Welcome to the Property Imperative Weekly to 14 April 2018. We review the latest property and finance news.

There is a massive amount to cover in this week’s review of property and finance news, so we will dive straight in.

There is a massive amount to cover in this week’s review of property and finance news, so we will dive straight in.

CoreLogic says that final auction results for last week showed that 1,839 residential homes were taken to auction with a 62.8 per cent final auction clearance rate, down from 64.8 per cent over the previous week. Auction volumes rose across Melbourne with 723 auctions held and 68.2 per cent selling. There were a total of 795 Sydney auctions last week, but the higher volumes saw the final clearance rate weaken with 62.9 per cent of auctions successful, down on the 67.9 per cent the week prior. All of the remaining auction markets saw a rise in activity last week; clearance rates however returned varied results week-on-week, with Adelaide Brisbane and Perth showing an improvement across the higher volumes while Canberra and Tasmania both recorded lower clearance rates. Across the non-capital city regions, the highest clearance rate was recorded across the Hunter region, with 72.5 per cent of the 45 auctions successful.

This week, CoreLogic is currently tracking 1,690 capital city auctions and as usual, Melbourne and Sydney are the two busiest capital city auction markets, with 795 and 678 homes scheduled to go to auction. Auction activity is expected to be lower week-on week across each of the smaller auction markets

Two points to make. First is a slowing market, more homes will be sold privately, rather than via auctions, and this is clearly happening now, and second, we discussed in detail the vagaries of the auction clearance reporting in our separate blog, so check that out if you want to understand more about how reliable these figures are.

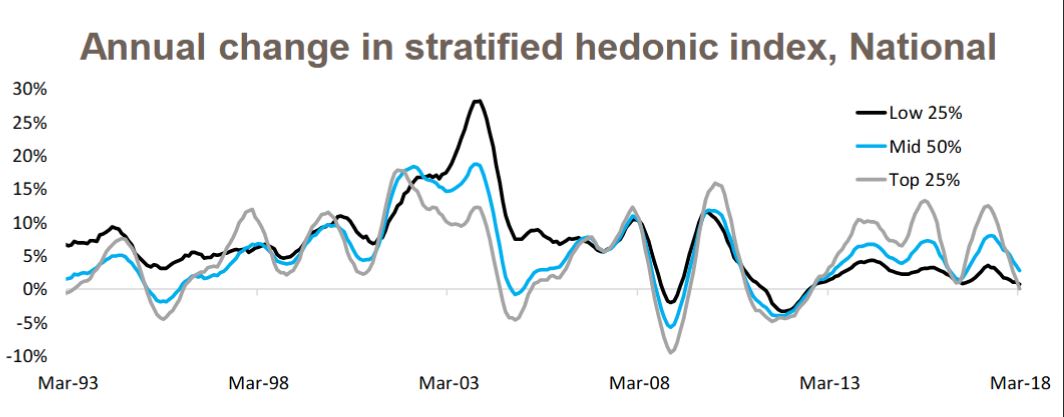

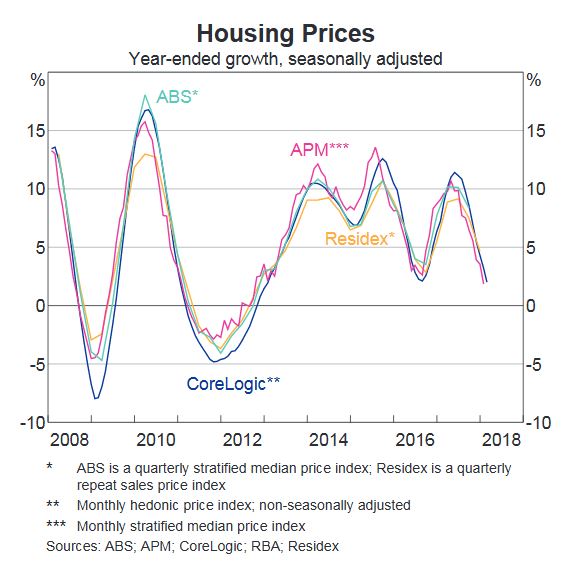

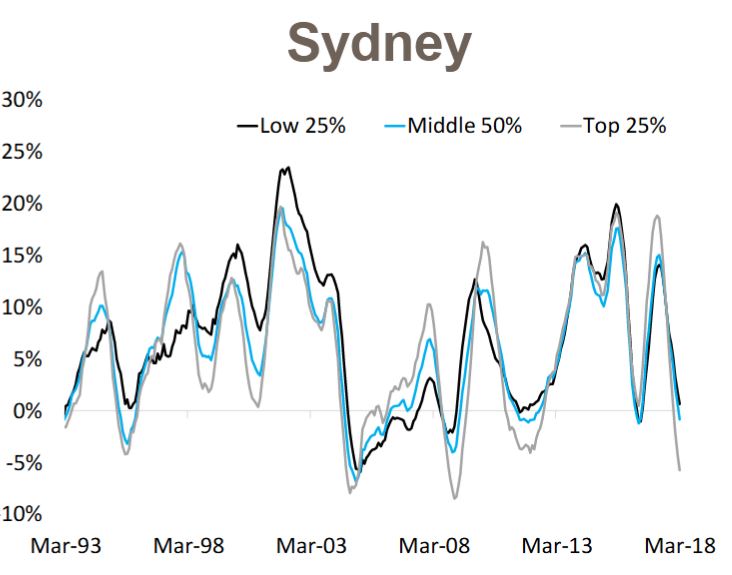

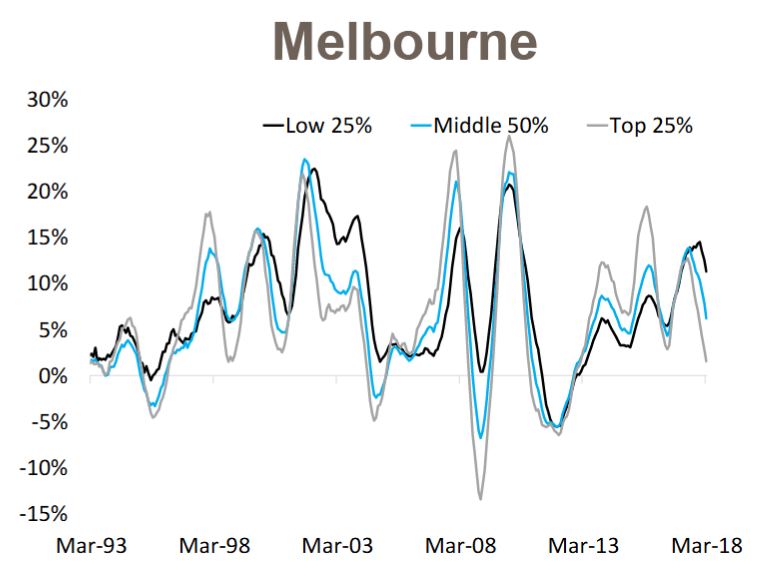

Home prices slipped a little this past week according to the CoreLogic index, but their analysis also confirmed what we are seeing, namely that more expensive properties are falling the most. In fact, values in the most expensive 25% of the property market are falling the fastest, whereas values for the most affordable 25% have actually risen in value.

Their analysis shows that over the March 2018 quarter, national data shows that dwelling values were down by 0.5%, however digging below the surface reveals the modest fall in values was confined to the most expensive quarter of the market. The most affordable properties increased in value by +0.7% compared to a +0.3% increase across the middle market and a -1.1% decline across the most expensive properties.

But looking at the details by location, in Sydney, over the past 12 months, the most expensive properties have recorded the largest value falls (-5.7%) followed by the middle market (-0.9%) and the most affordable market managed some moderate growth (+0.6%).

Compare that with Melbourne where values have increased over the past year across each segment of the market, with the most moderate increases recorded across the most expensive segment (+1.6%), then the middle 50% (+6.2%) while the most affordable suburbs have recorded double-digit growth (+11.3%)

Compare that with Melbourne where values have increased over the past year across each segment of the market, with the most moderate increases recorded across the most expensive segment (+1.6%), then the middle 50% (+6.2%) while the most affordable suburbs have recorded double-digit growth (+11.3%)

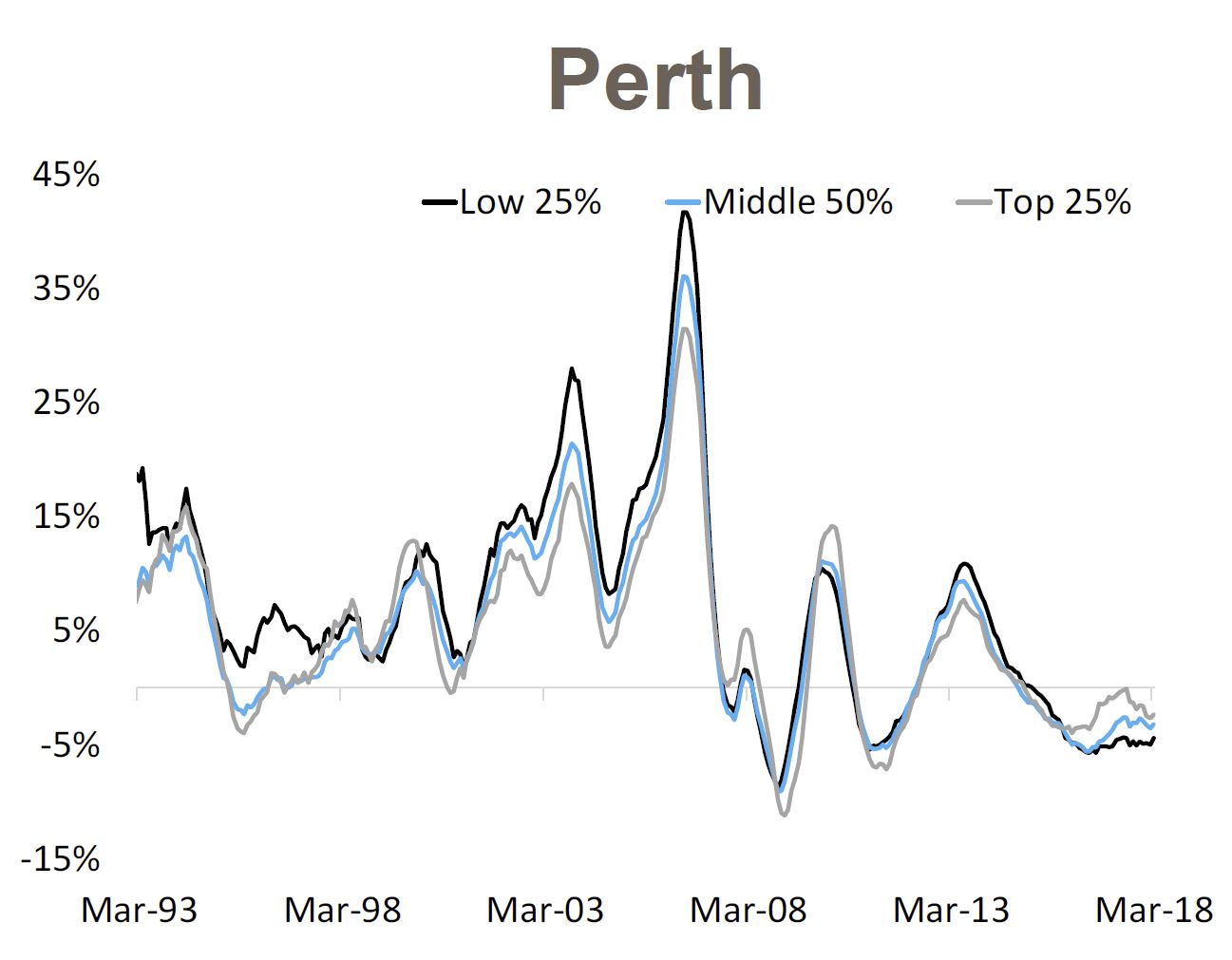

Finally, in Perth values have fallen over the past year across each market sector with the largest declines across the most affordable properties (-4.4%) followed by the middle market (-3.2%) with the most expensive properties recording the most moderate value falls (-2.4%).

Finally, in Perth values have fallen over the past year across each market sector with the largest declines across the most affordable properties (-4.4%) followed by the middle market (-3.2%) with the most expensive properties recording the most moderate value falls (-2.4%).

This shows the importance of granular information, and how misleading overall averages can be.

This shows the importance of granular information, and how misleading overall averages can be.

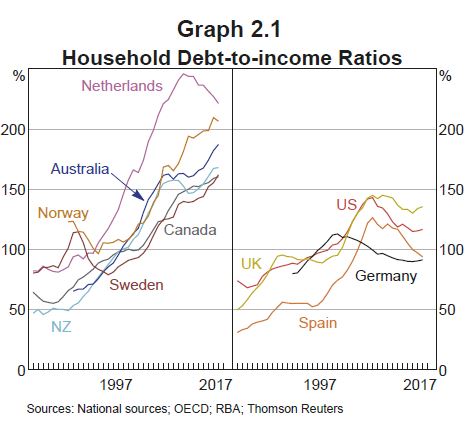

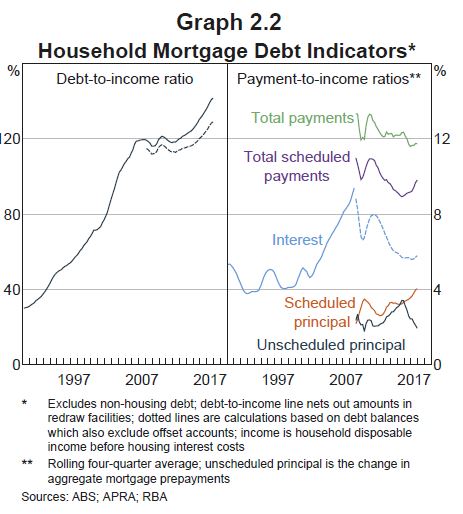

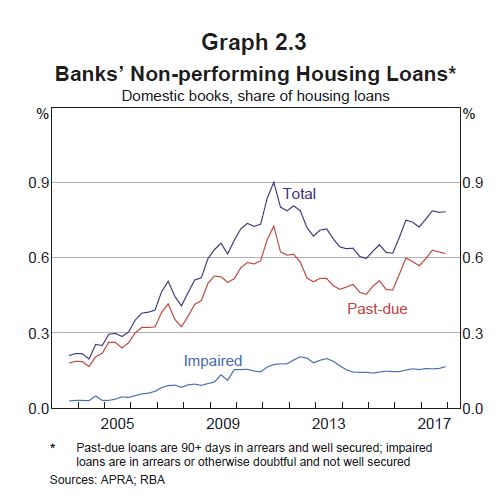

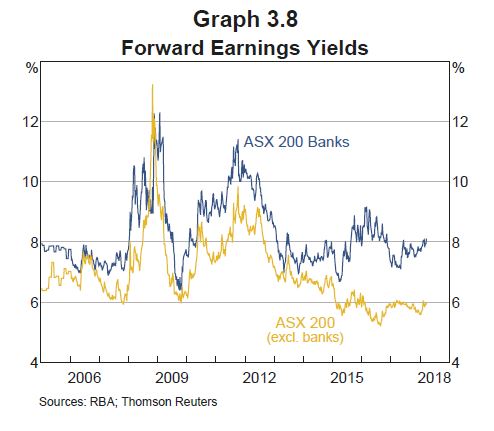

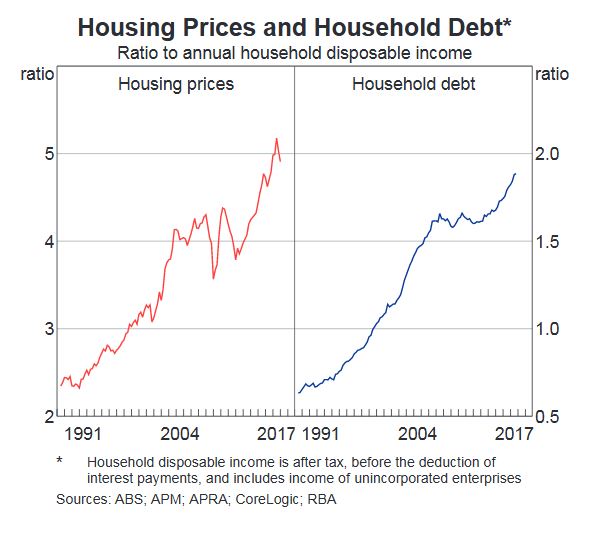

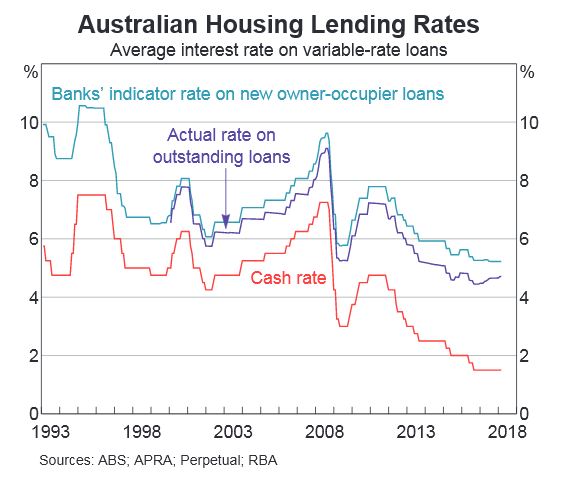

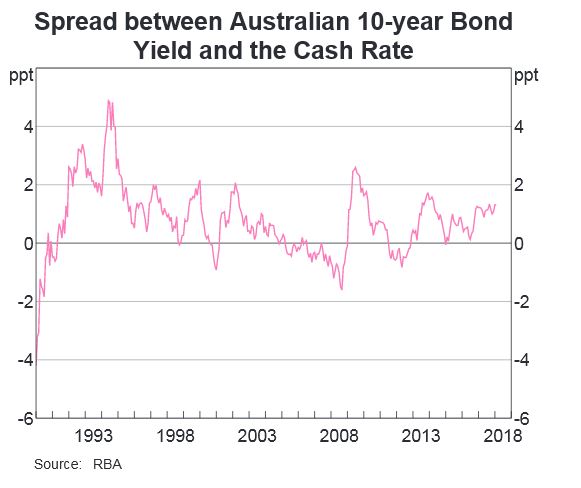

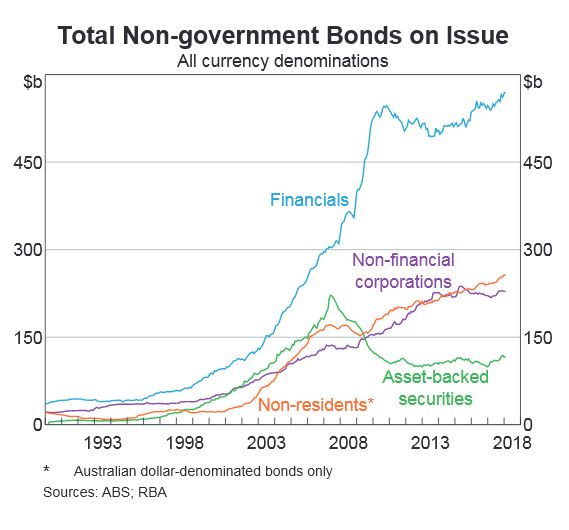

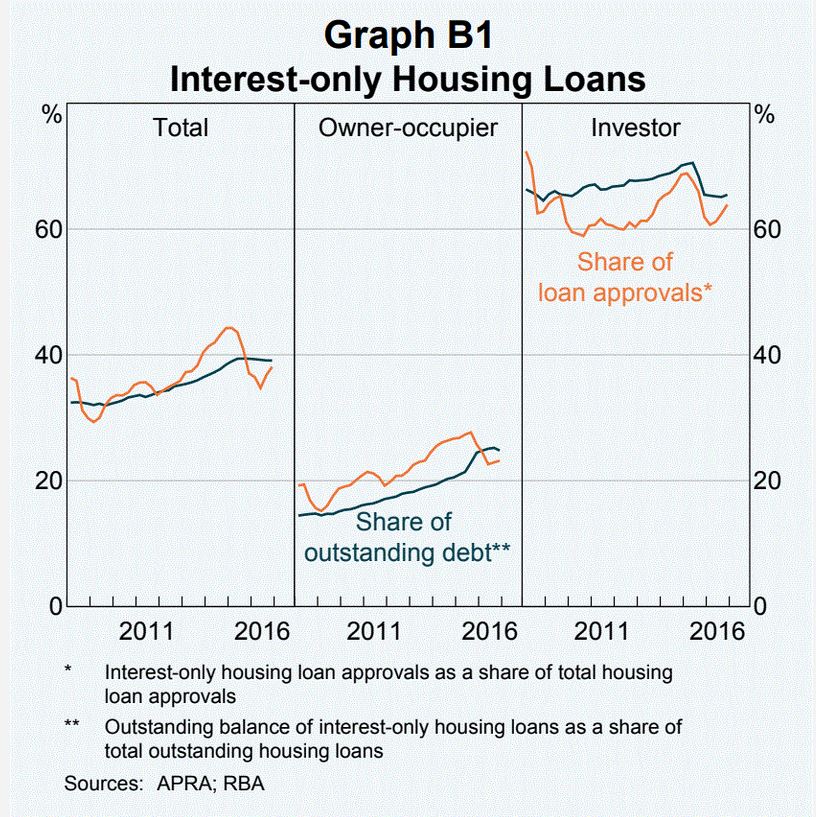

The RBA has released their Financial Stability Review today. It is worth reading the 70 odd pages as it gives a comprehensive picture of the current state of play, though through the Central Bank’s rose-tinted spectacles! They do talk about the risks of high household debt, and warn of the impact of rising interest rates ahead. They home in on the say $480 billion interest only mortgage loans due for reset over the over the next four years, which is around 30 per cent of outstanding loans. Resets to principal and interest will lift repayments by at least 30%. Some borrowers will be forced to sell.

This scenario mirrors the roll over of adjustable rate home loans in the United States which triggered the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis. Perhaps this is our own version! We have previously estimated more than $100 billion in these loans would now fail current tighter underwriting standards.

This scenario mirrors the roll over of adjustable rate home loans in the United States which triggered the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis. Perhaps this is our own version! We have previously estimated more than $100 billion in these loans would now fail current tighter underwriting standards.

I published a more comprehensive review of the Financial Stability Review, and you can watch the video on this report. Importantly the RBA suggests that banks broke the rules in their lending on interest only loans before changes were made to regulation in 2014. The RBA says that there is the potential that these will result in banks having to set aside provisions and/or face penalties for past misconduct or perhaps (more notably) being constrained in the operation of parts of their businesses.

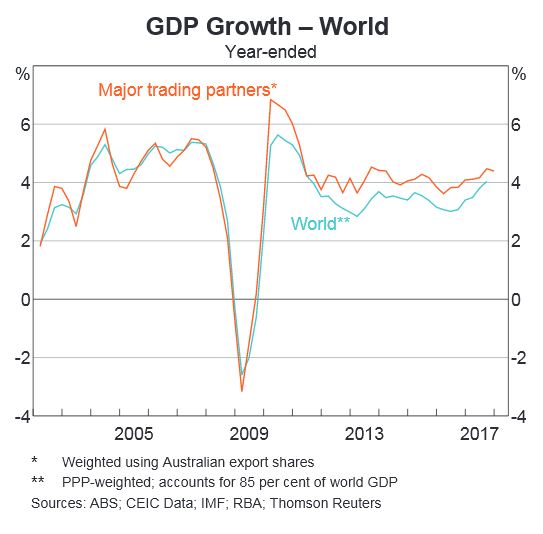

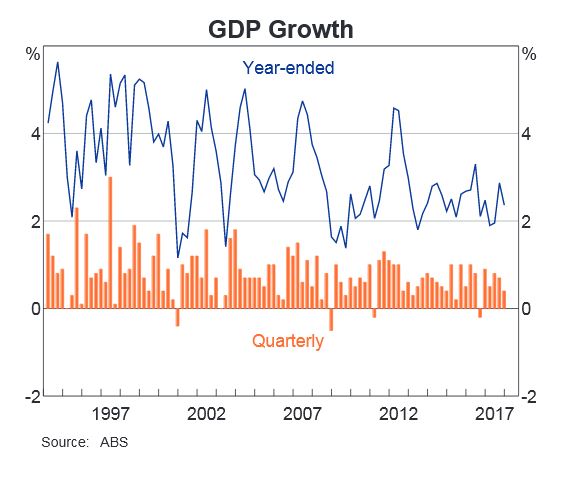

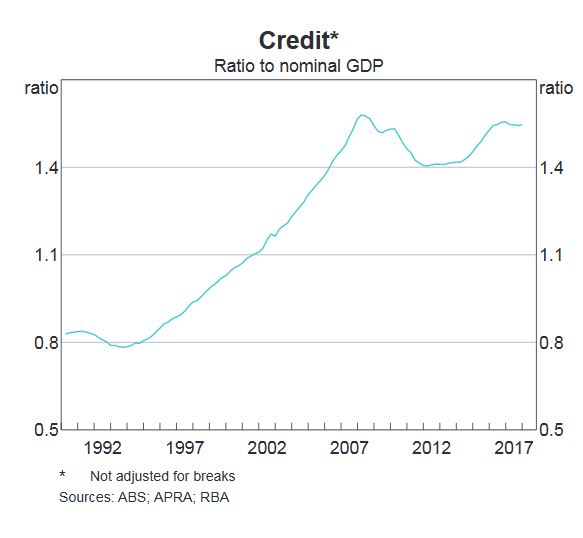

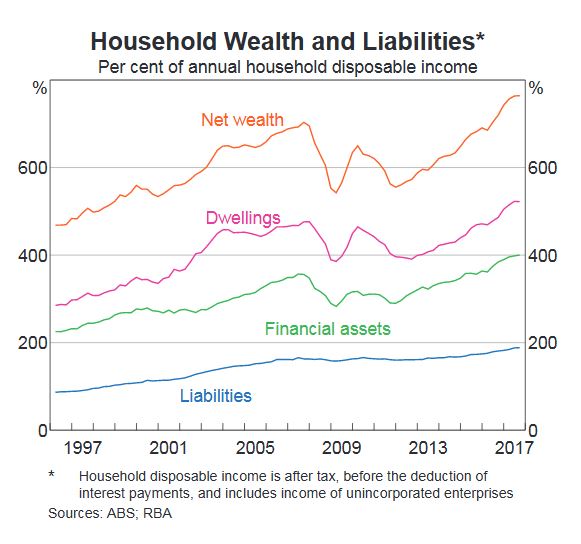

We also did a video on the RBA Chart pack which was released recently. Household consumption is still higher than disposable income, and the gap is being filled by the falling savings ratio. So, we are still spending, but raiding our savings to do so. Which of course is not sustainable. Now the other route to fund consumption is debt, so there should be no surprise to see that total household debt rose again (note this is adjusted thanks to changes in the ABS data relating to superannuation, we have previously breached the 200% mark). But on the same chart we see home prices are now falling – already the biggest fall since the GFC in 2007.

We see all the signs of issues ahead, with household debt still rising, household consumption relying on debt and savings, and overall growth still over reliant on the poor old household sector. We need a proper plan B, where investment is channelled into productive growth investments, not just more housing loans. Yet regulators and government appear to rely on this sector to make the numbers work – but it is, in my view, lipstick on a pig!

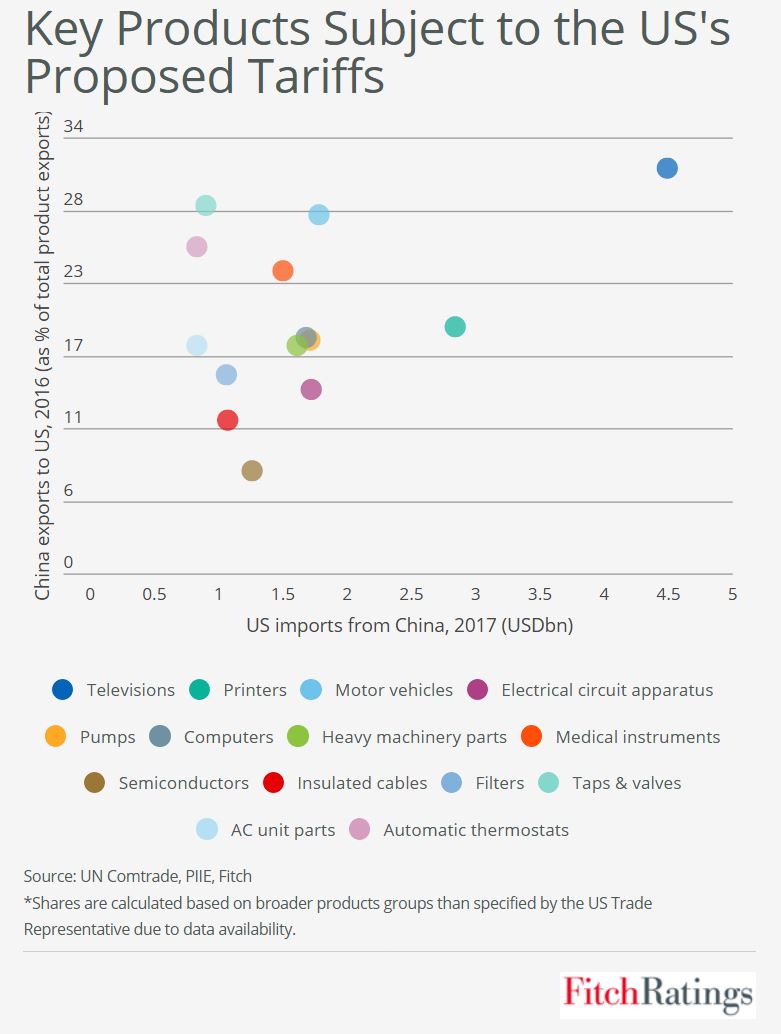

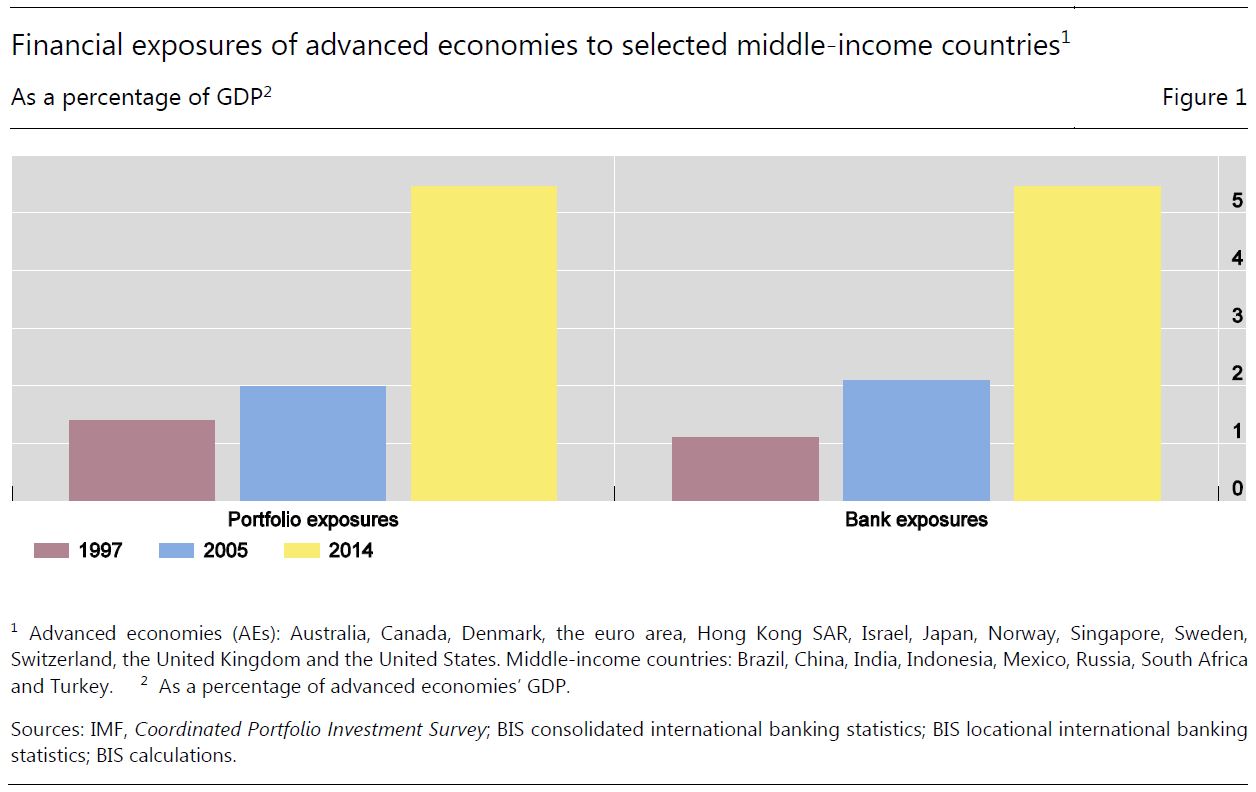

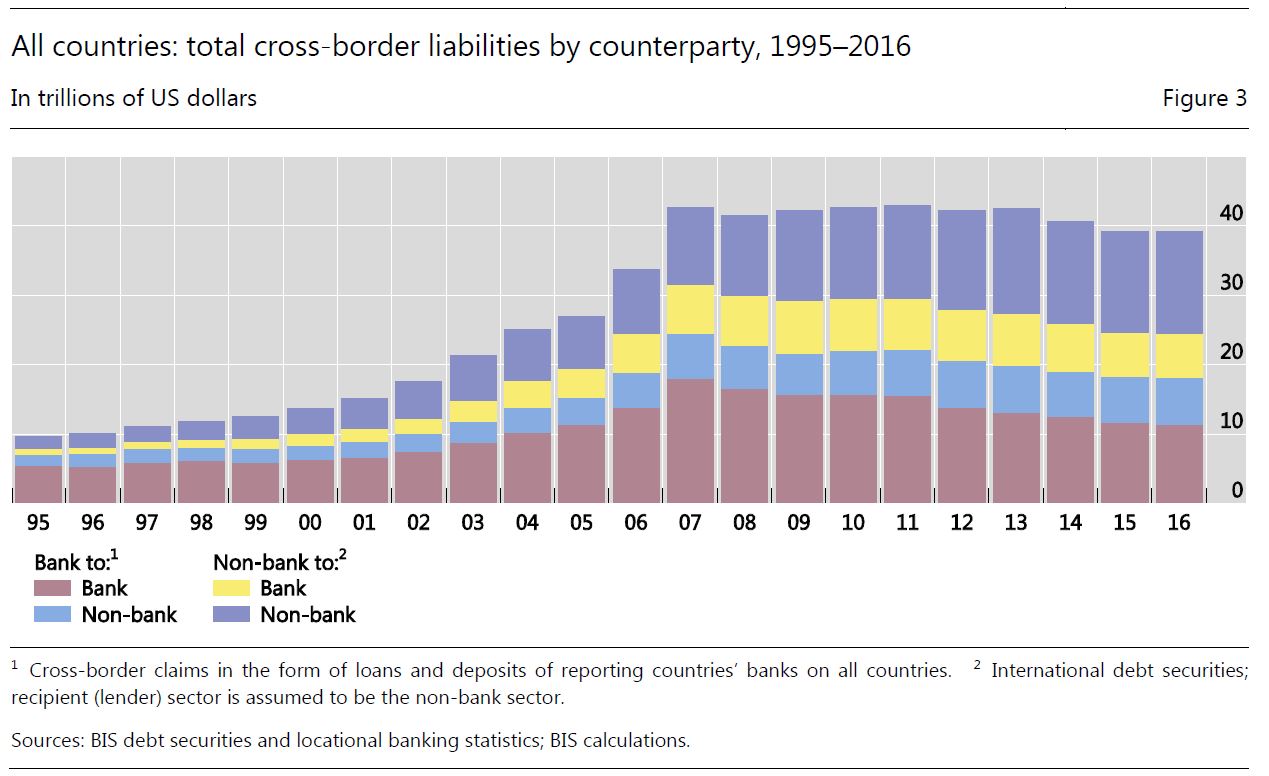

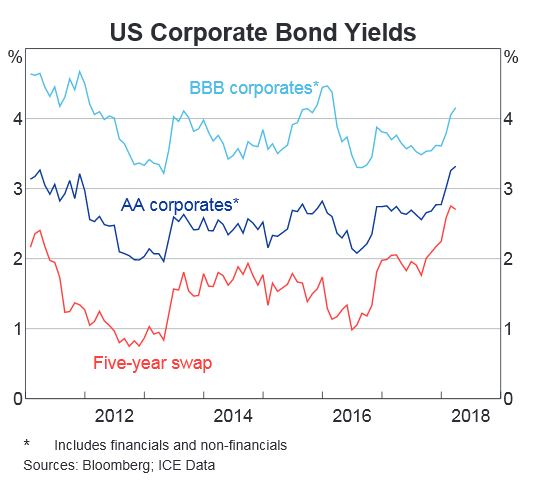

Another important report came out from The Bank for International Settlements, the “Central Bankers Banker” has just released an interesting, and concerning report with the catchy title of “Financial spillovers, spillbacks, and the scope for international macroprudential policy coordination“. But in its 53 pages of “dry banker speak” there are some important facts which shows just how much of the global financial system is now interconnected. They start by making the point that over the past three decades, and despite a slowdown coinciding with the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007–09, the degree of international financial integration has increased relentlessly. In fact the rapid pace of financial globalisation over the past decades has also been reflected in an over sixfold increase in the external assets and liabilities of nations as a share of GDP – despite a marked slowdown in the growth of cross-border positions in the immediate aftermath of the GFC. My own take is that we have been sleepwalking into a scenario where large capital flows and international financial players operating cross borders, negating the effectiveness of local macroeconomic measures, to their own ends. This new world is one where large global players end up with more power to influence outcomes than governments. No wonder that they often march in step, in terms of seeking outcomes which benefit the financial system machine. You can watch our separate video discussion on this report. Somewhere along the road, we have lost the plot, but unless radical changes are made, the Genie cannot be put back into the bottle. This should concern us all.

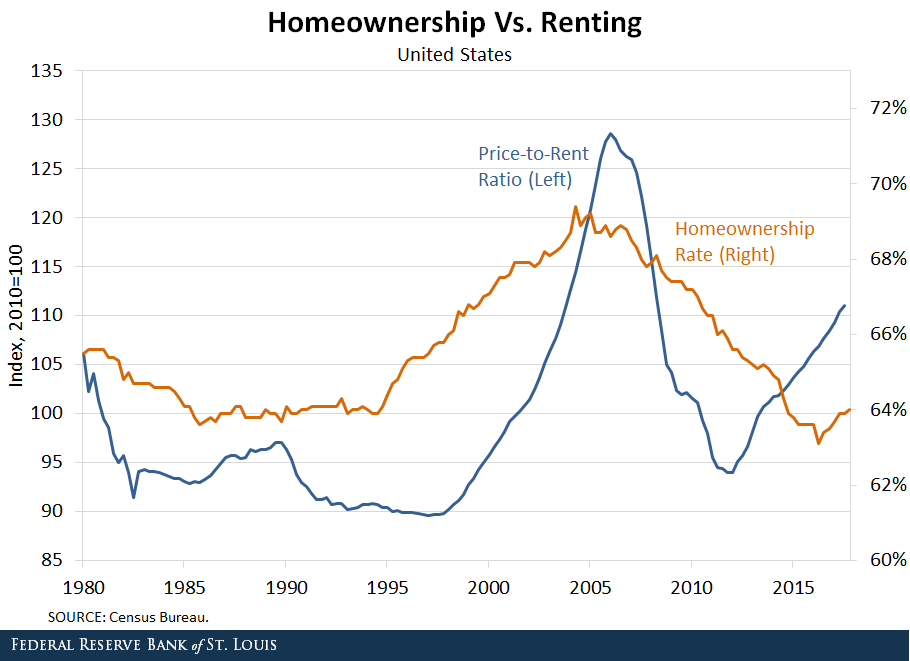

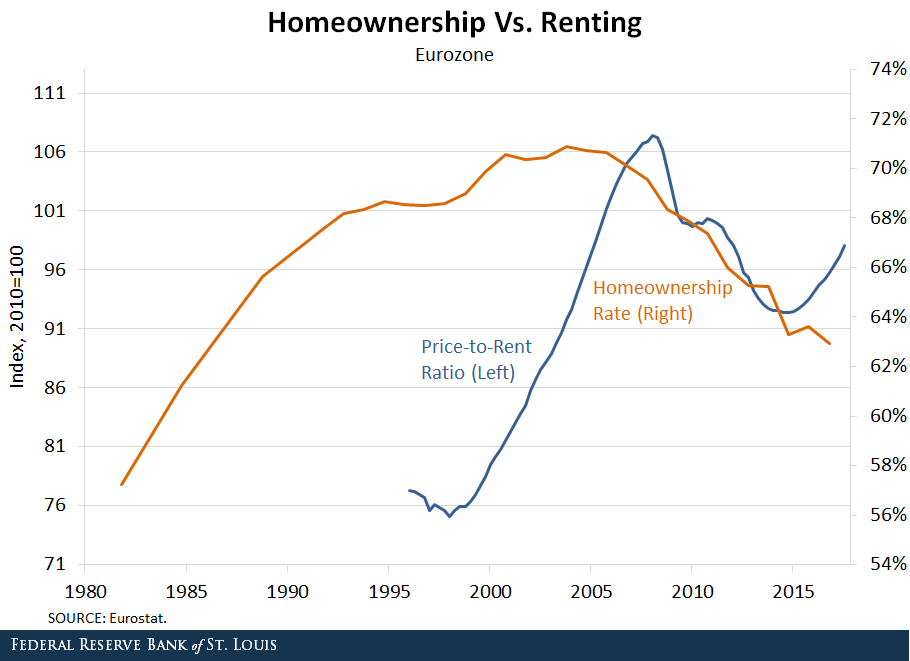

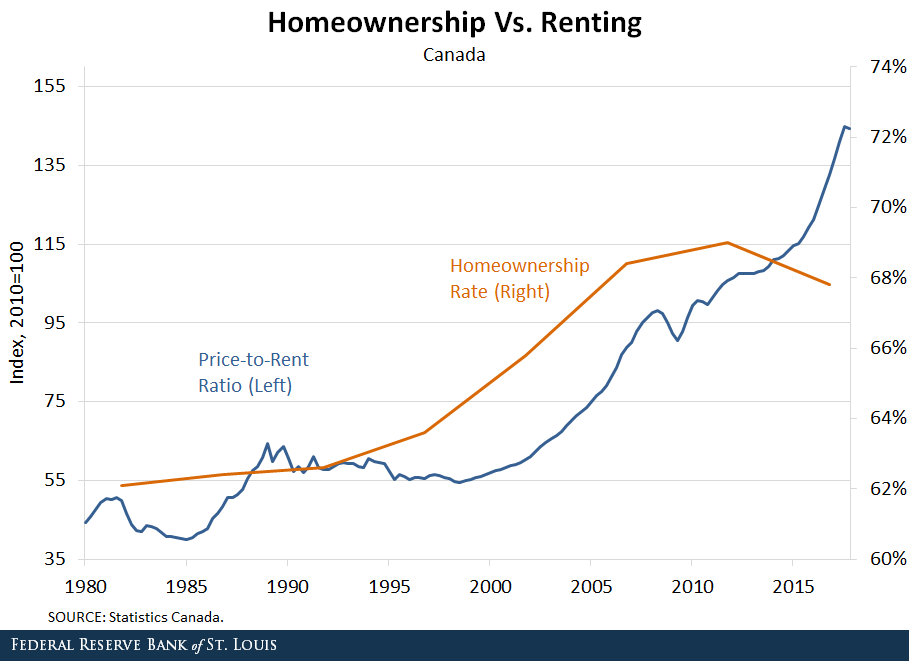

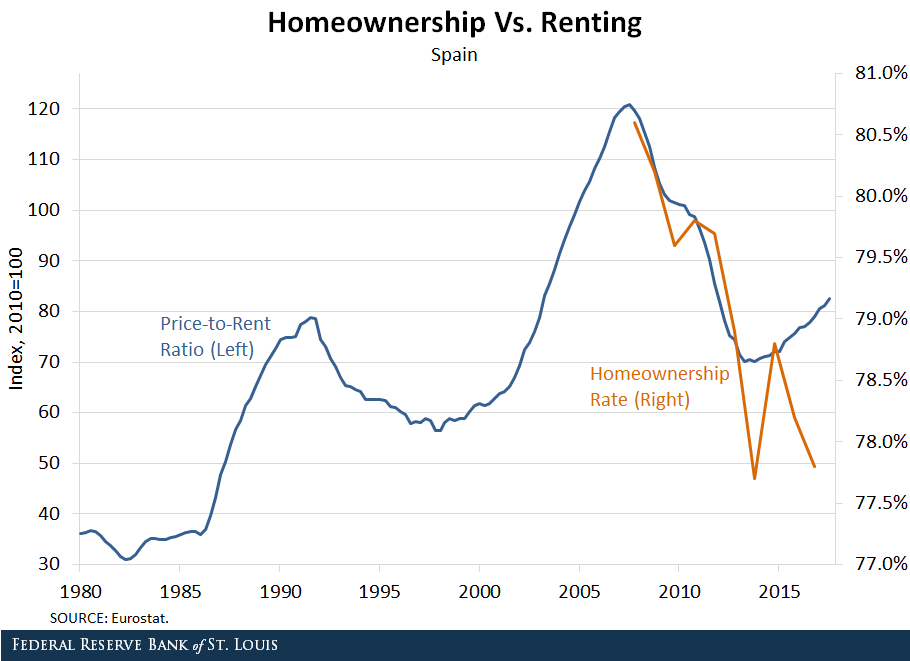

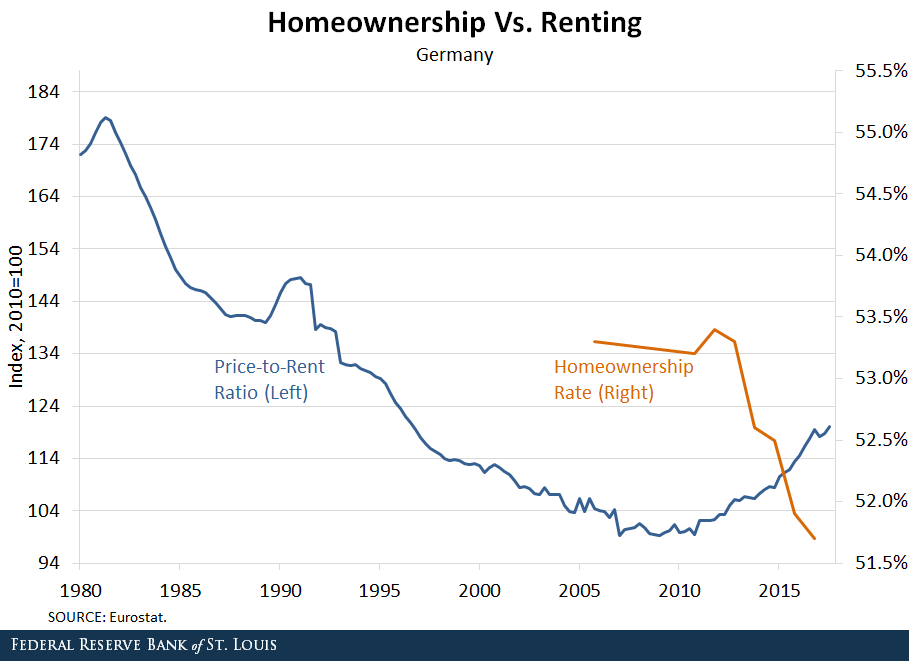

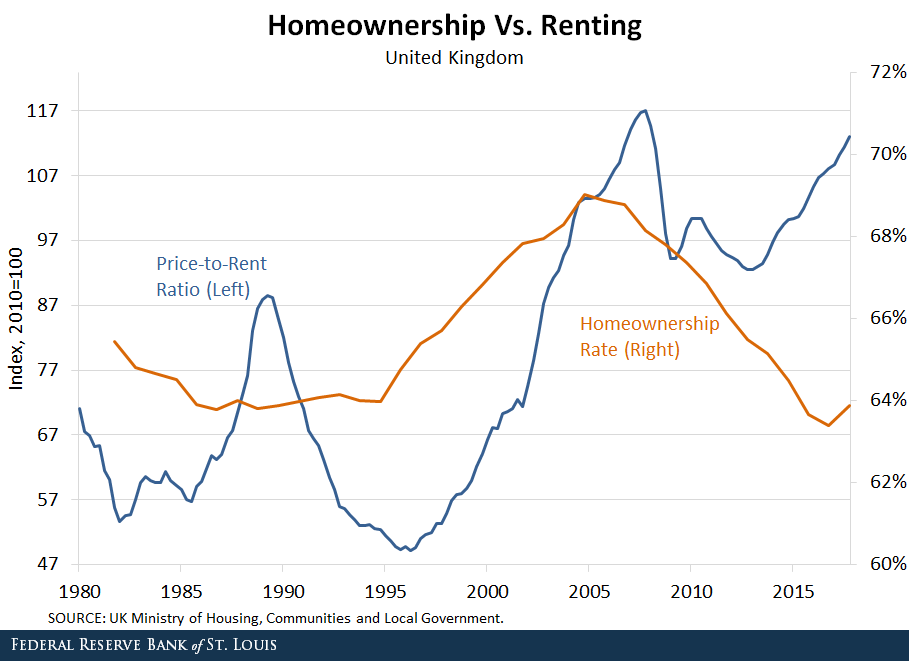

And there was further evidence of the global connections in a piece from From The St. Louis Fed On The Economy Blog which discussed the decoupling of home ownership from home price rises. They say recent evidence indicates that the cost of buying a home has increased relative to renting in several of the world’s largest economies, but the share of people owning homes has decreased. This pattern is occurring even in countries with diverging interest rate policies. And the causes need to be identified. We think the answer is simple: the financialisation of property and the availability of credit at low rates explains the phenomenon.

And finally on the global economy, Vice-President of the Deutsche Bundesbank Prof. Claudia Buch spoke on “Have the main advanced economies become more resilient to real and financial shocks? and makes three telling points. First, favourable economic prospects may lead to an underestimation of risks to financial stability. Second resilience should be assessed against the ability of the financial system to deal with unexpected events. Third there is the risk of a roll back of reforms. The warning is clear, we are not prepared for the unexpected, and as we have been showing, the risks are rising.

Locally more bad bank behaviour surfaced this week. ASIC says it accepted an enforceable undertaking from Commonwealth Financial Planning Limited and BW Financial Advice Limited, both wholly owned subsidiaries of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). ASIC found that CFPL and BWFA failed to provide, or failed to locate evidence regarding the provision of, annual reviews to approximately 31,500 ‘Ongoing Service’ customers in the period from July 2007 to June 2015 (for CFPL) and from November 2010 to June 2015 (for BWFA). They will pay a community benefit payment of $3 million in total. Cheap at half the price!

In similar vein, ASIC says it has accepted an enforceable undertaking from Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) after an investigation found that ANZ had failed to provide documented annual reviews to more than 10,000 ‘Prime Access’ customers in the period from 2006 to 2013. Again, they will pay a community benefit payment of $3 million in total.

Both these cases were where the banks took fees for services they did not deliver – and this once again highlight the cultural issues within the banks, were profit overrides good customer outcomes. We suspect we will hear more about poor cultural norms this coming week as the Royal Commission hearing recommence with a focus on financial planning and wealth management.

Finally to home lending. The ABS released their February 2018 housing finance data. Where possible we track the trend data series, as it irons out some of the bumps along the way. The bottom line is investor as still active but at a slower rate. Some are suggesting there is evidence of stabilisation, but we do not see that in our surveys. Owner occupied loans, especially refinancing is growing quite fast – as lenders seek out lower risk refinance customers with attractive rates. First time buyers remain active, but comprise a small proportion of new loans as the effect of first owner grants pass, and lending standards tighten. You can watch our video on this.

But the final nail in the coffin was the announcement from Westpac of significantly tighten lending standards, with a forensic focus on household expenditure. They have updated their credit policies so borrower expenses will need to be captured at an “itemised and granular level” across 13 different categories and include expenses that will continue after settlement as well as debts with other institutions. They will also be insisting on documentary proof. Moreover, households will be required to certify their income and expenses is true. This cuts to the heart of the liar loans issue, as laid bare in the Royal Commission. That said, Despite the commission raising questions over whether the use of benchmarks is appropriate when assessing the suitability of a loan for a customer, the Westpac Group changes will still apply either the higher of the customer-declared expenses or the Household Expenditure Measure (HEM) for serviceability purposes. You can watch our separate video on this. Almost certainly other banks will follow and tighten their verification processes. This will put more downward pressure on lending multiples, and will lead to a drop in credit, with a follow on to put downward pressure on home prices.

We discussed this in an article which was published under my by-line in the Australian this week, where we argued that excess credit has caused the home price bubble, and as credit is reversed, home prices will fall.

Our central case is for a fall on average of 15-20% by the end of 2019, assuming no major international incidents. The outlook remains firmly on the downside in our view.