Listen, You Can Hear the Screws Tightening On Mortgage Lending. Welcome to The Property Imperative Weekly to 17th February 2018.

Watch the video, or read the transcript.

Watch the video, or read the transcript.

In this week’s digest of finance and property news we start with Governor Lowe’s statement to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics. He continued the themes, of better global economic news, lifting business investment and stronger employment on one hand; but weak wage growth, and high household debt on the other. But for me one comment really stood out. He said:

it would be a good outcome if we now experienced a run of years in which the rate of growth of housing costs and debt did not outstrip growth in our incomes in the way that they did over the past five years.

This is highly significant, given the fact the lending for housing is still growing faster than wages, at around three times, and home prices are continuing to drift a little lower. So don’t expect any moves from the Reserve Bank to ease lending conditions, or expect a boost in home prices. More evidence that the property market is indeed in transition. The era of strong capital appreciation is over for now.

There was lots of news this week about the mortgage industry. ANZ and Westpac have tightened serviceability requirements. Westpac recently introduced strict tests of residential property borrowers’ current and future capacities to repay their loans. The change is said to be intended to identify scenarios that might affect borrowers’ capacity to pay back their loans. These scenarios include having dependents with special needs that might require borrowers to spend on long-term care and treatment. ANZ has added “a higher level of approval for some discretions” used in its home loan policy for assessing serviceability, reducing approvals outside normal terms.

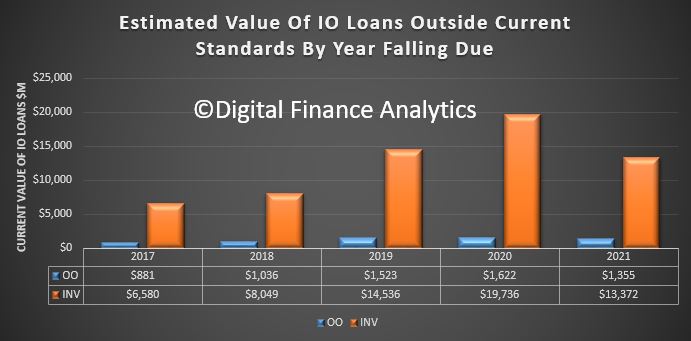

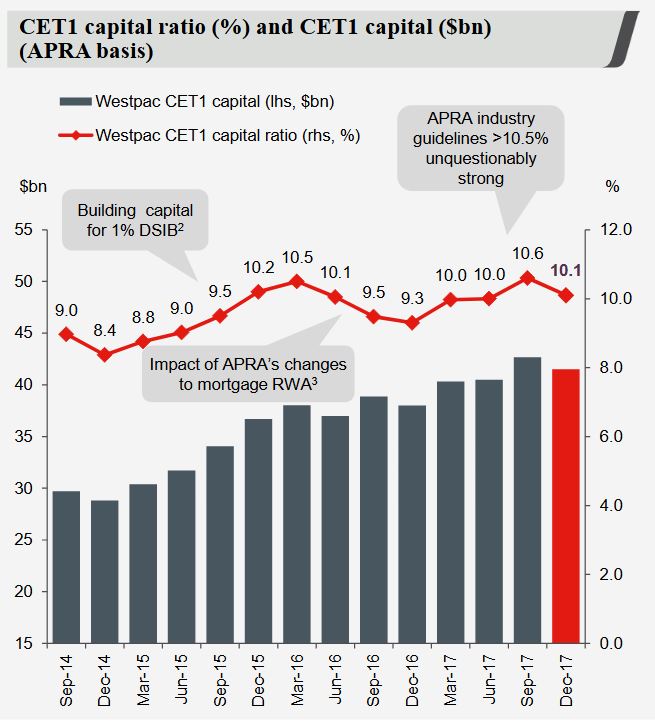

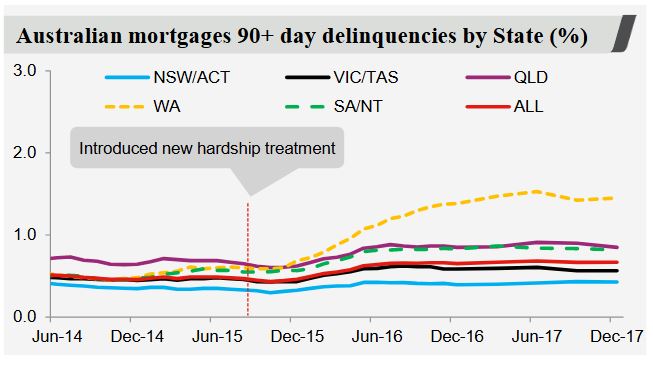

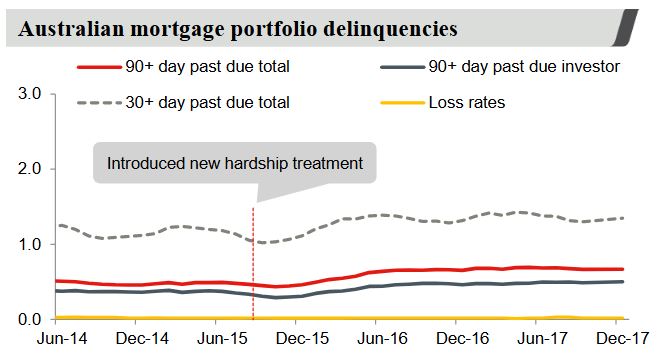

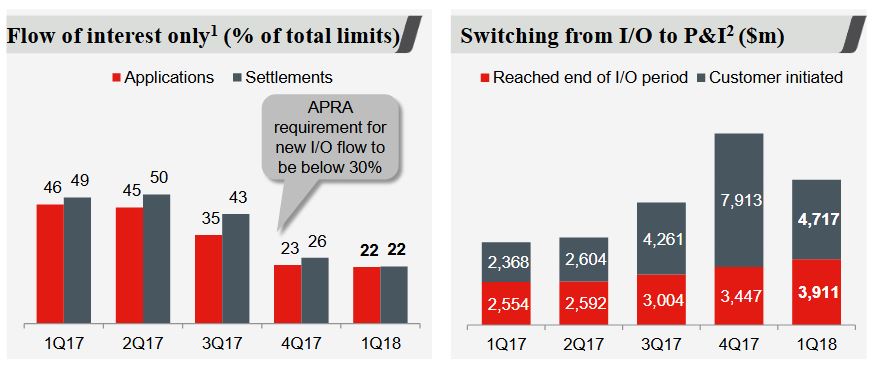

Talking of lending standards, APRA released an important consultation paper on capital ratios. This may sound a dry subject, but the implications for the mortgage industry and the property market are potentially significant. As part of the discussion paper, APRA, says that addressing the systemic concentration of ADI portfolios in residential mortgages is an important element of the proposals. They have FINALLY woken up to the risks in the system, just years too late! We have significant numbers of loans in the system currently that would now not pass muster. More about that next week.

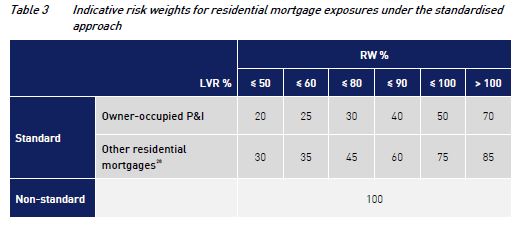

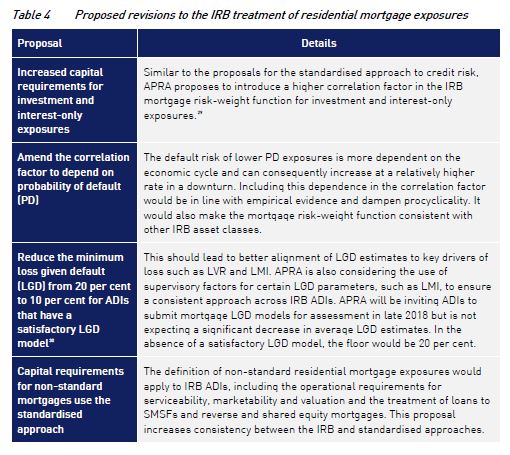

Their proposals, which focus in on mortgage serviceability, would change the industry significantly, as lower risk loans will be more highly prized (so expect low rate offers for lower LVRs), whilst investment loans, and interest only loans are likely to cost more and be harder to find. Combined this could certainly move the market! The proposals introduce “standard” and “non-standard” risk categories.

As well as increasing the risk weights for some mortgages, they also continue to close the gap between the advanced (IRB) internal approach used by large lenders, and the standard approach used by smaller players. Those in transition (e.g. Bendigo Bank) may find less of an advantage in moving to advanced as a result. You can watch our separate video on this important topic.

Whilst the overall capital ratios will not change much, there is a significant rebalancing of metrics, and Banks will more investment and interest only loans will be most impacted. So getting an investment loan will be somewhat harder and this will impact the property market. The proposals are for consultation, with a closing data 18 May 2018.

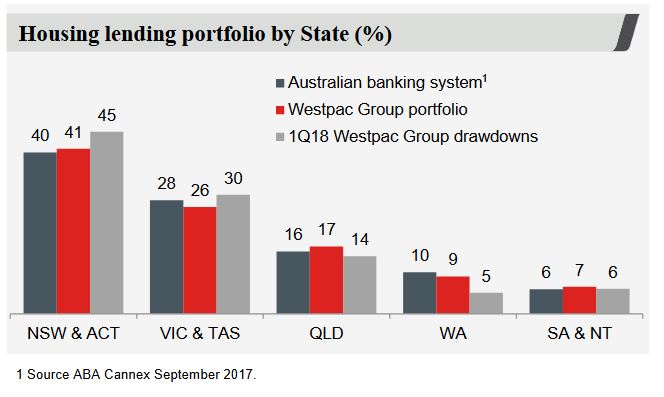

Another data point on the property market came from a new report by Knight Frank which claims that in 2017, one-third of Australian residential development sites were sold to Chinese investors and developers. The share of sales to Chinese buyers has tripled since 2013, but decreased from the 38 per cent recorded in 2016. The level of Chinese investment in residential development sites varied from state to state: in Victoria, 38.7 per cent of residential site sales were to Chinese buyers; in New South Wales, 35.6 per cent of residential site sales were to Chinese buyers, and in Queensland, Chinese buyers comprised 7.4 per cent of total residential site sale volumes. So this is one factor still supporting the market, though in Australia, the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority has encouraged local financial institutions to impose stricter controls, while in China the government has attempted to moderate capital outflow with China’s Central Bank imposing new rules for companies which make yuan-denominated loans to overseas entities.

The data from the ABS on Lending Finance, the last part of the finance stats for December, really underscores the slowing momentum in investment property lending, especially in Sydney (though it is still a significant slug of new finance, and there is no justification to ease the current regulatory requirements.) The ABS says the total value of owner occupied housing commitments excluding alterations and additions rose 0.1% in trend terms, total personal finance commitments fell 0.2%. Revolving credit commitments fell 1.4%, while fixed lending commitments rose 0.5%. There was a small rise in lending for housing construction, but overall mortgage momentum looks like it is still slowing and the mix of commercial lending is tilting away from investment lending and towards other commercial purposes at 64%, which is a good thing.

There is an air of desperation from the construction sector, as sales momentum continues to ease, this despite slightly higher auction clearance rates last week. CoreLogic said the final auction clearance rate was 63.7 per cent clearance rate across almost double the volume of auctions week-on-week (1,470). Over the week prior, a clearance rate of 62.0 per cent was recorded across 790 auctions. Both auction clearance rate and volumes were lower than what was seen one year ago, when a 73.2 per cent clearance was recorded across 1,591 auctions. There is significant discounting going on at the moment to shift property, and some builders are looking to lend direct to purchases to make a sale. For example, Catapult Property Group launched a new lending division that will help first home buyers get home loans with a deposit of only $5,000. The Brisbane-based company encourages first home buyers in Queensland to enter the real estate market now by taking advantage of the state government’s $20,000 grant that is ending on 30 June 2018. This is at a time when lenders are insisting on larger deposits, and are applying more conservative underwriting standards.

Economic data out this week showed that according to the ABS, trend unemployment remained steady at 5.5%, where it has hovered for the past seven months. The trend unemployment rate has fallen by 0.3 percentage points over the year but has been at approximately the same level for the past seven months, after the December 2017 figure was revised upward to 5.5 per cent. The ABS says that full-time employment grew by a further 9,000 persons in January, while part-time employment increased by 14,000 persons, underpinning a total increase in employment of 23,000 persons. The fact is that while more jobs are being created, it is not pulling the rate lower, and many of these jobs are lower paid part time roles – especially in in the healthcare sector. In fact, the growth in employment is strong for women than men. A rather different story from the current political spin!

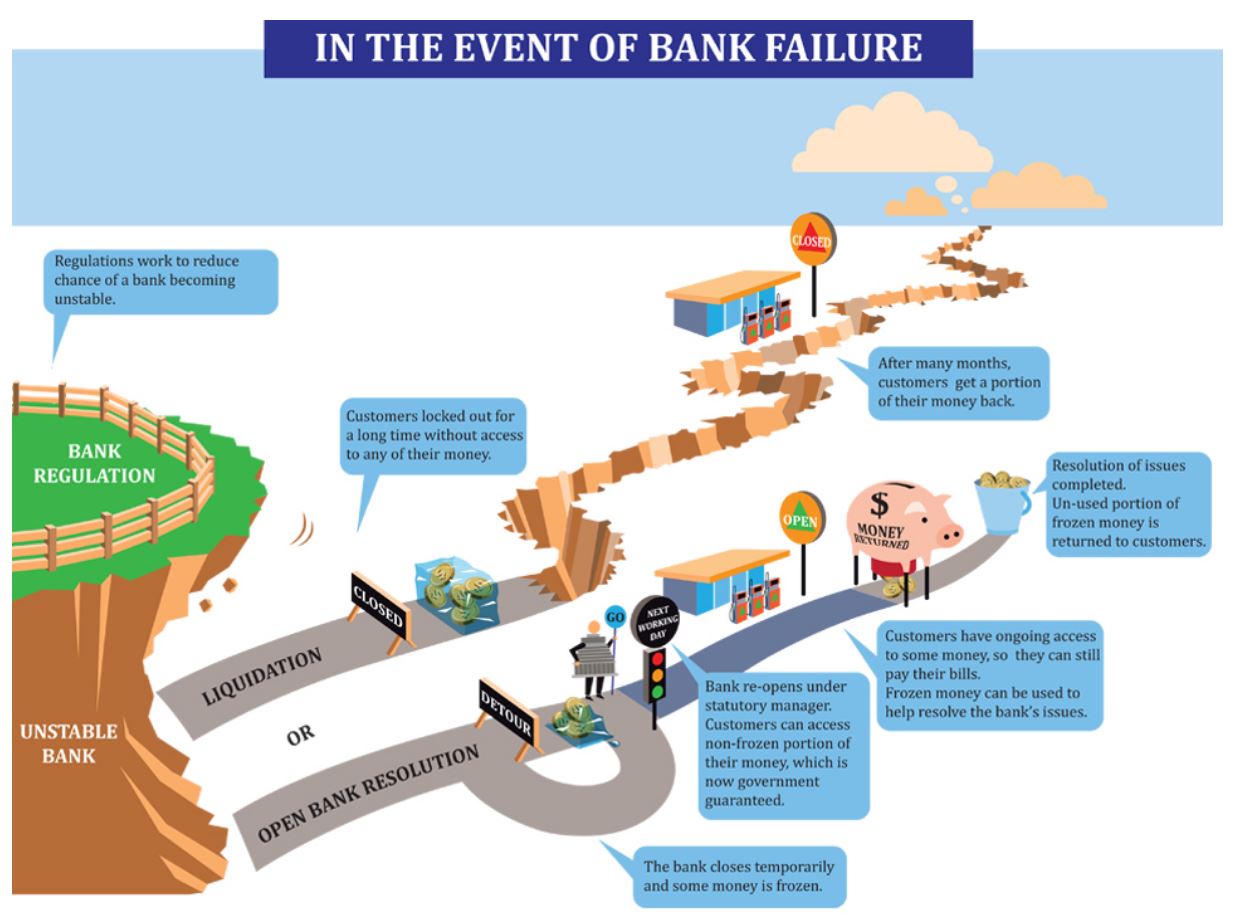

In a Banking Crisis, are Bank Deposits Safe? We discussed the consequences of recently introduced enhanced powers for APRA to deal with a bank in distress this week. There were several well publicised Government bail-out’s of banks which got into problems after the GFC. For example, the UK’s Royal Bank of Scotland was nationalised. This costs tax payers dear, so there were measures put in place to try to manage a more orderly transition when a bank gets into difficulty and raises the question of “Bail-in” arrangements. Take New Zealand for example. There regulators have specific powers to grab savings held in the banks in assist in an orderly transition in the case of a failure, alongside capital and other bank assets. And, given the New Zealand position (and the tight relationship between banking regulators in Australia and New Zealand), we should look at the position in Australia. Are deposit funds in Australia likely to be “bailed-in”? Well, the Treasury confirmed that because deposits are not classified as capital instruments, and do not include terms that allow for their conversion or write-off, they cannot be ‘bailed-in’. But we have a catch all clause in APRA’s powers that says they can grab “any other instrument” and deposits, despite the Treasury reassuring words, is not explicitly excluded. So I for one cannot be 100% convinced savings will never be bailed-in. And that’s a worry! I recall the Productivity Commission comment last week, that financial stability had taken prime place compared with competition (and so customer value) in financial services. The issue of bail-in of deposits appears to be shaping the same way. You can watch our separate video discussion on this important topic.

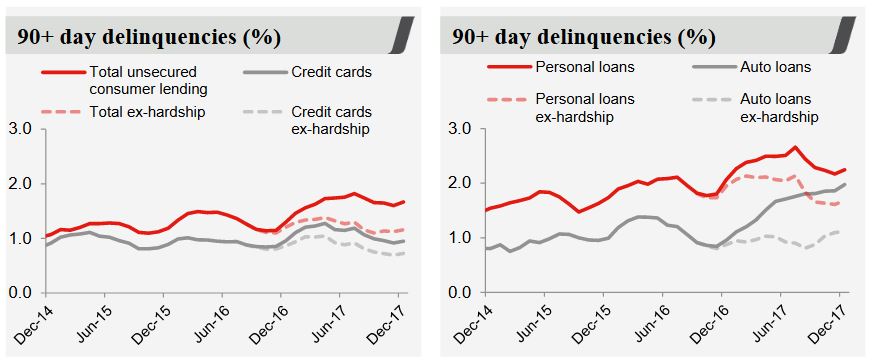

The first round of public hearings for the Banking Royal Commission will focus on lending, including mortgages, credit cards and car loans; we heard during the opening session. The Commission highlighted the large size of the lending market, and the significant number of submissions they have already received on misconduct in this area, including relating to intermediaries, commission and advice. In addition, as part of the opening address, we were told that some of the major players were unable to provide the full range of misconduct information that Commission requested. Some players offered a few case studies, and were then asked to provide more detail over the past 5 years (as opposed to 10) but said they could not meet the required deadline. Based on the opening round, Banks are going to find this a painful process. Not least because The Commission is publishing information on the sector. In its first release, it pointed to declining competition in the banking sector, with the number of credit unions falling due to consolidation and the major banks holding 75 per cent of total assets held by ADIs in Australia. The paper noted that five of the 20 listed companies that make up the ASX20 are banks, noting that the major banks have “generally achieved higher profit margins than other types of ADIs” with a profit margin of 36.4 per cent in the June quarter 2017. They also underscored that Australia’s major banks are “comparatively more profitable” than some of their international peers in Canada, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

We expect to hear more from the Royal Commissions on unfair and predatory practices. To underscore this there was some good news for Credit Card holders, with new legalisation passed in parliament to force Credit card providers to scrap unfair and predatory practices. However, the implementation timetable is extended into 2019. The reforms include:

Requiring affordability assessments be based on a consumer’s ability to repay the credit limit within a reasonable period (from July 2018). This tightens responsible lending obligations for credit card contracts.

Banning unsolicited offers of credit limit increases (from January 2019). At the moment, whilst the law forbids providers from making these sorts of offers in writing, offers can be made by phone and other mediums. This loophole has been exploited, but will now be closed.

Simplifying how credit card interest is calculated, especially, banning the practice of backdating interest rate charges. Currently, some providers were attracting new customers with promotional low rate, or no rate offers, say for the first month. But, if a customer failed to pay off in full a credit card bill after the first month, the credit card company was often retrospectively applying the new interest rate to previous purchases. This was allowed in the banks’ small print, but the government said the practice did “not align with consumers’ understanding and expectation about how interest is to be charged”. This will be banned, from next year.

Requiring credit card providers to have online options to cancel cards or to reduce credit limits (from January 2019). At the moment, some card providers force customers to come into a bank branch to reduce limits or terminate cards, and when they did come in were often persuaded not to do it. The asymmetry between fast credit card approvals online, and slow cancellation will end.

So another week highlighting the stresses and strains in the banking sector, and the forces behind slowing momentum in the property market. And based on the stance of the regulators, we think the screws will get tighter in the months ahead, putting more downward pressure on mortgage lending home prices and the Banking Sector. Something which the RBA says is a good thing!