Are Some Banks Cooking The Books?

We look at the REPO market and how it may being used to cook the books, as highlighted by the Bank for International Settlements.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

We look at the REPO market and how it may being used to cook the books, as highlighted by the Bank for International Settlements.

The Banker’s Bank, in their annual report confirmed that there is evidence that some banks are massaging their quarter end results to fit within certain capital ratios using Repurchase Agreements (REPO’s). So Central banks’ own financial operations with bank counterparties are making a mockery of any macroprudential regulation attempts by central banks … plain alarming!

Several years ago we showed how the Fed’s then-new Reverse Repo operation had quickly transformed into nothing more than a quarter-end “window dressing” operation for major banks, seeking to make their balance sheets appear healthier and more stable for regulatory purposes.

As we described in article such as “What Just Happened In Today’s “Crazy” And Biggest Ever “Window-Dressing” Reverse Repo?”,Window Dressing On, Window Dressing Off… Amounting To $140 Billion In Two Days”, “Month-End Window Dressing Sends Fed Reverse Repo Usage To $208 Billion: Second Highest Ever“, “WTF Chart Of The Day: “Holy $340 Billion In Quarter-End Window Dressing, Batman“, “Record $189 Billion Injected Into Market From “Window Dressing” Reverse Repo Unwind” and so on, we showed how banks were purposefully making their balance sheets appear better than they really with the aid of short-term Fed facilities for quarter-end regulatory purposes, a trick that gained prominence first nearly a decade ago with the infamous Lehman “Repo 105.”

And this is a snapshot of what the reverse-repo usage looked like back in late 2014:

Today, in its latest Annual Economic Report, some 4 years after our original allegations, the Bank for International Settlements has confirmed that banks may indeed be “disguising” their borrowings “in a way similar to that used by Lehman Brothers” as debt ratios fall within limits imposed by regulators just four times a year, thank to the use of repo arrangements.

For those unfamiliar, the BIS explains that window-dressing refers to the practice of adjusting balance sheets around regular reporting dates, such as year- or quarter-ends and notes that “window-dressing can reflect attempts to optimise a firm’s profit and loss for taxation purposes.”

For banks, however, it may also reflect responses to regulatory requirements, especially if combined with end-period reporting. One example is the Basel III leverage ratio. This ratio is reported based on quarter-end figures in some jurisdictions, but is calculated based on daily averages during the quarter in others. The former case can provide strong incentives to compress exposures around regulatory reporting dates – particularly at year-ends, when incentives are reinforced by other factors (eg taxation).”

But why repo? Because, as a form of collateralised borrowing, repos allow banks to obtain short-term funding against some of their assets – a balance sheet-expanding operation. The cash received can then be onlent via reverse repos, and the corresponding collateral may be used for further borrowing. At quarter-ends, banks can reverse the increase in their balance sheet by closing part of their reverse repo contracts and using the cash thus obtained to repay repos. This compression raises their reported leverage ratio, massaging their assets lower, and boosting leverage ratios, allowing banks to report them as being in line with regulatory requirements.

So what did the BIS finally find? Here is the condemning punchline which was obvious to most back in 2014:

“The data indicate that window-dressing in repo markets is material”

The report continues:

Data from U.S. money market mutual funds point to pronounced cyclical patterns in banks’ U.S. dollar repo borrowing, especially for jurisdictions with leverage ratio reporting based on quarter-end figures (Graph III.A, left-hand panel). Since early 2015, with the beginning of Basel III leverage ratio disclosure, the amplitude of swings in euro area banks’ repo volumes has been rising – with total contractions by major banks up from about $35 billion to more than $145 billion at year-ends. Banks’ temporary withdrawal from repo markets is also apparent from MMMFs’ increased quarter-end presence in the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo (RRP) operations, which allows them to place excess cash (right-hand panel, black line).

This is problematic because this central-bank endorsed mechanism “reduces the prudential usefulness of the leverage ratio, which may end up being met only four times a year.” Furthermore, the BIS alleged that in addition to its negative effects on financial stability, the use of repos to game the requirement hinders access to the market for those who need it at quarter end and obstructs monetary policy implementation.

This is hardly a new development, and as we explained in 2014, one particular bank was notorious for its use of similar sleight of hand: as Bloomberg writes, the use of repo borrowings is similar to a “Lehman-style trick” in which the doomed bank used repos to disguise its borrowings “before it imploded in 2008 in the biggest-ever U.S. bankruptcy.”

The collapse prompted regulators to close an accounting loophole the firm had wriggled through to mask its debts and to introduce a leverage ratio globally.

How ironic, then, that it is central banks’ own financial operations with bank counterparties, that make a mockery of any macroprudential regulation attempts by central banks, and effectively exacerbate the problems in the financial system by implicitly allowing banks to continue masking the true extent of their debt.

An interesting perspective on crypto-currencies from an op-ed by Mr Agustín Carstens, General Manager of the BIS. He says that the short experience of cryptocurrencies shows that technology, however sophisticated, is a poor substitute for hard-earned trust in sound institutions. Perhaps not an unsurprising stance from the central bankers’ banker! As we highlighted yesterday, some central banks are now exploring alternatives via CBDC’s.

How to preserve trust in financial transactions is a tricky business in our digital age. With new cryptocurrencies proliferating, it’s as important to educate the public about good money as it is to build defences against fake news, online identity theft and Twitter bots. Conjuring up new cryptocurrencies is the latest chapter in a long story of attempts to invent new money, as fortune seekers have tried to make a quick buck. It has become the alchemy of the age of innovation, with the promise of magically transforming everyday substances (electricity, in this case) into gold (or at least euros).

Many cryptocurrencies are ultimately get-rich-quick schemes. They should not be conflated with the sovereign currencies and established payment systems that have stood the test of time. What makes currencies credible is trust in the issuing institution, and successful central banks have a proven record of earning this public trust. The short experience of cryptocurrencies shows that technology, however sophisticated, is a poor substitute for hard-earned trust in sound institutions. We will explain this concept further in a special section of our annual report on 17 June.

Recent episodes show how private cryptocurrencies struggle to earn public trust. Cases of fraud and misappropriation abound. Above all, the technology behind cryptocurrencies makes them inefficient and certainly less effective than the digital payment systems already in place. Let me highlight three aspects.

First, the highly volatile valuations of cryptocurrencies conflict with the stable monetary values that must underpin any system of transactions which sustains economic activity. Over the last two decades, consumer price inflation in advanced economies averaged 1.8%. In contrast, over the last three months, the five largest cryptocurrencies have on average lost 21% of their value against the US dollar.

Second, the many cases of fraud and theft show that cryptocurrencies are prone to a trust deficit. Given the size and unwieldiness of the distributed ledgers that act as a register of crypto-holdings, consumers and retail investors in fact access their “money” via third parties (crypto-wallet providers or crypto-exchanges.) Ironically, investors who opted for cryptocurrencies because they distrusted banks have thus wound up dealing with entirely unregulated intermediaries that have in many cases turned out to be fraudulent or have themselves fallen victim to hackers.

Third, there are fundamental conceptual problems with cryptocurrencies. Making each and every user download and verify the history of each and every transaction ever made is just not an efficient way to conduct transactions. This cumbersome operational setup means there are hard limits on how many, and how quickly, transactions are processed. Cryptocurrencies therefore cannot compete with mainstream payment systems, especially during peak times. This leads to congestion, transaction fees soar, and very long delays result.

In the end, one has to ask if cryptocurrencies are an improvement compared with current means of payment. Technological advances can mitigate some of the shortcomings of existing cryptocurrencies, but institution-free technology is unlikely ever to remedy the fundamental problem of recreating trust from a fragmented system of unregulated, self-interested actors. In particular, in a decentralised network of users, nobody has the incentive to stabilise the currency in times of crisis. This can make the whole system unstable at any given point in time.

Admittedly, there are also sobering examples of sovereign monies failing, mostly when public trust broke down – even in recent times. But on the whole, recent decades can be seen as a historically rare period of monetary stability, underpinned by independent central banks.

The technology behind cryptocurrencies could be used in other interesting ways, however. Central banks have long championed the use of new payment technologies – as long as they prove socially useful – in the interests of increased efficiency. One should also note that digital central bank money is not new: it has been quietly enabling some of the most significant innovations in financial plumbing for the last 20 years.

Currently, central banks around the world are working on systems for retail payments that will allow instant transfers, anytime and anywhere. They are also actively testing the distributed ledger technology underlying cryptocurrencies – not as a substitute for the current system, but to build on it. Even in this digital age, trust in the issuing institution matters and will continue to underpin currencies. Central banks, for their part, will have to continue earning that public trust by closely guarding their currency’s value.

Welcome to the Property Imperative Weekly to 14 April 2018. We review the latest property and finance news.

There is a massive amount to cover in this week’s review of property and finance news, so we will dive straight in.

There is a massive amount to cover in this week’s review of property and finance news, so we will dive straight in.

CoreLogic says that final auction results for last week showed that 1,839 residential homes were taken to auction with a 62.8 per cent final auction clearance rate, down from 64.8 per cent over the previous week. Auction volumes rose across Melbourne with 723 auctions held and 68.2 per cent selling. There were a total of 795 Sydney auctions last week, but the higher volumes saw the final clearance rate weaken with 62.9 per cent of auctions successful, down on the 67.9 per cent the week prior. All of the remaining auction markets saw a rise in activity last week; clearance rates however returned varied results week-on-week, with Adelaide Brisbane and Perth showing an improvement across the higher volumes while Canberra and Tasmania both recorded lower clearance rates. Across the non-capital city regions, the highest clearance rate was recorded across the Hunter region, with 72.5 per cent of the 45 auctions successful.

This week, CoreLogic is currently tracking 1,690 capital city auctions and as usual, Melbourne and Sydney are the two busiest capital city auction markets, with 795 and 678 homes scheduled to go to auction. Auction activity is expected to be lower week-on week across each of the smaller auction markets

Two points to make. First is a slowing market, more homes will be sold privately, rather than via auctions, and this is clearly happening now, and second, we discussed in detail the vagaries of the auction clearance reporting in our separate blog, so check that out if you want to understand more about how reliable these figures are.

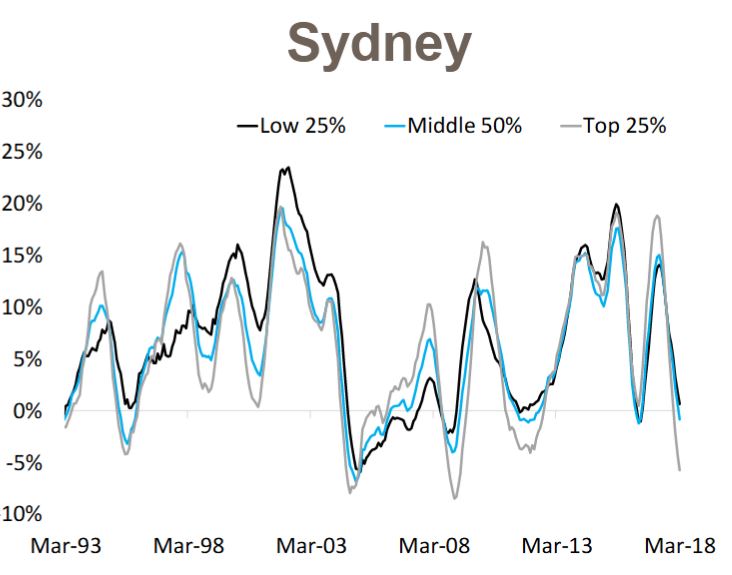

Home prices slipped a little this past week according to the CoreLogic index, but their analysis also confirmed what we are seeing, namely that more expensive properties are falling the most. In fact, values in the most expensive 25% of the property market are falling the fastest, whereas values for the most affordable 25% have actually risen in value.

Their analysis shows that over the March 2018 quarter, national data shows that dwelling values were down by 0.5%, however digging below the surface reveals the modest fall in values was confined to the most expensive quarter of the market. The most affordable properties increased in value by +0.7% compared to a +0.3% increase across the middle market and a -1.1% decline across the most expensive properties.

But looking at the details by location, in Sydney, over the past 12 months, the most expensive properties have recorded the largest value falls (-5.7%) followed by the middle market (-0.9%) and the most affordable market managed some moderate growth (+0.6%).

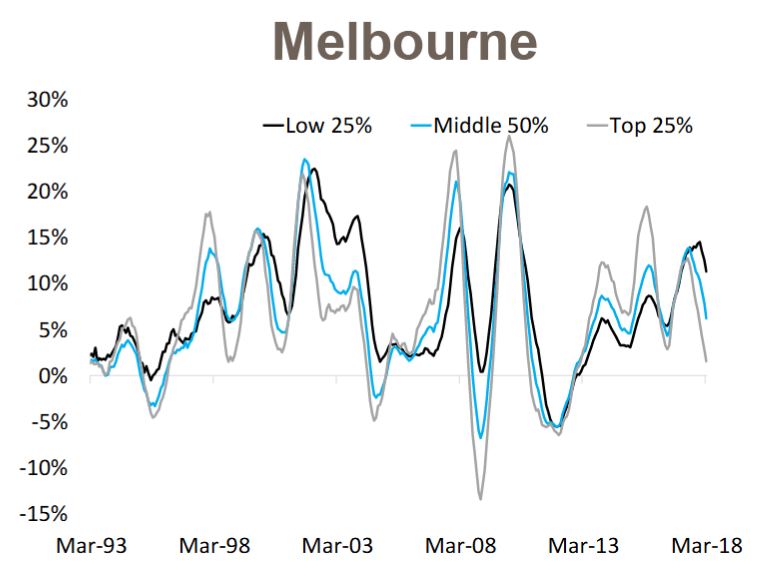

Compare that with Melbourne where values have increased over the past year across each segment of the market, with the most moderate increases recorded across the most expensive segment (+1.6%), then the middle 50% (+6.2%) while the most affordable suburbs have recorded double-digit growth (+11.3%)

Compare that with Melbourne where values have increased over the past year across each segment of the market, with the most moderate increases recorded across the most expensive segment (+1.6%), then the middle 50% (+6.2%) while the most affordable suburbs have recorded double-digit growth (+11.3%)

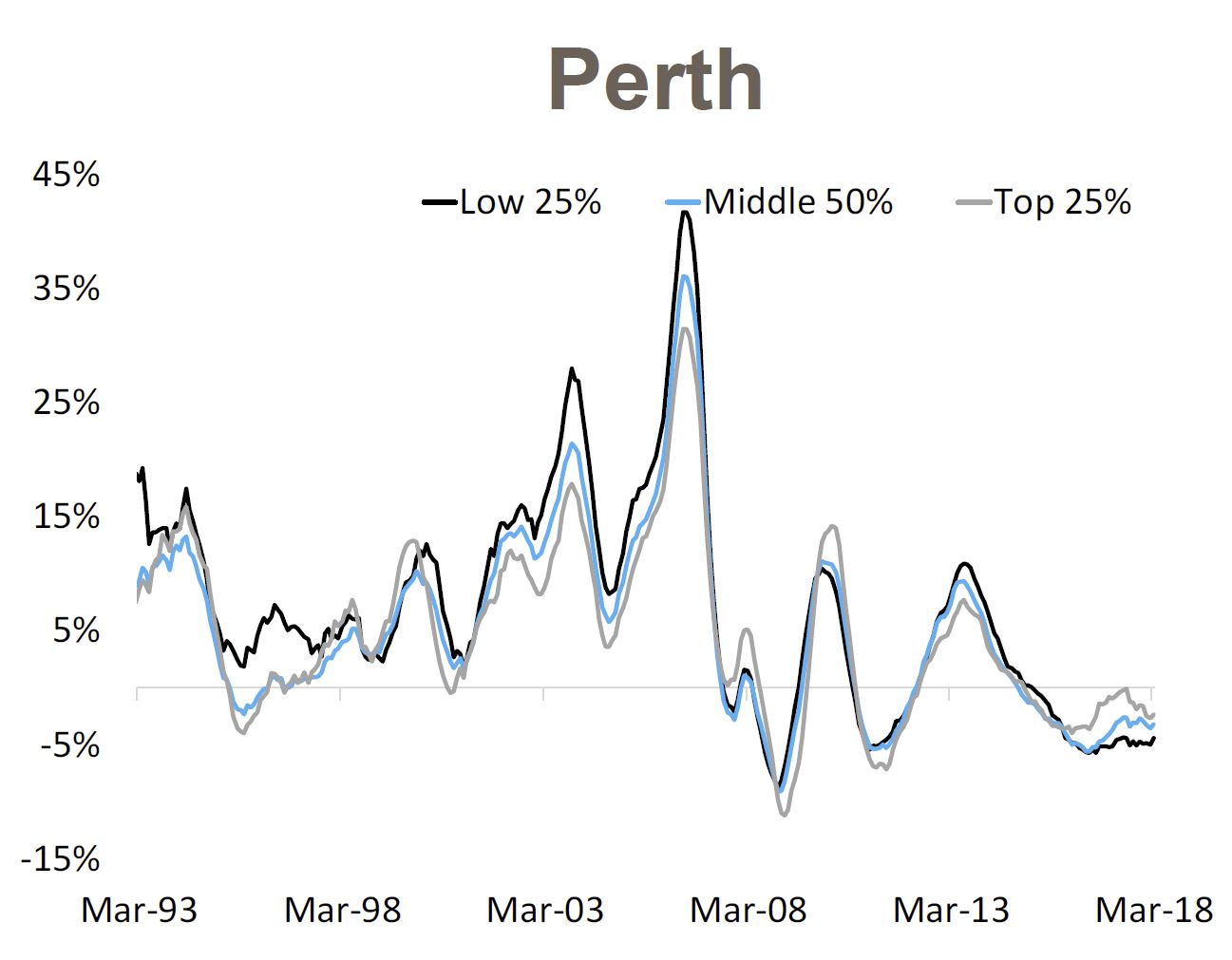

Finally, in Perth values have fallen over the past year across each market sector with the largest declines across the most affordable properties (-4.4%) followed by the middle market (-3.2%) with the most expensive properties recording the most moderate value falls (-2.4%).

Finally, in Perth values have fallen over the past year across each market sector with the largest declines across the most affordable properties (-4.4%) followed by the middle market (-3.2%) with the most expensive properties recording the most moderate value falls (-2.4%).

This shows the importance of granular information, and how misleading overall averages can be.

This shows the importance of granular information, and how misleading overall averages can be.

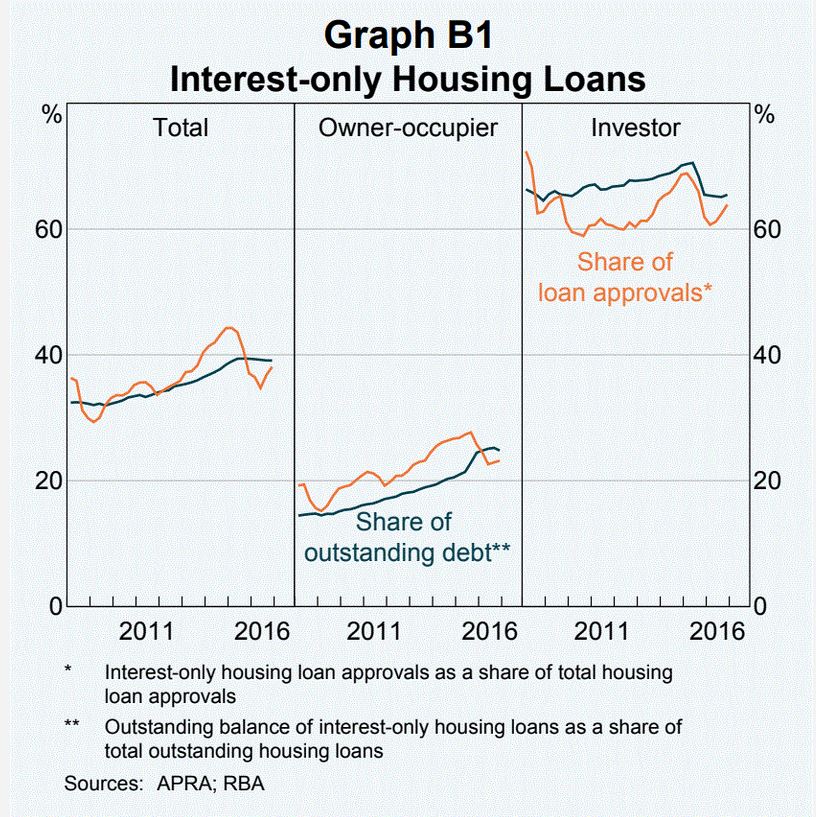

The RBA has released their Financial Stability Review today. It is worth reading the 70 odd pages as it gives a comprehensive picture of the current state of play, though through the Central Bank’s rose-tinted spectacles! They do talk about the risks of high household debt, and warn of the impact of rising interest rates ahead. They home in on the say $480 billion interest only mortgage loans due for reset over the over the next four years, which is around 30 per cent of outstanding loans. Resets to principal and interest will lift repayments by at least 30%. Some borrowers will be forced to sell.

This scenario mirrors the roll over of adjustable rate home loans in the United States which triggered the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis. Perhaps this is our own version! We have previously estimated more than $100 billion in these loans would now fail current tighter underwriting standards.

This scenario mirrors the roll over of adjustable rate home loans in the United States which triggered the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis. Perhaps this is our own version! We have previously estimated more than $100 billion in these loans would now fail current tighter underwriting standards.

I published a more comprehensive review of the Financial Stability Review, and you can watch the video on this report. Importantly the RBA suggests that banks broke the rules in their lending on interest only loans before changes were made to regulation in 2014. The RBA says that there is the potential that these will result in banks having to set aside provisions and/or face penalties for past misconduct or perhaps (more notably) being constrained in the operation of parts of their businesses.

We also did a video on the RBA Chart pack which was released recently. Household consumption is still higher than disposable income, and the gap is being filled by the falling savings ratio. So, we are still spending, but raiding our savings to do so. Which of course is not sustainable. Now the other route to fund consumption is debt, so there should be no surprise to see that total household debt rose again (note this is adjusted thanks to changes in the ABS data relating to superannuation, we have previously breached the 200% mark). But on the same chart we see home prices are now falling – already the biggest fall since the GFC in 2007.

We see all the signs of issues ahead, with household debt still rising, household consumption relying on debt and savings, and overall growth still over reliant on the poor old household sector. We need a proper plan B, where investment is channelled into productive growth investments, not just more housing loans. Yet regulators and government appear to rely on this sector to make the numbers work – but it is, in my view, lipstick on a pig!

Another important report came out from The Bank for International Settlements, the “Central Bankers Banker” has just released an interesting, and concerning report with the catchy title of “Financial spillovers, spillbacks, and the scope for international macroprudential policy coordination“. But in its 53 pages of “dry banker speak” there are some important facts which shows just how much of the global financial system is now interconnected. They start by making the point that over the past three decades, and despite a slowdown coinciding with the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007–09, the degree of international financial integration has increased relentlessly. In fact the rapid pace of financial globalisation over the past decades has also been reflected in an over sixfold increase in the external assets and liabilities of nations as a share of GDP – despite a marked slowdown in the growth of cross-border positions in the immediate aftermath of the GFC. My own take is that we have been sleepwalking into a scenario where large capital flows and international financial players operating cross borders, negating the effectiveness of local macroeconomic measures, to their own ends. This new world is one where large global players end up with more power to influence outcomes than governments. No wonder that they often march in step, in terms of seeking outcomes which benefit the financial system machine. You can watch our separate video discussion on this report. Somewhere along the road, we have lost the plot, but unless radical changes are made, the Genie cannot be put back into the bottle. This should concern us all.

And there was further evidence of the global connections in a piece from From The St. Louis Fed On The Economy Blog which discussed the decoupling of home ownership from home price rises. They say recent evidence indicates that the cost of buying a home has increased relative to renting in several of the world’s largest economies, but the share of people owning homes has decreased. This pattern is occurring even in countries with diverging interest rate policies. And the causes need to be identified. We think the answer is simple: the financialisation of property and the availability of credit at low rates explains the phenomenon.

And finally on the global economy, Vice-President of the Deutsche Bundesbank Prof. Claudia Buch spoke on “Have the main advanced economies become more resilient to real and financial shocks? and makes three telling points. First, favourable economic prospects may lead to an underestimation of risks to financial stability. Second resilience should be assessed against the ability of the financial system to deal with unexpected events. Third there is the risk of a roll back of reforms. The warning is clear, we are not prepared for the unexpected, and as we have been showing, the risks are rising.

Locally more bad bank behaviour surfaced this week. ASIC says it accepted an enforceable undertaking from Commonwealth Financial Planning Limited and BW Financial Advice Limited, both wholly owned subsidiaries of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). ASIC found that CFPL and BWFA failed to provide, or failed to locate evidence regarding the provision of, annual reviews to approximately 31,500 ‘Ongoing Service’ customers in the period from July 2007 to June 2015 (for CFPL) and from November 2010 to June 2015 (for BWFA). They will pay a community benefit payment of $3 million in total. Cheap at half the price!

In similar vein, ASIC says it has accepted an enforceable undertaking from Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) after an investigation found that ANZ had failed to provide documented annual reviews to more than 10,000 ‘Prime Access’ customers in the period from 2006 to 2013. Again, they will pay a community benefit payment of $3 million in total.

Both these cases were where the banks took fees for services they did not deliver – and this once again highlight the cultural issues within the banks, were profit overrides good customer outcomes. We suspect we will hear more about poor cultural norms this coming week as the Royal Commission hearing recommence with a focus on financial planning and wealth management.

Finally to home lending. The ABS released their February 2018 housing finance data. Where possible we track the trend data series, as it irons out some of the bumps along the way. The bottom line is investor as still active but at a slower rate. Some are suggesting there is evidence of stabilisation, but we do not see that in our surveys. Owner occupied loans, especially refinancing is growing quite fast – as lenders seek out lower risk refinance customers with attractive rates. First time buyers remain active, but comprise a small proportion of new loans as the effect of first owner grants pass, and lending standards tighten. You can watch our video on this.

But the final nail in the coffin was the announcement from Westpac of significantly tighten lending standards, with a forensic focus on household expenditure. They have updated their credit policies so borrower expenses will need to be captured at an “itemised and granular level” across 13 different categories and include expenses that will continue after settlement as well as debts with other institutions. They will also be insisting on documentary proof. Moreover, households will be required to certify their income and expenses is true. This cuts to the heart of the liar loans issue, as laid bare in the Royal Commission. That said, Despite the commission raising questions over whether the use of benchmarks is appropriate when assessing the suitability of a loan for a customer, the Westpac Group changes will still apply either the higher of the customer-declared expenses or the Household Expenditure Measure (HEM) for serviceability purposes. You can watch our separate video on this. Almost certainly other banks will follow and tighten their verification processes. This will put more downward pressure on lending multiples, and will lead to a drop in credit, with a follow on to put downward pressure on home prices.

We discussed this in an article which was published under my by-line in the Australian this week, where we argued that excess credit has caused the home price bubble, and as credit is reversed, home prices will fall.

Our central case is for a fall on average of 15-20% by the end of 2019, assuming no major international incidents. The outlook remains firmly on the downside in our view.

The Bank for International Settlements, the “Central Bankers Banker” has just released an interesting, and concerning report with the catchy title of “Financial spillovers, spillbacks, and the scope for international macroprudential policy coordination“.

But in its 53 pages of “dry banker speak” there are some important facts which shows just how much of the global financial system is now interconnected.

They start by making the point that over the past three decades, and despite a slowdown coinciding with the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007–09, the degree of international financial integration has increased relentlessly.

In fact the rapid pace of financial globalisation over the past decades has also been reflected in an over sixfold increase in the external assets and liabilities of nations as a share of GDP – despite a marked slowdown in the growth of cross-border positions in the immediate aftermath of the GFC.

This chart shows the evolution of advanced economies’ financial exposures to a group of large middle-income countries, split into portfolio exposures and bank exposures. It shows that both types of exposures have increased substantially since the late 1990s.

Here is another chart which again the linkages, looking at cross-border liabilities by counterparty. The chart shows the classification of cross-border debt liabilities by type of counterparty. It shows that cross-border liabilities where both creditor and debtor are banks are the largest of the four possible categories, and increased rapidly in the run-up to the GFC. It also shows a rapid increase in credit flows relative to foreign direct investments (FDI) and portfolio equity flows.

They explain that cross-border bank-to-bank funding (liabilities) can be decomposed into two distinctive forms: (a) arm’s length (interbank) funding that takes place between unrelated banks; and (b) related (intragroup) funding that takes place in an internal capital market between global parent banks and their foreign affiliates. They note that cross-border bank-to-bank liabilities have also played a major role in the expansion of domestic lending, at their peak in 2007 these flows accounted for more than 25% of total private credit of the recipient economy.

This also opens the door to potential arbitrage, for example “rebooking” of loans, whereby loans are originated by subsidiaries but then booked on the balance sheet of the parent institution. Indeed, the presence of foreign branches of financial institutions that are not subject to host country regulation may undermine domestic macroprudential policies.

This degree of global linkage raises significant issues, despite the argument trotted about by economists that there are benefits from the improved efficiency of resource allocation.

First, the increased global interconnectedness has led to new risks, associated with the amplification of shocks during turbulent times and the transmission of excess financial volatility through international capital flows. They suggest there is robust evidence that private capital flows have been a major conduit of global financial shocks across countries and have helped fuel domestic credit booms that have often ended in financial crises, especially in developing economies.

Second, international capital flows have created macroeconomic policy challenges for advanced economies as well. For example, the rest of the world’s appetite for US safe assets was an important factor behind the credit and asset price booms in the United States that fuelled the subsequent financial crisis and created turmoil around the world. It is also well documented that since the GFC, the various forms of accommodative monetary policy pursued in the United States and the euro area have exerted significant spillover effects on other countries by influencing interest rates and credit conditions around the world – irrespective, at first sight, of the nature of the exchange rate regime.

Finally, there is evidence to suggest that in recent years financial market volatility in some large middle-income countries has been transmitted back, and to a greater extent, to asset prices in advanced economies and other countries. For instance, the suspension of trading after the Chinese stock market drop on 6 January 2016 affected major asset markets all over the world. Thus, international spillovers have become a two-way street – with the potential to create financial instability in both directions.

This means that macroeconomic settings in the USA – and especially the progressive rise in their benchmark rate, and reversal of QE, will have flow-on effects which will resonate around the global financial system. In a way, no country is an island.

The paper does also make the point that there may be some benefits – for example, if the global economy is experiencing a recession for instance, the coordinated adoption of an expansionary fiscal policy stance by a group of large countries may, through trade and financial spillovers, benefit all countries. The magnitude of this gain may actually increase with the degree to which countries are interconnected, the degree of business cycle synchronisation, and the very magnitude of spillovers.

But, if maintaining financial stability is a key policy objective, the propagation of financial risks through volatile short-term capital flows also becomes a source of concern.

After detailed analysis the paper reaches the following conclusions.

First, with the advance in global financial integration over the last three decades, the transmission of shocks has become a two-way street – from advanced economies to the rest of the world, but also and increasingly from a group of large middle-income countries, which we refer to as SMICs, to the rest of the world, including major advanced economies. These increased spillbacks have strengthened incentives for advanced economies to internalise the impact of their policies on these countries, and the rest of the world in general. Although stronger spillovers and spillbacks are not in and of themselves an argument for greater policy coordination between these economies, the fact that they may exacerbate financial risks – especially when countries are in different phases of their economic and financial cycles – and threaten global financial stability is.

Second, the disconnect between the global scope of financial markets and the national scope of financial regulation has become increasingly apparent, through leakages and cross-border arbitrage – especially through global banks. In fact, what we have learned from the financial trilemma is that it has become increasingly difficult to maintain domestic financial stability without enhancing cross-border macroprudential policy coordination, at least in its structural dimension. Avoiding the leakages stemming from international regulatory arbitrage and open capital markets requires cooperation, but addressing cyclical risks requires coordination.

Third, divergent policies and policy preferences contribute additional dimensions to global financial risks. In the absence of a centralised macroprudential authority, coordination needs to rely on an international macroprudential regime that promotes global welfare. Yet, divergence in national interests can make coordination unfeasible. Fourth, significant gaps remain in the evidence on regulatory spillovers and arbitrage, and the role of the macroprudential regime in the cross-border transmission of shocks. In addition, research on the potential gains associated with multilateral coordination of macroprudential policies remains limited. This may be due in part to the natural or instinctive focus of national authorities on their own country’s objectives, or to greater priority on policy coordination within countries – an important ongoing debate in the context of monetary and macroprudential policies. This “inward” focus may itself be due to the lack of perception of the benefits of multilateralism with respect to achieving national objectives – which therefore makes further research on these benefits all the more important.

This assessment suggests that, in a financially integrated world, international coordination of macroprudential policies may not only be valuable, but also essential, for macroprudential instruments to be effective at the national level. A first step towards coordination has been taken with Basel III’s principle of jurisdictional reciprocity for countercyclical capital buffers, but this principle needs to be extended to a larger array of macroprudential instruments. Further empirical and analytical work (including by the BIS, FSB and IMF) on the benefits of international

macroprudential policy coordination could play a significant role in promoting more awareness of the potential gains associated with global financial stability. This work agenda should involve a research component focused on measuring the gains from coordination and improving data on cross-border financial flows intermediated by various entities (banks, investment funds and large institutional investors), as well as improving capacity for systemic risk monitoring.

My own take is that we have been sleepwalking into a scenario where large capital flows and international financial players operating cross borders, negating the effectiveness of local macroeconomic measures, to their own ends. This new world is one where large global players end up with more power to influence outcomes than governments. No wonder that they often march in step, in terms of seeking outcomes which benefit the financial system machine.

Somewhere along the road, we have lost the plot, but unless radical changes are made, the Genie cannot be put back into the bottle. This should concern us all.

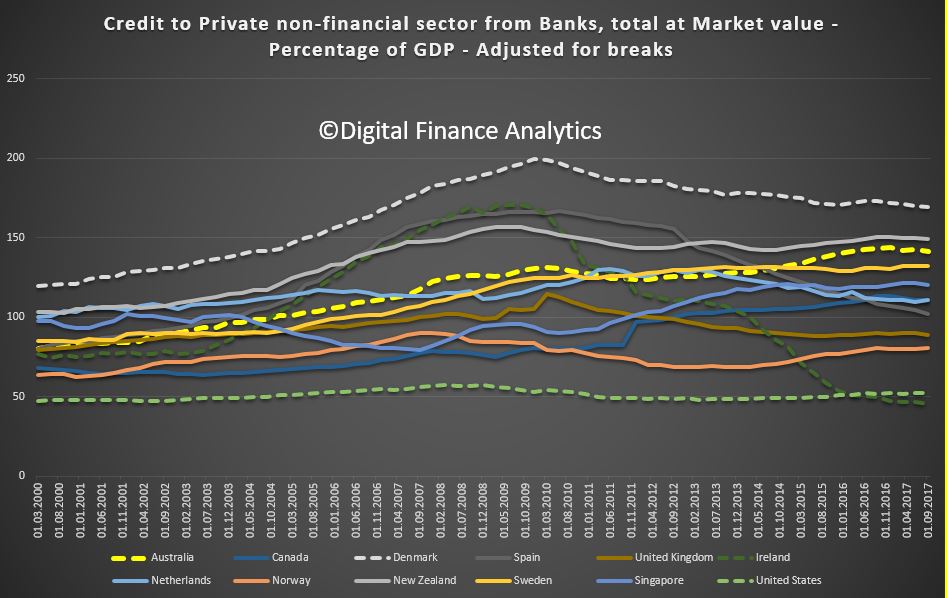

The Bank For International Settlements has released their latest data series of credit to GDP for more than 40 countries. It is a reasonably accurate benchmark.

I have selected some relevant analogues to show that private debt to GDP ratios in Australia remain high, well above USA Canada and UK. Denmark and New Zealand are higher. Australia is the dotted yellow line.

Relevant given my recent post of the impact of credit on Australia!

Relevant given my recent post of the impact of credit on Australia!

You can watch my video blog where we discuss todays releases.

The Bank for International Settlements has just published a special report on Early Warning Indicators Of Banking Crises.

Household and international debt (cross-border or in foreign currency) are a potential source of vulnerabilities that could eventually lead to banking crises. We explore this issue formally by assessing the performance of these debt categories as early warning indicators (EWIs) for systemic banking crises. We find that they do contain useful information. In fact, over the more recent subsample, for household and cross-border debt indicators the information is similar to that of the more commonly used aggregate credit variables regularly monitored by the BIS. Confirming previous work, combining these indicators with property prices improves performance. An analysis of current global conditions based on this richer information set points to the build-up of vulnerabilities in several countries.

Early warning indicators (EWIs) of banking crises are typically based on the notion that crises take root in disruptive financial cycles. The basic intuition is that outsize financial booms can generate the conditions for future banking distress. The narrative of financial booms is well understood: risk appetite is high, asset prices soar and credit surges. Yet it is difficult to detect the build-up of financial booms in real time and with reasonable confidence. It is here that EWIs come in.

Table 4 takes a closer look at the status of the various indicators as of June 2017. Cells are marked in red if the indicator has breached the threshold for predicting at least two thirds of the crises. Those marked in amber correspond to the lower threshold required to predict at least 90% of the crises. This avoids a false sense of precision and captures the very gradual build-up in vulnerabilities. Asterisks indicate that the corresponding combined credit-cum-property price indicator has breached its critical threshold. The picture that emerges is a varied one.

Aggregate credit indicators point to vulnerabilities in several jurisdictions Canada, China and Hong Kong SAR stand out, with both the credit-to-GDP gap and the DSR flashing red. For Canada and Hong Kong, these signals are reinforced by property price developments. The credit-to-GDP gap also flashes red in Switzerland, whereas the total DSR flashes red in Russia and Turkey.

Credit conditions are also quite buoyant elsewhere. Credit-to-GDP gaps and/or the total DSR send amber signals in some advanced economies, such as France, Japan and Switzerland, as well as in several emerging market economies (EMEs). In Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, as well as some other countries, property price gaps underscore this signal.

Some jurisdictions also exhibit some signs of high household sector vulnerabilities. In Korea, Russia and Thailand, the household sector DSR flashes red (Table 4, third column). In Thailand, the red signal for the household DSR is underlined by the property price indicator. Property prices have also been in elevated in Sweden and Canada, which exhibit an amber signal for the household DSR.

The cross-border claims indicator supports the risk assessment for several countries and flags some potential external vulnerabilities for others (Table 4, fourth column). The indicator flashes red for Norway, and is amber for a number of economies.

While providing a general sense of where policymakers may wish to be especially vigilant, these indicators need to be interpreted with considerable caution. As always, they have been calibrated based on past experience, and cannot take account of broader institutional and economic changes that have taken place since previous crises. For example, the much more active use of macroprudential measures should have strengthened the resilience of the financial system to a financial bust, even if it may not have prevented the build-up of the usual signs of vulnerabilities. Similarly, the large increase in foreign currency reserves in several EMEs should help buffer strains. The indicators should be seen not as a definitive warning but only as a first step in a broader analysis – a tool to help guide a more drilled down and granular assessment of financial vulnerabilities. And they may also point to broader macroeconomic vulnerabilities, providing a sense of the potential slowdown in output from financial cycle developments should the outlook deteriorate.

Where do Crypto-curriences fit it? A Central Banker’s view.

Via The Bank For International Settlements. Lecture by Agustín Carstens

General Manager, Bank for International Settlements House of Finance, Goethe University Frankfurt.

One of the reasons that central bank Governors from all over the world gather in Basel every two months is precisely to discuss issues at the front and centre of the policy debate. Following the Great Financial Crisis, many hours have been spent discussing the design and implications of, for example, unconventional monetary policies such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates.

Lately, we have seen a bit of a shift, to issues at the very heart of central banking. This shift is driven by developments at the cutting edge of technology. While it has been bubbling under the surface for years, the meteoric rise of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies has led us to revisit some fundamental questions that touch on the origin and raison d’être for central banks:

The thrust of my lecture will be that, at the end of the day, money is an indispensable social convention backed by an accountable institution within the State that enjoys public trust. Many things have served as money, but experience suggests that something widely accepted, reliably provided and stable in its command over goods and services works best. Experience has also shown that to be credible, money requires institutional backup, which is best provided by a central bank. While central banks’ actions and services will evolve with technological developments, the rise of cryptocurrencies only highlights the important role central banks have played, and continue to play, as stewards of public trust. Private digital tokens posing as currencies, such as bitcoin and other crypto-assets that have mushroomed of late, must not endanger this trust in the fundamental value and nature of money.

The money flower highlights four key properties on the supply side of money: the issuer, the form, the degree of accessibility and the transfer mechanism.

In conclusion, while cryptocurrencies may pretend to be currencies, they fail the basic textbook definitions. Most would agree that they do not function as a unit of account. Their volatile valuations make them unsafe to rely on as a common means of payment and a stable store of value.

They also defy lessons from theory and experiences. Most importantly, given their many fragilities, cryptocurrencies are unlikely to satisfy the requirement of trust to make them sustainable forms of money.

While new technologies have the potential to improve our lives, this is not invariably the case. Thus, central banks must be prepared to intervene if needed. After all, cryptocurrencies piggyback on the institutional infrastructure that serves the wider financial system, gaining a semblance of legitimacy from their links to it. This clearly falls under central banks’ area of responsibility. The buck stops here. But the buck also starts here. Credible money will continue to arise from central bank decisions, taken in the light of day and in the public interest.

In particular, central banks and financial authorities should pay special attention to two aspects. First, to the ties linking cryptocurrencies to real currencies, to ensure that the relationship is not parasitic. And second, to the level playing field principle. This means “same risk, same regulation”. And no exceptions allowed.

The BIS task force has developed five scenarios which highlight how Fintech disruption might play out, in a 50 page report “Implications of fintech developments for banks and bank supervisors.” Bankers will find it uncomfortable reading!

Under the The Bank For International Settlements (BIS) five scenarios, the scope and pace of potential disruption varies significantly, but ALL scenarios show that banks will find it increasingly difficult to maintain their current operating models, given technological change and customer expectations.

Under the The Bank For International Settlements (BIS) five scenarios, the scope and pace of potential disruption varies significantly, but ALL scenarios show that banks will find it increasingly difficult to maintain their current operating models, given technological change and customer expectations.

The fast pace of change in fintech makes assessing the potential impact on banks and their business models challenging. While some market observers estimate that a significant portion of banks’ revenues, especially in retail banking, is at risk over the next 10 years, others claim that banks will be able to absorb or outcompete the new competitors, while improving their own efficiency and capabilities.

The task force used a categorisation of fintech innovations. Graph 1 depicts three product sectors, as well as market support services. The three sectors relate directly to core banking services, while the market support services relate to innovations and new technologies that are not specific to the financial sector but also play a significant role in fintech developments.

The analysis presented in this paper considered several scenarios and assessed their potential future impact on the banking industry. A common theme across the various scenarios is that banks will find it increasingly difficult to maintain their current operating models, given technological change and customer expectations. Industry experts opine that the future of banking will increasingly involve a battle for the customer relationship. To what extent incumbent banks or new fintech entrants will own the customer relationship varies across each scenario. However, the current position of incumbent banks will be challenged in almost every scenario.

1. The better bank: modernisation and digitisation of incumbent players

In this scenario the incumbent banks digitise and modernise themselves to retain the customer relationship and core banking services, leveraging enabling technologies to change their current business models.

Incumbent banks are generally under pressure to simultaneously improve cost efficiency and the customer relationship. However, because of their market knowledge and higher investment capacities, a potential outcome is that incumbent banks get better at providing services and products by adopting new technologies or improving existing ones. Enabling technologies such as cloud computing, big data, AI and DLT are being adopted or actively considered as a means of enhancing banks’ current products, services and operations.

Banks use new technologies to develop value propositions that cannot be effectively provided with their current infrastructure. The same technologies and processes utilised by non-bank innovators can also be implemented by incumbent banks, and examples may include:

- New technologies such as biometry, video, chatbots or AI may help banks to create sophisticated capacities for maintaining a value-added remote customer relationship, while securing transactions and mitigating fraud and AML/CFT risks. Many innovations seek to set up convenient but secure customer identification processes.

- Innovative payment services would also support the better bank scenario. Most banks have already developed branded mobile payments services or leveraged payment services provided by third parties that integrate with bank-operated legacy platforms. Customers may believe that their bank can provide a more secure mobile payments service than do non-bank alternatives.

- Banks may also be prone to offer partially or totally automated robo-advisor services, digital wealth management tools and even add-on services for customers with the intention of maintaining a competitive position in the retail banking market, retaining customers and attracting new ones.

- In this scenario, digitising the lending processes is becoming increasingly important to meet the consumer’s demands regarding speed, convenience and the cost of credit decision-making. Digitisation requires more efficient interfaces, processing tools, integration with legacy systems and document management systems, as well as sophisticated customer identification and fraud prevention tools. These can be achieved by the incumbent by developing its own lending platform, purchasing an existing one, white labelling or outsourcing to third-party service providers. This scenario assumes that current lending platforms will remain niche players.

While there are early signs that incumbents have added investment in digitisation and modernisation to their strategic planning, it remains to be seen to what extent this scenario will be dominant.2. The new bank: replacement of incumbents by challenger banks

In the future, according to the new bank scenario, incumbents cannot survive the wave of technology-enabled disruption and are replaced by new technology-driven banks, such as neo-banks, or banks instituted by bigtech companies, with full service “built-for-digital” banking platforms. The new banks apply advanced technology to provide banking services in a more cost-effective and innovative way. The new players may obtain banking licences under existing regulatory regimes and own the customer relationship, or they may have traditional banking partners.

Neo-banks seek a foothold in the banking sector with a modernised and digitised relationship model, moving away from the branch-centred customer relationship model. Neo-banks are unencumbered by legacy infrastructure and may be able to leverage new technology at a lower cost, more rapidly and in a more modern format.

Elements of this scenario are reflected in the emergence of neo- and challenger banks, such as Atom Bank and Monzo Bank in the United Kingdom, Bunq in the Netherlands, WeBank in China, Simple and Varo Money in the United States, N26 in Germany, Fidor in both the United Kingdom and Germany, and Wanap in Argentina. That said, no evidence has emerged to suggest that the current group of challenger banks has gained enough traction for the new bank scenario to become predominant.

Neo-banks make extensive use of technology in order to offer retail banking services predominantly through a smartphone app and internet-based platform. This may enable the neo-bank to provide banking services at a lower cost than could incumbent banks, which may become relatively less profitable due to their higher costs. Neo-banks target individuals, entrepreneurs and small to medium-sized enterprises. They offer a range of services from current accounts and overdrafts to a more extended range of services, including current, deposit and business accounts, credit cards, financial advice and loans. They leverage scalable infrastructure through cloud providers or API-based systems to better interact through online, mobile and social media-based platforms. The earnings model is predominantly based on fees and, to a lesser extent, on interest income, together with lower operating costs and a different approach to marketing their products, as neo-banks may adopt big data technologies and advanced data analytics. Incumbent banks, on the other hand, may be impeded by the scale and complexity of their current technology and data architecture, determined by factors such as legacy systems, organisational complexity and historical acquisitions. However, the customer acquisitions costs may be high in competitive banking systems and neo-banks’ revenues may be offset by their aggressive pricing strategies and their less-diverse revenue streams.

3. The distributed bank: fragmentation of financial services among specialised fintech firms and incumbent banks

In the distributed bank scenario, financial services become increasingly modularised, but incumbents can carve out enough of a niche to survive. Financial services may be provided by the incumbents or other financial service providers, whether fintech or bigtech, who can “plug and play” on the digital customer interface, which itself may be owned by any of the players in the market. Large numbers of new businesses emerge to provide specialised services without attempting to be universal or integrated retail banks – focusing rather on providing specific (niche) services. These businesses may choose not to compete for ownership of the entire customer relationship. Banks and other players compete to own the customer relationship as well as to provide core banking services.

In the distributed bank scenario, banks and fintech companies operate as joint ventures, partners or other structures where delivery of services is shared across parties. So as to retain the customer, whose expectations in terms of transparency and quality have increased, banks are also more apt to offer products and services from third-party suppliers. Consumers may use multiple financial service providers instead of remaining with a single financial partner.

Elements of this scenario are playing out, as evidenced by the increasing use of open APIs in some markets. Other examples that point towards the relevance of this scenario are:

- Lending platforms partner and share with banks the marketing of credit products, as well as the approval process, funding and compliance management. Lending platforms might also acquire licences, allowing them to do business without the need to cooperate with banks.

- Innovative payment services are emerging with joint ventures between banks and fintech firms offering innovative payment services. Consortiums supported by banks are currently seeking to establish mobile payments solutions as well as business cases based on DLT for enhancing transfer processes between participating banks (see Box 4 for details of mobile wallets).

- Robo-advisor or automated investment advisory services are provided by fintech firms through a bank or as part of a joint venture with a bank.

Innovative payment services are one of the most prominent and widespread fintech developments across regions. Payments processing is a fundamental banking operation with many different operational models and players. These models and structures have evolved over time, and recent advances in technological capabilities, such as in the area of instant payment, have accelerated this evolution. Differences in types of model, technology employed, product feature and regulatory frameworks in different jurisdictions pose different risks.

The adoption by consumers and banks of mobile wallets developed by third–party technology companies – for example, Apple Pay, Samsung Pay,12 and Android Pay – is an example of the distributed bank scenario. Whereas some banks have developed mobile wallets in-house, others offer third-party wallets, given widespread customer adoption of these formats. While the bank continues to own the financial element of the customer relationship, it cedes control over the digital wallet experience and, in some cases, must share a portion of the transaction revenue facilitated through the third-party wallets.

Innovation in payment services has resulted in both opportunities and challenges for financial institutions. Many of the technologies allow incumbents to offer new products, gain new revenue streams and improve efficiencies. These technologies also let non-bank firms compete with banks in payments markets, especially in regions where such services are open to non-bank players (eg the Payment Service Directives in the European Union and the Payment Schemes or Payment Institutions Regulation in Brazil).

4. The relegated bank: incumbent banks become commoditised service providers and customer relationships are owned by new intermediaries

In the relegated bank scenario, incumbent banks become commoditised service providers and cede the direct customer relationship to other financial services providers, such as fintech and bigtech companies. The fintech and bigtech companies use front-end customer platforms to offer a variety of financial services from a diverse group of providers. They use incumbent banks for their banking licences to provide core commoditised banking services such as lending, deposit-taking and other banking activities. The relegated bank may or may not keep the balance sheet risk of these activities, depending on the contractual relationship with the fintech company.

In the relegated bank scenario, big data, cloud computing and AI are fully exploited through various configurations by front-end platforms that make innovative and extensive use of connectivity and data to improve the customer experience. The operators of such platforms have more scope to compete directly with banks for ownership of the customer relationship. For example, many data aggregators allow customers to manage diverse financial accounts on a single platform. In many jurisdictions consumers become increasingly comfortable with aggregators as the customer interface. Banks are relegated to being providers of commoditised functions such as operational processes and risk management, as service providers to the platforms that manage customer relationships.

Although the relegated bank scenario may seem unlikely at first, below are some examples of a modularised financial services industry where banks are relegated to providing only specific services to another player who owns the customer relationship:

- Growth of payment platforms has resulted in banks providing back office operations support in such areas as treasury and compliance functions. Fintech firms will directly engage with the customer and manage the product relationship. However, the licensed bank would still need to authenticate the customer to access funds from enrolled payment cards and accounts.

- Online lending platforms become the public-facing financial service provider and may extend the range of services provided beyond lending to become a new intermediary between customers and banks/funds/other financial institutions to intermediate all types of banking service (marketplace of financial services). Such lending platforms would organise the competition between financial institutions (bid solicitations) and protect the interests of consumers (eg by offering quality products at the lowest price). Incumbent banks would exist only to provide the operational and funding mechanisms.

- Banks become just one of many financial vehicles to which the robo-advisor directs customer investments and financial needs.

- Social media such as the instant messaging application WeChat13 in China leverage customer data to offer its customers tailored financial products and services from third parties, including banks. The Tencent group has launched WeBank, a licensed banking platform linked to the messaging application WeChat, to offer the products and services of third parties. WeBank/WeChat focuses on the customer relationship and exploits its data innovatively, while third parties such as banks are relegated to product and risk management.

5. The disintermediated bank: Banks have become irrelevant as customers interact directly with individual financial services providers.

Incumbent banks are no longer a significant player in the disintermediated bank scenario, because the need for balance sheet intermediation or for a trusted third party is removed. Banks are displaced from customer financial transactions by more agile platforms and technologies, which ensure a direct matching of final consumers depending on their financial needs (borrowing, making a payment, raising capital etc).

In this scenario, customers may have a more direct say in choosing the services and the provider, rather than sourcing such services via an intermediary bank. However, they also may assume more direct responsibility in transactions, increasing the risks they are exposed to. In the realm of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending for instance, the individual customers could be deemed to be the lenders (who potentially take on credit risk) and the borrowers (who may face increased conduct risk from potentially unregulated lenders and may lack financial advice or support in case of financial distress).

At the moment, this scenario seems far-fetched, but some limited examples of elements of the disintermediation scenario are already visible:

- P2P lending platforms could manage to attract a significant number of potential retail investors so as to address all funding needs of selected credit requests. P2P lending platforms have recourse to innovative credit scoring and approval processes, which are trusted by retail investors. That said, at present, the market share of P2P lenders is small in most jurisdictions. Additionally, it is worth noting that, in many jurisdictions, P2P lending platforms have switched to, or have incorporated elements of, a more diversified marketplace lending platform business model, which relies more on the funding provided by institutional investors (including banks) and funds than on retail investors.

- Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, effect value transfer and payments without the involvement of incumbent banks, using public DLT. But their widespread adoption for general transactional purposes has been constrained by a variety of factors, including price volatility, transaction anonymity – raising AML/CFT issues – and lack of scalability.

In practice the report highlights that a blend of scenarios is most likely.

The scenarios presented are extremes and there will likely be degrees of realisation and blends of different scenarios across business lines. Future evolutions may likely be a combination of the different scenarios with both fintech companies and banks owning aspects of the customer relationship while at the same time providing modular financial services for back office operations.

For example, Lending Club, a publicly traded US marketplace lending company, arguably exhibits elements of three of the five banking scenarios described. An incumbent bank that uses a “private label” solution based on Lending Club’s platform to originate and price consumer loans for its own balance sheet could be characterised as a “distributed bank”, in that the incumbent continues to own the customer relationship but shares the process and revenues with Lending Club.

Lending Club also matches some consumer loans with retail or institutional investors via a relationship with a regulated bank that does not own the customer relationship and is included in the transaction to facilitate the loan. In these transactions, the bank’s role can be described as a “relegated bank” scenario. Other marketplace lenders reflect the “disintermediated” bank scenario by facilitating direct P2P lending without the involvement of a bank at any stage.

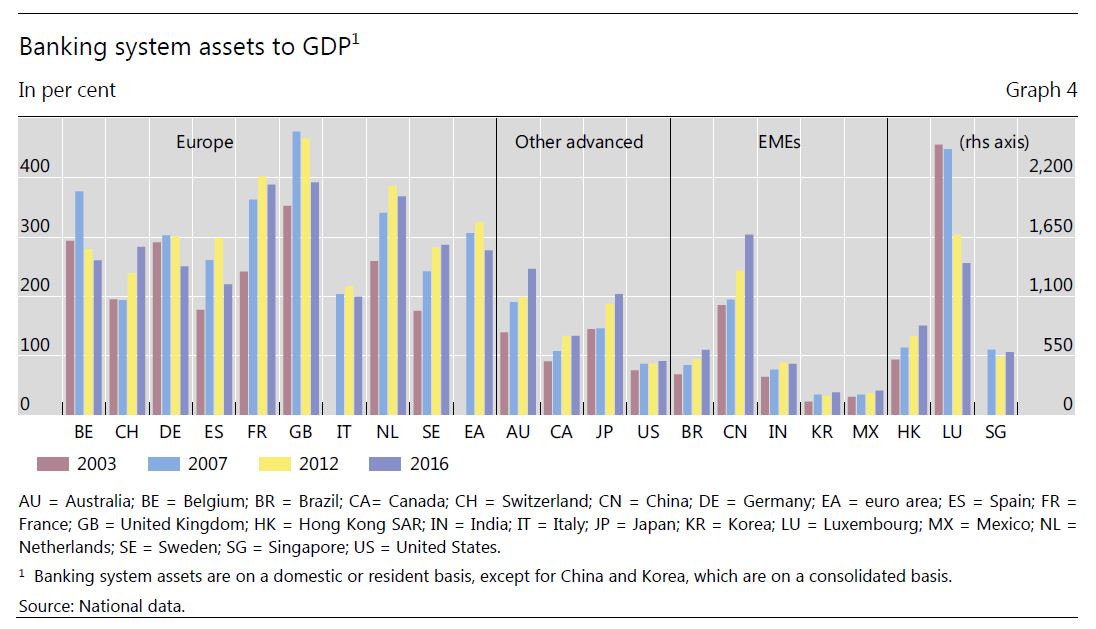

The Committee on the Global Financial System at The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has published an important report “Structural changes in banking after the crisis“.

The report highlights a “new normal” world of lower bank profitability, and warns that banks may be tempted to take more risks, and leverage harder in an attempt to bolster profitability. This however, should be resisted. They also underscore the issues of banking concentration and the asset growth, two issues which are highly relevant to Australia.

The report highlights that in some countries the 2007 banking crisis brought about the end of a period of fast and excessive growth in domestic banking sectors. Worth noting the substantial growth in Australia, relative to some other markets and of particular note has been the dramatic expansion of the Chinese banking system, which grew from about 230% to 310% of GDP over 2010–16 to become the largest in the world, accounting for 27% of aggregate bank assets.

They also call out the concentration banking to a smaller number of larger players since the crisis. The number of banks has fallen in most countries

They also call out the concentration banking to a smaller number of larger players since the crisis. The number of banks has fallen in most countries

over the past decade. Post-crisis reductions in bank numbers have been mainly among smaller institutions, aside from a handful of distressed large banks in the euro area and the retreat of some international banks from specific foreign markets. Concentration has also risen in some countries that were less affected by the crisis and where bank numbers have

continued to expand or remained steady (Australia, Brazil, Singapore).

The decade since the onset of the global financial crisis has brought about significant structural changes in the banking sector. The crisis revealed substantial weaknesses in the banking system and the prudential framework, leading to excessive lending and risk-taking unsupported by adequate capital and liquidity buffers. The effects of the crisis have weighed heavily on economic growth, financial stability and bank performance in many jurisdictions, although the headwinds have begun to subside. Technological change, increased non-bank competition and shifts in globalisation are still broader environmental challenges facing the banking system.

Regulators have responded to the crisis by reforming the global prudential framework and enhancing supervision. The key goals of these reforms have been to increase banks’ resilience through stronger capital and liquidity buffers, and reduce implicit public subsidies and the impact of bank failures on the economy and taxpayers through enhanced recovery and resolution regimes. At the same time, the dynamic adaptation of the system and the emergence of new risks warrant ongoing attention.

In adapting to their new operating landscape, banks have been re-assessing and adjusting their business strategies and models, including their balance sheet structure, cost base, scope of activities and geographic presence. Some changes have been substantial and are ongoing, while a number of advanced economy banking systems are also confronted with low profitability and legacy problems.

This report by the CGFS Working Group examines trends in bank business models, performance and market structure, and assesses their implications for the stability and efficiency of banking markets.

The main findings on the evolution of banking sectors are as follows:

The main findings regarding the impact of post-crisis structural change for the stability of the banking sector are related to three areas:

Changes in banking sector resilience have to be measured against the impact on the services provided by the sector. The main findings regarding the impact of changes on the efficiency of financial intermediation services are:

The report highlights four key messages for markets and policymakers: