An excellent speech by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England which paints some useful pictures about the future of Fintech and the need to break the mould.

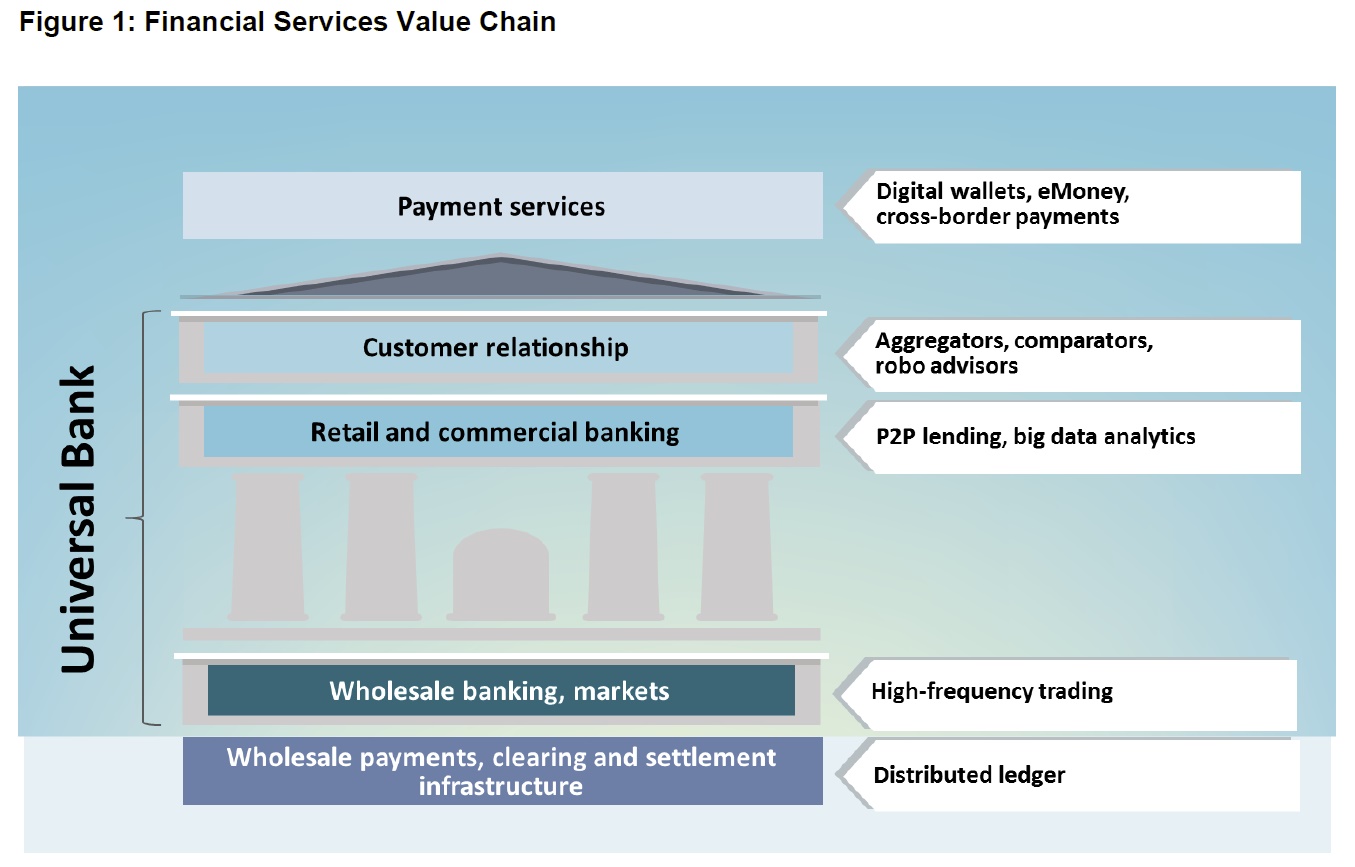

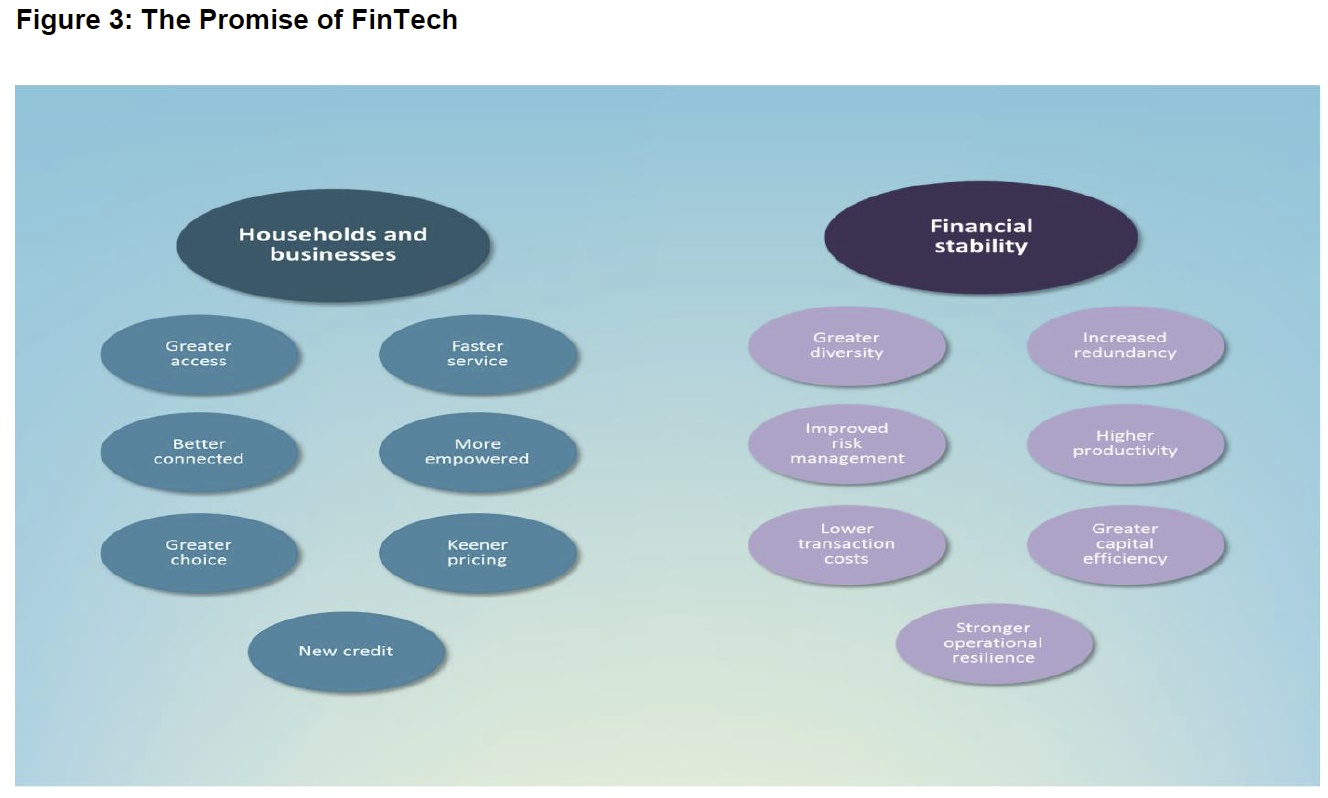

To its advocates, FinTech will democratise financial services. Consumers will get more choice and keener pricing. SMEs will get access to new credit. Banks will become more productive, with lower transaction costs, greater capital efficiency and stronger operational resilience. Financial services will be more inclusive; with people better connected, more informed and increasingly empowered. And tantalisingly, FinTech could help make the system itself more resilient with greater diversity, redundancy and depth.

These possibilities are why the Bank has already taken a number of steps to encourage FinTech’s development. The PRA and the FCA have changed their authorisation processes to support new business models. The New Bank Start-Up Unit, created in 2016, works closely with firms seeking to become banks. Already, four new ‘mobile’ banks have been authorised.

The Bank also established a FinTech Accelerator last year. Since then, we have worked with a number of firms on proofs of concept ranging from strengthening our cyber security to using AI for regulatory data, and improving our understanding of distributed ledgers.

Today we are opening our 4th round of applications to the Accelerator. We are looking to work on new proofs of concept on maintaining privacy in a distributed ledger and applying a range of big data tools to support the Bank’s analysis.

More broadly, the Bank is working to ensure that this time the right hard and soft infrastructure are in place to allow innovation to thrive while keeping the system safe.

Let me expand briefly with three examples.

The Right Soft Infrastructure

First, with respect to soft infrastructure, the Bank is assessing how FinTech could change risks and opportunities along the financial services value chain. We are then using our existing frameworks to respond where necessary.

We are disciplined. Just because something is new doesn’t mean it should be treated differently. Similarly, just because it is outside the regulatory perimeter doesn’t mean it needs to be brought inside. We apply consistent approaches to activities that give rise to the same risks regardless of whether those are undertaken by old regulated or new FinTech firms.

Some of the most important questions we are considering include:

- Which FinTech activities constitute traditional banking activities by another name and should be regulated as such?

- How could developments change the safety and soundness of existing regulated firms

- How could developments change potential macroeconomic and macrofinancial dynamics including disruptions to systemically important markets? And

- What could be the implications for the level of cyber and operational risks faced by regulated firms and the financial system as a whole?

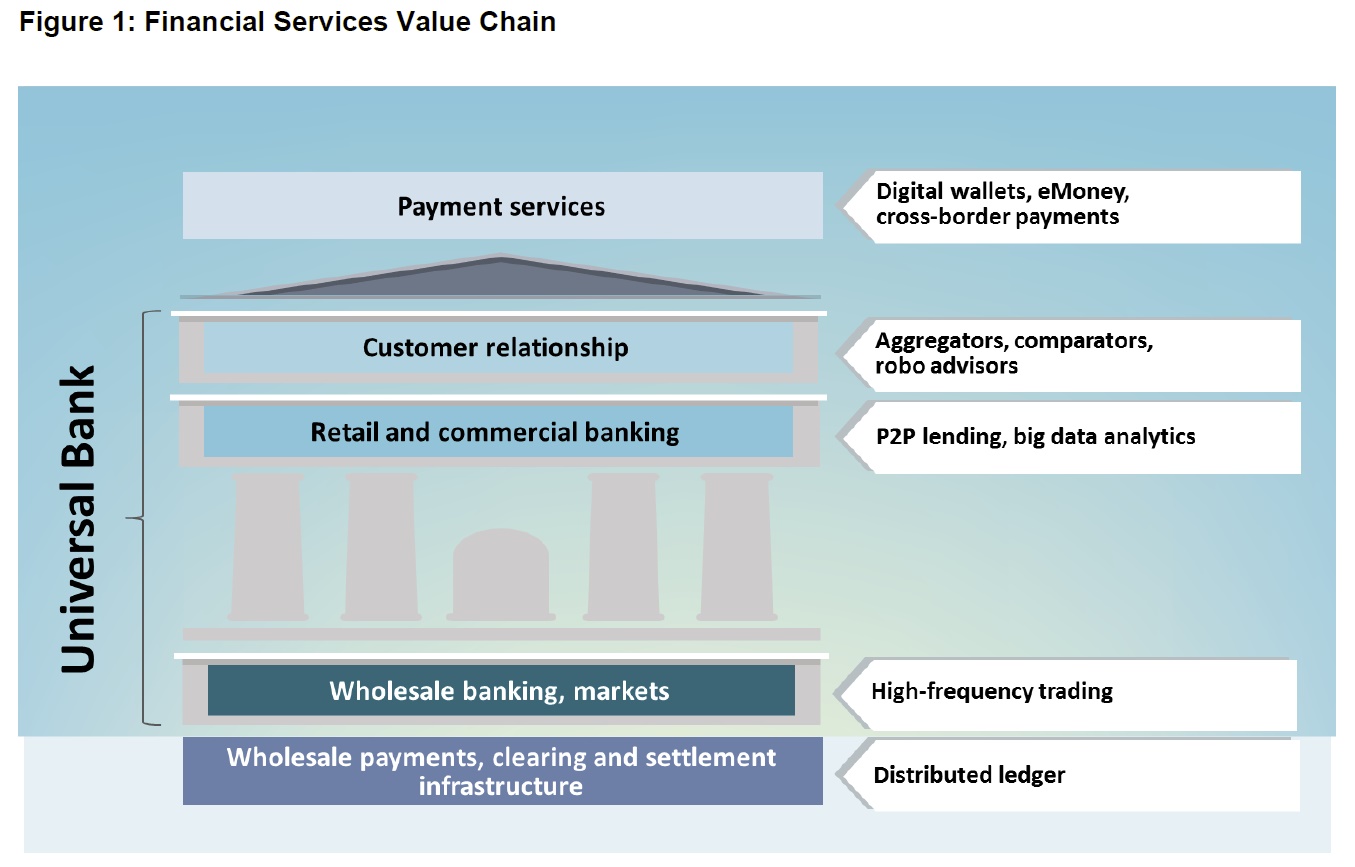

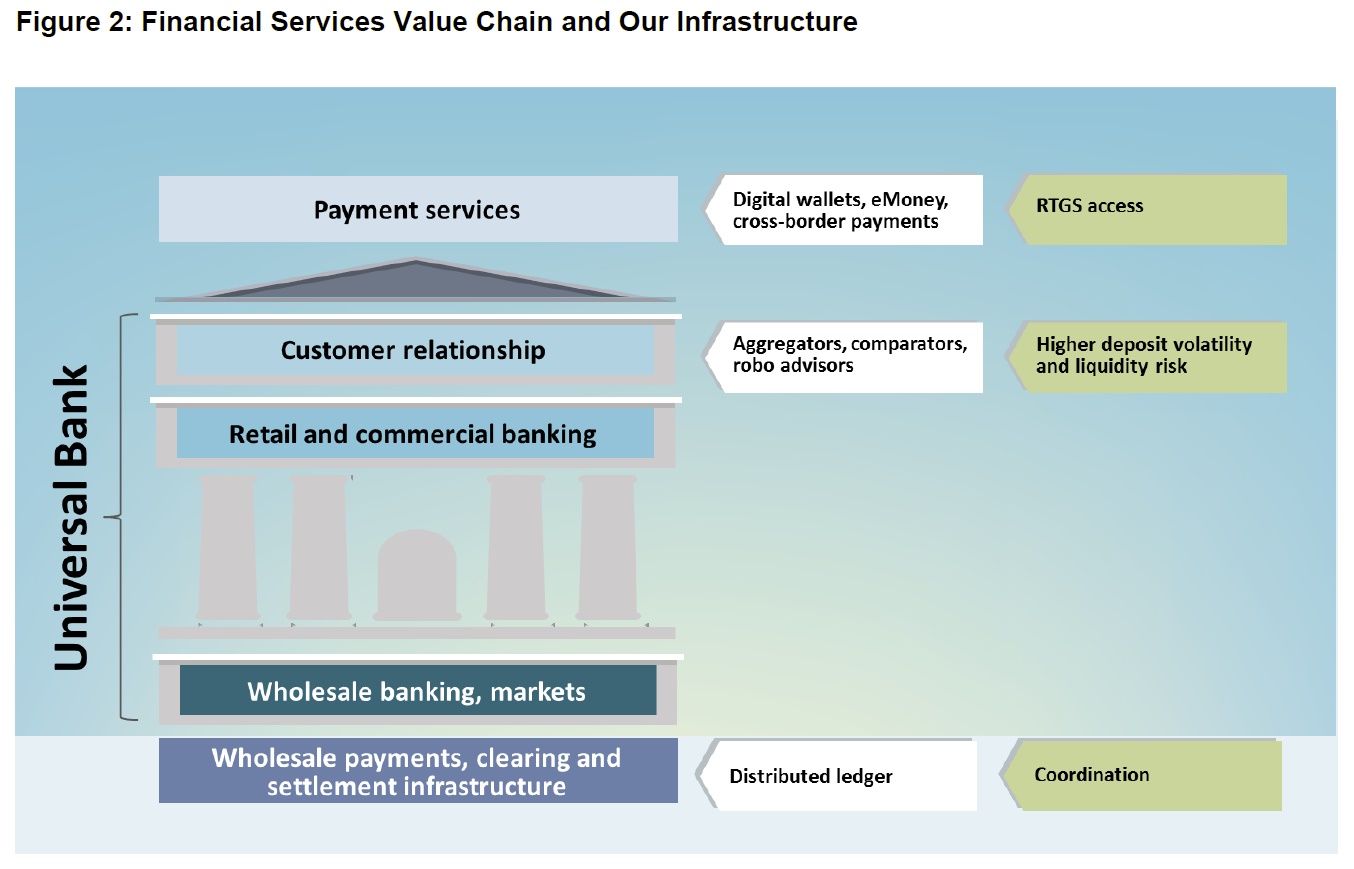

To illustrate some of the issues, consider how FinTech is affecting the financial services value chain (Figure 1).

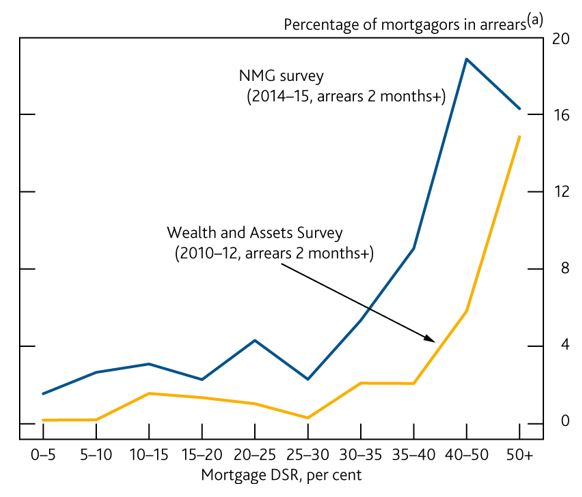

At present, the most significant changes are taking place at the front-end, where innovative payment service providers (PSPs) are providing new user interfaces for domestic retail and cross-border payment services through digital wallets or pre-funded eMoney.Other aspects of the customer relationships are being opened up. For example, aggregators are providing customers with ready access to price comparison and switching services. This will increase further when aggregators gain access to banks’ Application Programme Interfaces (APIs).These new entrants are capturing potentially invaluable customer data which can be used to target non-bank products and services.

In their current form, these innovations are simply a new front-end to the banking system where FinTech providers take a slice of customer revenue and loyalty but none of the associated risks.They have generally avoided undertaking traditional banking activities. So for now, absent a substantive change in business models or scale of activities, the FPC is unlikely to want to bring these firms into the regulatory perimeter.The changes to customer relationships resulting from FinTech competition could, however, reduce customer loyalty and the stability of funding of incumbent banks. If this happens, the Bank of England would need to ensure prudential standards and resolution regimes for the affected banks are sufficiently robust to these risks.

The Right Hard Infrastructure

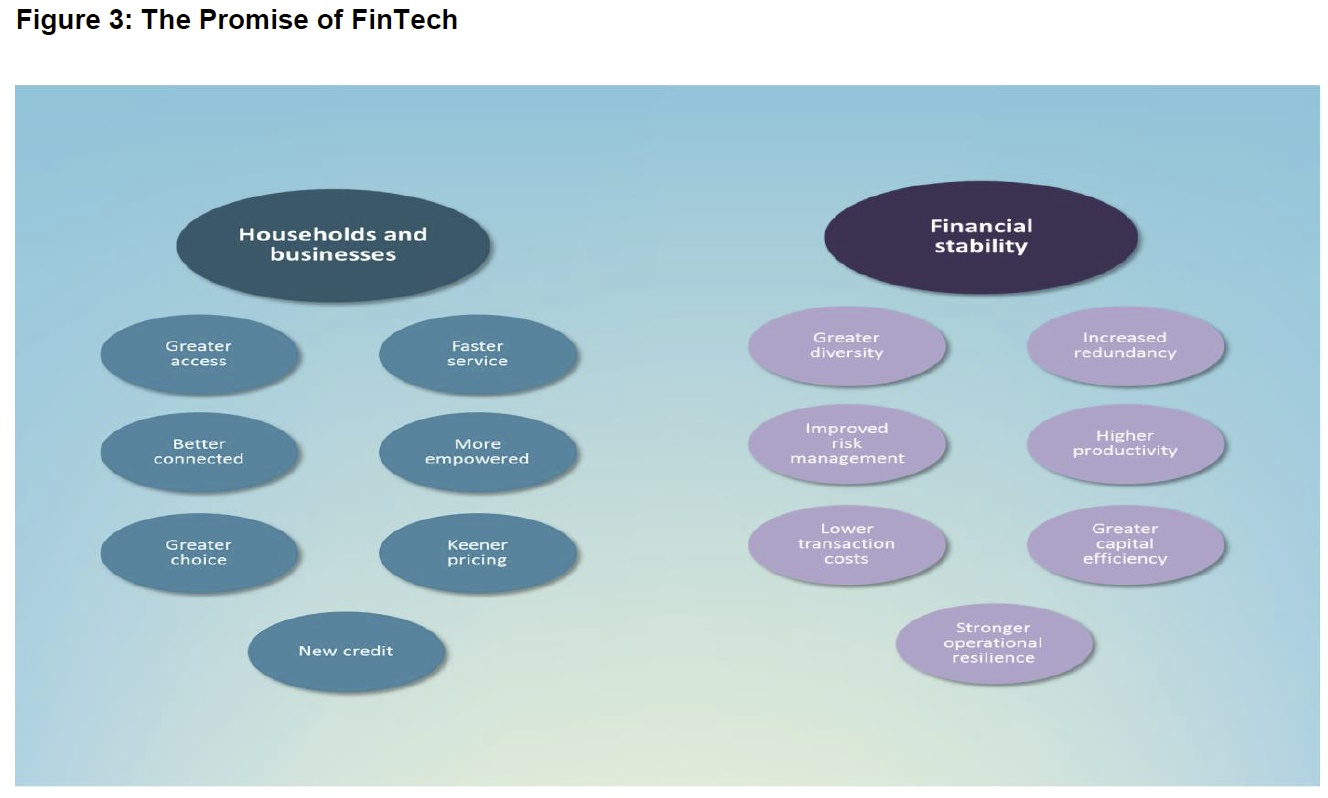

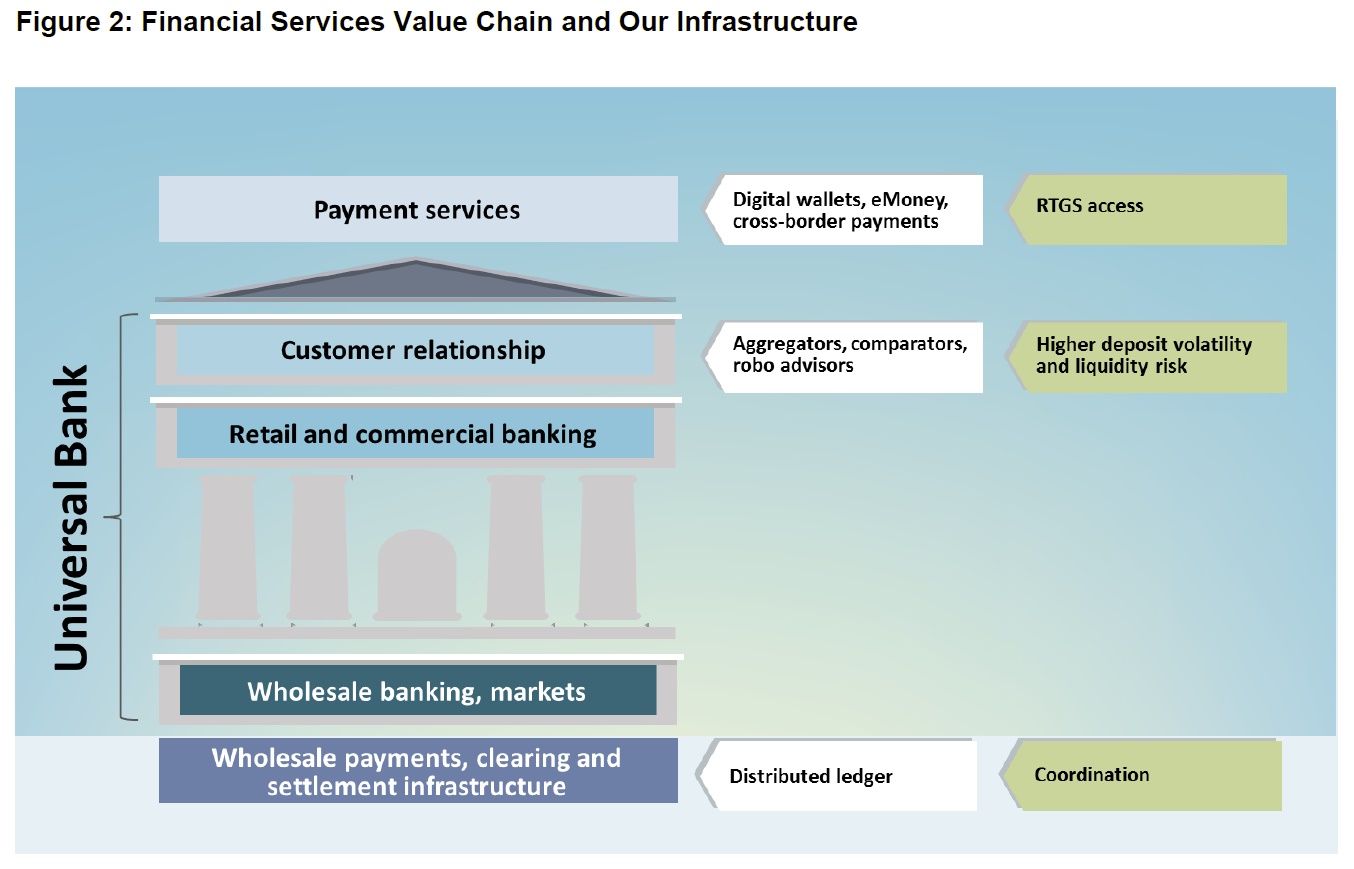

A second, related example is how the Bank is working to develop the financial system’s hard infrastructure to allow innovation to thrive while keeping the system safe.Specifically, the Bank is widening access to some of its systems to include PSPs in order to boost both competition and system resilience.

The UK has led the world in innovation in the wider payments ecosystem. And we are committed to keeping pace with customer demands for payments that are seamless, reliable, cheap, and ubiquitous. Our challenge is how to satisfy these expectations while maintaining a resilient payment systems infrastructure.That’s important because the Bank operates the UK’s high-value payment system ’RTGS’ which each day processes £1/2 trillion of payments on behalf of everyone from homeowners to global banks. Understandably, we have an extremely low tolerance for any threat to the integrity of the system’s “plumbing”.

Currently, only 52 institutions have settlement accounts in RTGS. Indirect users of the system typically access settlement via one of four agent banks. These indirect users include 1000 non-bank PSPs at the front-end of the financial services value chain. As they grow, some PSPs want to reduce their reliance on the systems, service levels, risk appetite and frankly goodwill of the very banks with whom they are competing.

The Bank has decided to widen access to RTGS to include non-bank PSPs in order to help them compete on a level playing field with banks. The Bank of England is now working with the FCA and HMT to make this a reality, and we will issue our new blueprint for RTGS in early May.

Coordinated Developments in Hard and Soft Infrastructure

My third example of the Bank’s efforts to realise FinTech’s promise is our work with industry to help coordinate advances in hard and soft infrastructure.New technologies could transform wholesale payments, clearing and settlement. In particular, distributed ledger technology could yield significant gains in the accuracy, efficiency and security of such processes, saving tens of billions of pounds of bank capital and significantly improving the resilience of the system.

Securities settlement seems particularly ripe for innovation. A typical settlement chain involves many intermediaries, making it comparatively slow and keeping operational risks high. Industry has begun to work together to determine how distributed ledger technologies could be used to solve these issues at scale.The Bank is participating in several related initiatives. To help distinguish distributed ledger’s potential from its hype, we have completed our own Proof of Concept. We are a member of Hyperledger along with private market participants and tech firms. And we will make our next generation RTGS compatible with settlement in a distributed ledger.

It is not clear, however, that that the only challenges are technological. Indeed, the FCA highlighted earlier this week that settlement times could also be cut using existing technologies. This requires market participants to change their collective practices as it takes more than one intermediary in a chain to compress settlement times.

Conclusion

FinTech’s promise springs from its potential to unbundle banking into its core functions of settling payments, performing maturity transformation, sharing risk and allocating capital.

This possibility is being realised by new entrants – payment service providers, aggregators and robo advisors, peer-to-peer lenders, and innovative trading platforms. And it is being influenced by incumbents who are adopting new technologies to reinforce the economies of scale and scope of their business models.

FinTech could deliver significant benefits to households and businesses across this country and across the world. FinTech can widen access to financial services and bring new sources of credit. It can connect customers better with their finances and empower them more in the process. And new technologies can deliver faster service, greater choice and keener pricing.

As it does, risks will evolve. Changes to customer loyalties could influence the stability of bank funding. New underwriting models could impact credit quality and even macroeconomic dynamics. New investing and risk management paradigms could affect market functioning.

At the same time, the resilience of the system could also be built, through greater diversity in provision of financial services as well as increased redundancy. A host of applications could reduce costs, improve capital efficiency and strengthen operational resilience.

The challenge for policymakers is to ensure that FinTech develops in a way that maximises the opportunities and minimises the risks for society.

We are ideally positioned to realise FinTech’s promise in the UK.The Bank will work with the market and other authorities to build the hard and soft infrastructure the system needs to support innovation and growth, consistent with the City’s best traditions.