The game is up. Major changes are rippling through the property market, with continued pressure on many households, so we examine the latest data.

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to 13 January 2018. Watch the video or read the transcript.

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to 13 January 2018. Watch the video or read the transcript.

In this week’s review of the latest finance and property news, we start with the AFG Mortgage Index with data to December 2017. While the view is myopic (as its only their data) it is useful and really highlights some of the transitions underway in the industry. First, there has been an astonishing drop in the number of interest only loans being written, from 60% of volume in 2015, to 20% now – WOW! We also see a small rise in first time buyer volumes, as expected. So the regulatory intervention is having some impact. However, average loans size is rising (and faster than income and inflation), and Victoria stands out as the state to watch with an increase in average loan size over the past 12 months nearly double the size of the increase in New South Wales. So more still needs to be done on the regulatory front. Overall, the national average loan size is up 2.8% over the past 12 months. The average loan size in New South Wales is now $613,084. Queensland has increased by 3.4% to now be sitting at $416,921. South Australia is up 3.4% to $390,706. The Northern Territory is up 22% to $469,502, albeit from a low volume. Reflecting the challenges being encountered by the WA economy, the state’s average loan size is down 1.1% to $439,944. Finally, the share of the major’s banks is falling, as we have seen from other data, as smaller players and non-banks pick up the slack. The majors now have just 64.2% of the market compared to the non-majors sitting at 35.8%.

There is more evidence of poor mortgage lending practice, according to online property lender Tic:Toc Home Loans as reported in The Australian Financial Review. This is another version of the ‘liar loans’ story, and shows that borrowers are more stretched than some lenders suspect. Tic:Toc says, one in five property borrowers are exaggerating their income and nearly half understating their spending, triggering new concerns about underwriting standards and vulnerability to sharp economic corrections. We see similar issues in our own surveys, as households stretch to get the largest mortgage they can, whatever the cost, and whatever the risk.

APRA released the final version of the revised reporting requirements for residential mortgage lending. It comes into effect from March and lenders will have to report more fully, including data on gross income, (excluding super contributions), new reporting on self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs) and non-residents, as well as all family trusts holding residential mortgages. Reporting of refinanced loans should include date of refinance (not original funding date) and APRA says the original purpose of the loan is not relevant to reporting when refinanced. Once again we see APRA in catch-up mode trying to get the data to manage the mortgage lending sector more effectively. We think they have been late to the party, and have much to do.

The chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has revealed that there will be some “surprises” in the upcoming draft report into how the banks price residential mortgage products. The inquiry into how the major banks price their mortgage is the first undertaking of the ACCC’s new Financial Sector Competition Unit, which is tasked with undertaking regular inquiries into specific competition issues across the financial sector. Starting with the $1.2 million inquiry into residential mortgage product pricing, the ACCC is aiming to understand how the banks affected by the major bank levy explain any changes or proposed changes to fees, charges or interest rates in relation to residential mortgage products. The inquiry relates to prices charged until 30 June 2018. A draft report will be published in February or March. This will be an important piece of work especially, as the corporate watchdog has also previously warned that the big banks could be in breach of the ASIC Act over the reasons given for hiking interest rates.

Turning to broader economic news, The November data from the ABS shows that Australian retail turnover rose 1.2 per cent in November 2017, seasonally adjusted, with Black Friday and iPhone X sales driving the outcome This follows a 0.5 per cent rise in October 2017. Some will spruke this as a positive sign. However, the more reliable trends are less positive, with the estimate for retail turnover up 0.1 per cent in November 2017 the same as October 2017. This is just 1.7 per cent over that past year, so still weak, reflecting stagnant wage growth, rising costs and high levels of debt. The state trend data showed NSW, ACT and QLD had no change, NT fell 0.2% along with WA, while VIC rose 0.3% and SA 0.4%, and TAS rose 0.2%. Online retail turnover was a new record at 5.5 per cent of total retail turnover. But the key takeaway is that households are continuing to keep their wallets firmly in their pockets.

The latest ANZ Job Ads series for December in seasonally adjusted terms, fell 2.3% largely unwinding the increase over the previous two months. On an annual basis job ads are up 11.4%, a slight moderation from 12.0% y/y growth the previous month. The labour market in 2017 was characterised by widespread job growth (particularly in full time jobs), an increase in participation and a fall in the unemployment rate to a four-year low of 5.4%. Growth in ANZ Job Ads provided a leading signal of this strong performance. But of course this has not been converted to rising wages growth so far.

The Building Approvals data from the ABS was much stronger than expected, with the number of dwellings approved up 0.9 per cent in November 2017, in trend terms, and has risen for 10 months. The strong results were driven by renewed strength in approvals for apartments. Approvals for private sector houses fell 0.1 per cent in November. Private sector house approvals fell in Western Australia (3.3 per cent), New South Wales (0.8 per cent) and Queensland (0.4 per cent), but rose in South Australia (1.3 per cent) and Victoria (1.1 per cent).

Consumer Confidence was stronger in the first week of January according to the ANZ/Roy Morgan index, which jumped 4.7% to 122 last week, leaving it at the highest level since late 2013. It often jumps after Christmas, and perhaps the holidays and ashes victory are colouring perspectives. Certainly, it makes an interesting contrast to our own Household Financial Security Index, which we released this week, based on December 2017 survey data. The latest edition of the Digital Finance Analytics Household Financial Security Confidence Index, fell from 96.1 last month to 95.7 this time, and remains below the neutral measure of 100. You can watch our video where we discuss the research.

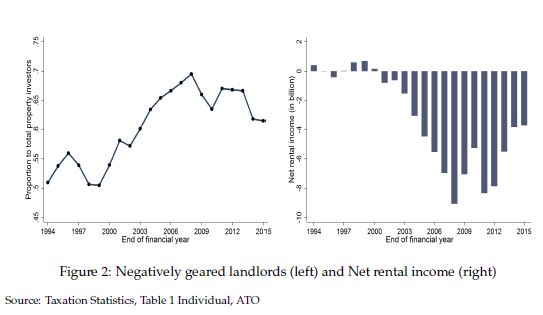

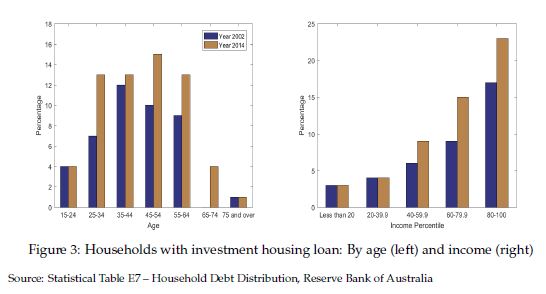

Analysis of households by their property owning status reveals that property investors are in particular turning sour, as flat net rental incomes, and rising interest rates hit many, at a time when property capital growth is stalling. Owner occupied households are faring a little better, thanks to a range of ultra-cheap mortgage rates on offer at the moment, but they are also concerned about price momentum. Those without property interests remain the least confident, as the costs of renting outstrip income growth, and more are slipping into rental stress.

More questions came out this week, when The ABC is reporting that a Treasury FOI request has shown that Federal Labor’s negative gearing overhaul would likely have a “small” impact on home values, official documents reveal, contradicting Government claims the policy would “smash” Australia’s housing market. The previously confidential advice to Treasurer Scott Morrison from his own department said the Opposition’s plan might cause “some downward pressure” and could have “a relatively modest downward impact” on prices. This is further evidence that tackling negative gearing should be a strategic priority to help bring our housing market back to reality.

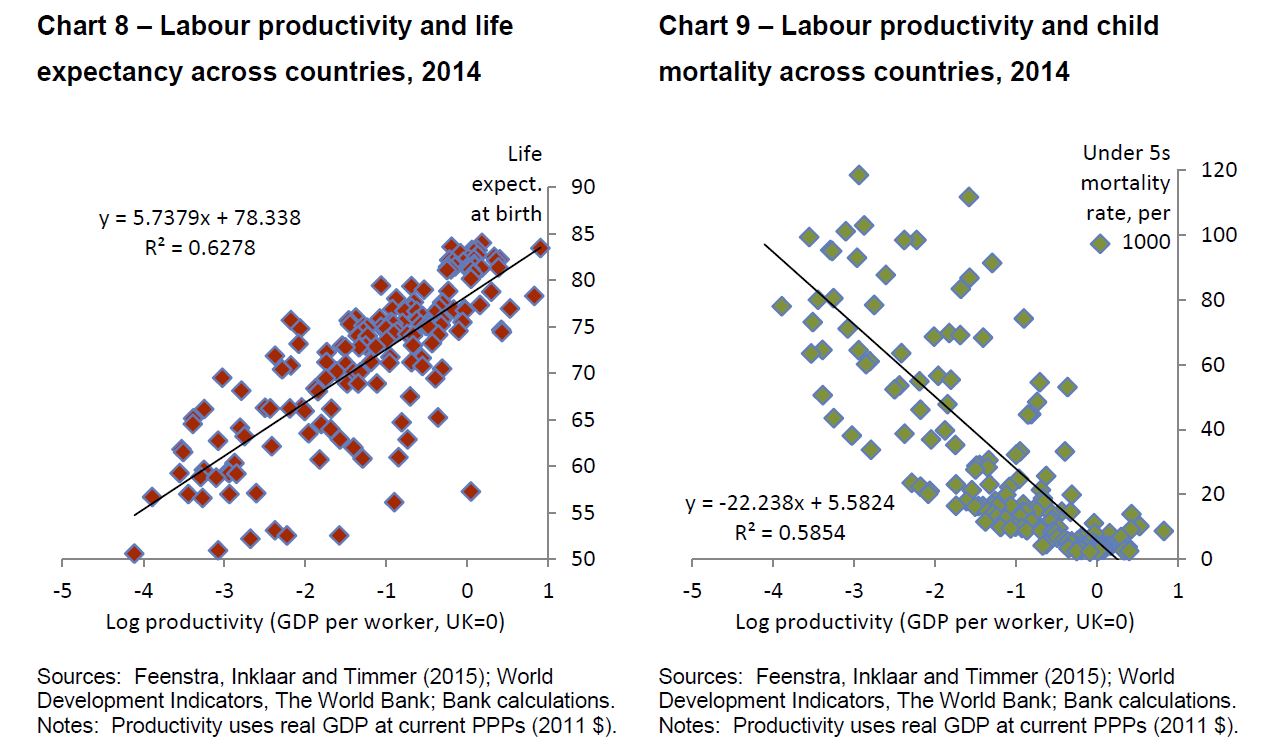

There is also a blind spot at the heart of macroeconomics according to Claudio Borio Head of the BIS Monetary and Economic Department – the BIS is the Central Bankers Banker. He argues that a core assumption implicit in policy setting is that macroeconomics can treat the economy as if it produced a single good through a single firm. The net effect of this assumption is to drag down interest rates and productivity. The truth is much more complex, and within the economy there are “zombie firms” where resources are effectively misallocated, leading to reduced productivity and lower than expected economic outcomes, which will cast a long shadow through the economic cycle. The bottom line is first, credit booms tend to undermine productivity growth as they occur and second, the subsequent impact of the labour reallocations that occur during a financial boom is much larger if a banking crisis follows. This may also help to explain the current gap between employment and wages growth.

Finally, if you want more evidence of the risks in the system look at the RBA chart pack which was released this week. You can watch our video on this, but first, relative to the ultra-low cash rate, actual mortgage rates are rising – no surprise given the rise in mortgage stress we are registering. Next, home loan approvals are on the slide – expect more of this as tighter underwriting standards bite, and many interest only borrowers are forced to switch to higher cost interest and principal loans. Home price indices are trending lower (but still net positive growth overall at the moment). Expect more falls in the months ahead. Household debt continues higher. Now double disposable income, and we have some of the most highly in debt households in the world. Lending growth is still three times income, so this is likely to continue higher. All this is bearing down on household consumption as real income growth stalls. The savings ratio is falling, as households tap these to prop up their finances, OK in the short term, but unsustainable longer term.

In summary, UNSW’s Professor Richard Holden wrote that troubling borrowing and lending markers in the Australian housing market suggest that the lessons from the US mortgage meltdown have not been learned. He rightly draws comparisons with the USA, as we discussed in last week’s Property Imperative, with loose lending standards, a high penetration of interest only loans, many of which will need to be refinanced to higher rate principal and interest loans down the track, and liar loans. Plus, there are questions about where borrowers are getting their deposits from (even drawing from credit cards or borrowing from the Bank of Mum and Dad), and while more loans are originated via brokers, he suggests the banks are myopic to the risks in their portfolio. He says we are still left with highly indebted households who have nearly $2 of debt for every $1 of GDP, a raft of interest-only loans that will soon involve principal repayments, and stagnant wage growth, and concludes “Having lived in the US during the mortgage meltdown I’m sorry to say that I’ve seen this movie before. The question is: why haven’t our bankers?” I would add, our Regulators should answer the same question. We are on the brink; the game is up!

And that’s the Property Imperative weekly to 13 January 2018. If you found this useful, do like the post, add a comment, or subscribe to receive future updates. In the past week our YouTube Channel followers have grown by a third, so thanks to all those who joined and the comments you left. We are busy collecting questions for our next Q&A session, so keep a look out for that.

Meantime, we will be back with more insights in the next few days, and many thanks for taking the time to watch.