, but then a slump in the housing sector at a time when the fall in mining investment is still occurring. A sustained period of strong construction will be more helpful from the point of view of encouraging growth in non-mining activity – and also, surely, from a wider perspective: housing our growing population in an affordable manner.

Considerations such as these are among the reasons we ought to take an interest in developments in dwelling prices, the flow of credit towards housing purchases, and the prudence with which these funds are advanced. It is perhaps opportune to offer a few observations on this topic.

Having fallen in late 2010 and 2011, dwelling prices have since risen, with the median price across the country up by around $100 000 – about 18 per cent – since the low point. Prices have risen in all capitals, with a fair degree of variation: the smallest increase has been in Canberra, at about 6 per cent, and the largest in Sydney, at 28 per cent.

Credit outstanding to households in total is rising at about 6–7 per cent per year. I see no particular concern with that. When we turn to the rate of growth of credit to investors in particular, we see that it has picked up to about 10 per cent per annum over the past six months, with investors accounting for almost half of the flow of new credit.

It is not clear whether this acceleration will continue or abate. It is not clear whether price increases will continue or abate. Furthermore, it is not to be assumed that investor activity is problematic, per se. A proportion of the investor transactions are financing additions to the stock of dwellings, which is helpful. It can also be observed that a bit more of the ‘animal spirits’ evident in the housing market would be welcome in some other sectors of the economy.

Nor, let me be clear, have we seen these dynamics, thus far, as an immediate threat to financial stability. The Bank’s most recent Financial Stability Review made that clear.

So we don’t just assume that all this is a terrible problem. By the same token, after all we have seen around the world over the past decade, it is surely imprudent not to question the comfortable assumption that it is all entirely benign. A situation where:

- prices have already risen considerably in the two largest cities (where about a third of our population live)

- prices are rising, at present, faster than income by a noticeable margin, and

- an important area of credit growth has picked up to double-digit rates

should prompt a reasonable observer to ask the question whether some people might be starting to get just a little overexcited. Such an observer might want to satisfy themselves that lending standards are being maintained. And they might contemplate whether some suitably calibrated and focused action to help ensure sound standards, and that might lean into the price dynamic, may be appropriate. That is the background to the much publicised comment that the Bank was working with other agencies to see what more could be done on lending standards.

Let’s be clear what this is not about. It is not an attempt to restrain construction activity. On the contrary, it is an attempt to stretch out the upswing. Nor is it a return to widespread attempts to restrict lending via direct controls. That era, that some of us remember all too well, was one in which the price of credit was simply too low and credit growth too high all round. We don’t have that problem at present. That growth of credit to many borrowers remains moderate suggests that the overall price of credit is not too low. In fact the level of interest rates, although very low, is well warranted on macroeconomic grounds. The economy has spare capacity. Inflation is well under control and is likely to remain so over the next couple of years. In such circumstances, monetary policy should be accommodative and, on present indications, is likely to be that way for some time yet. But for accommodative monetary policy to support the economy most effectively overall, it’s helpful if pockets of potential over-exuberance don’t get too carried away.

Turning from housing investment to investment more generally, a more robust picture for capital spending outside mining would be part of a further strengthening of growth over time. Some of the key ingredients for this are in place. To date, there are some promising signs of stronger intentions, but not so much in the way of convincing evidence of actual commitment yet. That’s often the way it is at this point of the cycle. Firms wait for more evidence of stronger demand, but part of the stronger demand will come from them.

With respect to consumer demand, I should complete the picture by showing an updated version of the relevant chart from last time. In brief, not much has changed. The ratio of debt to income remains close to where it has been for some time. It’s rising a little at present because income growth is a bit below trend. Household consumption growth has picked up to a moderate pace and has actually run ahead of income over the past two years. Given that household wealth has risen strongly over that period, and interest rates are low, a modest decline in the saving rate is perhaps not surprising and indeed we think it could decline a little further in the period ahead. As I’ve argued in the past, however, we shouldn’t expect consumption to grow consistently and significantly faster than incomes like it did in the 1990s and early 2000s, given that the debt load is already substantial.

Central Bank Psychology

Andrew Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, will be speaking at the Royal College of Medicine conference on Leadership: stress and hubris. He will discuss how psychological biases can affect policy making, and how the institutional design of policy making committees at the Bank of England have been designed to counteract those effects.

In the speech, Andrew highlights four “cognitive ticks that can affect human decision making” that may be relevant for public policy making:

Preference biases – where the decision maker might put “personal objectives over societal ones, such as personal power or wealth”

Myopia biases – “people differ materially in their capacity to defer gratification” and studies suggest that people who show greater patience “outperform their impatient counterparts in everything from school examinations, to salaries, to reported life satisfaction”.

Hubris biases – over-confident individuals are “more likely to be promoted to positions of influence” but tend to pursue “over ambitious targets” like “undertaking over-complex company takeovers. That way nemesis lies”

Groupthink biases – people tend to adapt their view to confirm to those around them and also have a “tendency to search and synthesize information in ways which confirm their prior beliefs”.

Andrew then shows how policy making at the Bank of England has been organised to try to protect from these biases.

To tackle preference bias, the Bank’s does not set its own objectives. It has three policy making committees – for monetary policy (MPC), financial policy (FPC) and prudential regulation (PRA Board). In addition, “to ensure the actions of the Bank’s policy committees are well-aligned with society’s wishes” their targets are “set ex-ante in legislation by Parliament acting on behalf of society”.

To prevent myopia, the Bank of England has been made independent from government when choosing how to set monetary and financial policy to achieve their respective objectives. These decisions have been given to an institution “whose time horizon stretches beyond the political cycle”. Andrew suggests that central bank independence has been successful at taming “the inflation tiger” but he warns that “as some countries are finding today, the tiger is capable of biting back” in the form of low and falling inflation expectations. Andrew notes that while inflation expectations in the UK have held up pretty well, this is something he is “watching like a dove.”

To guard against Hubris at the Bank, “all policy decisions … are made by Committee rather than an individual” which “provides some natural safeguard against over-confidence bias”. Andrew notes that external MPC members have contributed importantly to the diversity of opinion on the committee “on average they have been around twice as likely as internals to dissent from monetary policy decisions”.

Finally to ward off groupthink, each member of the policy committees is individually accountable for their vote or view, and this should encourage “a variety of analytical perspectives”. That said Andrew notes that analysis of MPC minutes suggests that they did not devote enough time to discussing banking issues in the run up to the financial crisis, something that in hindsight, “looks like a collective analytical blind-spot”. He argues that despite all the changes to the Bank’s policy responsibilities since the crisis, “it is too soon to tell whether any remaining blind-spots remain”. Also, in his view “improvements to the Bank’s forecasting process have some considerable distance still to travel”.

Andrew concludes by highlighting a key new development at the Bank – a “cultural revolution” for bank research work. Rather than being used solely to “nourish and support the Bank’s policy thinking”, as has typically been the case in the past, future Bank research will instead be published that challenges the policy orthodoxy as often as supports it . “This research will hopefully act as spur and springboard for new policy thinking”. “It will act as another hopefully powerful, bulwark against over-confidence biases and groupthink.

The State Of House Price Movements

The RPData CoreLogic Home Value Index for October shows an average increase in prices of 1% across the capital cities. However, there are major variations. Although combined capital city home values were up by 1.0 per cent over the month, only Sydney (1.3%), Melbourne (1.9%) and Brisbane (0.6%) actually recorded value rises over the month.

Dwelling values rose by 2.2 per cent over the three months to October 2014 however, only half of the capital cities actually recorded an increase in values. The greatest value falls over the last three months were recorded in Hobart (-2.8%) and Canberra (-2.4%).

ASIC’s Annual Report Tabled

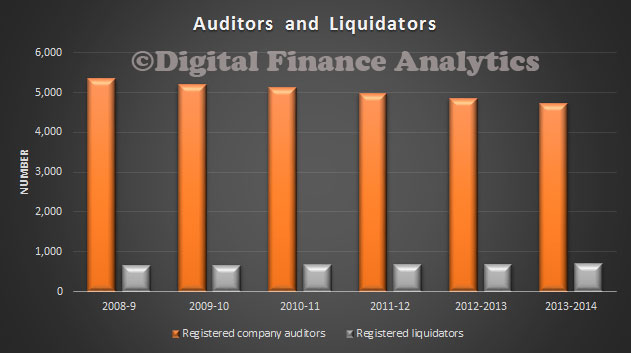

ASIC’s annual report for the 2013–14 financial year was tabled on Wednesday 29 October 2014 in the Australian Parliament. Its 185 pages highlights the broad range of issues ASIC covers, and connects back to their earlier strategy release. DFA found some interesting nuggets of information in the 6 year trends table.

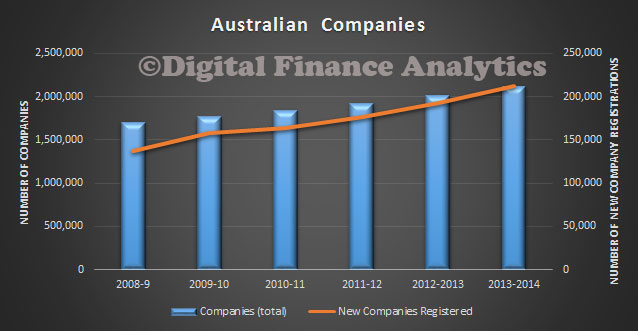

There has been a steady rise in the number of companies in Australia, with over 2.1 million operating. Last year more than 212,000 new companies were registered, whilst about 85,000 closed.

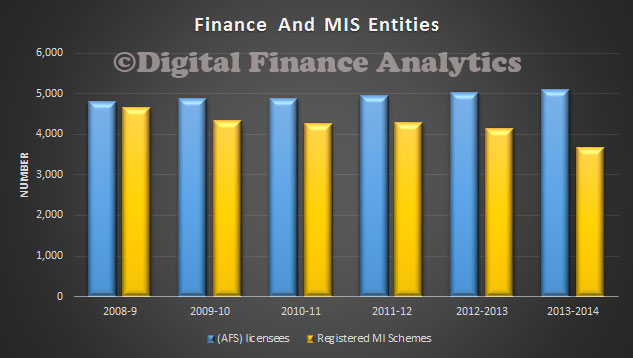

There was a steady rise in the number of Australian Financial Services Licenses issued, including a number of limited licenses to Accountants enabling them to offer financial advice. On the other hand, the number of registered Managed Investment Schemes (MIS) fell, explained partly by the collapse of agribusiness schemes such as Timbercorp and Great Southern.

There was a steady rise in the number of Australian Financial Services Licenses issued, including a number of limited licenses to Accountants enabling them to offer financial advice. On the other hand, the number of registered Managed Investment Schemes (MIS) fell, explained partly by the collapse of agribusiness schemes such as Timbercorp and Great Southern.

Finally, we note that the number of registered Auditors fell a little, now below 5,000 (despite the rise in companies), as there has been considerable consolidation in the audit sector; whilst the number of entities registered as Liquidators rose slightly.

Finally, we note that the number of registered Auditors fell a little, now below 5,000 (despite the rise in companies), as there has been considerable consolidation in the audit sector; whilst the number of entities registered as Liquidators rose slightly.

UK Bank Write-Downs Normalising

The Bank of England just released their latest datapacks. One interesting view is the loss trends reported by Banks and Building Societies.

The chart (shown by value) highlights the significant issues in credit cards amongst the UK banks in 2010/2011, and by contrast shows the value of write-offs from dwellings has been lower and more stable.

The chart (shown by value) highlights the significant issues in credit cards amongst the UK banks in 2010/2011, and by contrast shows the value of write-offs from dwellings has been lower and more stable.

Losses are more normalised now, showing the UK economy is beginning to heal. But a case study in what happens in a significant financial crisis to household write-offs, and the relative risks of secured and unsecured lending.