As Generation Y begins to enter the housing market, there could be a change in the types of dwellings sought after, a new report has suggested.

According to industry analyst and economic forecasters BIS Oxford Economics, changes to the age profile of the population over the next decade will likely result in a shift in the type of demand for dwellings, as Generation Y – those currently aged around 20 to 34 years old – begin to have their own families and move onto the property ladder.

According to BIS’s Emerging Trends in Residential Market Demand report, which examines trends revealed by a detailed analysis of Census data from the past 25 years, there will be “solid demand for units and apartments over the next decade” driven by an overall increase in “the propensity to be living in higher density dwellings across all age groups”.

The report outlines that while there will be continued demand for units and apartments over the next decade, the growth in demand will eventually slow.

Senior manager for residential property at BIS Oxford Economics, Angie Zigomanis, has suggested that, over the past 15 years, there has been rapid population growth among 20-to 34-year olds, as well as strong net overseas migration inflows, which have helped support the boom in apartment construction in the past decade by supplying a steady stream of new tenants to the market.

Mr Zigomanis also noted that there is evidence that people are staying in apartments and townhouses longer.

The analyst highlighted that, in Sydney, more than half (53 per cent) of households aged 35-to 39-years old, and nearly half (49 per cent) of households with children at a pre-school age, now live in these smaller dwellings.

While households have typically favoured townhouses over apartments, in Sydney and Melbourne, there has been an acceleration in the take-up of apartments by both groups since the 2011 Census. The trend has also been similar, although less pronounced in Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, the report added.

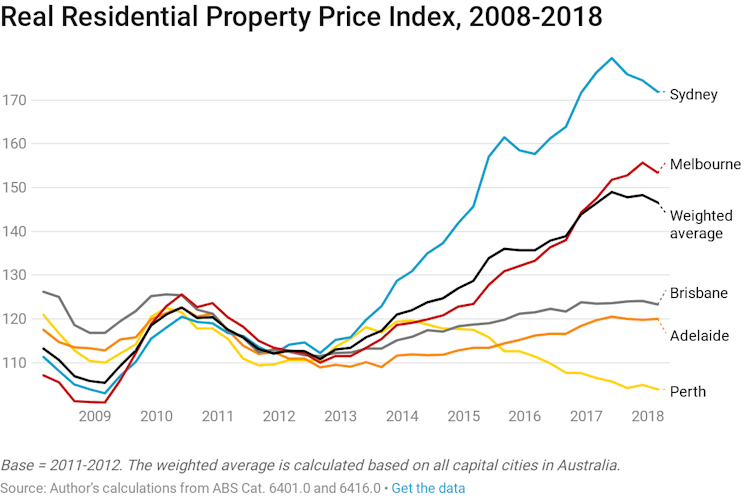

Looking to the future, BIS notes that rising demand for smaller dwellings by Generation Y over the next decade would be apparent across all capital cities, although will be most pronounced in Sydney, and to a lesser extent Melbourne, where separate houses are least affordable.

In Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, it argued, householders would be much more likely to be in a detached house once they enter their late 30s and 40s, and strong demand for new separate houses is therefore likely to continue.

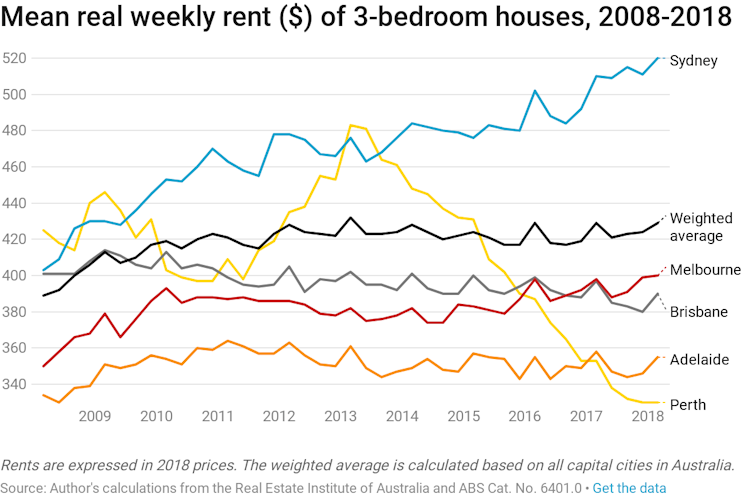

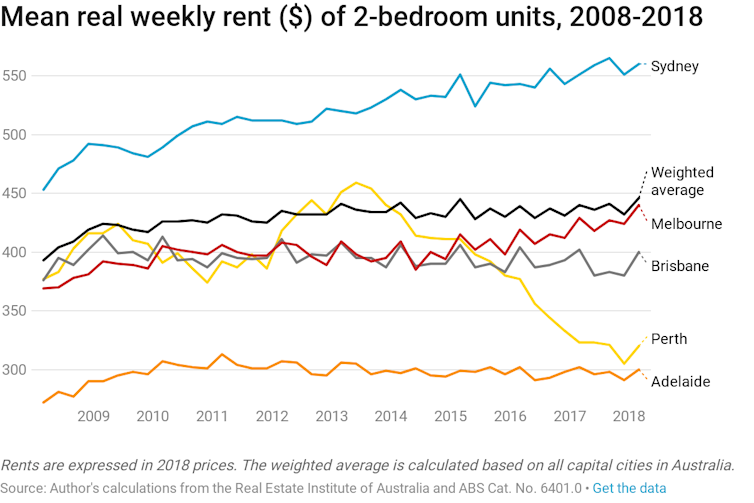

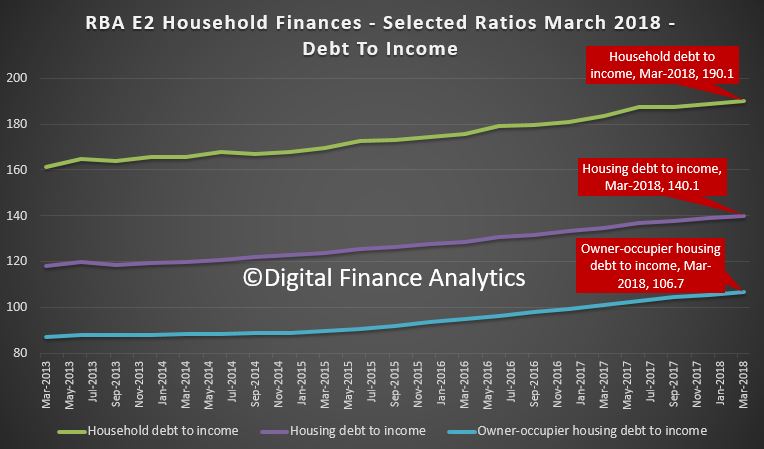

However, BIS argues that it is likely that rising house prices and decreasing housing affordability in the most desirable locations in the capital cities are causing “an increasing trade-off” for some couples and family buyers between price, size of dwelling, and location, with many seeking smaller and more affordable dwellings to remain close to their desired location.

The analysts argued that, should this trade-off activity increase as Generation Y gets older, then this provides an opportunity for developers in all capital cities to meet this demand, especially given the fact that the boom in multi-unit dwelling construction has up until now been investment-driven “with design being geared toward Generation Y renters living as singles, couples without children, and in share households,” BIS said.

“To meet the potential growing number of Generation Y families in established areas, multi-unit dwellings will need to be designed to be more appropriate to family life, offering more space, both indoor and some outdoor, or located adjacent to public outdoor spaces,” said Mr Zigomanis.

“In particular, new apartment designs will need to change to provide more appropriate product for Generation Y families.”

However, should Generation Y follow the trend of the previous generations and eschew renting for owning their own, larger dwellings as they age, then this would “support a decade-long boom in demand for new houses and land in the new housing estates on the outskirts of Australia’s major cities and affordable major regional centres,” said Mr Zigomanis.

“Pressure is also likely to be maintained on house prices in established areas, as competition remains strong for Generation Y families looking to remain in the established areas where they have already been living and renting in smaller apartments,” he said.