Rod Sims, Chairman ACCC spoke at the AFR Banking and Wealth Summit “Synchronised swimming versus competition in banking”. His excellent speech is worth reading in full. Net, net, the tempo for reform just got stronger still….

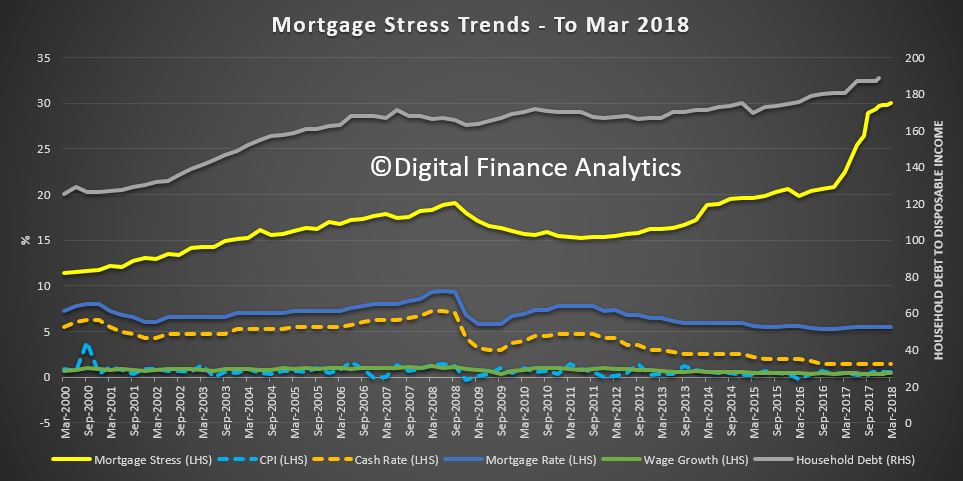

He discussed the results of their recent investigation into mortgage pricing, and also discussed the broader issues of competition versus financial stability in banking. He warns that the industry should be aware of, and respond to, the fact that the drive for consumers to get a better deal out of banking is shared by many beyond the ACCC. Every household in Australia is watching.

He discussed the results of their recent investigation into mortgage pricing, and also discussed the broader issues of competition versus financial stability in banking. He warns that the industry should be aware of, and respond to, the fact that the drive for consumers to get a better deal out of banking is shared by many beyond the ACCC. Every household in Australia is watching.

He specifically called out a lack of vigorous mortgage price competition between the five big Banks, hence “synchronised swimming”. Indeed, he says discounting is not synonymous with vigorous price competition. They saw evidence of communications “referring to the need to avoid disrupting mutually beneficial pricing outcomes”.

He also said residential mortgages and personal banking more generally make one of the strongest cases for data portability and data access by customers to overcome the inertia of changing lenders.

Finally, on competition. he says if we continue to insulate our major banks from the consequences of their poor decisions, we risk stifling the cultural change many say is needed within our major banks to put the needs of their customers first. Vigorous competition is a powerful mechanism for driving improved efficiency, and also for driving improved price and service offerings to customers. It can in fact lead to better stability outcomes.

This puts the ACCC at odds with APRA who recent again stated their preference for financial stability over competition – yet in fact these two elements are not necessarily polar opposites!

As the economy-wide competition and consumer regulator, the ACCC has always had a role in the banking sector. It is fair to say, however, that our role has been reactive to date, focusing on pursuing breaches of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010.

For example, following an ACCC investigation the Federal Court, 16 months ago, imposed a penalty of $9 million against ANZ and $6 million against Macquarie for attempted cartel conduct.

We’ve also always had a role in considering mergers in the banking sector.

But following the Treasurer’s 2017/18 Budget announcement, the ACCC now has a proactive role in the financial services sector. We have established a permanent team within the ACCC, the Financial Services Unit (FSU), to investigate competition in our banking and financial system.

The FSU was originally a recommendation of the Coleman Committee Review of the Four Major Banks in November 20161, which said:

… the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission… [should] establish a small team to make recommendations to the Treasurer every six months to improve competition in the banking sector.

If the relevant body does not have any recommendations in a given period, it should explain why it believes that no changes to current policy settings are required.

The FSU will undertake regular inquiries into specific financial service competition issues, and so facilitate greater competition in the sector.

The first task of the FSU is the current Residential Mortgage Price Inquiry; the interim report was released on 15 March.

In addition, the Government has recently announced that the ACCC will be the lead regulator for the consumer data right, with banking being the first sector covered.

Clearly our role in the financial sector will be more active than it has been in the past.

Today I will cover three topics.

- The findings from the interim report from our Residential Mortgage Price Inquiry

- Data as a competition driver, and

- Stability and competition; the topic we avoid but must talk about.

1. Residential mortgage price inquiry findings

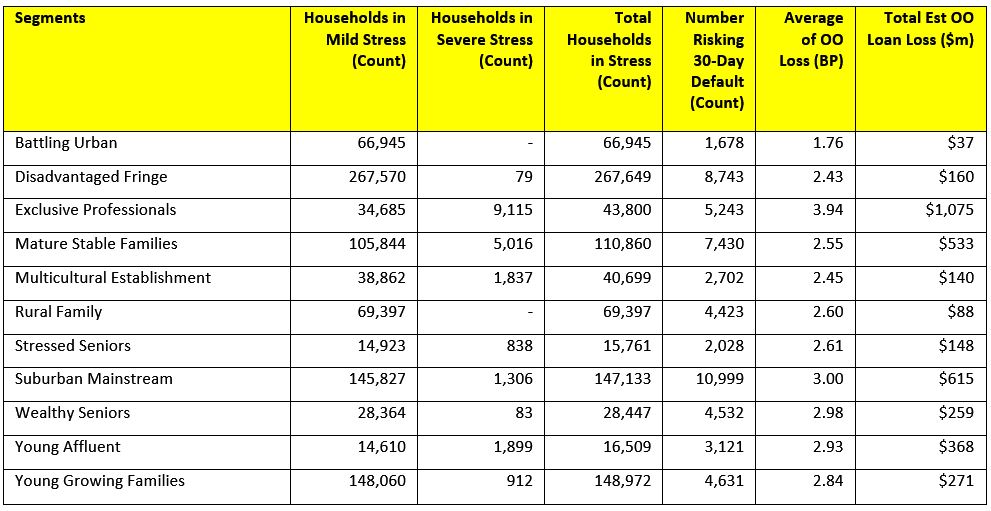

Our interim report indicates quite clearly, based on evidence we have collected, that not only does competition in the banking sector need to improve, but that where there appears to be competition it may often be illusory.

A number of issues were raised in the interim report; today I will concentrate on three:

- The transparency of interest rates

- The treatment of loyal customers compared to new customers

- Why discounts do not indicate vigorous competition.

The transparency of rates: apples and oranges

It is the nature of competition that similar goods can be compared; you need to be able to compare apples with apples.

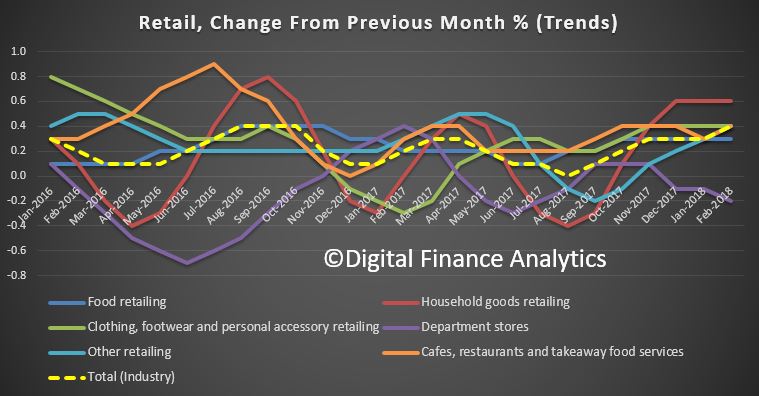

It is the nature of residential mortgage products, however, that no two apples are alike (See chart 1).

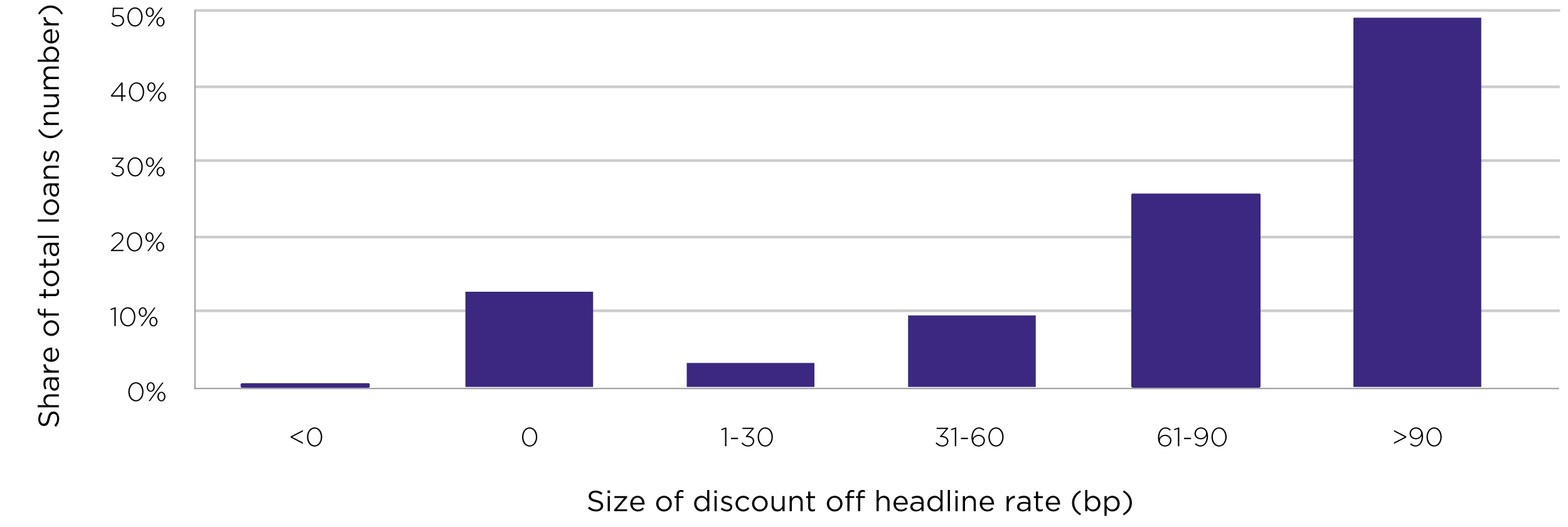

Chart 1: Total variable residential mortgage book by size of discounts – 30 June 2017

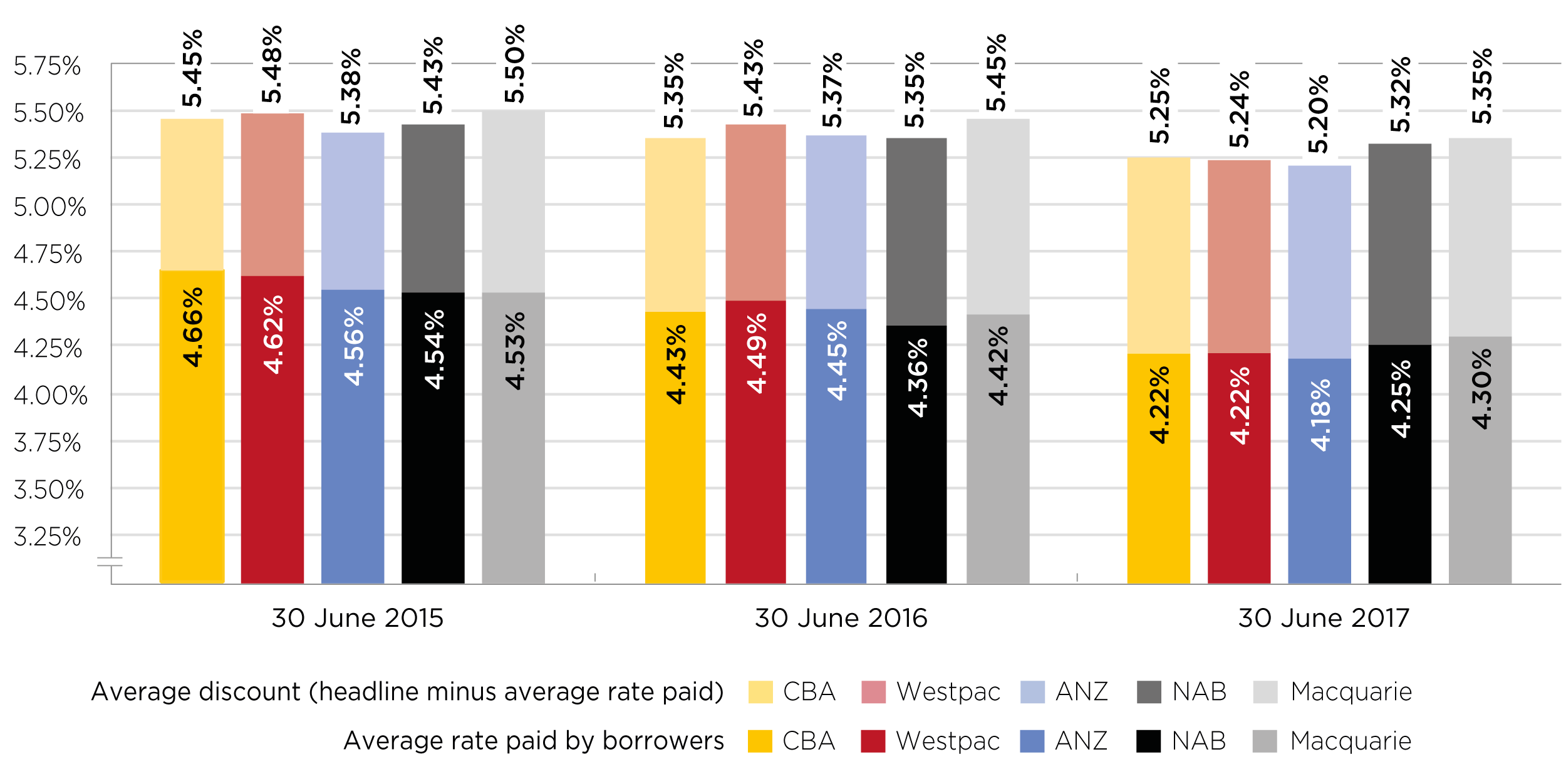

The headline price is a starting price which may then vary by as much as 78–139 basis points below the applicable headline interest rate.

Over the life of an average loan, and this is crucial, we are talking about discounts which amount to life-changing amounts of money for average income earners.

These discretionary discounts do give borrowers a better price, but easy comparison is almost impossible.

Lenders determine discretionary discounts against a range of criteria, some of which are opaque to the borrower.

Since the decision criteria for discretionary discounts vary across lenders, borrowers can find it difficult to determine in advance what, if any, discount they may be eligible for.

Further, discretionary discounts may only be applied and known deep in the application process, and borrowers may even be required to lodge a loan application to confirm the discretionary discount available to them.

And to compare one product with another, the whole process needs to be repeated each time.

Borrowers essentially need to go through the time-consuming process of lodging an application with multiple lenders in order to make an informed decision.

These requirements increase the time and effort associated with obtaining accurate interest rate offers, making it difficult for borrowers to determine the range of effective interest rates available to them (see chart 2).

Chart 2: Headline and average interest rates7 paid for standard8 variable interest rate residential mortgages —owner-occupier with principal and interest repayments9

Offers for new customers versus rates available to existing customers

When it comes to residential mortgages, it pays to be a new customer as discounts are a key tool used by residential mortgage lenders to secure new borrowers.

Due to the difficulty of changing your existing loan, existing customers are assumed to be ‘locked in’. For good reason. In most cases, they are.

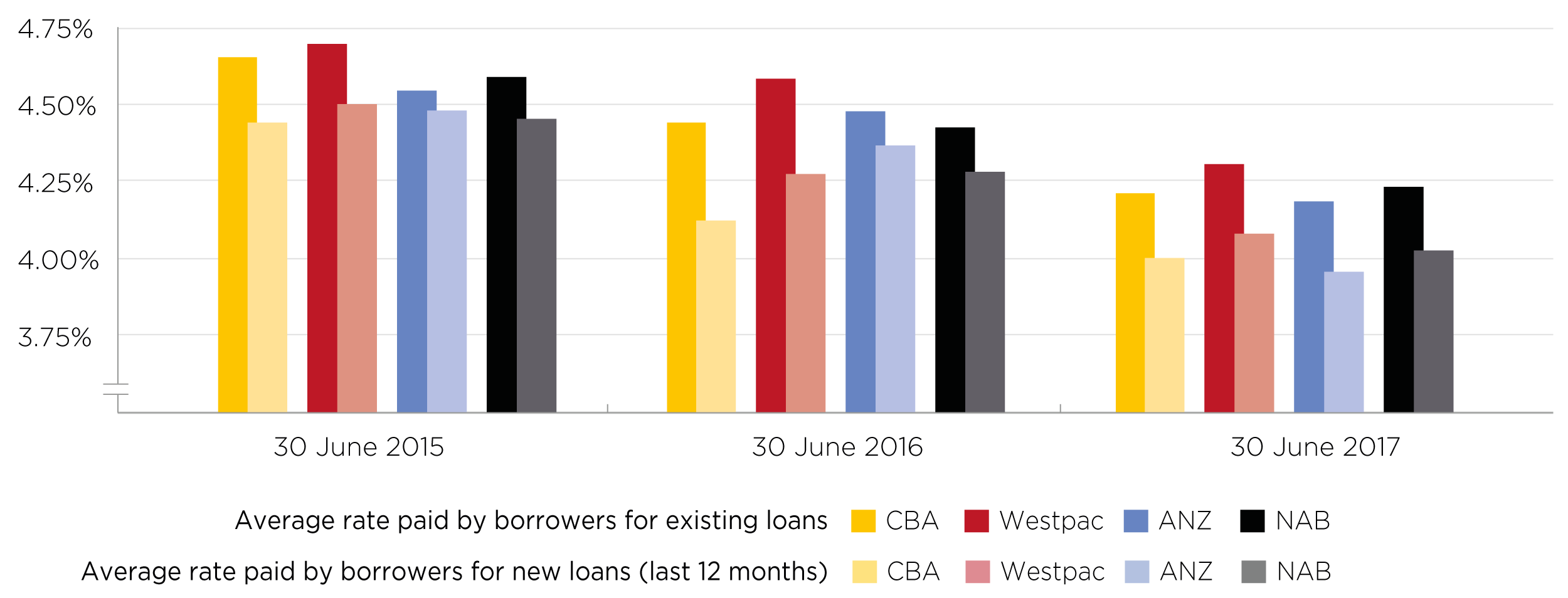

In recent years, residential mortgage lenders have been increasing the discounts offered to their new borrowers compared to the discounts offered to new borrowers in the past (see chart 3).

This practice has resulted in new residential mortgage borrowers often paying a lower interest rate than existing borrowers.

Based on data supplied by the big four banks for 30 June 2015, 30 June 2016 and 30 June 2017, existing borrowers on standard variable interest rate residential mortgages were paying interest rates up to 32 basis points higher (on average) than new borrowers.

Chart 3: Average interest rates paid on standard10 variable interest rate residential mortgages by new and existing borrowers—owner-occupier with principal and interest repayments

On a $375,000 mortgage, 32 basis points would save approximately $1200 in interest over the first year of a loan alone.

Banks are clearly saying to their customers: “if you want a lower interest rate you will need to keep switching lenders.”

Why discounts do not indicate vigorous competition

In response to the above, the banks and their representatives have said that, in effect, “discounts indicate vigorous competition”.

Discounting is not, however, synonymous with vigorous price competition.

For example, and at its most basic, if a monopolist or oligopolist offers a 10% discount on a price already inflated by market power, we wouldn’t say this is evidence of vigorous price competition.

In residential mortgage lending, “discounts” are a measure of a gap between the actual rate charged by the bank and a reference or headline rate that the bank decided for itself and that almost nobody ever pays.

This tells us very little about the vigour of price competition, particularly if the headline rate provides for a profit margin that is inflated well above what is needed to cover any notion of the risk-adjusted return on capital.

Moreover, the ability of the banks we investigated to selectively offer higher discounts to some types of customer, and maintain lower discounts to others, indicates an ability to refrain from vigorous price competition at least with respect to some types of customers.

Our observation that loyal customers pay higher mortgage interest rates, on average, than new borrowers indicates clearly that loyal customers are not seeing the benefits that vigorous price competition would be expected to provide.

The finding about a lack of vigorous price competition was the focus of most attention when we released our report last month.

Little wonder.

It goes to the heart of the problem in banking and confirms long-held consumer suspicions.

Internal documents reviewed by the ACCC reveal a lack of vigorous price competition between the five Inquiry Banks (ANZ, Commonwealth, NAB, Westpac and Macquarie), and the big four banks in particular. In fact, their behaviour more resembles synchronised swimming than it does vigorous competition.

What we found is that the pricing behaviour of the Inquiry Banks appears more consistent with ‘accommodating’ a shared interest in avoiding the disruption of mutually beneficial pricing outcomes, rather than vying for market share by offering the lowest interest rates.

This manifests in at least four ways:

- The big four banks largely focus on each other when they determine headline interest rates and discounts on variable rate residential mortgages. This means the actions and reactions of over 100 other residential mortgage lenders do not appear to have much bearing on interest rate decisions for the big four banks’ main brands. This is important as the big four represent approximately 80 per cent of all outstanding residential mortgages held by banks in Australia.

- The Inquiry Banks generally have not often sought to compete by offering the lowest headline variable interest rate to borrowers.

- The banks usually move their interest rates at the same time, and in response to RBA changes in the overnight cash rate.

- During late 2016 and early 2017, two of the big four banks (independently of each other) decided to take action to reduce discounting in the market. They each reduced their own discounts and sought to trigger reduced discounting by rivals, even though this was likely to be costly for them if other banks did not follow their lead. We observed that by early 2017 the two banks considered they had been successful in leading competitors to reduce discounts for a time.

These are the observed behaviours.

Then there are the internal communications.

In 2015, for example, we saw references to the need to avoid disrupting mutually beneficial pricing outcomes.

There were also references to “encouraging rational market conduct”, “maintaining orderly market conduct” and maintaining “industry conduct”.

There were also references to a desire to have interest rates that are “mid-ranking”, and to the need not to “lead the market down”.

Comments like these are at odds with banks’ assurances and the reasonable community expectations that competition in the sector is vigorous and effective.

2. Data as competition driver

From a competition perspective, it could be argued that ‘customer stickiness’ is an issue for the customer to resolve.

Fair point. Up to a point.

A study by one Inquiry Bank into customer refinancing requests found that where an existing borrower requests a discount, the Inquiry Bank only needs to come close to the discount requested in order to retain the borrower.

That Inquiry Bank observed in a presentation to its executives in the residential mortgage lending division in June 2015 that “where we allowed repricing to occur, customers are price inelastic when the discount offered is close to their requested discount”.

For this reason, residential mortgages and personal banking more generally make one of the strongest cases I have seen for data portability and data access by customers to overcome the inertia of changing lenders.

As an organisation, the ACCC is more than pleased with Treasury’s Report of the Review into Open Banking and its recommendations as it outlines a framework for a consumer data right.

As the Treasurer noted:

Granting third-party access to a customer’s data will allow rival providers to offer competitive deals, products that are tailored to individual needs, and enhanced services that simplify the choices customers face when accessing banking services.

It should simplify the process of switching between banks and help to overcome the ‘hassle factor’ that sees customers stay with their current bank even in the presence of more competitive deals elsewhere.12

At worst, the ‘hassle factor’ of comparing and switching should be a bug in the system; it shouldn’t be a feature which benefits an industry lacking in vigorous competition.

The Government has announced that the ACCC will be the lead regulator for the consumer data right, with strong support from the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner.

The consumer data right was, of course, the brain child of the Productivity Commission in a report to the Government last year.

The ACCC’s proposed roles include making rules to implement the specifics of the data right, and taking enforcement action to ensure that participants in the new framework meet their obligations.

We are undertaking preparatory work in anticipation of this new role, recognising that formal commencement will be determined once the government has finalised its response to the Open Banking report.

3. Stability versus competition

This is a topic we avoid, but it is one we must talk about.

In recent public statements, particularly in response to the recent Productivity Commission draft report on Competition in the Australian Financial System, senior bank representatives have suggested that prudential regulation and other supportive measures are vital to keep them strong.

They also argue, however, that they are commercial enterprises and as such, must be allowed to pursue an objective of maximising shareholder value.

I believe there is a tension in these two positions that needs to be examined further.

But beyond this tension, we must recognise that the poor performance and failures of banks worldwide, that have often prompted enhanced stability measures, were not caused by excessive competition. Quite the contrary.

Often they appear to have been caused by inappropriate behaviour and endemic short termism, possibly driven by a desire for huge bonuses.

The current Banking Royal Commission is also revealing further failures that cannot be blamed on strong competition.

On the contrary, if we continue to insulate our major banks from the consequences of their poor decisions, we risk stifling the cultural change many say is needed within our major banks to put the needs of their customers first.

There is a, perhaps old fashioned view, that facing strong competition forces firms to increase their focus on customer outcomes.

I think this holds for all sectors of economy, including the banking sector.

Vigorous competition is a powerful mechanism for driving improved efficiency, and also for driving improved price and service offerings to customers.

Culture change to deliver better outcomes for consumers will not occur because the community, regulators or perhaps even some bankers wish it to happen.

Competition is not, repeat not, welcomed by businesses. This is because it delivers better outcomes for consumers. This is exactly what seems to be needed in our banking system.

The ACCC is deeply involved in helping consumers find and achieve lower prices in areas of essential purchases, from electricity to petrol. But most consumers spend significantly more on various financial products, particularly servicing their home mortgage.

Financial stability will be helped by more competition. More importantly, so will consumers.

Conclusion

Ladies and gentlemen, the ACCC’s mandate is to promote competition and fair trading.

It is clear from our interim report into residential mortgage pricing that there are significant issues in the banking sector which raise concerns about competition in the sector as well as fair trading.

Soon after June 30 this year, the ACCC will be releasing its final report into residential mortgages. Our focus will then turn to how best to promote competition in the industry more generally and we will proactively identify issues to examine, particularly leveraging off the work of the Productivity Commission.

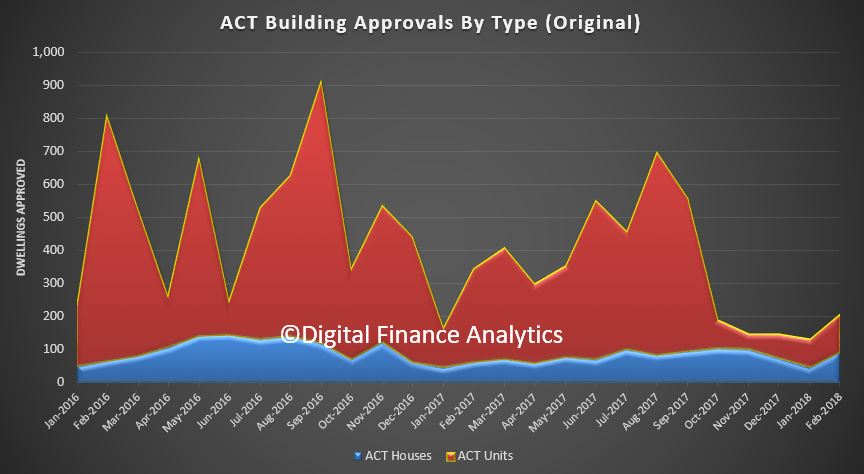

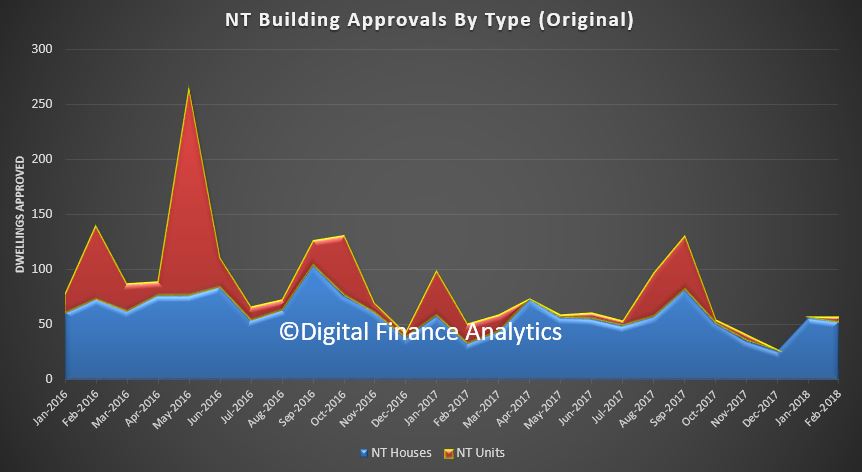

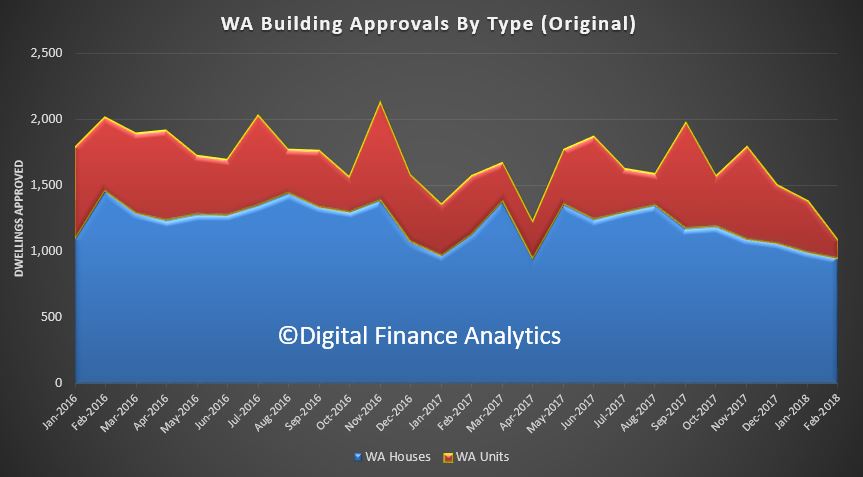

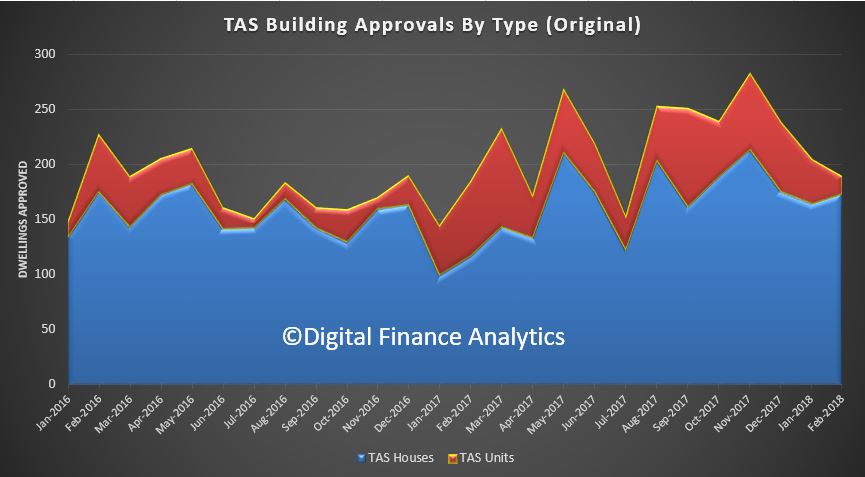

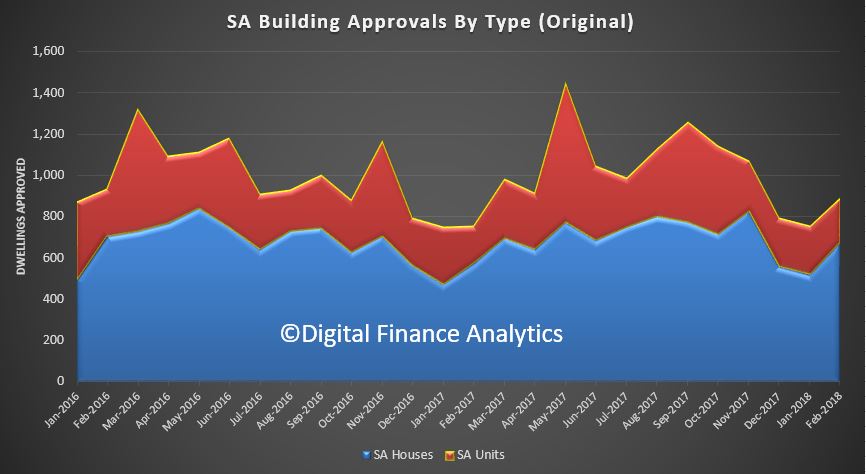

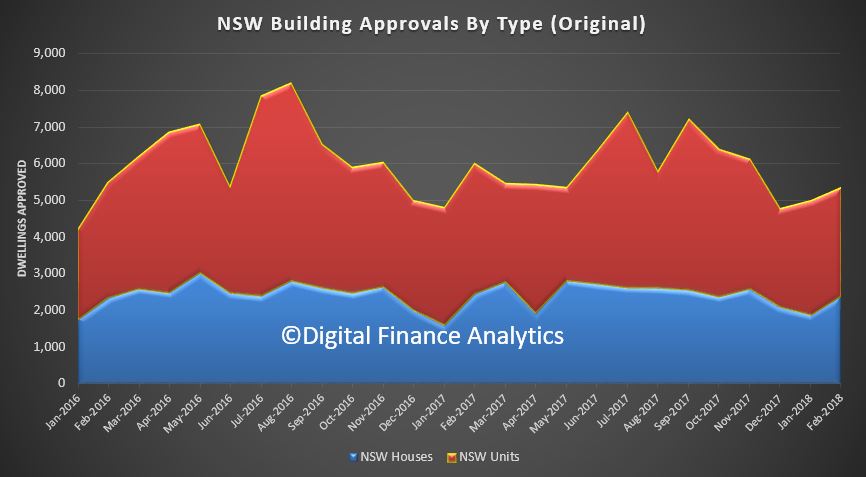

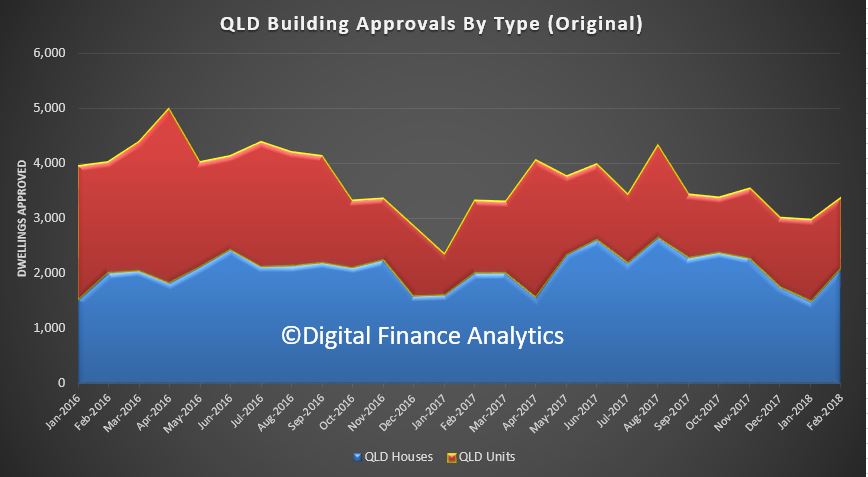

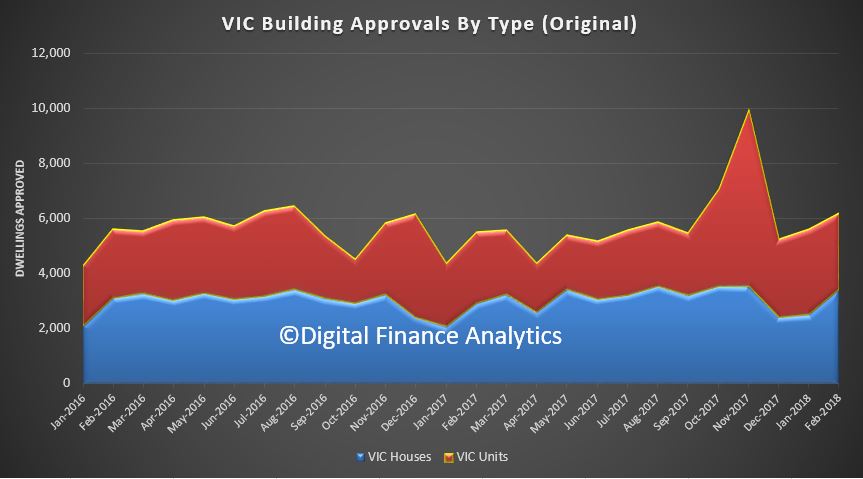

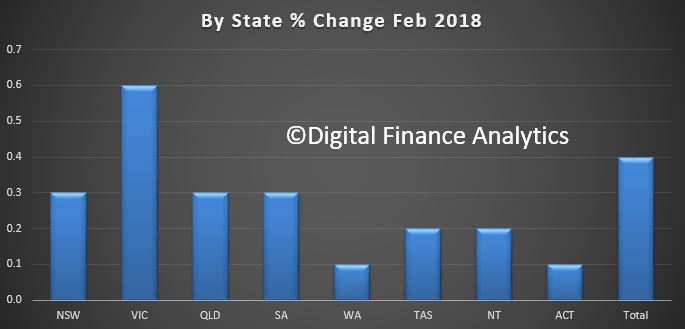

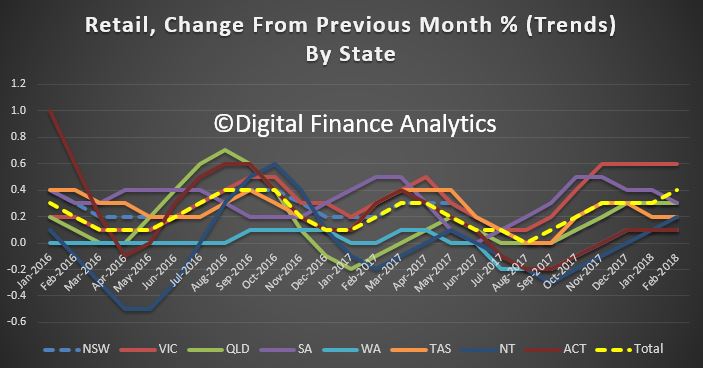

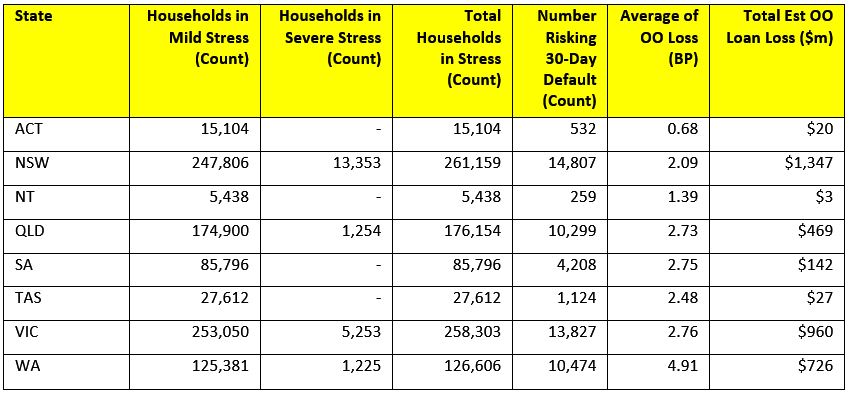

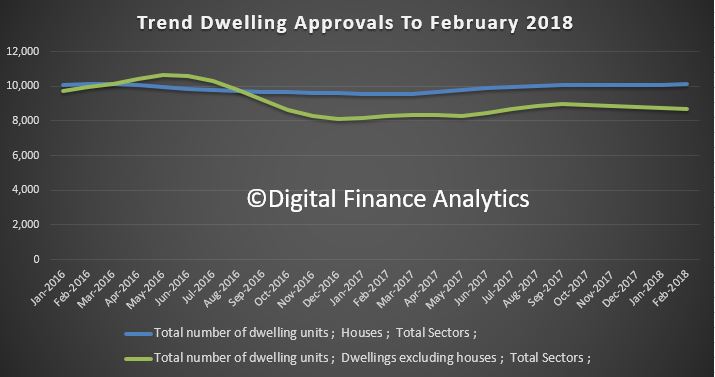

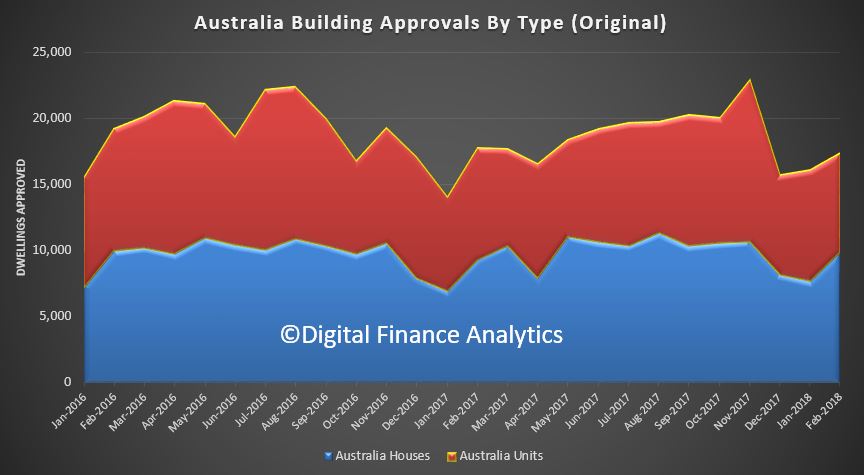

We can then look across the individual states, as there are significant variations. Among the states and territories, the biggest trend decrease in dwelling approvals in February was the Australian Capital Territory down 18.7 per cent,

We can then look across the individual states, as there are significant variations. Among the states and territories, the biggest trend decrease in dwelling approvals in February was the Australian Capital Territory down 18.7 per cent,