FinTech’s true promise springs from its potential to unbundle banking into its core functions of: settling payments, performing maturity transformation, sharing risk and allocating capital. This possibility is being driven by new entrants – payment service providers, aggregators and robo advisors, peer-to-peer lenders, and innovative trading platforms. And it is being influenced by incumbents who are adopting new technologies in an effort to reinforce the economies of scale and scope of their business models.

In this process, systemic risks will evolve. Changes to customer loyalties could influence the stability of bank funding. New underwriting models could impact credit quality and even macroeconomic dynamics. New investing and risk management paradigms could affect market functioning. A host of applications and new infrastructure could reduce costs, probably improve capital efficiency and possibly create new critical economic functions.

The challenge for policymakers is to ensure that FinTech develops in a way that maximises the opportunities and minimises the risks for society. After all, the history of financial innovation is littered with examples that led to early booms, growing unintended consequences, and eventual busts.

Conduct regulators are in the lead in addressing regulatory issues posed by payment services innovations. This is both because, at least in advanced economies, FinTech payment service providers have not chosen to undertake banking activities and individual providers have not yet reached the scale that might be considered systemic.

Looking ahead, it is possible that virtual currencies and FinTech-based providers, particularly where they gain direct membership to central bank payment systems, could begin to displace traditional bank-based payment services and systems. Such diversification could be positive for stability; after all the existing tiered and highly concentrated system has created single point of failure risks. At the same time, regulators would need to monitor such changes for any new concentrations.

In this regard, with a view to such future proofing, the Digital Economy Bill in the UK proposes to extend the definition of a payment system beyond those that are inter-bank, to include any that become systemically important. If these are so designated by HMT, they would be supervised by the Bank. This would be akin to the recent recognition by HMT of Visa Europe and Link.

Changes to payments and customer relationships may have more fundamental implications for financial stability.

Specifically, while FinTech may make conventional banking more contestable, improving efficiency and customer choice, the opening up of the customer interface and payment services business, could, in time, signal the end of universal banking as we know it. If today’s universal banks lose the loyalty I saw on the Canadian prairie and instead have less stable funding and weaker, more arms-length client relationships, the volatility of their deposits and liquidity risk could increase. In addition, with weaker customer ties, cross-selling (my old preserve as a teller) could be less prevalent, hitting profitability. The system as a whole wouldn’t necessarily be riskier, but prudential standards and resolution regimes for banks may need to be adjusted.

The diversity in funding brought by market-based finance, as an alternative to retail banking, means that peer-to-peer lending has potential to provide some consumers and small businesses with affordable credit, when retail banks cannot. At the same time, this implies that borrowers in some segments may be placing increased reliance on this source of funding. How stable this funding will prove through-the-cycle is not yet clear, as the sector’s underwriting standards, and lenders’ tolerance to losses, have not been tested by a downturn.

Due to its small scale and business models, the P2P lending sector does not, for now, appear to pose material systemic risks. That said, as a general rule, it always pays to monitor closely fast-growing sources of credit for slippages in underwriting standards and the promotion of excessive borrowing. Moreover, it is not clear the extent to which P2P lending can grow without business models evolving in ways that introduce conventional risks, including maturity transformation, leverage and liquidity mismatch, or through the use of originate and distribute models such as those seen in securitisation in the 2000s. Were these changes to occur, regulators would be expected to address such emerging vulnerabilities.

In wholesale banking and markets, robo-advice and risk management algorithms may lead to excess volatility or increase pro-cyclicality as a result of herding, particularly if the underlying algorithms are overly sensitive to price movements or highly correlated. Similarly, although algorithmic traders have become a more important source of market liquidity in many important financial markets, they tend to be more active during periods of low volatility giving an illusion of plentiful liquidity that may subsequently be withdrawn during periods of market disruption when it is needed most.

FinTech innovations, such as distributed ledgers, are being trialled for use within, or as a substitute to, existing wholesale payment, clearing and settlement infrastructure, will need to meet the highest standards of resilience, reliability, privacy and scalability.

For all financial firms, the advent of FinTech materially changes operational and cyber risks. Regulators need to be alert to new single point of failure risks such as if banks come to rely on common hosts of online banking or providers of cloud computing services.

In recent years, the cyber threat to the system has grown as financial institutions have become more reliant on interconnected IT systems. As the FinTech future envisages the sharing of data across a wider set of parties, coupled with greater speed and automaticity in executing transactions, the challenges around protecting data and the integrity of the system are likely to increase. One sign of this is a growing preoccupation in the insurance industry with how best to underwrite such risks.

Recognising the vital importance of learning from international experience, in late 2016 the G20 called upon the FSB to stock-take existing cyber security regulation, as a basis for developing best practices in the medium-term.

While only private sector ingenuity will make these gains possible, authorities have essential, supporting roles in reinforcing them and managing the associated risks to financial stability. To help realise FinTech’s promise, we should refresh our supervisory approaches in a few ways.

First, regulatory sandboxes can allow businesses to test innovative products, services, business models and delivery mechanisms in a live environment and with proportionate regulatory requirements. This supports innovation and learning by developers and regulators. The FCA was an early mover launching Project Innovate in 2014.21 The G20 might consider the extent to which such approaches should be adopted more widely.

Second, existing authorisation processes can also be adapted to ensure they do not unnecessarily block new business models and approaches. This is why in the UK, the PRA and FCA now work closely with all firms seeking new authorisation as banks.

Third, the Bank of England is expanding access to central bank money to non-bank payments service providers (“PSPs”). Allowing access to the Bank’s Real Time Gross Settlement System allows PSPs to compete directly with banks, and so supports innovation, competition and financial stability.

Fourth, a number of authorities, including the Bank of England with its FinTech accelerator, are developing Proofs of Concepts with new enabling technologies from machine learning to distributed ledgers. And, to explore what could be genuinely new under the sun, we are researching the policy and technical issues posed by Central Bank Digital Currencies. On some levels this is appealing; people would have direct access to the ultimate risk-free asset. In the extreme, however, it could fundamentally reshape banking including by sharply increasing liquidity risk for traditional banks

This last point underscores that, in order for FinTech’s potential to be realised, authorities must manage its impact on financial stability. On the positive side, FinTech could reduce systemic risks by delivering a more diverse and resilient system where incumbents and new entrants compete along the value chain. At the same time, some innovations could generate systemic risks through increased interconnectedness and complexity, greater herding and liquidity risks, more intense operational risk and opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

As those risks emerge, authorities can be expected to pursue a more intense focus on the regulatory perimeter, more dynamic settings of prudential requirements, a broader commitment to resolution regimes, and a more disciplined management of operational and cyber risks. And we will be alert to potential impacts on the existing core of the system, including through business model analysis and market impact assessments.

By enabling technologies and managing risks, we can help create a new financial system for a new age… under the same sun.

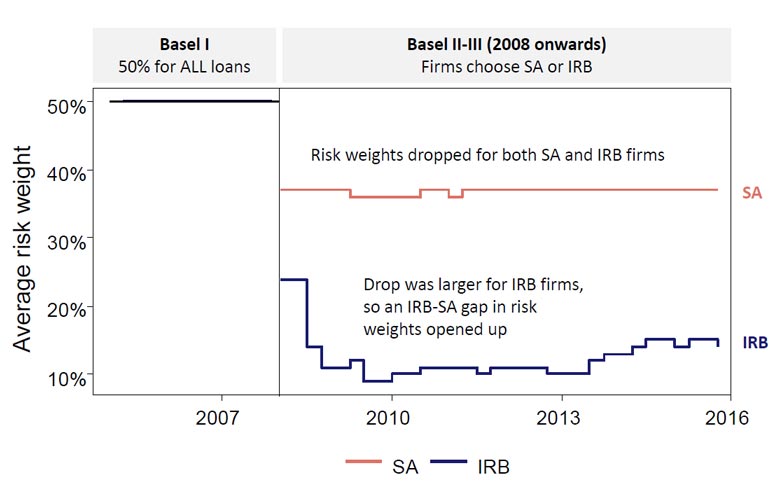

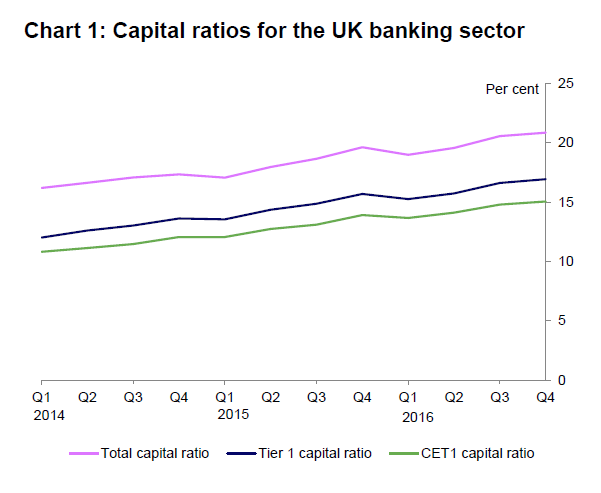

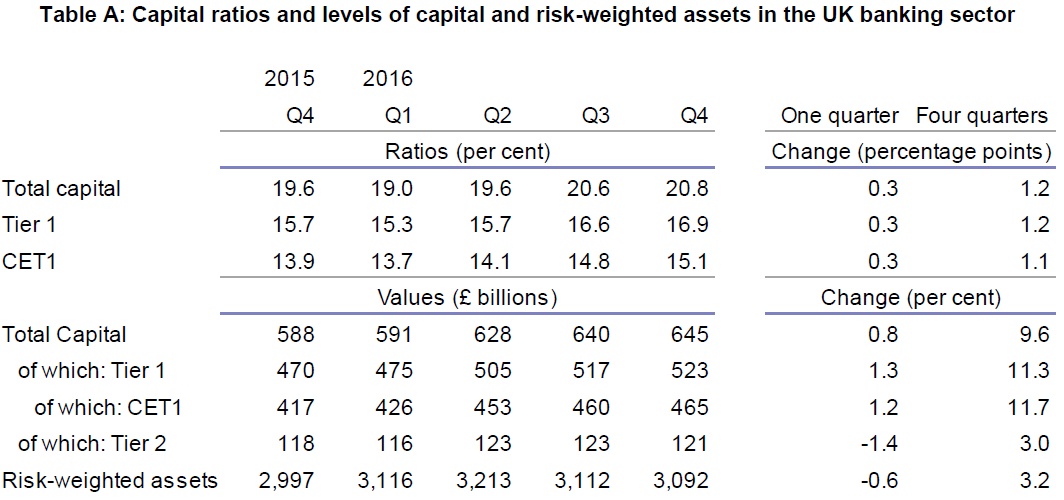

The quarterly increase was driven by small movements in both the level of CET1 capital (increase) and in the level of total risk-weighted assets (decrease).

The quarterly increase was driven by small movements in both the level of CET1 capital (increase) and in the level of total risk-weighted assets (decrease). The reduction in risk-weighted assets was driven by small decreases in most risk categories.

The reduction in risk-weighted assets was driven by small decreases in most risk categories.