Household debt is high and rising in many advanced and emerging market economies. Quantitative easing has been a “volatility stabiliser” in financial markets and when it is removed or reversed, it is not clear how the market will react. We are in uncharted territory! Yet, monetary policy normalisation is essential for rebuilding policy space, creating room for countercyclical policy.

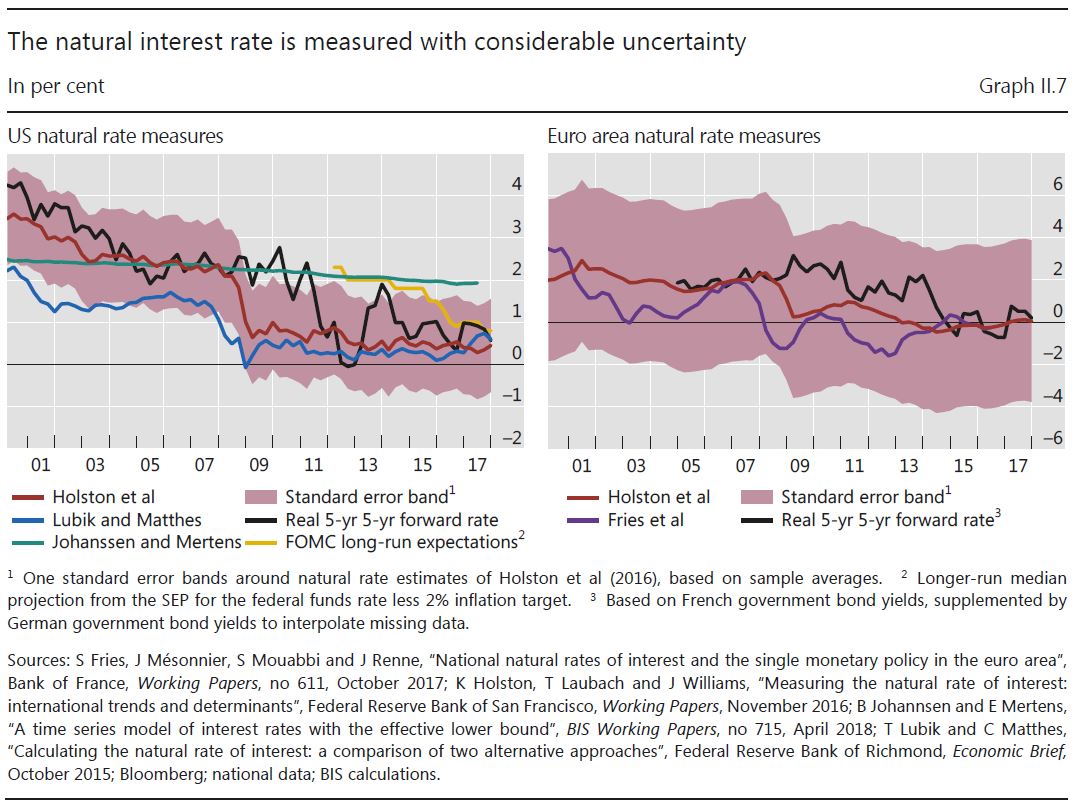

Monetary policy normalisation in the major advanced economies is making uneven progress, reflecting different stages of recovery from the GFC. The Federal Reserve has begun unwinding its asset holdings by capping reinvestments and has increased policy rates. The ECB has scaled back its large-scale asset purchases, with a likely halt of net purchases by end-year. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan is continuing with its purchases and has not communicated any plan for exiting.

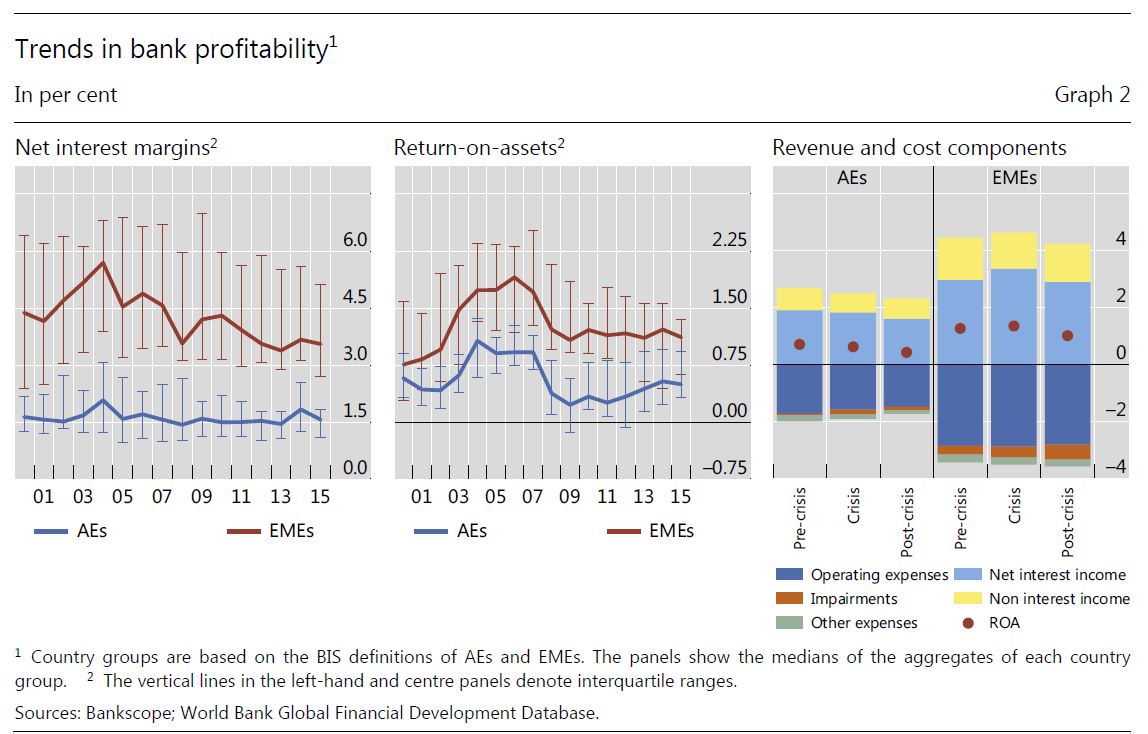

The ongoing unwinding of accommodative monetary policy in core advanced economies is a welcome step. It is a sign of success as economies have been brought back to growth and inflation rates back towards target levels. Monetary policy normalisation is essential for rebuilding policy space, creating room for countercyclical policy. Moreover, it can help restrain debt accumulation and reduce the risk of financial vulnerabilities emerging.

But there are also significant challenges. The starting point of the ongoing normalisation is unprecedented, and there are extreme uncertainties involved. The path ahead for central banks is quite narrow, with pitfalls on either side. Central banks will need to strike and maintain a delicate balance between competing considerations. This includes, in particular, the challenge of achieving their inflation objectives while avoiding the risk of encouraging the build-up of financial vulnerabilities.

Central banks have prepared and implemented normalisation steps very carefully. Policy normalisation has been very gradual and highly predictable. Central banks have placed great emphasis on telegraphing their policy steps through extensive use of forward guidance. As a consequence, major financial and economic ructions have so far been avoided. In this regard, the increased resilience of the financial sector as a consequence of the wide regulatory and supervisory reforms undertaken since 2009 has also helped.

That said, there are still plenty of risks out there.

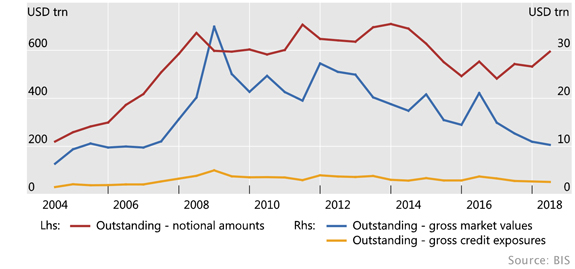

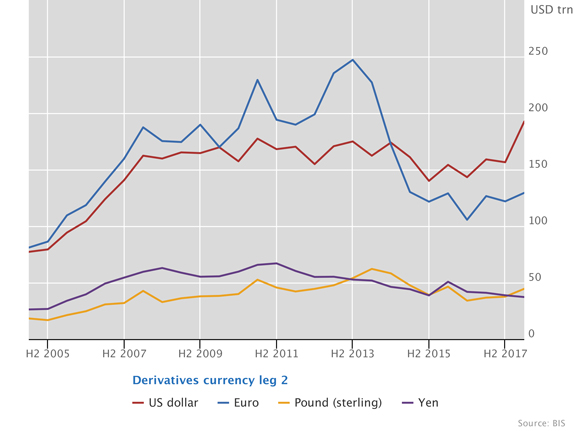

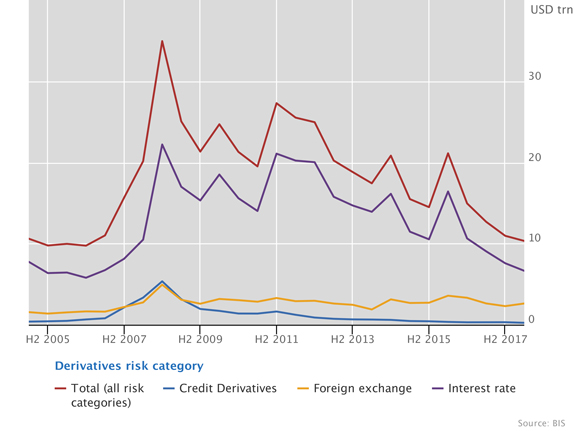

First, central banks are not in control of the entire yield curve and of the behaviour of risk premia. Investor sentiment and expectations are key factors determining these variables. An abrupt repricing in financial markets may prompt an outsize revision of the expected level of risk-free interest rates or a decompression in risk premia. Such a snapback could be amplified by market dynamics and have adverse macroeconomic consequences. It could also be accompanied by sudden sharp exchange rate fluctuations and spill across borders, with broader repercussions globally.

Second, many intermediaries are in uncharted waters. Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have grown faster than actively managed mutual funds over the past decade, and needless to say, they have brought very important benefits to bond markets, among other factors, by enhancing the depth of such markets and making possible new ways of financing for many sovereigns and corporations. ETFs are especially popular among equity investors, but they have also gained importance among bond investors.

They have attracted investors because they charge lower fees than traditional mutual funds, which has proved to be an important advantage in the ultra-low interest rate environment. Moreover, they promise liquidity on an intraday basis, hence more immediately than mutual funds, which provide it only daily.

Such promise of intraday liquidity is, however, a double-edged sword. As soon as ETF investors are confronted with negative news or observe an unexpected fall in the underlying asset price, they can run – that is, sell their ETF shares immediately – adding to the downward pressure on market prices. As equity markets become choppier, we will need to be on the look-out for ETFs possibly accentuating the volatility of the underlying asset market.

Currently, bond ETFs are still small compared with bond mutual funds in terms of their assets under management. However, as the market share of ETFs increases, their impact on market price dynamics will also increase. Moreover, they have yet to be tested in periods of high interest rates.

More generally, investors may face unforeseen risks – in particular, unforeseen dry-ups in liquidity. As I mentioned earlier, the growing size of the asset management industry may have increased the risk of liquidity illusion: market liquidity seems to be ample in normal times, but dries up quickly during market stress. Asset managers and institutional investors do not have strong incentives to play a market-making role when asset prices fall due to large order imbalances. Moreover, precisely when asset prices fall, asset managers often face redemptions by investors. This is especially true for bond funds investing in relatively illiquid corporate or EME bonds. Therefore, when market sentiment shifts adversely, investors may find it more difficult than in the past to liquidate bond holdings.

Central banks’ asset purchase programmes may also have contributed to liquidity illusion in some bond markets. Such programmes have led to portfolio rebalancing by investors from safe government debt towards riskier bonds, including EME bond markets, making them look more liquid. However, such liquidity may disappear in the event of market turbulence. Also, as advanced economy central banks unwind their asset purchase programmes and increase policy rates, investors may choose to rebalance from riskier bonds back to safe government bonds. This can widen spreads of corporate and EME bonds.

Moreover, asset managers’ investment strategies can collectively increase financial market volatility. A key source of risk here is asset managers’ “herding” in illiquid bond markets. Fund managers often claim that their performance is evaluated over horizons as long as three to five years. Nevertheless, they tend to have a strong aversion to underperforming over short periods against industry peers. This can lead to increased risk-taking and highly correlated investment strategies across asset managers. For example, recent BIS research shows that EME bond fund investors tend to redeem funds at the same time. Moreover, the fund managers of the so-called actively managed EME bond funds are found to closely follow a small number of benchmarks (a practice known as “benchmark hugging”).

Third, the fundamentals of many economies are not what they should be while at the same time there seems to be less political appetite for prudent macro policies. High and rising sovereign debt relative to GDP in many advanced economies has increased the sensitivity of investors to the perceived ability and willingness of governments to ensure debt sustainability. Sovereign debt in EMEs is considerably lower than in advanced economies on average, but corporate leverage has continued to rise and has reached record levels in many EMEs.

Also, household debt is high and rising in many advanced and emerging market economies. In addition, a large amount of EME foreign currency debt matures over the next few years, and large current account and fiscal deficits in some EMEs could induce global investors to take a more cautious stance. Tightening global financial conditions and EME currency depreciation may increase the sensitivity of investors to these vulnerabilities.

Fourth, other factors may augment the spillover effects from unwinding unconventional monetary policy. Expansionary fiscal policy in some core advanced economies may further push up interest rates, by increasing government bond supply and aggregate demand in already-overheating economies. Trade tensions have started to darken the growth prospects and balance of payments outlook of many countries. Such tensions also have repercussions on exchange rates and corporate debt sustainability. Heightened geopolitical risks should not be ignored either. The sharp corrections in advanced economy and EME equity markets alike in October 2018 are generally attributed to both aggravating trade tensions and geopolitical risks.

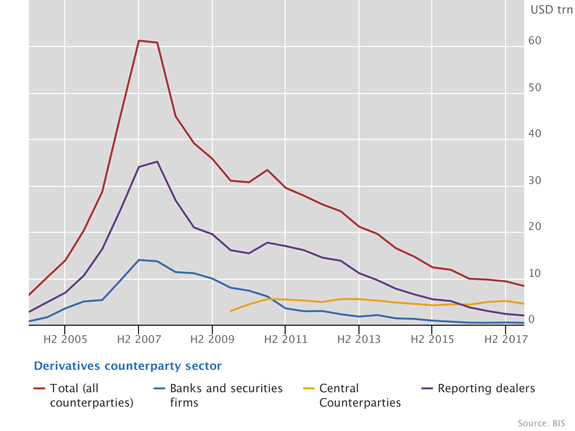

Fifth, there is much uncertainty about how investors will react to monetary policy normalisation. Quantitative easing has been a “volatility stabiliser” in financial markets. Thus, when it is removed or reversed, it is not clear how the market will react. Market segments of particular concern are high-yield bonds and EME corporate bonds. As I pointed out a moment ago, liquidity tends to dry up more easily in these markets. Knowing this, asset managers may try to rebalance their portfolios by deleveraging more liquid surrogates first, which creates an avenue for contagion to other markets.

“Tourist investors” are another source of concern. For example, in contrast to “dedicated” bond funds, which follow specific benchmarks relatively closely, “crossover” funds have benchmarks but deviate from them and cross over to riskier asset classes such as EME bonds and high-yield corporate bonds in search of yield. Crossover funds are not new, but they have gained prominence recently. They include high-yield, high-risk bonds in their portfolio by arguing that the extra return from such investments is high enough to compensate for their risk. They are likely to underprice risks when markets are calm, but overprice risks when markets become volatile. They are, indeed, very responsive to interest rate and exchange rate surprises and tend to pull out suddenly from risky investments.

Finally, significant allocations by global asset managers to domestic currency bond markets, in particular to EME local currency sovereign bonds, have generated new challenges. After the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98, many emerging Asian economies made concerted efforts to develop their local currency bond markets. This was a welcome development, overcoming “original sin”, a term coined by Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann in 1999 for the inability of developing countries to borrow in their domestic currency. By relying on long-term local currency bonds instead of short-term foreign currency loans, many Asian EME borrowers were able to avoid currency mismatch and reduce rollover risk. In addition, over the past several years, the average maturity of EME local currency bonds has increased overall.

However, as the share of foreign investment in EME local currency bond markets has increased, currency and rollover risks have been replaced by duration risk. The effective duration of an investment measures the sensitivity of the investment return to the change in the bond yield. Recent BIS research shows that EME local currency bond yields tend to increase in tandem with domestic currency depreciation. This can make returns of EME local currency bond investors, whose investment performance is measured in the US dollar (or the euro), extremely volatile. As an analogy, incorporating exchange rate consideration is similar to viewing temperatures with and without a wind chill factor.

This suggests that the exchange rate response to capital flows might not stabilise economies as textbooks predict: it might instead lead to procyclical non-linear adjustments. Exchange rate changes can drive capital in- and outflows via the so called risk-taking channel of exchange rates.

The core mechanism of the risk-taking channel works as follows. In the presence of currency mismatch, a weaker dollar flatters the balance sheet of the EME’s dollar borrowers. This induces creditors (either global banks or global bond investors) to extend more credit. As a consequence, a weaker dollar goes hand in hand with reduced tail risks and increased EME borrowing. However, when the dollar strengthens, these relationships go into reverse.

Policy implications

Monetary policy normalisation by major advanced economies, escalating trade tensions, heightened geopolitical risks and new forms of financial intermediation all pose challenges going forward for both advanced and emerging market economies. How can policymakers rise to these challenges?

Inadequate growth-enhancing structural policies have been a major deficiency over the past years. Such policies would facilitate the treatment of overindebtedness. In contrast to expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, which boost both debt and output, growth-enhancing structural reforms would primarily boost output, thus reducing debt burdens relative to incomes. Moreover, by improving the supply side of the economy, they would contain inflationary pressures. And, if sufficiently broad in scope, they would have positive distributional effects, reducing income inequality.

Advanced economies should be mindful of spillovers, also because they can mutate into spillbacks. During phases in which interest rates remain low in the main international funding currencies, especially the US dollar, EMEs tend to benefit from easy financial conditions. These effects then play out in reverse once interest rates rise. A reversal could occur, for instance, if bond yields snapped back in core advanced economies, and especially if this went hand in hand with US dollar appreciation. A clear case in point is the change in financial conditions experienced by EMEs since the US dollar started appreciating in the first quarter of 2018.

Global spillovers can also have implications for the core economies. The collective size of the countries exposed to the spillovers suggests that what happens there could also have significant financial and macroeconomic effects in the originating economies. At a minimum, such spillbacks argue for enlightened self-interest in the core economies, consistent with domestic mandates. This is an additional policy dimension that complicates the calibration of the normalisation and that deserves close attention.

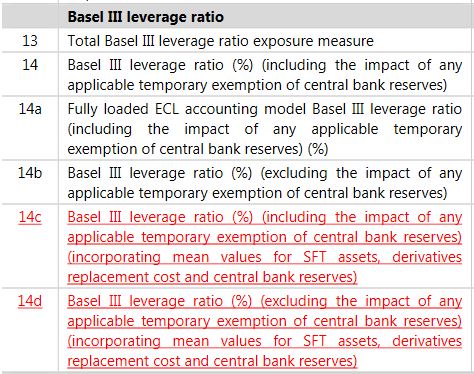

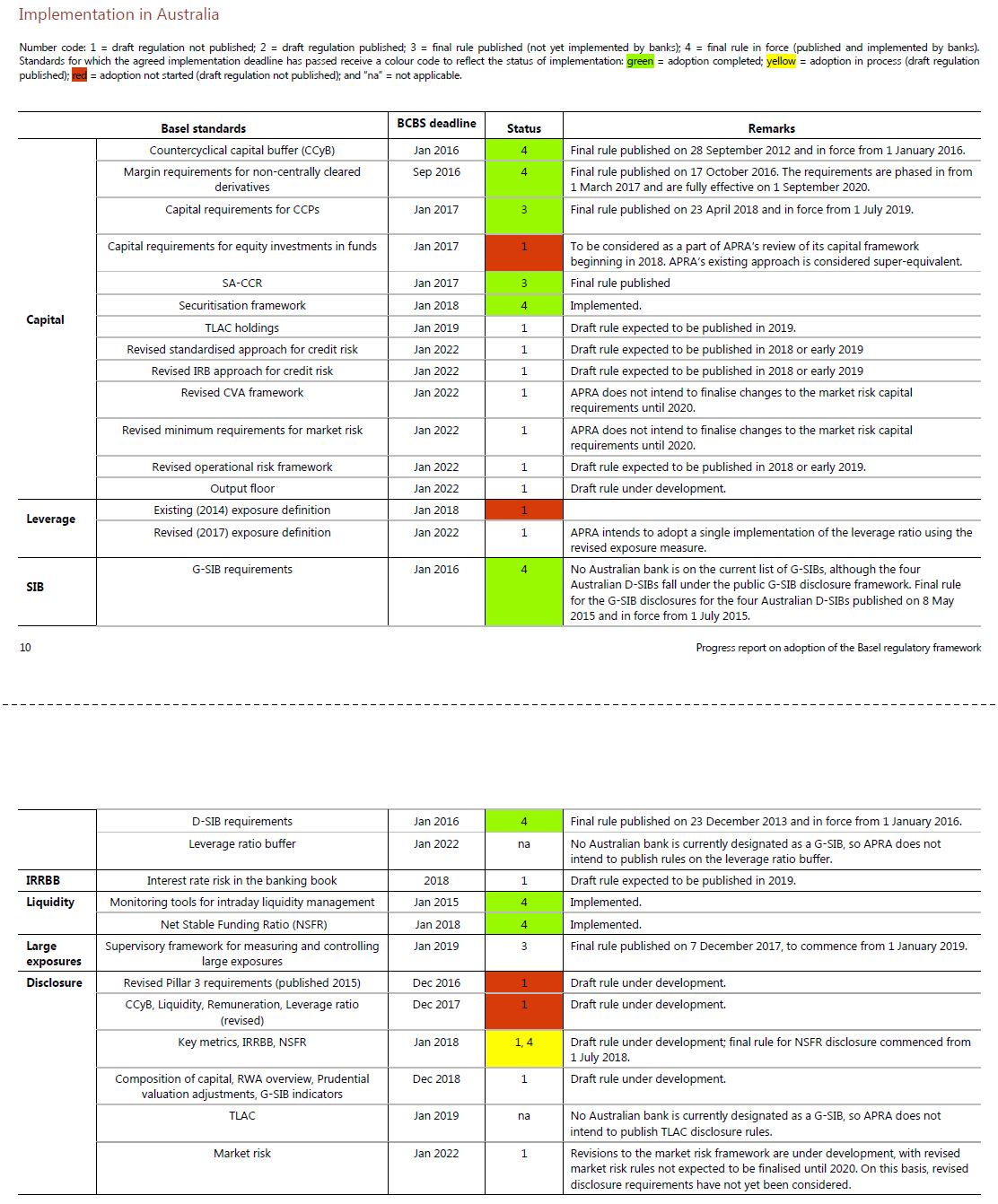

Financial reforms should be fully implemented. If enforced in a timely and consistent manner, these reforms will contribute to a much stronger banking system. Indeed, the Basel Committee’s Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme has found that its members have put in place most of the major elements of Basel III. But implementation delays remain. It is important to attain full, timely and consistent implementation of all the rules. This would improve the resilience of banks and the banking system. It is also necessary for attaining a level playing field and limiting the room for regulatory arbitrage.

For EMEs, keeping one’s house in order is paramount because there is no room for poor fundamentals during tightening global financial conditions. EMEs may nevertheless face capital outflows, and their currencies may depreciate abruptly, which would trigger further capital outflows. In such instances, EME authorities must be prepared to respond forcefully. They should consider combining interest rate adjustments with other policy options such as FX intervention. And they should consider using the IMF’s contingent lending programmes.

At the same time, EMEs should not disregard non-orthodox policies to deal with stock adjustment. If a large amount of foreign capital has flowed into domestic markets and threatens to flow out quickly, the central bank can use its balance sheet to stabilise markets. As an example, the Bank of Mexico has in the past swapped long-term securities for short-term securities via auctions. This was done because such long-term instruments were not in the hands of strong investors, and there was market demand for short-term securities. This policy stabilised conditions in peso-denominated bond markets.

Finally, policymakers need to better understand asset managers’ behaviour in stress scenarios and to develop appropriate policy responses. One key question for policymakers is how to dispel liquidity illusion and to support robust market liquidity. Market-makers, asset managers and other investors would need to take steps to strengthen their liquidity risk management. Policymakers can also provide them with incentives to maintain robust liquidity during normal times to weather liquidity strains in bad times – for example, by encouraging regular liquidity stress tests.