Apartment owners in high-rise units are realising their properties are worth less than they paid for them as rampant oversupply and falling demand send real estate values plummeting. Via RealEstate.com and The Daily Telegraph.

Recent sales figures indicated multiple unit owners made a loss on their investments, with some apartments in high rise buildings selling for up to $150,000 below what the sellers paid.

Such sales were particularly prevalent in construction hubs such as the suburbs of North Ryde and Rosehill, near Parramatta.

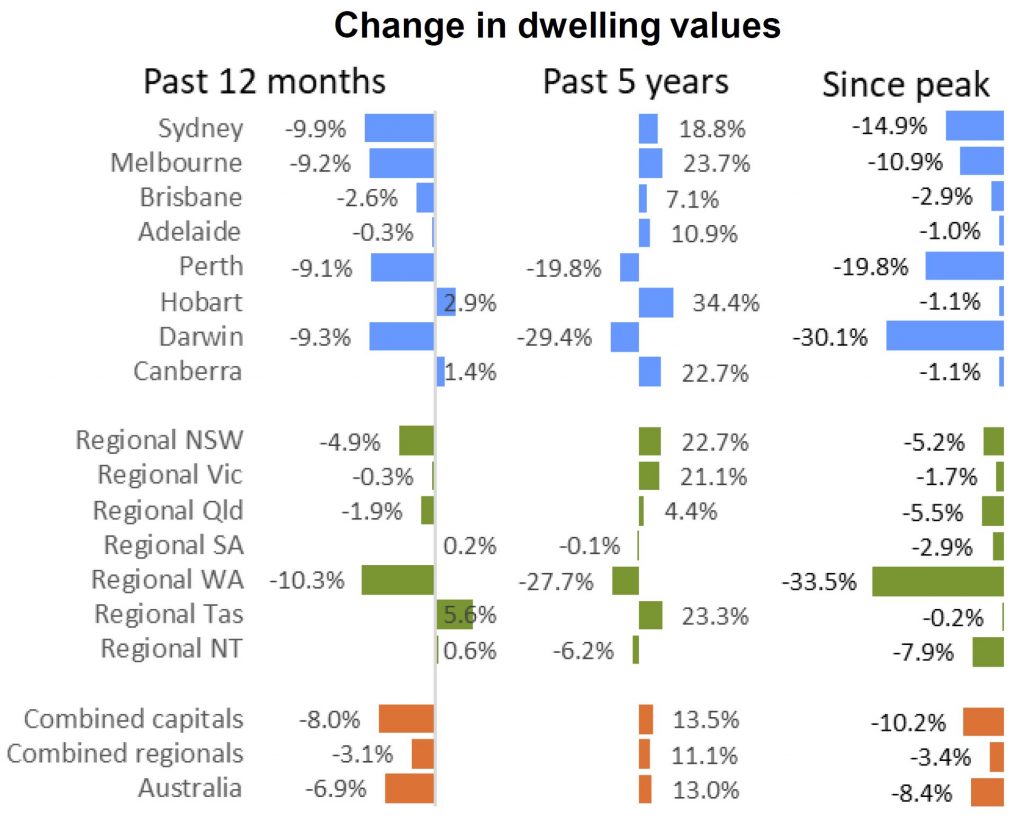

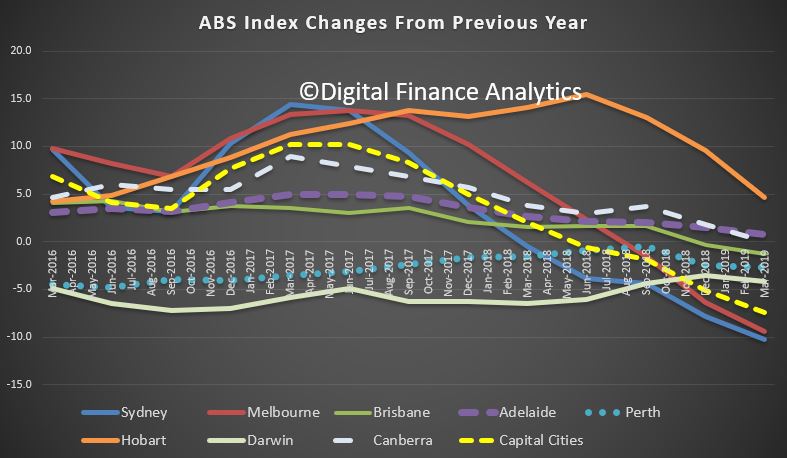

The suburbs were among the few Sydney areas where average prices have fallen below what they were in 2014, according to research from CoreLogic.

Multiple units in this complex on Allengrove Crescent in North Ryde have sold at a loss for the sellers, including one for $150K less than the vendor paid.

Median unit prices in the suburbs were 2-5 per cent cheaper than they were five years ago.

Median prices in other suburbs with a high supply of new units such as Hillsdale, in the Botany area, and inner west suburb Lewisham were below their 2016 levels, along with Zetland and Kellyville.

Suburbs with such deep drops in prices remained rare considering real estate values skyrocketed in the years between 2013 and 2017.