In his opening statement to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee, Wayne Byres, APRA Chairman said that Australians can be reassured that the industry is financially sound, and that the financial system is stable.

So that’s OK then!

When I last addressed this Committee, I outlined some of the many ways APRA is accountable to both the Parliament and the Australian people. These measures are crucial for APRA to maintain the trust of industry and the public as we aim to fulfil our mandate as a prudential regulator, promoting financial safety and thereby protecting the interests of bank depositors, insurance policyholders and superannuation members.

The core of APRA’s mission is safety and soundness. Clearly, some of the revelations emerging from the Royal Commission have been disturbing and go to the heart of whether financial institutions treat their customers fairly. However, while institutions have a great deal of work to do to restore trust, I want to emphasise that Australians can be reassured that the industry is financially sound, and that the financial system is stable. That reflects considerable policy reform and hands-on supervision, over a long period of time, designed to build strength and resilience. We don’t know when the next period of adversity will arrive or what will trigger it, but when it does arrive we need to have done what we could to strengthen the financial system so that it can continue to provide its essential services to the Australian community when they are needed most.

The importance of accountability has been one of our key themes this year, and was front and centre with the release in April of our review of executive remuneration practices in large financial institutions. Incentives and accountability can play an important role in driving positive outcomes such as growth, innovation and productivity, and also in deterring behaviours or decisions that produce poor risk-taking and damaging results. Our review found that while policies and processes existed within institutions to align remuneration with sound risk outcomes, their practical application was often weak. We have indicated that we are minded to strengthen the prudential framework to give better effect to the principles we want to see followed – less rewards based on narrow and mechanical shareholder metrics, and greater exercise of Board discretion to judge senior executive performance more holistically. But we have also urged institutions to push ahead with their own improvements, notwithstanding some investor opposition, in light of the long-term commercial benefits that can flow from better remuneration practices.

A lack of accountability for poor outcomes was a theme that also emerged in the Final Report of the Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, which was released earlier this month. The Report is clear and comprehensive, and provides a strong message – not just to CBA but to the entire financial services industry – about the importance of cultivating a robust risk culture, especially when it comes to non-financial risks. We are keen that the Report will be seen not just a road map for CBA, but a useful guide for all institutions in relation to strengthening governance, culture and accountability.

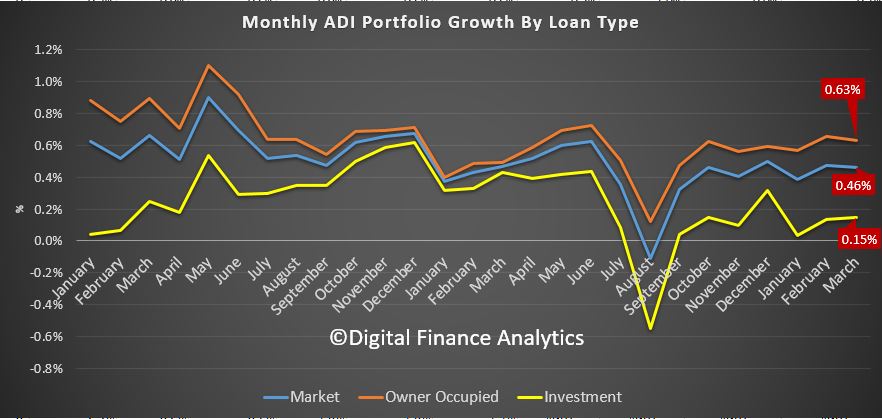

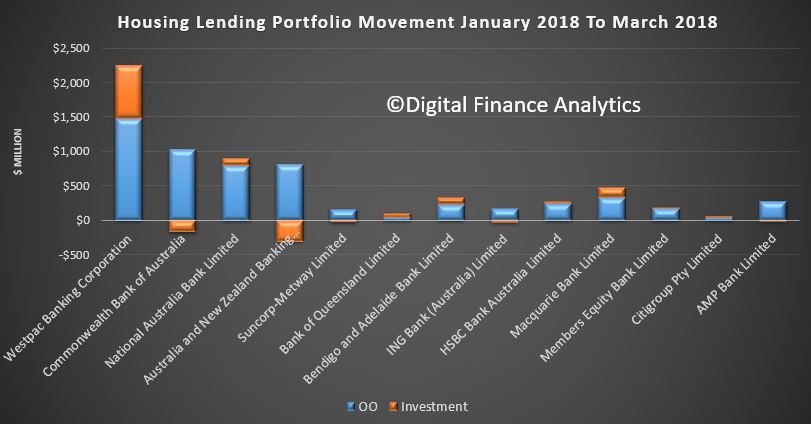

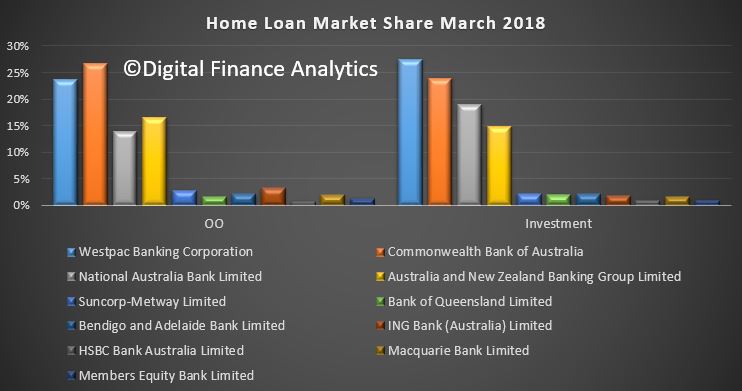

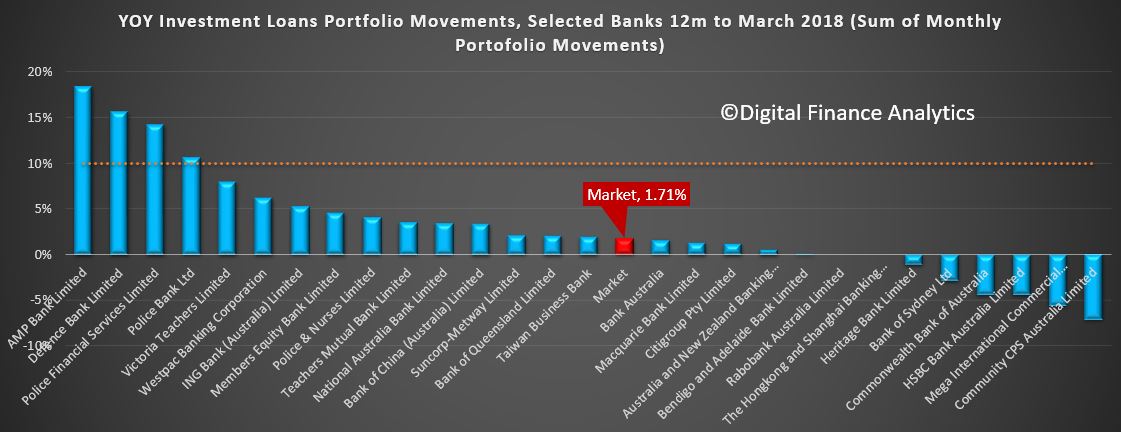

Residential mortgage lending is another area where APRA has been lifting industry standards. Although there remains more to do before we are ready to significantly dial back our supervisory intensity, there has been a lift in industry lending practices. As a result, last month we announced we would remove the 10 per cent investor growth benchmark for those lenders who could provide a range of assurances as to the quality of their lending standards and practices now and into the future.

Superannuation is an area where APRA consistently emphasises the need for trustees, regardless of size or ownership structure, to go beyond compliance with minimum regulatory requirements and aim to deliver the best possible outcomes for members. In this vein, we have just released the results of two thematic reviews of superannuation licensees; on board governance and the management of related parties. Both reviews noted improvements in industry practices in recent years, but also found more work was needed to address some longstanding weaknesses, including finding ways to bring fresh ideas, perspectives and skills onto trustee boards. Our post-implementation review of 2013’s Stronger Super reforms, launched last week, should also provide us additional insights on how the prudential framework is performing, and whether any adjustments would help to better achieve our objectives. Many of the findings in the Productivity Commission report into superannuation released this week are consistent with APRA’s approach to supervising RSE licensees. In particular, they align with APRA’s focus on enhancing the delivery of member outcomes through our engagement with trustees with “outlier” underperforming funds and products.

Technology is rapidly changing the way financial institutions operate. In all likelihood, the financial system will look very different in five years’ time relative to the way it looks today. Much of that change will bring benefits to the community, in the form of new competitors, products and ways of access. But it will also bring risks, and the accelerating threat of cyber-attacks to regulated entities has prompted APRA to recently propose its first prudential standard on information security. Industry consultation is ongoing, but we hope to implement the new cross-industry standard from 1 July next year. This is an issue which is only going to grow in importance.

Continuing to look ahead, APRA’s preparations are well advanced for the commencement of the Banking Executive Accountability Regime (BEAR), which will begin in just over a month. The BEAR largely strengthens APRA’s existing powers to identify and address the prudential risks arising from poor governance, weak culture, or ineffective risk management. However, I have made the point previously that while important, the BEAR alone will not remedy perceived weakness in financial sector accountability, and we have encouraged all regulated entities – not just ADIs – to use the new regime as a trigger to genuinely improve systems of governance, responsibility and accountability.

Finally, APRA is continuing to provide relevant information to the Royal Commission to help it in its inquiries. In addition, APRA and the Australian financial system more broadly, will be subject to intensive scrutiny from the International Monetary Fund in the weeks ahead as part of its 2018 Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP). The FSAP will examine in quite some detail financial sector vulnerabilities and the quality of regulatory oversight arrangements in Australia. As ever, APRA will fully cooperate with our international reviewers, and look forward to their report card, including any recommendations on how we could perform our role more effectively in the future.

With those opening remarks, we would now be happy to answer the Committee’s questions.